THE LAST EMPEROR (1987)

Crowned Emperor of China at the age of two, Puyi finds himself a prisoner in his own palace.

Crowned Emperor of China at the age of two, Puyi finds himself a prisoner in his own palace.

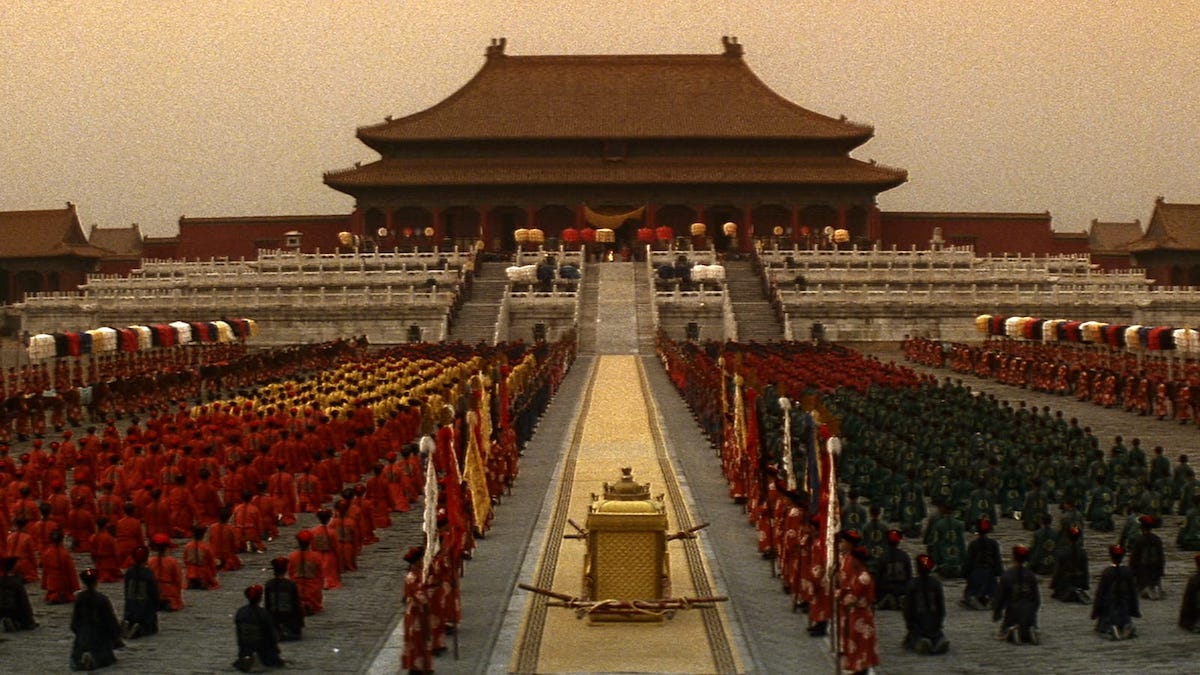

Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor starts as the director means to go on, with a still image of the Forbidden City in Beijing—for centuries the palace of China’s emperors—tinted red. His film is full of the colour: mixed profligately with gold in the breathtakingly lavish palace during the last days of the empire; in the lipstick smears on the head of the young emperor after his first intimate scene with his new wife; and in the blood that fills a basin when he tries, years later, to commit suicide rather than live as a prisoner of the Maoists. The scenes devoid of red (and gold) are all the more noticeable for lacking it.

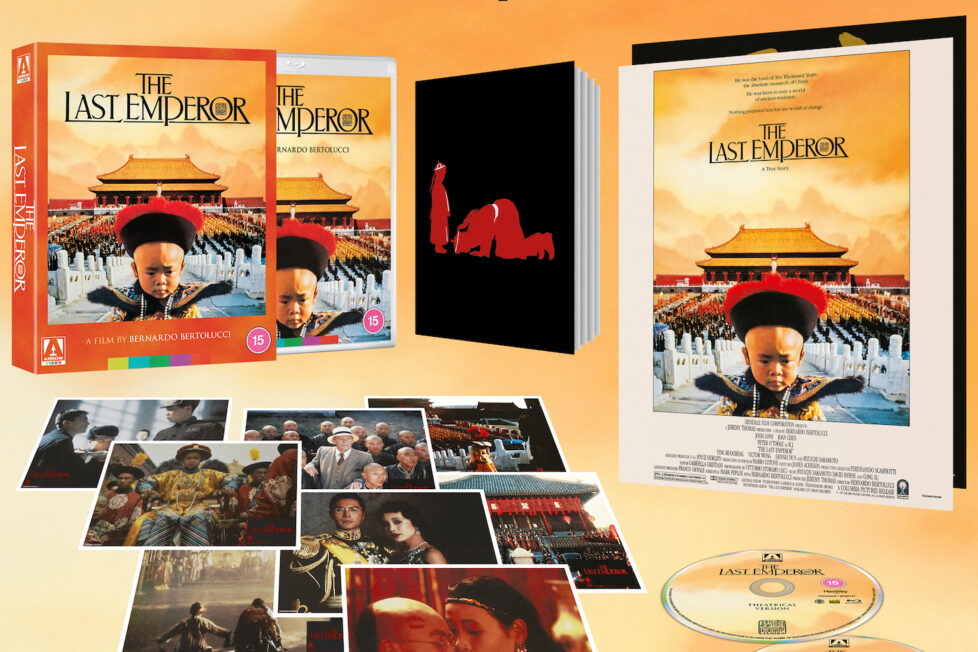

Indeed, it’s more than possible for the extreme opulence of The Last Emperor—19,000 extras! The first movie filmed in the Forbidden City!—to distract from the human story, and it’s difficult to avoid a feeling there’s a slight emptiness at its heart. How much this is intentional is open to debate, however, as part of Bertolucci’s point is surely how the position of emperor, and indeed the positions of those surrounding him, overwhelmed the people who held them.

The Last Emperor starts in 1950 with a trainload of “war criminals” arriving at a station in newly-communist China. Most are shabby, although one wears expensive civilian clothes and a few of his fellow prisoners bow to him, despite the risk of incurring the guards’ fury. He’s Puyi, and in better times he was the last Emperor of China, Lord of Ten Thousand Years.

Bertolucci then cuts back to 1908, when Puyi was declared Emperor as a two-year-old child. We see him, uncomprehending, at an audience with the Grand Empress Dowager on the day the old Emperor died. Some of the reality of his new situation soon enough starts to dawn on him—“is it true I can do anything I want?” he asks—but it’s not until he’s older that he discovers this freedom is illusory.

Within the Forbidden City he may nominally hold all the power, and when the laughing little boy runs out of the throne room into the great square, the parading soldiers immediately bow to him. But he’s manipulated by courtiers (when more mature, in fact, he will fire the vast, corrupt staff of eunuchs), and by 1912 they’ll not even allow him to leave the palace. China has become a republic, and he’s really Emperor of nothing; the Forbidden City was, he observes at one point, “a theatre without an audience”; the British tutor (Peter O’Toole) brought to educate him describes him as “the loneliest boy on earth.”

As Puyi grows older his childish wilfulness gives way to a more adult assertiveness, although it’s difficult to know how far he’s really grown up, given his almost completely disconnection from normality. Even on his wedding night, servants are there to undress him. But he does argue for reform and modernisation. He cuts off his queue (pigtail), to the horror of his more conventional attendants; he loves western things, from pianos to Wrigley’s gum, and he wants a wife who can dance the quickstep. When he is told he needs glasses, he delightedly exclaims “like Harold Lloyd!”

Periodically The Last Emperor returns to the 1950s and Puyi’s later life under Communism, but for the most part it follows the story sequentially. After more political upheavals in China, he leaves the Forbidden City and relocates to Tianjin, taking the name Henry Pu Yi and living the life of a monied playboy; he’s then co-opted by the Japanese to become Emperor of Manchukuo, an area of northeast China bordering the Sea of Japan which they’d seized from the Chinese.

But he’s nothing more than a puppet of the conquerors, and when the Japanese are defeated at the end of World War II he falls into the hands of first the Russians and then the communist Chinese. As ‘Prisoner 981’, the man who was once the child Emperor now sweeps floors and cleans toilets while undergoing “re-education.”

The film is best seen as impressionistic or symbolic in the way it depicts Puyi’s changes in fortune; there are plenty of factual inaccuracies, not least the portrayal of his captivity under the communists as relatively benign, and the years he spent in Russian hands are mostly skipped over. And much more of its effect comes, in any case, from the visual than from the narrative. Though Bertolucci had maintained years earlier that “all my films are documentaries on my actors”, in The Last Emperor the settings and the photography are at least as important as the people.

Bertolucci and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro are at their best in the timeless grandeur of the Forbidden City, but they create strikingly beautiful smaller-scale moments too; young Puyi and his brother Pujie playing with the palace staff, the older Puyi with his two wives hidden beneath a peach bedsheet, a yard of prisoners playing table tennis much later on. Even a rescue from a rooftop, one of few action-oriented sequences in The Last Emperor, is gorgeously shot.

In Manchukuo, the decrepit concrete factories in the background behind Puyi’s golden throne encapsulate the contradictions of his position. The score by Sakamoto, David Byrne, and Cong Su, similarly, embraces the conflicting forces in his life, sometimes written in completely western style (there is even one distinctly Wagnerian passage), but at many points mixing western tonality with Chinese timbres and textures; a Chinese orchestra playing “Auld Lang Syne” as Puyi’s tutor departs for England is only the most extreme example of this culture-crossing.

Colour is significant throughout: huge fields of red abound in the Emperor’s younger life, but hues become darker once he falls under the influence of the Japanese, and then fade to drab olive and grey for the communist era. Repetition is used effectively, too: palace gates are closed by soldiers in two very different sets of circumstances, the bicycle his tutor introduces to the Forbidden City foreshadows the crowd of cyclists Puyi joins at the very end. There at the conclusion, too, is a hint that perhaps not much has changed after all: the parade with pictures of Mao Zedong (and Red Guards), dancing girls and an accordion band is oddly similar to some of the ceremonies of the imperial era.

Even so, there are times where personality comes through. Puyi’s treatment of his pet mouse in two scenes illustrates his changing state of mind; a scene where he orders a servant to drink ink, to prove his power and the loyalty he commands, is offered without comment but chilling in its implications. Perhaps most memorable of all is the moment where his “secondary consort” Wenxiu (Vivien Wu) goes out in the rain, throws down her umbrella, takes off her hat and exclaims in wonder: “I do not need it!” She has finally realised that they can escape from the stifling coddling of their position.

Given its heavily visual emphasis, The Last Emperor is not primarily an actors’ movie and Peter O’Toole was the only major name in the cast, although John Lone (one of several actors in the title role) was becoming known and Ryuichi Sakamoto had attracted attention with his debut in Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence (1983)—for which, as here, he also composed music.

O’Toole does little more with his part than one would expect, but there are some interesting performances in minor roles, among them Maggie Han as Eastern Jewel—a cousin of the Emperor, flapper, and self-declared spy—as well as Ric Young playing an aggressive Maoist interrogator and Ying Ruocheng as a prison governor. Ruocheng had himself been a victim of Mao’s Cultural Revolution but had recovered his reputation to the extent that by the time of The Last Emperor he was China’s vice minister for culture, and he would play a major role in Bertolucci’s Little Buddha (1993) too.

The movie is naturally dominated, though, by the four performers—in age order Richard Vuu, Tijger Tsou, Wu Tao, and finally Lone, who plays Puyi—and all are impressive. Inevitably, the appropriately-named Lone, as the adult man, is the one most associated with the part but Tsou in the difficult role of the eight-year-old Puyi and Tao as the teenage boy are if anything even better. British film critic David Thomson described Puyi as “a figure so pampered that he hardly has identity”, and Bertolucci’s film does leave somewhat undetermined the question of how far he was a passive victim and how far he had real agency, yet all four actors manage to suggest that there is an identity there, buried somewhere in all the coddling and politics.

The Last Emperor swept the Academy Awards, earning not only the ‘Best Picture’ award but also eight others including those for ‘Best Director’, ‘Best Adapted Screenplay’, ‘Best Cinematography’, ‘Best Score’, ‘Best Art Direction’ and ‘Best Costume Design’. It’s a movie of its time—essentially a European’s view of Oriental exoticism in which Bertolucci treats China much as he would Bhutan and Nepal in Little Buddha—and can seem a little dated as a result. It’s also difficult to determine where Bertolucci’s sympathies are. He was a passionate Marxist, had been a member of the Italian communist party, and certainly paints a rosier picture of life under Mao than many would… but, however much it might go against his ideological convictions, it seems he can’t quite resist the pomp of imperial China either. The camera never lies?

The film could be fairly criticised, too, for a certain sense of detachment. The broad history of 20th-century China and the personal history of Puyi are, ultimately, only pretexts here for delicious imagery and dramatic moments; there’s rarely a feeling that we are really gaining any understanding of them, or that Bertolucci is particularly interested in offering that. Still, The Last Emperor is a sweeping, immersive historical epic of a kind rarely made today, and made so exquisitely that it is almost impossible not to relish it.

CHINA • ITALY • UK • FRANCE | 1987 | 163 MINUTES (THEATRICAL VERSION) • 219 MINUTES (EXTENDED VERSION)| 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • MANDARIN • JAPANESE

This longer (219-minute) version is sometimes erroneously described as a “director’s cut”, but it is emphatically not that in the normal sense.

Although this cut was shown theatrically in Asia, Bertolucci padded the story out with extra footage specifically to create a four-part series for Italian TV, the 163-minutes of the film proper not being long enough for that purpose. He himself described it as “a version that in my opinion is not much different from the other one, just a little bit more boring”. So, while it may be of interest to completists, it is if anything the opposite of what we normally consider a “director’s cut”.

director: Bernardo Bertolucci.

writers: Mark Peploe & Bernardo Bertolucci (based on the book ‘From Emperor to Citizen: The Autobiography of Aisin-Gioro Puyi’.)

starring: John Lone, Joan Chen, Peter O’Toole, Ying Ruocheng, Victor Wong, Dennis Dun, Vivian Wu & Ryuichi Sakamoto.