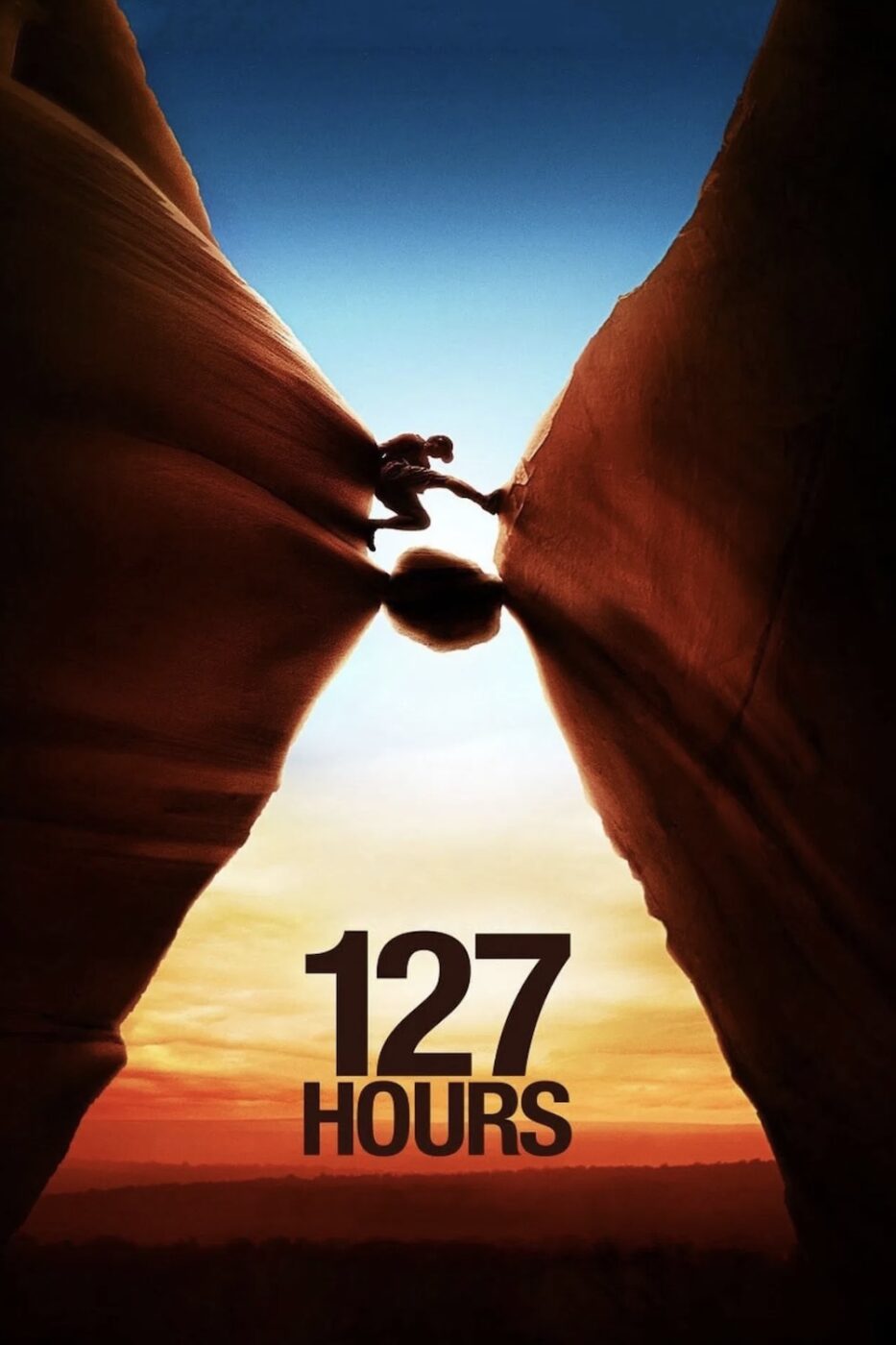

127 HOURS (2010)

A mountain climber becomes trapped under a boulder while canyoneering alone near Moab, Utah and resorts to desperate measures in order to survive.

A mountain climber becomes trapped under a boulder while canyoneering alone near Moab, Utah and resorts to desperate measures in order to survive.

When you think of the most successful British film directors working today, Danny Boyle has to be considered worthy enough to be grouped together with other such legendary names like Ridley Scott or Christopher Nolan. His first film, Shallow Grave (1994), seemed to come out of nowhere, quickly garnering strong reviews and reasonable commercial success. Less than two years later, Trainspotting (1996) went on to be a massive hit. In the UK, thanks to author Irvine Welsh’s already popular novel, and with the help of its Britpop-heavy soundtrack and iconic poster, it soon became something of a cultural phenomenon and earned a whopping $72M around the world, against a paltry £1.5M budget.

Apart from those titles, The Beach (2000), 28 Days Later (2002), and Slumdog Millionaire (2008) are probably Boyle’s most recognisable—and biggest—films to date, but all of his filmography (with the exception of 1997’s A Life Less Ordinary) remains very strong, right up to this year’s 28 Years Later. And while all these are, for the most part, superbly made, it was Boyle’s follow-up to Slumdog that I think remains one of his most interesting and thought-provoking creations. That film is 127 Hours.

Based on outdoorsman and adventurer Aron Ralston’s 2004 book Between a Rock and a Hard Place, this amazing tale of survival details the somewhat unfortunate events of Ralston himself, who, in 2003, while out on his own exploring Utah’s isolated Blue John Canyon, fell and trapped his arm under a boulder. In just a few seconds, Ralston’s world literally came crashing around him, and with it, his life was changed forever. The only items he had on him that could keep him breathing were 350ml of water and a few snacks. He also had a video camera and some climbing equipment, but we’ll get to all that in a second…

As the hours and days slide away, the once cocky 27-year-old starts to lose his grip on reality; with this, he starts experiencing hallucinations, some of which include loved ones he’s pushed away over the years because of his selfishness. Finally, Ralston reaches the conclusion that his only way out of the canyon alive means doing something that most people would deem unthinkable: he would have to amputate his own arm. So, equipped with just a make-shift tourniquet and a blunt multi-tool blade, he finally cuts part of his limb off and manages to escape, eventually getting rescued by a family out on a hike several hours later.

Fairly soon after Ralston’s biographical book had been published in 2004, Boyle had read it and was immediately taken with the story. Together with screenwriter Simon Beaufoy (The Full Monty), they set about writing a treatment for the film; the Lancashire-born filmmaker’s ambition was to make “an action movie with a guy who can’t move”. As the days drag on, loneliness and his sanity become just as challenging as the physical pain. That emotional journey is what really hooked Boyle and his screenwriter. Along with this captivating account, the other main motivation behind the project was that, after making Slumdog, Boyle was eager to make something far more intimate in scale. Talking about its genesis, Boyle said: “I remember thinking, I must do a film where I follow an actor the way Darren Aronofsky did with The Wrestler (2008). So 127 Hours is my version of that.”

Before becoming a film director, Boyle cut his teeth in the world of theatre and television. After he graduated from Bangor University, he found work at London’s Royal Court Theatre where he directed five productions for the Royal Shakespeare Company. Then, in 1987, he went over to BBC Ireland in a producing role, working on Alan Clarke’s film Elephant, a story set around the Troubles, after which he got into the director’s chair for several one-off series, as well as directing a couple of episodes of ITV’s hugely popular Inspector Morse.

Looking at this early stage of his career, you can see parallels that sit well against his films: Boyle is incredibly adept at working with very different genres, and he always doubles down on story and characters. This is why he remains one of Britain’s most prominent figures in the arts. Aside from his versatility, Boyle’s creative output is hugely prolific; he even managed to find time between making features to direct an all-star 2011 theatre production of Frankenstein, starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller in alternate main roles on different nights. And after that huge success, Boyle directed the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics.

Going back to Ralston’s story, the main plot point of someone surviving a seemingly insurmountable challenge can also explain Boyle’s interest behind his involvement—he even said in an interview that throughout his diverse back catalogue, the one theme that remains is that “they’re all about someone facing impossible odds and overcoming them.” While this is certainly true, I think another factor that’s always part of a Danny Boyle film is just how kinetic they all are. 127 Hours is no exception.

Whereas some lesser filmmakers may have struggled to create a visually arresting and dynamic film about one man trapped in a single location, this obviously proved to be no problem for Boyle’s usual inventive genius as the finished film doesn’t let up from frame one. The opening intro set against the thumping track Never Hear Surf Music Again by Free Blood is a multi-screen combo of sped-up films showing human activity en masse: workers commuting; traders on Wall Street; pilgrims in Mecca; various sporting events. However, amongst all this montage of humanity, we then observe a screen showing a solitary figure going about his flat as he’s getting ready for some excursion—it is, of course, our protagonist Aron Ralston (James Franco).

This opener of slickly edited footage against a catchy soundtrack pretty much lays the creative template for the entire movie. Trippy dream sequences, time-lapse shots; the visuals constantly reflect the character’s mental state. The music by Indian composer A.R Rahman (Slumdog Millionaire) does a similar job: mixing an eclectic soundscape of ambient sound and pulsing rhythms that all go to deliver an emotionally driven score. The overall sound design has to be credited too; when watching, you really can imagine what it must have been like for Ralston over the course of those five lonely days in the desert: gravel crunching, a raven flying overhead, torrential rain—all are perfectly created to great effect.

In what is quite a rare decision, Boyle employed two separate cinematographers, Anthony Dod Mantle and Enrique Chediak; both filmed 50% each—this enabled Boyle and Franco to push through the long days without wearing out the crew, thus allowing for the overall shoot to be completed in a relatively short nine weeks. Mantle and Chediak’s techniques of hand-held camera footage and close-ups help keep things to look aesthetically fresh, in certain sequences giving an almost documentary texture to the film.

While the movie used some of the real Utah locations that Ralston had travelled across, the production crew decided it was too impractical and dangerous to place cameras and people inside the actual accident site for filming. Instead, designers built a set in a warehouse made of silicone and fibreglass, matching the ridges and angles of the real rock. Such is the high quality of artistry on display, it’s no exaggeration to say the whole setting looks like you’re actually there. And, of course, alongside all of this first-rate technical work, actor James Franco’s career-best performance also goes some way in convincing you that what you’re watching is real.

Up to the point of 127 Hours getting made, Franco had made a name for himself as a dependable performer with some talent. He’d consistently worked since the early 2000s, and thanks to his looks, had even played James Dean in a TV movie back in 2001. Robert De Niro had spotted him here and helped Franco get the part of a homeless drug addict in crime drama City by the Sea (2002). After this, Franco started getting bigger supporting parts, most notably as Peter Parker’s friend Harry Osborne in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man trilogy, and playing a friendly drug dealer in the smash stoner comedy, Pineapple Express (2008). But despite this relative success, Franco had never carried a film solely by himself, so Boyle and the studio were making a big risk by casting him in this intense and difficult role.

Thankfully, for all concerned, Franco wasn’t just good in the lead part, his acting throughout is excellent. Right from the off, the actor manages to bring across a complete sense of authenticity in everything he does, and most of these points are seemingly mundane: things like how he packs his rucksack, the way he rides his bike, his casual, carefree style of walking—immediately, you see someone who’s clearly athletic, confident with being outdoors and managing the terrain skilfully, and is just a friendly, laidback kind of guy. And then there’s the not-so-nice part of the role.

During the scenes when Ralston is trapped in the canyon, Boyle encouraged Franco to improvise extensively. Because of the tight environment and the story’s focus, the filmmakers relied on extended, continuous shots—some running over 20 minutes—in which Franco was encouraged to go all out and fully inhabit each moment, often improvising alongside the camera operator. Franco later explained that he gained valuable experience from this approach, crediting Boyle’s experimental, collaborative style for helping him deliver a more genuine performance. While much of the dialogue, including Aron Ralston’s recorded video diary entries, was informed by real footage, the actor was still given considerable room to be spontaneous. Boyle intentionally chose this method to inject the film with a sense of urgency and movement, ensuring it didn’t feel stagnant despite its largely confined setting.

For the amputation scene, Boyle hired make-up designer Tony Gardner and effects company Alterian, Inc. to realistically depict the character’s self-amputation, believing the accuracy of the arm and the procedure was essential to the film’s impact. The team built layered prosthetic arm rigs with bones, muscle, veins, and translucent silicone skin, creating three versions—two showing the interior and one the exterior. Gardner described the process as highly stressful and credited James Franco for helping sell the effect.

To add an extra layer of legitimacy to the proceedings, Ralston served as a key consultant, guiding the filmmakers through each step of his ordeal and sharing footage he recorded while trapped. The completed scene is obviously hard to watch, but the filmmakers’ attention to detail isn’t there to merely cause disgust or shock, it’s key to Ralston’s incredible story, so to show something that looked fake wouldn’t only undermine the entire film, but also be a huge disservice to Ralston’s amazing ordeal.

The film’s release was met with huge critical acclaim, and Franco picked up nominations for an Academy Award, Golden Globe and SAG award, as well as winning an Independent Spirit Award. Richard Roeper of The Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four stars and said the film was “one of the best of the decade”. Roger Ebert also awarded the film four stars out of four and wrote that “127 Hours is like an exercise in conquering the unfilmable”. Commercially, it didn’t earn huge amounts at the box office, but it cleared $60.7M against an $18M budget.

I first saw the film back in 2011 at the cinema, and found it to be an immensely moving viewing experience. Rewatching it for this feature, it’s safe to say the movie has lost none of its power. And while you can’t ignore Franco’s recent problematic behaviour of late, his skilled performance here is undeniably brilliant. Without his dedication to what must have been a hugely difficult role, 127 Hours would have possibly misfired horrendously; instead, what you’re left with is one of the most memorable survival films ever made.

Standout scenes (my top two, anyway) that linger in the memory: the swooping camera that somehow flies out of the canyon as Ralston futilely screams to get someone’s attention—and you realise he really is in the middle of nowhere—and when he’s interviewing/reproaching himself on camera, pretending to be on the “Morning Show in canyon land”; watching this play out is both hilarious and sad as it’s here that he truly understands how much of a selfish idiot he’s been over the years, and more pressingly, that he made the monumental mistake of not telling anyone where he was going that weekend.

But apart from Boyle’s energetic direction, the strong script and Franco’s committed acting, the “secret sauce” here that makes it special is that it’s not just about someone surviving against the odds, it’s a reminder of how fragile and precious our lives are. Ralston finally realised this at some point over those five agonising days, and seeing this emotional core of the story told so effectively all adds an extra layer of quality and brings everything together to create something that’s intense, weirdly uplifting, and unforgettable.

UK • USA • FRANCE | 2010 | 94 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • ITALIAN

director: Danny Boyle.

writers: Danny Boyle & Simon Beaufoy (based on the book ‘Between A Rock and a Hard Place’ by Aron Ralston)

starring: James Franco, Amber Tamblyn, Kate Mara, Clémence Poésy, Lizzy Caplan, Kate Burton, Treat Williams & Pieter Jan Brugge.