MERRY CHRISTMAS, MR. LAWRENCE (1983)

During WWII, a British colonel tries to bridge the cultural divides between a British POW and the Japanese camp commander in order to avoid bloodshed.

During WWII, a British colonel tries to bridge the cultural divides between a British POW and the Japanese camp commander in order to avoid bloodshed.

Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence is a welcome release from Arrow Academy. Its director Nagisa Ōshima is neglected in comparison to more venerated Japanese directors like Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, Naruse, and Ozu. An iconoclast auteur who rejected their “sense of resignation, acquiescence in traditional passive modes of being Japanese, and then nostalgia at their passing”, Ōshima was more concerned with holding up a mirror to post-war Japanese culture and society. He actively challenged “the victimhood he saw everywhere in the psychic make-up of his fellow Japanese” and the old societal values preserved after World War II.

Ōshima rejected the status quo of the Shochiku Ofuna studio system to make politically aggressive films. When Shochiku denounced the messages of his first film, A Town of Love and Hope (1959), and pulled the distribution of Night and Fog in Japan (1960) because it supported the student opposition to the renewal of a security treaty between the US and Japan, he resigned and set up his own production company called Sozosha. When he couldn’t get funding in Japan he pursued international co-production to continue to use cinema “as a medium for the exploration of unknown territory.”

His notoriety in the West rested on the sexually explicit and violent In the Realm of the Senses (1976), in which a married man and a geisha reject the strictures of a repressive, militaristic Japan in 1936 by escaping into their sexual fantasies. It was based on the real-life story of the affair between Abe Sada and her boss Ishida Kichizō. After several bouts of erotically asphyxiating him, she then strangled the sleeping Ishida, cut off his genitals, and took them with her. The police were unconvinced Sada had committed the crime until she revealed her trophies and explained that, whereas the castration was intentional, the strangulation was accidental.

Oshima’s film was, in part, his response to French producer Anatole Dauman’s offer in 1972 of “let’s make a porno flick!” Dauman, who’d produced films with Alain Resnais, Jean-Luc Godard, and shown some of Oshima’s early work in Paris, raised the money for the film and offered Oshima the freedom that came with co-production, “to show whatever we wanted” in contrast to the simulated sex and onscreen masking of genitalia in the popular softcore Japanese Pinku eiga ‘pink films’ of the period.

Beyond its explicitness, Senses engaged with the political themes and challenges to authority he’d been celebrated for and extended the thematic use of outcasts, crime, violence, prejudice and delinquency (often based on real cases) found in A Town of Love and Hope, The Sun’s Burial (1960), Violence at Noon (1966), Death by Hanging (1968) and Boy (1969), and the politicisation of the family unit explored in The Ceremony (1971). A maverick filmmaker, it was often difficult to pin him down to any specific movement, genre, or style, but the themes of sexual and political repression were a constant in his work.

Oshima worked with Dauman again on Empire of Passion (1978), a film set in Edo-period Japan that’s perhaps Oshima’s only contribution to the kaidan (Japanese ghost story) genre and, as Rayns notes in the profile on this Blu-ray disc, it was quite the opposite to the explicit Senses. Suffice it to say, Dauman didn’t get what he expected and ended the relationship with Oshima.

Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence expanded Oshima’s international reputation. More importantly, it reflected some of the themes of Oshima’s The Catch (1961). Based on Kenzaburō Ōe’s award-winning novella, it depicts how a black US airman becomes a prisoner of war after being captured by the occupants of a small village. Oshima exposes Japanese hypocrisy, racism, and xenophobia as a power struggle ensues over the way the village should treat their prisoner, now a scapegoat to justify their torture and abuse.

Merry Christmas returned to the Pacific War and the treatment of prisoners of war in an adaptation of South African writer Sir Laurens van der Post’s 1963 novel The Seed and the Sower. Published in Japan in 1978, Oshima was immediately taken by its story, based on van der Post’s own experiences when Japan invaded South East Asia in 1942. Interned in the Sukabumi and Bandung Japanese prison camps in West Java, he was tortured by the Japanese. He revealed some of the psychological trauma in A Bar of Shadow, a story originally published in 1956 and then included in the book: “it is one of the hardest things in this prison life: the strain caused by being continually in the power of people who are only half-sane and live in a twilight of reason and humanity.”

Van der Post was a celebrated polymath; a blend of environmentalist, political consultant, and, supposedly, Jungian guru. He advised Prince Charles, was godfather to Prince William, and a confidant of Margaret Thatcher. Yet, in 2001, he was exposed as a charismatic fantasist and liar, particularly about his pre-war private life. By all accounts a hugely influential, brilliant storyteller, it became increasingly problematic knowing where the fact ended and fiction began.

According to Roger Bourke, the stories in The Seed and the Sower are an “amalgam of the experienced and the researched” and his 1954 novella A Bar of Shadow apparently drew its inspiration from unpublished documents about “the internment in Singapore of British civil servant Rob (later Sir Robert) Scott, and the trial and execution of a Japanese soldier for war crimes.” In J.D.F Jones’ Storyteller: The Many Lives of Laurens van der Post, a book vilified by van der Post’s daughter Lucia Crichton-Miller, his claim he volunteered for extra beatings by his Japanese captors to save his fellow prisoners was disputed in statements made by said inmates.

However, this wasn’t public knowledge when Oshima adapted The Seed and the Sower. Even if it’s only partly based on van der Post’s experiences, it’s highly regarded and, in 1963, was deemed by Kirkus Reviews to possess “a mystic sense of meaning made incarnate.” For van der Post, the book was an opportunity to explore the battle of wills between British and Japanese officers, the contrast between East and West philosophies, codes of honour and culture, and the unusual bonds these conflicts eventually create. A Bar of Shadow is a first-person account of the relationship between British officer John Lawrence and senior guard Sergeant Hara. The second story is a third-person narrative using the diary of Major Celliers, a South African officer serving in the British Army, who died in the camp. It details the psychological connections with his disfigured brother and with Captain Yonoi, the camp commandant.

A Bar of Shadow, where Lawrence relates to a narrator the story of his release from solitary confinement by Hara on Christmas Eve, is almost intact in the film’s script. The narrator then learns that Hara, having been arrested for war crimes, asks to see Lawrence on the eve of his own execution. Forming the tragic coda of the film, Hara’s departing words are “Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence”. The battle of wills, expressed well in the film, between Lawrence and Hara, Celliers and Yonoi, is derived from the second story. It’s both an existential clash between perceived British cowardice and Japanese bravery and the articulation of a repressed mutual attraction between a blonde South African guerilla operative and a Japanese commander. It also feeds in Celliers’ betrayal of his younger brother in South Africa. Much of Celliers’ anti-apartheid stance and the religious overtones in the book are jettisoned by Oshima in favour of new elements: the sexual assault of a Dutch prisoner, Hara’s decapitation of the perpetrator, Yonoi’s sword practice and Celliers’ acts of defiance.

Oshima also powerfully realised the story’s scenes of Celliers kissing Yonoi in front of the assembled prisoners and guards and, after he is left to die buried up to his neck as punishment, Yonoi taking a cutting of Celliers’ hair. The film heightens Yonoi’s attraction to Celliers but Oshima’s script doesn’t explore Celliers’ awareness, in the original story, of his own attractiveness to Yonoi. The third story in the book, concerning Lawrence’s fling with a woman on the eve of the Japanese invasion, only registers very briefly in the film in a conversation with Celliers. It’s used as more of a prompt for Celliers’ confession about his brother.

When Oshima reconnected with British producer Jeremy Thomas, after meeting at Cannes in 1978, Thomas brought writer Paul Mayersberg on board to undertake rewrites during a visit to Tokyo to promote the release of Nicolas Roeg’s Bad Timing (1980). Mayersberg had written Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and was, at the time, working with Roeg and Thomas on Eureka (1983). Oshima’s first script was about 250 pages long when it was handed over to Mayersberg.

Although the first draft script dealt with Oshima’s depiction of otherness, of interpreting the victim and victimiser and the Japanese mindset from the white British or South African perspective, Mayersberg was asked “to cut, but also to deal with the more English aspects of the characters, who are dealt with in the book, but who through the series of translations back and forth did get lost. Some of it was too discursive and some of it was not explanatory enough. So my work with Oshima, which took two weeks, every day, all day, was to produce a script which was exactly what he needed.”

Originally, Oshima envisioned Robert Redford for the role of blonde, blue eyed Celliers but, meeting with Thomas in Tokyo, he’d been drawn to David Bowie, whom he’d seen in a recent Japanese ad for Crystal Jun Rock sake. He wrote to Bowie and in 1980, during Bowie’s Broadway run on stage in The Elephant Man, Oshima approached him with the idea of starring in the film. Bowie recalled:

He asked me if I’d read the book and I hadn’t. But I had certainly seen a few of his movies and I immediately agreed to do it without seeing the script, because it was such an opportunity, a once-in-a-lifetime experience to work with someone like Oshima.

With Bowie cast, Mayersberg tailored the Celliers role to accommodate Bowie’s abilities as an actor and his training in mime and, in discussions with Bowie, focused on the sense of remorse driving the character. A major alteration was to change the role of Lawrence, scripted by Oshima as an unseen voice-over narrating the story in flashback to Java. Mayersberg made Lawrence the central character so the “narrator was also us and also torn, was not just an observer, and if he made a mistake, it could cost him his life.” Lawrence’s undecided fate then gave the film a real sense of jeopardy.

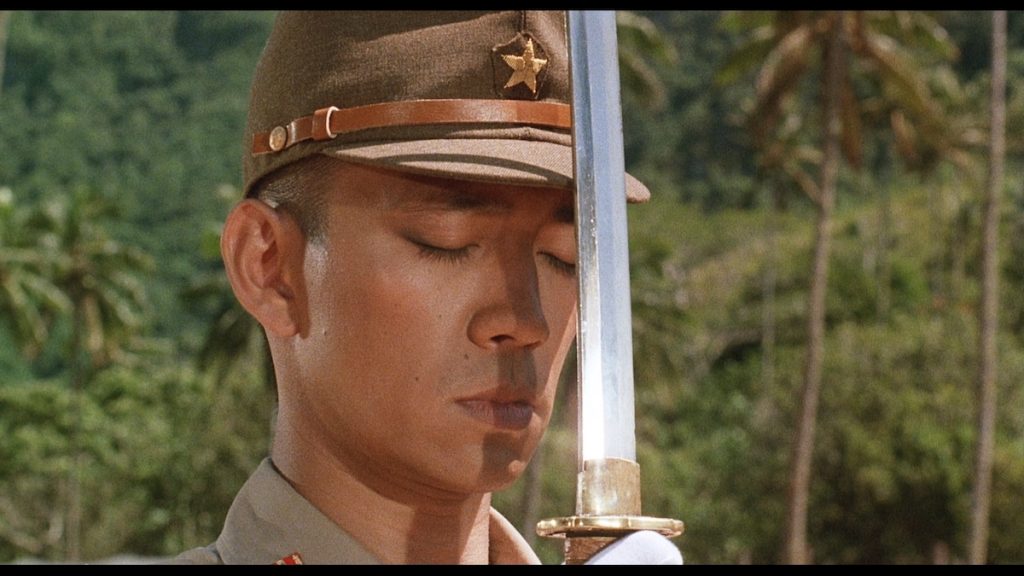

Androgynous singer Kenji Sawada was the first choice for commandant Yonoi, whom Oshima saw as a representation of celebrated Japanese writer Yukio Mishima, but Sawada and another pop star, Tomokazu Miura, were dropped in favour of musician Ryuichi Sakamoto, the former co-founder of pioneering Japanese electronic music group Yellow Magic Orchestra. As important to Japanese music culture as Bowie was to British audiences, Oshima saw his photograph in a book and believed he was right for the role. He’d never acted before but knew Oshima’s work and persuaded the director to let him compose the film’s celebrated score.

Meanwhile, Bowie had been busy as the lead in Alan Clarke’s BBC adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s Baal (1982), recording “Under Pressure” with Queen, and had just completed filming on Tony Scott’s The Hunger (1983) when he was given three weeks notice to join the production in Rarotonga, New Zealand, for seven weeks of filming between September and November 1982. The cast included British theatre and TV actor Tom Conti as Lawrence, after Jeremy Irons allegedly turned down the role, and Takeshi Kitano, then known as a stand-up comedian, playing Sergeant Hara. Kitano would later flourish as a director after his debut with Violent Cop (1989).

Oshima worked quickly, filming more or less in sequence and opting for one or two takes per set up. Bowie noted that he hardly featured any of the elaborate exterior set for the POW camp into his shots (although the finished film slightly contradicts this). He and Conti were left to their own devices and Oshima gave them scant direction, preferring to concentrate on the performances of his Japanese cast. Prints of the dailies were shipped to Oshima’s editor in Japan and, when shooting was over in November, she had a rough cut ready within four days. What emerged the following year at Cannes was perhaps Oshima’s most European film, in a sense. Often deemed a star vehicle assigned to Bowie and Sakamoto or compared to David Lean’s epic war film The Bridge on the River Kwai (1962), despite its subversion of Lean’s prisoner of war motifs, it was a more subtle and complex film.

The powerful opening, written specifically for the film, where Hara (Takeshi Kitano) interrogates a guard of Korean descent suspected of raping a Dutch prisoner calls back to Oshima’s interest in Japanese attitudes to Koreans, a prejudice he explored previously in Death by Hanging. Hara becomes enraged when Lawrence (Conti) attempts to intervene in the guard’s attempted suicide. He initially dismisses what the victims have to say and Lawrence’s perspective on the matter, but then finds himself conflicted by Lawrence’s respect for and knowledge of Japanese culture and language and his innate compassion towards the two men. When Yonoi demands to know why Hara didn’t report the matter, he concedes he did it out of mercy.

Hara’s confounded but fascinated by Lawrence as a pragmatic, cautious figure who walks the fine line between the rigid, binary oppositions of Eastern and Western attitudes in the film. Oshima shows us, through the two characters, how the Japanese view themselves and are viewed by the British in the film and vice versa. Hara is brutal and unforgiving but, as the film progresses, it’s clear that Lawrence’s philosophy affects him and, introspectively, he becomes, as Tony Rayns describes it, “the Japanese everyman in a way that his commanding officer Captain Yonoi does not.” From the outset, the two central performances from Tom Conti and Takeshi Kitano glue the film together and it would be a lesser film without them.

While Oshima uses Hara, Lawrence, Yonoi (Sakamoto) and Celliers (Bowie) to represent this clash of cultures and attitudes, he also explores Lawrence’s class ridden antagonism with the snobbish but patriotic Major Hicksley (Jack Thompson). Hicksley’s blindness to the cultural differences in the camp, that Lawrence sensitively attempts to interpret, precipitate a crisis that breaks Yonoi’s own faith in Japanese ideology in the final act of the film. There, in a desperate attempt to riddle out prisoners with knowledge of Allied armaments and expertise, Yonoi drags all the inmates onto parade, even those barely able to walk from sick bay. Oshima saw Yonoi as a “person with a strong sense of the aesthetic… for him the soldier must always be beautiful, must live beautifully and die beautifully. For him, the prisoners of war are almost unbearable… and yet these unbearable ones are alive.” They dishonour themselves because, as he sees it, the prisoners are not just physically sick but suffering a spiritual malaise.

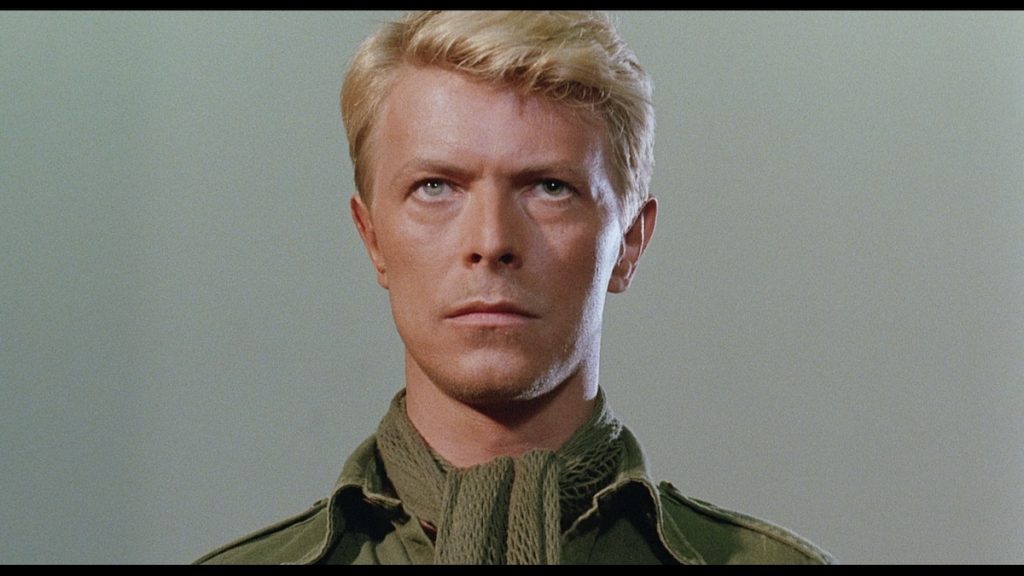

Gregory Desilet offers that the opening scene also marks out “the Japanese cultural contempt — at the time of World War II — for homosexuality” and this is then compounded when Yonoi encounters Celliers at the court martial and in the POW camp. Rayns makes an interesting observation that Oshima wanted to explore his own “latent gay feelings” with Merry Christmas after he’d read the book and detected a homoerotic undercurrent in the story. In the court martial scene, when we first see Celliers, Oshima’s camera tracks towards Yonoi, who is flustered but clearly admires not only Celliers’ defiant attitude but also his Caucasian appearance, reflecting an aspect of the Gaijin complex in Japanese society, in its fascination with the West after it emerged from isolationism, where as a blonde, blue-eyed man he is, to Yonoi, the pure soldier he recognises in himself. However, Masao Miyoshi sees Yonoi as simply in thrall to the Western ideal represented by Celliers, as an egregious display of the director’s “unconcealed aspiration and admiration for Europe and Europeans.” As an international co-production, Oshima’s film could be accused of this but the director’s work has always been about bringing in outside influences.

Hara reduces all British men to weak homosexuals after Lawrence asks him to protect the Dutch soldier from the men in the camp. Lawrence offers another interpretation: “war makes friendship among men stronger. But that hardly means all soldiers become homosexual.” This is reinforced in a later scene, where Celliers breaks Lawrence out of confinement and refuses to fight Yonoi. When Yonoi yields and spares Celliers, Lawrence cannily notes: “I think he’s taken quite a shine to you.” He’s certainly becoming obsessed with Celliers by this point in the film but that obsession seems to go beyond a physical infatuation.

Oshima’s take on this, from Paul Joyce’s interview on the disc, is that it continues the theme of eroticism in his work, where “it’s an eroticism that emerges in a physical relationship where there is no physical contact between two individuals who are of the same sex, and who are also each other’s enemies.” Yonoi is also in love with the myth of Celliers, the ‘soldier’s soldier’. Erroneously, he sees Celliers as someone who can replace Hicksley, to instil honour and discipline in the camp. Oshima returned to similar themes in his last film, Gohatto (1999). This was a period film about homosexuality in the Shinsengumi, the military government’s special police force, during the samurai era in the mid-19th-century.

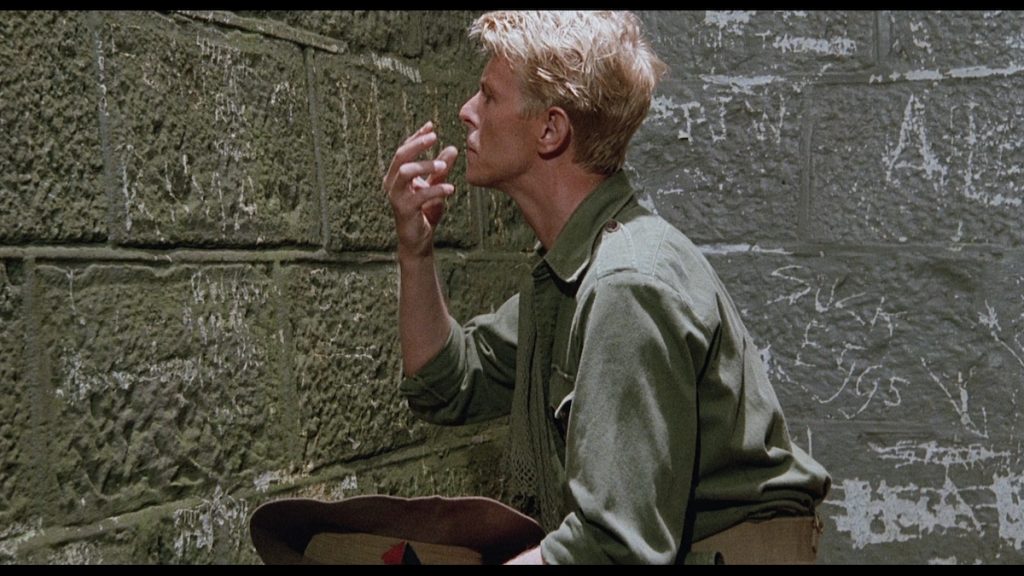

Celliers’ challenge to Yonoi’s perfectionism and nationalism is heightened by the casting of Bowie and Sakamoto. Bowie’s own otherness, his challenging, ever-changing personas and appearances as a performer/singer, is bound up within Celliers. In effect, Celliers is a visual link to Bowie’s blonde-haired, tanned avatar that would emerge with Bowie’s Let’s Dance album during Merry Christmas’ release in 1983. Yonoi’s appearance, where Sakamoto’s face is exquisitely made up, suggests androgyny and a pop career in Japan to match Bowie’s. Both are non-actors required to ‘perform’ and Bowie, with Mayersberg’s script offering him one of his best screen performances, effectively uses his mime training in the court-martial prison cell sequence, while Sakamoto evokes his character’s repressed desire, at breaking point, in a series of perfectly lit tableaux.

Key to the film’s exploration of honour and spirituality is the sense that both Celliers and Yonoi are haunted men. Events in the past have ingrained a sense of betrayal in one and shame in the other. For Celliers, it is the betrayal of a younger, disabled brother, and his exploits as a guerilla fighter offer some form of purgative to that guilt. Yonoi has become commander of the camp as a punishment, a humiliation, after February 1936’s failed military coup in Tokyo. Posted to Manchuria, he was unable to participate with his fellow “shining young officers” who have all since been executed.

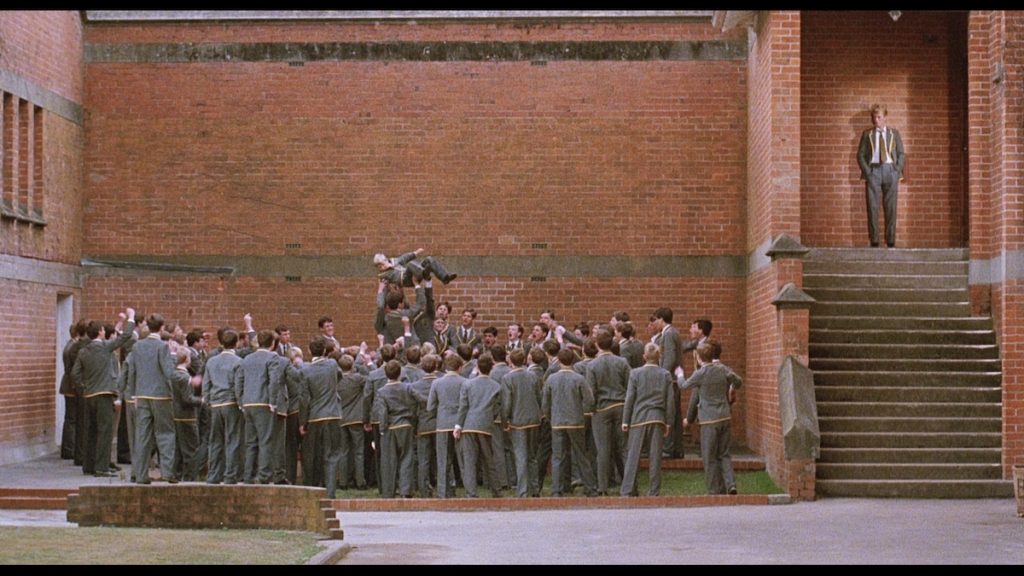

Bowie relates Celliers’ guilt through flashbacks. Contrary to other reviews and analysis, the flashbacks are not meant to be set in England and, given that van der Post was South African, he’s represented as such by Celliers and Lawrence in the film, that Bowie performs Celliers as a South African serving in the British Army, it’s clear they’re set during a South African childhood at boarding school. Granted, the flashbacks are awkwardly staged but they convey the guilt that underpins Celliers’ do-or-die philosophy, the “evil spirit” that disables Yonoi’s maintenance of a thousand-year-old bushido code of honour. Yonoi’s shame is only briefly mentioned, in a conversation with Lawrence and, perhaps, a flashback to Tokyo might have reinforced this as it’s not easy picking up on the impact of shame, as Mayersberg notes in Joyce’s documentary, ingrained within the Japanese psyche.

The film is a brutal picture of internment and the Japanese treatment of Allied prisoners but it’s an uneven film in places. The flashbacks to Celliers and his brother don’t particularly sit well within the film and Oshima doesn’t quite communicate to us the Japanese social and cultural traditions that underpin the relationships in the film. However, using Lawrence and Hara to reveal the dehumanising effects of war on the class-bound British and code-bound Japanese (with their “bloody awful stinking gods”) still has great resonance.

Hara and Lawrence remain the emotional core of the story while Celliers’ and Lawrence’s “acts of resistance, coupled with acts of acknowledgement and respect” make Yonoi face the enemy on very different terms. Yonoi taking a lock of Cellier’s hair and creating a shrine to the dead officer is a very moving coda to the film as is Lawrence’s summation of the whole situation to Hara, awaiting his execution: “You are the victim of men who think they are right… just as one day you and Captain Yonoi believed absolutely that you were right. And the truth is, of course, that nobody is right…”

UK • NEW ZEALAND • JAPAN | 1983 | 123 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • JAPANESE

director: Nagisa Ōshima.

writers: Nagisa Ōshima & Paul Mayersberg (based on ‘The Seed and the Sower’ by Sir Laurens van der Post.)

starring: David Bowie, Tom Conti, Ryuichi Sakamoto Takeshi & Jack Thompson.

I am indebted to the following articles and books:

Maureen Turim, The Films of Oshima Nagisa: Images of a Japanese Iconoclast (University of California Press, 1998) • Robert Niemi, 100 Great War Movies: The Real History Behind the Films (ABC-CLIO, 2018) • Dennis Lim, ‘Nagisa Oshima, Iconoclastic Filmmaker, Dies at 80’, (New York Times, 15 January 2013) • Cathy Brennan, ‘Stories from the set: In the Realm of the Senses’, (One Room With A View, 14 September 2016) • Katsue Tomiyama and Ted Goossen, ‘Nagisa Oshima on In the Realm of the Senses’, (Criterion Collection, The Current, 30 April 2009) • Chuck Stephens, ‘Lawrence of Shinjuku: Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence’, (Criterion Collection, The Current, 28 September 2010) • Roger Pulvers, ‘Nagisa Oshima: You have to tell the truth about your country, whatever it is’, (The Japan Times, 9 January 2016) • Richard Combs, ‘A Lotus Rising: Paul Mayersberg on Nagisa Oshima’, and ‘Mad Dogs and Englishmen: interviews with Jeremy Thomas and Nicolas Roeg’, The Monthly Film Bulletin (BFI, Volume 50, Number 588, January 1983) • Joan Mellen, BFI Film Classics: In the Realm of the Senses (BFI, 2004) • Dinita Smith, ‘Master Storyteller or master deceiver?’, (New York Times, 2 August 2002) • Roger Bourke, Prisoners of the Japanese: Literary Imagination and the Prisoner-of-war Experience, (Univ. of Queensland Press, 2006) • Nicholas Pegg, The Complete David Bowie (Titan Books, 2016) • Dylan Jones, Bowie: A Life (Random House, 2017) • Masao Miyoshi, Off Center: Power and Culture Relations Between Japan and the United States (Harvard University Press, 1991) • Gregory Desilet, Screens of Blood: A Critical Approach to Film and Television Violence (McFarland, 2014).