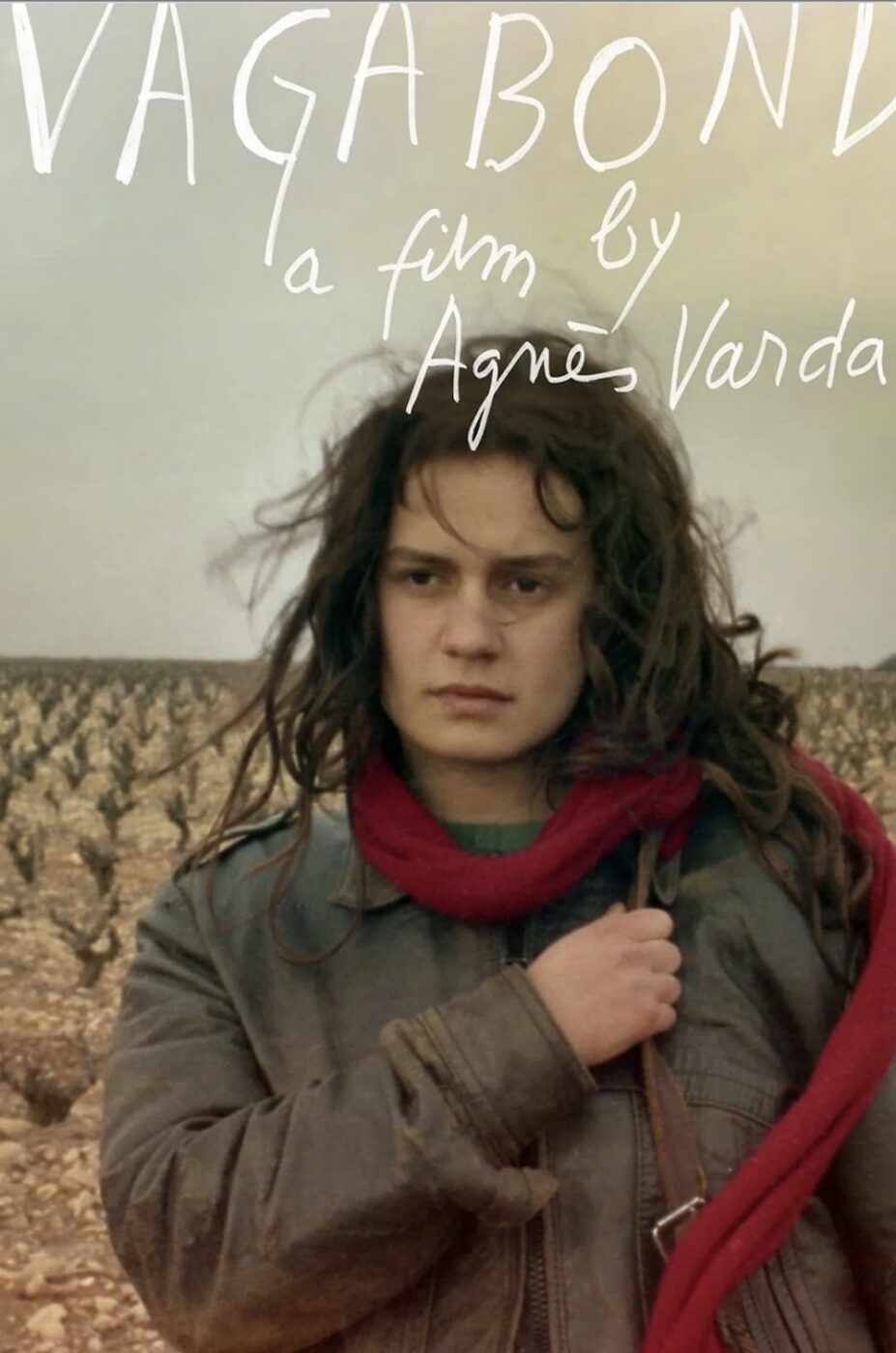

VAGABOND (1985)

A young woman's body is found frozen in a ditch. Through flashbacks and interviews, we see the events that led to her inevitable death.

A young woman's body is found frozen in a ditch. Through flashbacks and interviews, we see the events that led to her inevitable death.

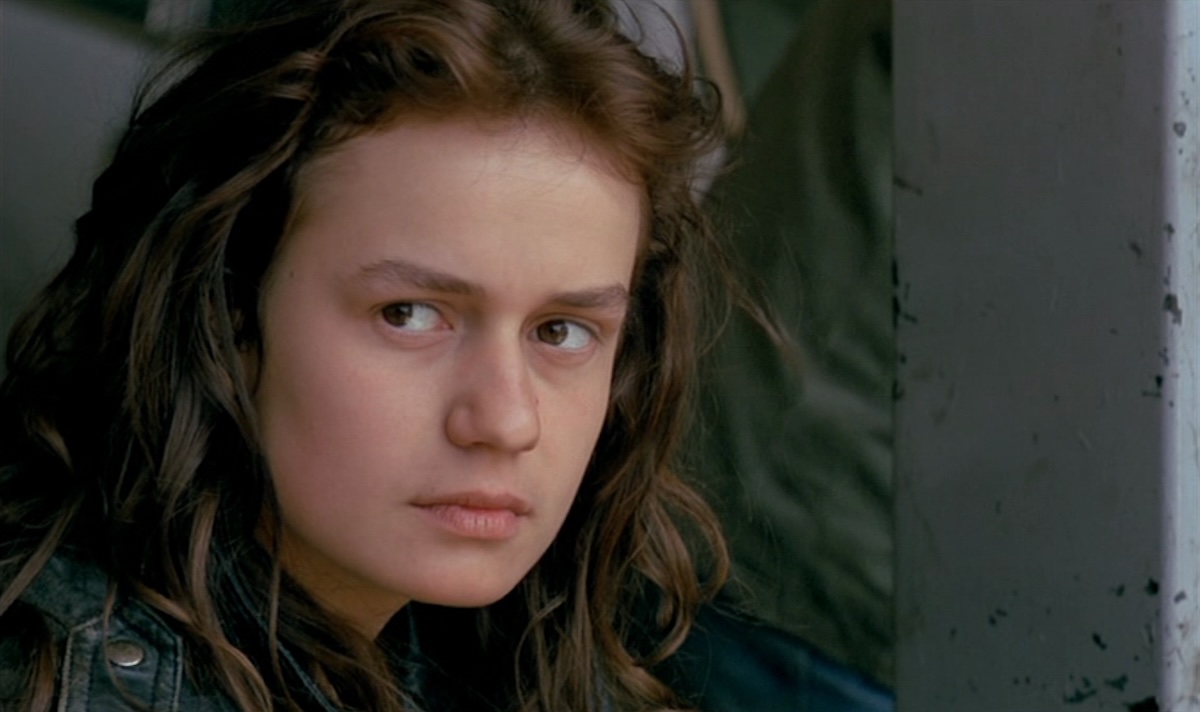

Death frames Agnès Varda’s Vagabond / Sans toit ni loi. At the film’s outset, a mysterious woman’s corpse is found, her cold, stiff body that of someone without a home to call her own or people to rely on. A woman whose life cannot be understood in the slightest by most onlookers, Mona’s (Sandrine Bonnaire) backstory and outlook are gradually revealed through a series of flashbacks and pseudo-documentary footage, where people who came across her during this time reflect on who she was. These subjects are often wrong in their assessments, though it’s difficult to say whether or not they are wilful liars. It’s the strictly fictional elements of Vagabond that present the film in its most truthful state, where we are no longer bound to a specific perspective on Mona’s character, but can directly witness the events which unfolded in Mona’s recent past.

Some of these observers of—and brief participants in—Mona’s life are hilariously hypocritical, like the mechanic who ruminates that young women like Mona shouldn’t be entertained for long, since they are temptresses eager to lure in men rather than do anything productive with their time. When he stares at her moments later in the film, and long before this in Vagabond’s chronology, it takes little more than a second to identify the lust lurking within his expression. And when he emerges from her makeshift tent, struggling to put his trousers back on, one has no doubt that this was a paid arrangement. Whether it’s through their dialogue as documentary subjects or their curious expressions in flashback scenes, these characters’ perception of Mona and intentions on how to treat her are clear as day.

Curiously, this particular scene is shot from the perspective of another worker at this mechanic’s, who, looking out for Mona, is only able to glimpse her hands as she shuts the tent behind her. She’s a mystery to him, and he a mystery to her. We don’t even see his reaction to the unfurling drama; it’s all clouded in intrigue and a presumed feeling of betrayal. They had never had a relationship, but there could have been something, and this alone is enough reason to despair. At least, those are the projections you are led to hoist onto this onlooker, just as these men hoist their biased perceptions of Mona onto her, seeing only what they want to.

This is a film full of presumptions by the many people who encountered Mona in the final months of her life, almost all of whom are totally unaware of how pig-headed they sound in their derisive comments towards this young woman. But even with a silent and unknown interviewer in the interview portions of the film, there remain trials and tribulations of the heart that go unnoticed.

Key moments in this narrative, or pieces of Mona’s life that feel essential to uncovering more about her, are left out entirely. As they are washed away in time, a collage of impressions of an ultimately unknowable woman are cobbled together through the endlessly rocky terrain of memory. The crisp cinematography works wonders when accompanied by Varda’s sprightly direction, where camera movements and point-of-view shots emerge or glide so gracefully that one can’t help but marvel at their light touch. They are beautiful even when depicting dire conditions, and mirror the unconventional beauty of Mona’s lifestyle, which very few of the near-strangers who encountered her can appreciate.

In documenting Mona’s life, a portrait emerges of a headstrong woman eager to take a chance on the unknowable qualities of life. Naturally, this makes her unknowable to almost everyone who encounters her. This is especially true when this story’s men, upon encountering her, are overflowing with notions of how her life should be lived. There’s a mix of patronisation, fetishism, and genuine concern in each of them, where they are horrified by a wayward lifestyle being dictated by a young, attractive woman. As a vagabond without any fixed abode or long-lasting connections, Mona is impossible not to pity and be frustrated by. She overlooks her personal safety to a maddening degree.

But there’s something emboldening about her headstrong, matter-of-fact approach. You feel like cheering her on, but that’s the last thing these observers would think to do. When some of these men speak about her in retrospect, they only ever reveal interesting reflections about themselves. It’s never intentional, of course, but they’re too narrow-minded to see that. The coarseness they see in Mona’s circumstances and dirt-stained appearance is reflected acutely in their own prejudices, but it remains difficult to say whether or not such pronouncements are completely wrong.

Am I simply blind to the whims that overtook this protagonist and made her abandon the civilised world entirely, or is it only right to question an attractive young woman—who could perish at the hands of nature and man alike in such unforgiving conditions—choosing to forgo the creature comforts that almost all of us couldn’t bear to live without? Of course, I’m biased towards falling into the latter category, but Varda wisely chooses to ignore offering any pronouncements of her own, leaving that task for the people who encountered Mona.

This doesn’t mean that Varda is uninterested in mythology. Vagabond might seem like a rather bitter polemic on how innately judgemental people are, or how the qualities we ascribe to others only end up reflecting our own aberrant qualities. But there’s something deeper and more tantalising at play here. One must thank the cinema gods that it was Varda who followed through with this idea rather than the likes of Lars Von Trier or Ulrich Seidl, two filmmakers I respect who would surely have pulverised any semblance of humanity in this poor woman’s life to hammer home their bitter misanthropy. Sexual assault is never far from one’s mind when watching Mona wander through unknown territory with only the clothes on her back and a few belongings in tow, but thankfully the story chooses not to make this one of its focal points (even if it does, inevitably, rear its ugly head).

The tantalising qualities of this film run much deeper than Varda resisting shock value. It questions the role of an objective reality (even when purporting to present it through the re-enactment scenes in Vagabond) by showing Mona’s dead body, then a hazy image of her emerging from the beach, as if she has just washed up on the shore. This is confirmed by a narrator who says that she heard that Mona first came from the sea, as if she’s a mythological being existing on a different plain to us all. Throughout the film, there are many moments that would seem to confirm this, but there are just as many scenes where Mona is a fallible person seeking out comfort and wellbeing the only way she knows how. The truth is that both images—the nymph-like beauty emerging from the water, and the cold, stiff body that became her final form above ground—don’t do this woman justice on their own. They are each half-right in how they interpret who she was and what her existence signified.

Another film about a drifter who found purpose in eschewing the typical comforts and habits of everyday life, Into the Wild (2007), ended with protagonist (and real-life figure) Christopher McCandless (Emile Hirsch) writing that happiness is only real when it’s shared. In Vagabond, this is one of many questions worth asking about Mona. Her life remains a mystery even after her death. Once she’s gone, all that is left are the memories, and they’re never enough. They don’t create a full portrait of a person, they’re scattered, they’re blown to pieces from time, and they’re surrounded by judgements that are so biased and laced with patronisation that one has to wonder whether these interviewees are truly blind to their warped reality.

What is a person made of, and how can you sum that up? Our memories of them? A photograph? A private diary of their innermost thoughts? A video document of the most important moments in their life? Vagabond is a deeply empathetic film that doesn’t seek to canonise or vilify its subject, while recognising that our propensity to do this to other people is bottomless. What is also bottomless is the search to uncover who this woman really was, who is portrayed so sublimely by Bonnaire that you feel as if you know her well, even as you find you’ve spent over an hour in her company and are still left scrutinising her every move and expression.

There could always be more. More interview participants, more memories, and more filmed segments, whether from earlier in Mona’s life or beyond the grave. It isn’t just for the sake of brevity, or to construct a tantalising, rich world that Varda doesn’t focus on these absent moments. She’s well aware that it would never be enough. The search always continues, even after death, and the only truth we can ascribe to this process is that we know so little about it.

Even the most obvious of things, staring us directly in the face, filmed for our viewing perusal time after time again, can remain unknowable. It’s a terrifying, timeless concept profoundly articulated by an iconic filmmaker, who left many remnants of her soul throughout her filmography before her passing less than a decade ago. Even she remains unknowable, as do we all. Whether it’s through the film’s acting, cinematography, shot selections or character analysis, Vagabond doesn’t show its age whatsoever, though its timelessness will only become more appreciable in the coming decades, as all the key players in this wonderful film are no longer alive and the mysteries refuse to die with them. The only facet of the movie that doesn’t hold up is its score, which insists on terror and tension at every turn. Joanna Bruzdowicz and Fred Chichin’s repetitive soundtrack provides easy answers to impossible questions, and Vagabond, thankfully, does anything but that.

FRANCE • UK | 1985 | 105 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | COLOUR | FRENCH • ARABIC • ENGLISH

writer & director: Agnès Varda.

starring: Sandrine Bonnaire, Macha Méril, Stéphane Freiss, Yolande Moreau, Patrick Lepcynski, Joël Fosse, Patrick Lepcynski & Pierre Imbert.