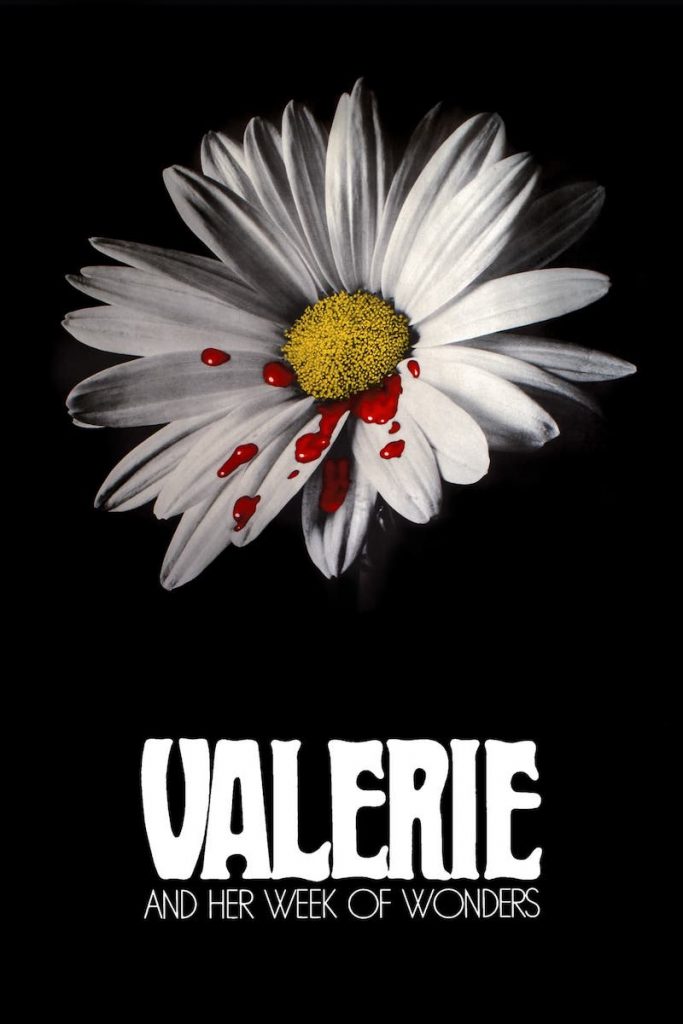

VALERIE AND HER WEEK OF WONDERS (1970)

A surreal tale in which love, fear, sex and religion merge into one fantastic world.

A surreal tale in which love, fear, sex and religion merge into one fantastic world.

Valerie and her Week of Wonders opens with a beautifully perplexing soft-focus montage involving a pretty young girl. We’re inundated with symbols of innocence: the light is golden, daisies abound, pure clear water splashes and sparkles. The girl lays back in the grass and holds a white dove to her lips… she kneels in prayer and makes eye contact with the viewer… she even pops an under-ripe cherry into her mouth.

There’s an uneasy feeling that this could take us into decidedly dodgy David Hamilton territory. But Luboš Fišer’s naïve score of harpsichords with choral accompaniment also brings to mind flashbacks of some psycho’s childhood trauma in a Dario Argento thriller. If this is a first viewing, whatever expectations these established stereotypes exploit are almost certainly about to be challenged, just as the girl challenges your gaze during the opening titles…

This is, or at least was, a unique movie that straddles the borders between arthouse, exploitation, coming-of-age melodrama, fantasy, and horror. It even puts forward a case to be approached as a comedy and is certainly heavy on satire.

The most glaring of its few flaws would be that it tries to be too many things at once and, while it does all these well, it would’ve been stronger had it settled on which approach should dominate. Instead, it develops a dialogue between different cinematic styles and narrative approaches, keeping things engrossing yet confusing throughout.

There’s a proper story concealed in the midst of its relentlessly gorgeous imagery, but sometimes it feels like waking from a long and involved dream and struggling to reconcile it with reality. Perhaps it’s better not to try but simply surrender to the marvellous milieu. Sit back and let the cinematography of Jan Curík work its painterly spell.

Valerie (Jaroslava Schallerová) is dozing in a glasshouse when a young man drops in through a skylight and steals her pearl earrings. She wakes in time to see him leap lightly from the glass roof. Seemingly undaunted by the darkness beyond, Valerie lights a lamp and ventures barefoot in pursuit, not unlike Alice following the White Rabbit.

She passes a disturbed beehive, carved from wood into a statue of Adam and Eve, and witnesses a polecat killing a hen. She then sees the young man again, stealing chickens from the barn with the aid of a frightening accomplice in a black cape and with a scary, deathly-white face. By eavesdropping from the shrubbery, she learns that the young man’s name is Orlik / Eaglet (Petr Kopriva) and his vampiric master is called Tchor / Polecat (Jirí Prýmek).

None of this seems to phase Valerie and we gradually come to the realisation she’s still dreaming. She pauses to pick a daisy she just stepped over and admires the beads of blood on its white petals that sparkle like gemstones.

If one wants to make sense of the story, at least in a rational way, then it would be best to consult a dictionary of symbols, an outline of Propp’s Morphology of the folk tale, and a summary of Jungian archetype theory. Like many works of surrealism, it seems that Valerie is a result of throwing all these ingredients into a big cauldron and stirring well!

When Valerie does awaken, she finds herself in a world of folktale tropes. Her pallid, decidedly Goth, grandmother (Helena Anýzová) mysteriously appears from an alcove alongside an ostentatious ceramic stove. When Valerie expresses excitement that “the actors have arrived,” Grandma admonishes her, saying she should be more interested in the missionaries that are also coming.

Valerie’s pearl earrings become a central motif as it turns out they’re a family heirloom, left to Valerie when her mother abandoned her to join a convent. Valerie learns that she was born out of wedlock and her mother never let-on who the father was, though it’s rumoured he was a bishop.

The earrings, though, were a acquired from ‘The Constable’ (Jirí Prýmek again) who had an affair with the grandmother, who might not be quite what she appears… And so, we’re immersed in a multi-generational family saga of mysteries and intrigue. Certainly, a few of the dysfunctional ‘Gothic family’ boxes have just been ticked! But don’t think that’ll make things predictable.

As Valerie watches the procession of minstrels and players arrive in town, she spots Orlik, the young man from her dream, among them, also briefly glimpsing the frightening, reaper-like Tchor once more. Orlik returns her pearl earrings, now imbued with magical protective powers, and begins to woo her with letters delivered by dove. He hints that the Constable is a vampire, intent on taking possession of her family homestead… and her.

I had great fun discussing, dissecting, and deciphering this multi-layered narrative. From the start, it’s apparent that everything about the film is at once both surface and symbol. As symbolism is culturally dependent, I’m not going to spoil things by sharing my theories here, besides it’s all part of the richly rewarding viewer experience that keeps Valerie and Her Week of Wonders perennially watchable.

Though the film certainly embraces Surrealist ideologies, it’s not that simple to pigeonhole. The script is loosely adapted from the Gothic novel Valerie a Týden Divů, written in 1935 and circulated in manuscript form for a decade before its publication in 1945. Its author, Vítězslav Nezval, was a prominent figure in the prolific Prague literary scene of the early-20th-century. During the 1920s, he was a member of Devětsil, an insular yet influential group of avant-garde artists and Marxist intellectuals who saw the arts as a force for change in the newly formed First Czechoslovak Republic.

In 1924, Nezval was also a founder member of the Prague Poetist movement which endeavoured to imbue everyday objects and events with beauty and wonder. These ideas aligned with those of his friend, André Breton, the French poet who wrote the Surrealist Manifesto the same year. Surrealism and Poetism grew alongside each other and when Nezval helped establish the Surrealist Group of Czechoslovakia in 1934, their ideologies had merged.

I’m pretty sure it benefitted from a woman’s touch when Ester Krumbachová adapted the novel with the initial intention of her husband, Jan Němec, co-directing. They were both notable filmmakers of the Czech New Wave, earning notoriety for their politically charged satires. She’d previously penned A Report on the Party and the Guests / O Slavnosti a Hostech (1966), adapted from her own novella and directed by Němec. That film would result in them both having their state approval revoked when the revolutionary reforms of early 1968 were suppressed by the Soviet Invasion, later the same year.

By the time Valerie and Her Week of Wonders began production, the Barrandov Studios had already fired Němec, replacing him with fellow Czech New Wave heavy-weight Jaromil Jireš, often cited as initiating the movement with The Cry / Křik (1964). It’s rather poetic, then, that he should get to direct the last film of the Czech New Wave, just six years later, marking the end of an era.

Krumbachová was kept on as production designer and collaborated with Jireš on the final screenplay. They subtly disguised any political themes within an allegorical coming-of-age drama. Parallels are drawn between the optimistic vibe of the early, interwar period when the story was originally written, and the radical reforms taking place around them that had culminated in the brief push for sociopolitical liberty known as The Prague Spring. Valerie was made in this brief window of opportunity before a new totalitarian regime was enforced by the invading Soviet powers.

Understanding the context of the film’s production provides an alternative reading for the entire dreamy narrative. By 1970, stringent state censorship had put a definitive end to the nation’s artistic freedom for the next 20 years.

Apart from pushing the vampire thread to the fore, the most notable and controversial change made by Jireš and Krumbachová was to alter the age of Valerie from 17, as in the novel, to 13. Biologically speaking, this did make more sense as the narrative’s inciting incident is the onset of puberty, and the archetypal motif of her first period. It also increased the sense of threat and of vulnerability. Not to mention making the casting process problematic. Apparently, more than 1,500 girls auditioned for the part.

The few sequences involving sexualised imagery of a pubescent child, including partial nudity, is a disturbing element that will provoke mixed feelings. My protective, fatherly instinct kicked in and I was concerned for the wellbeing of Valerie and hoped that nothing bad happened to the vulnerable child actress.

Recent interviews with Jaroslava Schallerová allay those fears. She says she enjoyed the whole filming experience, describing it as being like a special summer holiday. It was also when she first met Petr Porada, who turned out to be her future husband. So, it’s with great fondness that she recalls the filming.

When recounting the witch-burning scene, she admits that some aspects of health and safety weren’t taken as seriously as they would be today! That was the most dangerous part of the entire shoot. Despite her hair frizzing with the heat, she still felt safe. Apparently, her mother, who was present at all times, needed a stiff drink after that scene was successfully in the can.

Schallerová was clearly the right choice for the part as she manages to deliver an open, honest and intricately nuanced performance. There’s no denying she’s beautiful and Valerie may trigger memories of how it felt to be that same age. The way the camera lingers on her little mannerisms taps into memories of that magical time when you first start having genuinely gendered feelings. Possibly, that one fleeting summer when young love is filled with wonderfully confusing emotions. Unrealistically interpreted through the lens of childhood fictions, poetry, pop songs and fairy tales. A beautiful idea, before it becomes complicated with the adult aspects of ‘serious’ relationships.

Surely, as a teenager, I would’ve been besotted, lacking the emotional dexterity to handle overwhelming new feelings. I think it’s what people used to refer to as ‘that awkward age’, and some are fortunate enough to experience a unique mix of euphoria and fear, resulting in shy wonder. This film beautifully captures that transient innocence.

Few films come to mind that deal with such themes so successfully and poetically. Perhaps Gavin Miller’s film of Dennis Potter’s Dreamchild (1986), which owes much to Valerie in its blend of memories, dream, and reality. Certainly, it riffs on that same Alice in Wonderland exploration of sexual awakening. Vincent Ward’s equally poetic Vigil (1984) maps-out similar thematic territory, in a vastly different landscape. Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976) also tackles the same subtexts, but does so with a much brasher and blunt approach!

Another film known to be directly inspired by Valerie is Neil Jordan’s The Company of Wolves (1984). It’s pretty much a remake, only with werewolves instead of vampires. Angela Carter wrote the original short story after going to a rare BFI screening of Valerie and Her Week of Wonders. The resulting movie, that she co-wrote with Jordan, lacks any of the delicacy and poetic beauty of Valerie. As would be expected, it turned out as a more literal and contrived reworking of familiar folklore, adding nothing except its showcase of 1980s animatronics.

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders is a different kind of horror movie. Its imagery may well haunt you as if recalling your own deliciously disturbing dreams. It bravely, yet sensitively, broaches taboo and confronts the confusion arising between aesthetic and sexual attraction. The power of sexuality, as a drive within oneself, and as a manipulative power over others. Fear and power. The subjugation of sexual energies by authority and the church. Shame as a method of control.

Whilst celebrating the inner life of the child, it mourns the end of innocence. Coming-of-age means coming to terms with having to grow up and letting go of childish things. This is the tragedy that threatens Valerie: the loss of childhood, without fully understanding what will replace it. The story’s most profound point is that one doesn’t have to ‘kill the child’ to become an adult. There is a continuation of selfhood. That realisation can be truly empowering and with it, profound happiness can be found.

CZECHOSLOVAKIA | 1970 | 77 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | COLOUR | CZECH

director: Jaromil Jireš.

writers: Ester Krumbachová, Jaromil Jireš & Jiří Musil (dialogue). (Based on the novel by Vítězslav Nezval.)

starring: Jaroslava Schallerová, Helena Anýžová, Petr Kopřiva & Jiří Prýmek.