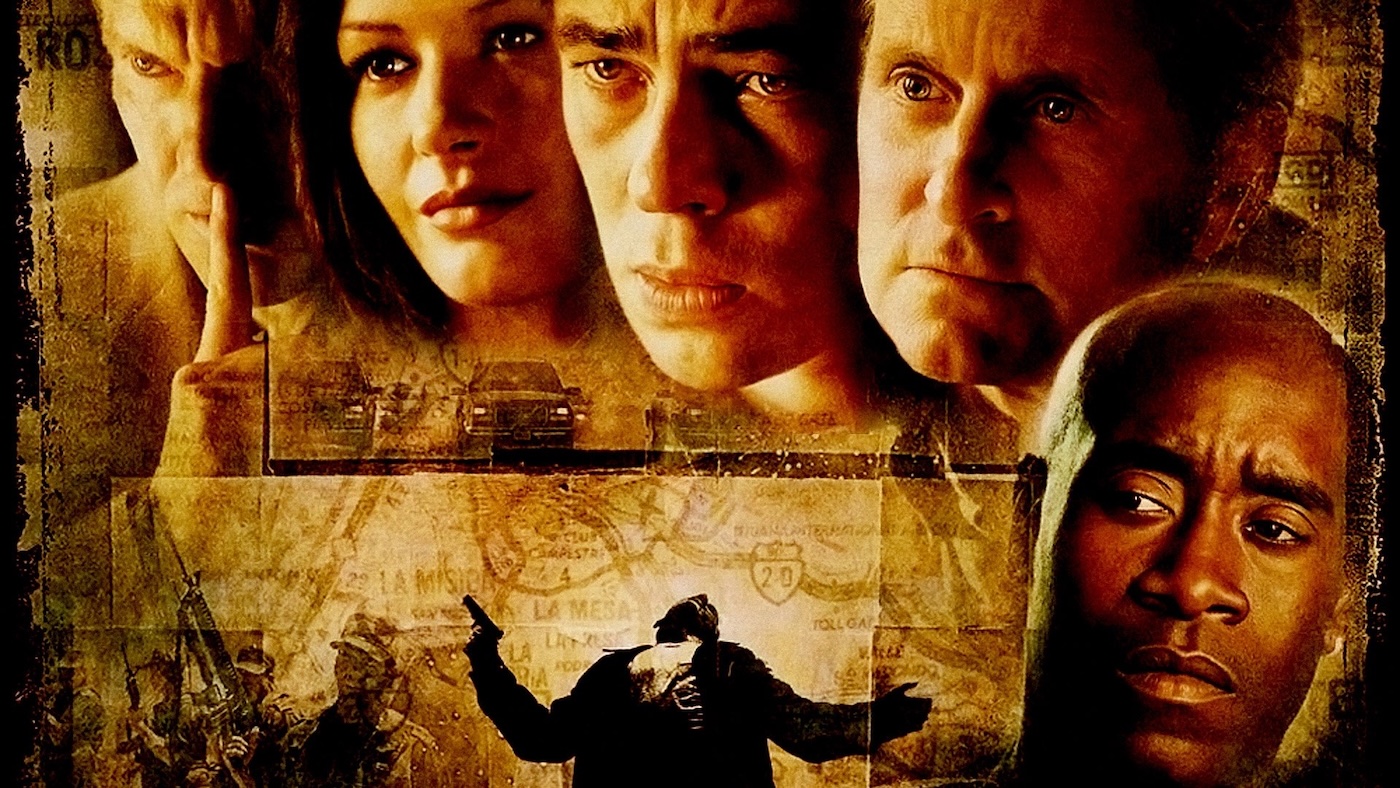

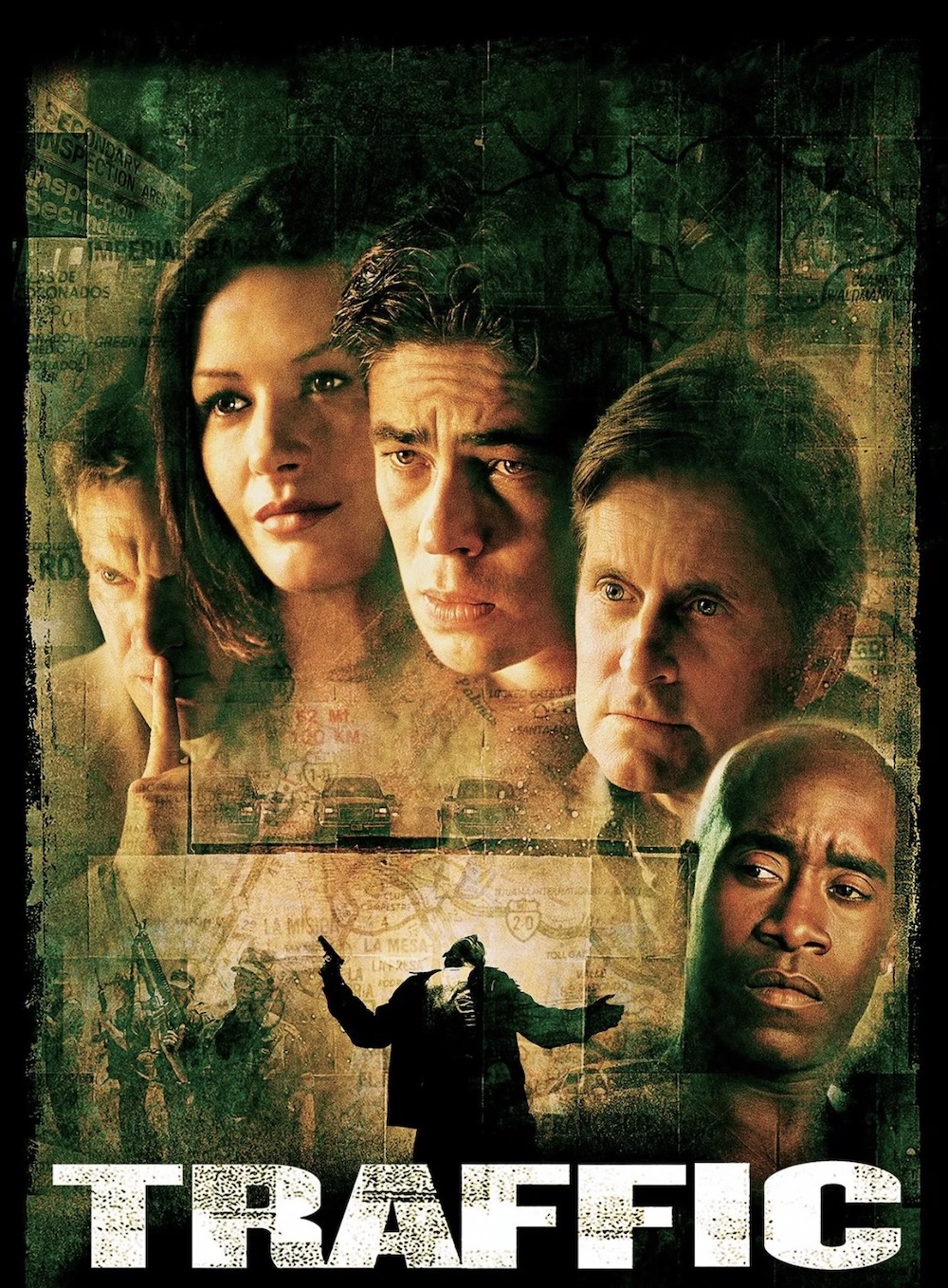

TRAFFIC (2000)

A judge is appointed to spearhead America's escalating war against drugs, only to discover his daughter is a crack addict. Two DEA agents protect an informant. A jailed drug baron's wife attempts to carry on the family business.

A judge is appointed to spearhead America's escalating war against drugs, only to discover his daughter is a crack addict. Two DEA agents protect an informant. A jailed drug baron's wife attempts to carry on the family business.

Steven Soderbergh has rightfully earned his reputation as one of the most stylistically varied directors in modern cinema. Whether he’s dealing with surrealist comedies or independent dramas, he makes each entry in his filmography distinctly his. The American director was especially prolific in 2000, helming both Erin Brockovich and Traffic, two box office successes with high-profile performers. Both films did not shy away from bleakness, but they were warm and empathetic towards the innocent victims and powerless rebels dwarfed by industries that tear people apart.

Not long before Americans rallied behind their country more strongly than they had in years after the 9/11 attacks, both of Soderbergh’s 2000 features unveiled themselves as fiery attacks on major US corporations or governmental systems, whether for direct policies or tacit endorsement of abhorrent practices. Each film was impassioned and weary, prioritising the struggles of ordinary people in an unjust world. While Erin Brockovich honed in on the struggles of its eponymous single mother, Traffic skips back and forth between the US and Mexico throughout its 140-minute runtime, boasting a multi-story, transnational plot.

Despite both films’ differences, you can instantly tell that they were made by Soderbergh. He has an uncanny knack for making movies that feel like they have a simultaneously independent and mainstream sensibility. Traffic refuses to bask in its characters’ horrific situations, of which there are many. The film does not just quickly pivot to different plot lines, it’s light on its feet even in a given scene. These characters never get time to contemplate their fate; they’re too busy living it out.

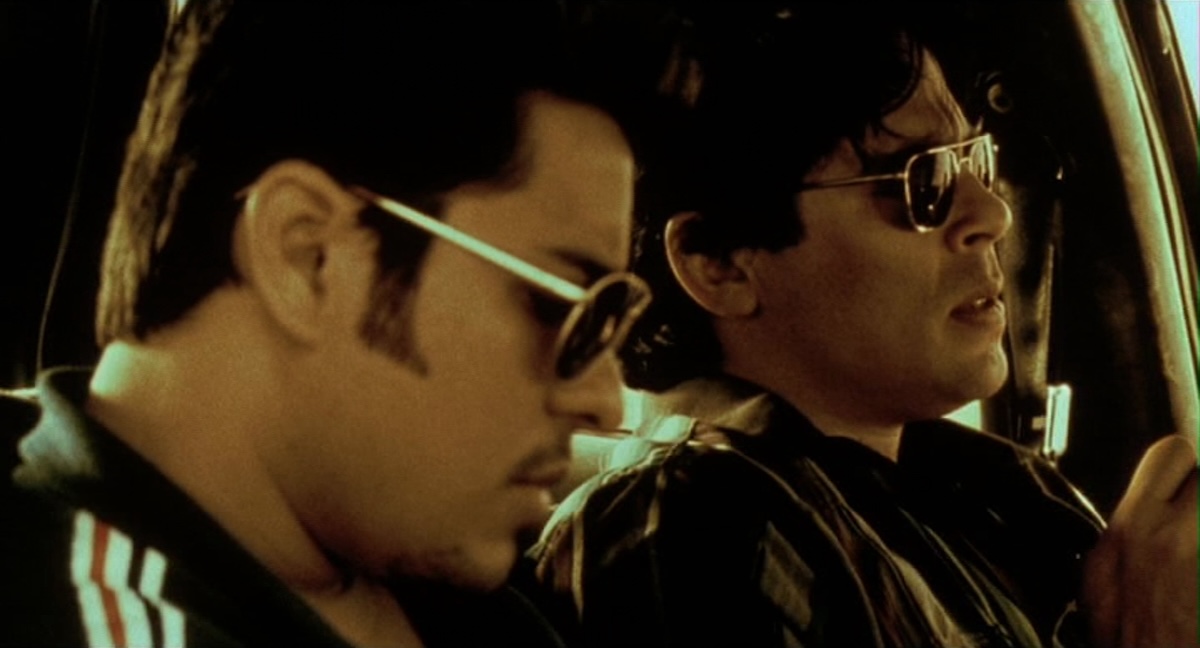

Some sequences could benefit from more silence to hammer home their dramatic beats, as is executed so brilliantly in a speech late in the film. But on the whole, Traffic’s fast pace is welcome, especially given how much plot it has to work through for all this story’s pieces to come together. The film never shies away from the consequences that befall these characters, while its handheld camerawork makes it seem as though they’re always on shaky ground. It’s a stylistic move that mirrors both their mental and physical wellbeing. Many of them could be killed at any moment, a possibility they’ve had to reckon with and accept.

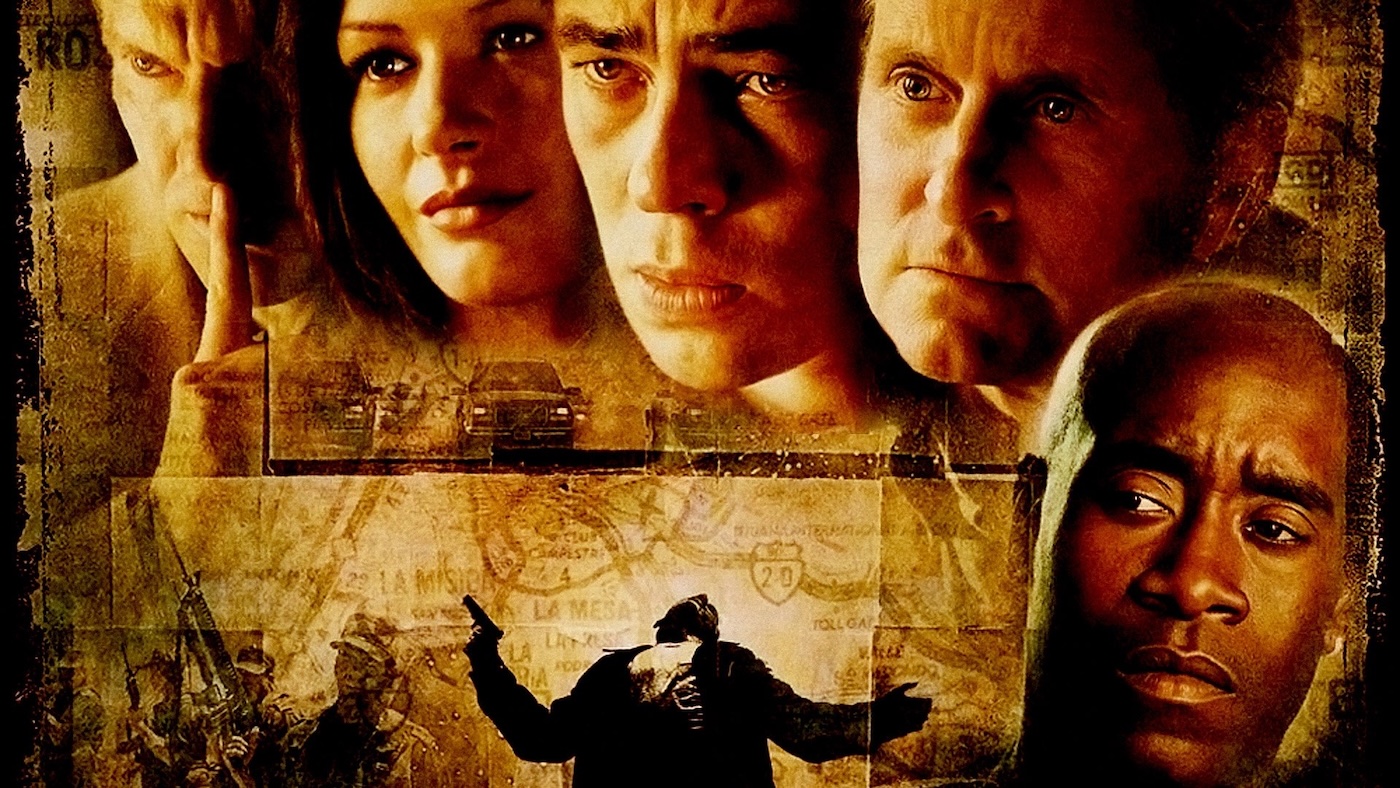

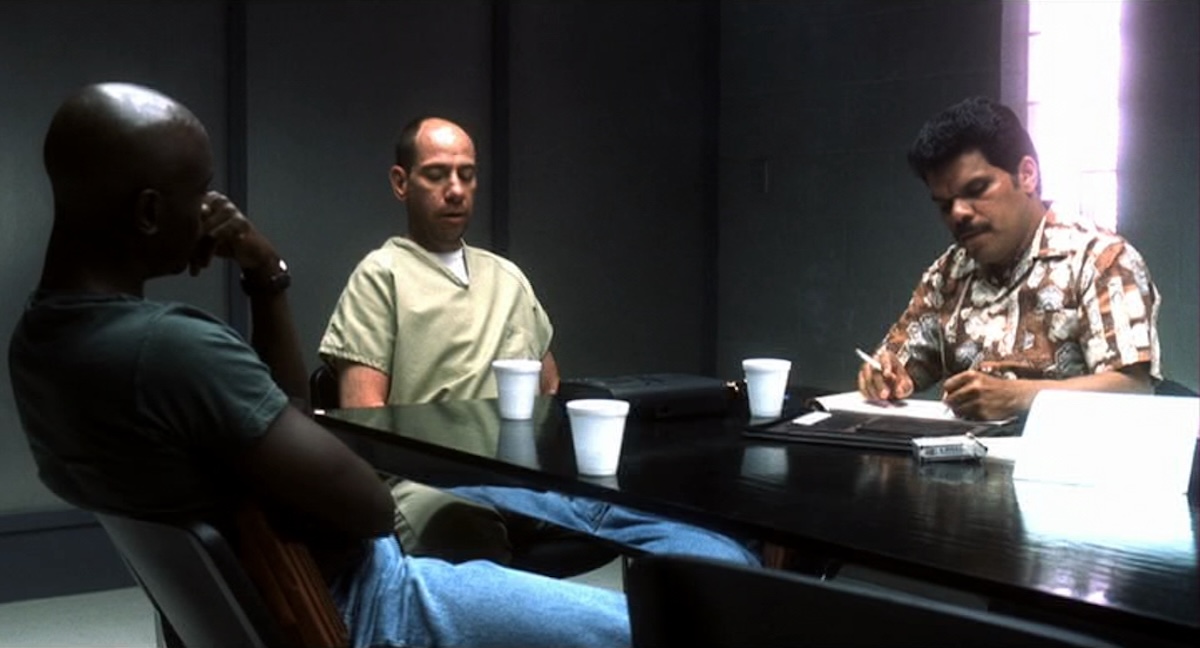

Soderbergh’s stylistic inventions are usually a joy to witness, if only for their originality, but the colour grading in Traffic is absurd. Harsh yellow light washes over the film’s sequences in Mexico, while much of the US-set storylines are doused in blue light. The film’s colour grading is so over-the-top that one couldn’t blame prospective viewers for assuming that something has gone radically wrong with the colour on their television. Erin Brockovich had a similar sepia-coloured tint as this film’s Mexico-set scenes. While both techniques lack purpose, Traffic’s glaring contrasts take it to an absurd proportion.

This isn’t the only dated quality in the film. Its parallel storylines, though admirable, never manage to convey its subject matter’s complexity. These plotlines are so bare-bones that they almost feel self-contained, if not for the fact that they each need to progress in tandem for this story’s chain reactions to occur. While Soderbergh’s camerawork is ideal for orienting people in their environments, he does little to flesh out the characters. The urgency of the present moment reigns supreme. It often needs to, with youngsters succumbing to drug addiction and members of law enforcement fruitlessly trying to enact justice. But most of these characters are missing a personal element. If it does exist, you can be damn sure it will directly impact the plot. The story strains to wrap itself around its plot of chain reactions, rather than making these developments feel illuminating.

Didacticism certainly doesn’t help, even if Stephen Gaghan’s screenplay is mostly tasteful; only a few heavy-handed scenes spoil one’s immersion. When Traffic isn’t honing in on its messaging and remembers the lives wrapped up in its cyclical plot, it’s frequently moving. Robert Wakefield, the President’s new drug czar, is wracked with worry over his daughter Caroline’s (Erika Christensen) drug addiction, such that everything this role requires of him suddenly appears meaningless. It’s all empty platitudes and puffing out one’s chest, as if this impotent strong-arming could possibly stem the various ways that the presence of drugs ravages a community.

Direct statements that cut through the bullshit are desperately needed, but whether due to political pressure, corruption, or the prevalence of the cartels, such a scenario becomes a pipe dream to imagine. Traffic might be a symphonic soap opera in many ways, but it always makes an effort to hammer home its no-bullshit sentiment. If it were released nowadays… well, it probably wouldn’t be. Its dated didacticism isn’t worlds apart from the multi-story, Academy Award-winning, mostly reviled Crash (2005). It’s just significantly more accomplished on every level. Nowadays, it would likely be a television show, drilling down into these issues in much the same way that David Simon’s The Wire (2002–07) did so maturely.

As it is, not enough time is spent with any of these characters to encapsulate the scope and minutiae of this subject matter, even if it’s invigorating to witness how these storylines connect to one another. The vast majority of films conceal the invisible confluences running underneath society’s pulse, which would surely unite us all if we only had the ability to see them. While it’s easy to critique Traffic’s moral simplicity, it’s so damn earnest that one can’t help but be moved by it.

These characters try to cleanse themselves of responsibility, but Traffic makes it clear that everyone involved is a movable force within wider systems. These figures can never change society for good on their own, and it almost always influences them rather than the other way around. But that doesn’t mean their contribution is worthless. On the contrary, Soderbergh and Gaghan champion small victories.

The film is significantly shorter than the runtime of its first cut, which ran to three hours and ten minutes. As it currently stands, Traffic’s sweeping camera movements and quietly tragic soundtrack cast its various facets of society under the same glare, but more time is needed with these figures to empathise with them beyond these wider connections. It’s easy to see why the movie was loosely adapted from a television show, the 1989 British series Traffik. Its optimism works best as a feature film, binding these characters together into one unforgettable experience, even if some of its goals seem oddly short-sighted. Minor victories must be valued, Soderbergh and Gaghan are keen to remind viewers. Without them, there’s only dissolution. Traffic is many things—brutal and bleak, mainly—but it’s not without hope. Just like its characters’ actions, that is not to be scoffed at.

GERMANY • USA | 2000 | 147 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • SPANISH

director: Steven Soderbergh.

writer: Stephen Gaghan (based on the TV series ‘Traffik’ by Simon Moore).

starring: Benicio del Toro, Don Cheadle, Michael Douglas, Erika Kristensen, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Luis Guzmán, Jacob Vargas, Topher Grace, Tomas Milian & Steven Bauer.