THE CONVERSATION (1974)

A paranoid, secretive surveillance expert has a crisis of conscience when he suspects that the couple he is spying on will be murdered.

A paranoid, secretive surveillance expert has a crisis of conscience when he suspects that the couple he is spying on will be murdered.

Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) can record any conversation in the world. In the fantastic opening shot of The Conversation, our perspective slowly closes in on a couple strolling through a park, engaged in furtive discussion while trying not to be overheard. As a surveillance expert, Caul’s found a way around their attempts to conceal their clandestine meeting: the conversation is recorded.

A powerful business magnate has offered Caul $15,000 (the equivalent of $95,000 today) to capture their words on tape. He couldn’t have approached a more capable person, for Harry Caul is not normal. Considered a pre-eminent talent in his field, he speaks a different language to most. His language is that of microphones, amplifiers, and lavaliers, and most importantly, it’s bolstered by a clinical, strategic indifference. However, as Italo Calvino tells us in Invisible Cities (1972): “There is no language without deceit.” No matter how powerful the technology employed, the truth can always be obscured somehow…

Although Caul succeeds in capturing the conversation, it subsequently becomes an obsession for him. He’s wracked with guilt, not over the nature of his duplicitous profession itself, but by the inherent consequences of his work: no one would pay such a large sum to listen to a conversation if it weren’t for an extremely grave purpose. Once he refuses to hand over the audio recording to his employer, he soon suspects that nefarious figures are following him, that he will be responsible for someone getting hurt again, and that this conspiracy he’s become embroiled in will prove fatal.

As I recently pointed out in my retrospective of Some Like It Hot (1959), Billy Wilder’s body of work from the 1950s would have ranked as an unrivalled streak of brilliance were it not for Alfred Hitchcock’s legendary string of films within the same period. However, in stark contrast, Francis Ford Coppola’s resume in the 1970s is so unprecedentedly brilliant that he had no equal.

Having created some of the greatest films ever made during this period, with masterpieces like The Godfather (1972), The Godfather Part II (1974), and Apocalypse Now (1979), the New Hollywood director practically defined an entire decade of cinema. As a result of such prowess, one of his features went almost entirely unnoticed, and has since fallen into the shadow of his other work: The Conversation. In my opinion, Coppola’s tense psychological thriller ranks as one of the most underrated films of the 1970s.

Like many of Coppola’s best movies, The Conversation is an intense, probing character study. Harry Caul is a meticulous technician, but also a taciturn recluse. He’s a devout Catholic, yet also enthusiastically unscrupulous in his work; employing the most sophisticated form of devious behaviour is a competition in which he excels.

However, it’s this very job that makes him paranoid all the time, constantly questioning whether he can trust those around him. When his girlfriend, Amy (Teri Garr), sings a song, it arouses his suspicions, causing him to interrogate her about where she heard it. He’s apprehensive about letting anyone into his life, anxious that they’ll betray him in some unforeseen way. He reduces himself to an unknowable spectre: “I don’t have any secrets.”

Of course, the troubled lines etched on his brow betray his lie. He’s not just a man with secrets, but one haunted by them. Consequently, everything about him is off-limits. Amy persists in trying to learn something about him, but he becomes defensive and evasive. Harry Caul doesn’t want to be known, seen, watched, or heard. He understands the fate of those who attract attention. He craves to be a ghost, a phantom, a man who exists without personal attachments.

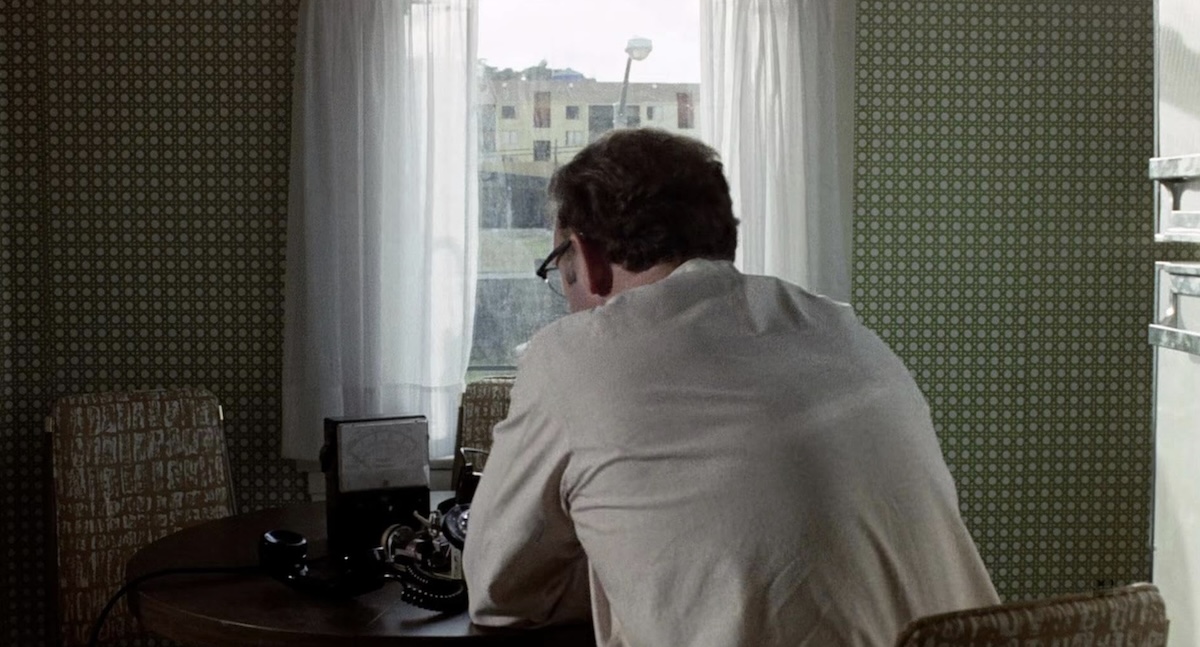

We can see that in his lab work, where he listens to the same tape repeatedly to achieve a clean recording. This isn’t merely isolated work, it’s isolating: he inhabits a different world, trapped by conversations with strangers he’ll never meet. This explains his strive for complete disinterest in the subject matter: “I don’t care what they’re talking about. I just want a nice, fat recording…”

When he senses sinister forces at work, however, he does the very thing he shouldn’t: he becomes preoccupied with the content of their conversation. Understanding their discussion could provide insight into the heart of the mystery, leading him to become utterly fixated on what’s transpiring. The lines between his work and his conscience blur, no matter how hard he tries to keep them separate.

In this respect, Coppola’s film demonstrates a preoccupation with knowledge in a rapidly evolving world of technological possibilities. What you know might get you killed, while what you don’t know leaves you entirely unprotected. His assistant, Stanley (John Cazale), is inquisitive about their target’s conversation out of pure curiosity: “It’s curiosity (…) It’s just goddamn human nature.” As humans, we have a desire to know things, especially what happens around us.

Throughout this, an existentialist theme is present in the film: how do we come to know things? What precisely are our methods of acquiring knowledge? And most importantly of all, can they be trusted? Such was the epistemological uncertainty of the US at the time–and perhaps ever since. After Watergate, the Vietnam War, and even the entire McCarthyism era, the American people felt as though they couldn’t know anything for certain. There was an underlying sense that those in power were lying to them and that their private lives were becoming less and less private.

This atmosphere of nationwide suspicion and incorrigible distrust is mirrored in the surveillance convention. As salesmen hawk their latest spy gadgets, you might wonder: who would buy these things? The answer is people in a society that’s hurtling headlong into complete, sheer paranoia. One salesman assures us that his devices are “not helping crime—it’s helping justice.” Of course, he’s well aware that such technology can never be contained, that the way a machine is designed will not necessarily dictate how it’s used, and that ultimately, the highest bidder rarely has virtuous motives.

A rather comical example of this truth can be found when the group leave the surveillance convention and encounters a reckless driver on their way to the after-party. The off-duty cop calls in the licence plate, but instead of upholding the law, he merely shouts out the driver’s details: his name, height, and address. A technology designed to preserve order is immaturely used to incite fear.

In terms of inciting fear, Harry Caul’s devout Catholicism is no coincidence; after all, who’s a greater expert in surveillance than God himself? The weight of Caul’s religious beliefs burden him heavily, and he grapples with a strong dose of Catholic guilt throughout the story. Much like Harry Caul, God is ever-listening; Caul’s elaborate gadgets are mere attempts to augment his senses and add to his knowledge, making him akin to his Lord and Saviour.

Caul understands, however, that with great power comes an inordinate amount of responsibility. How he wields his genius will define the lives of others—but will it be for the good? This accountability torments him, causing intense distress. “You’re not supposed to feel anything about it,” Meredith (Elizabeth MacRae) tells him. “You’re just supposed to do it.” However, Caul grasps that what he does is no mere trick. In a world that increasingly values information, he knows his work is pivotal in the hands of the powerful.

Coppola’s direction marks him as a master of the medium, demonstrably at the top of his game. His pacing builds the encroaching fear of a nebulous threat: something is coming, but we simply don’t know what, when, or where. The film truly breathes as a result: paranoia takes hold and Caul’s obsession draws us ever closer to the truth. Tension builds impeccably: the ring of a phone, a shadow on a door—it is all pure cinema.

Thankfully, Coppola doesn’t spoon-feed his audience information. Instead, we’re invited to see the world through Harry Caul’s mind. As he feels under a tap, isolates audio, or gives a pen an accusing stare, we view Caul’s surroundings with the same inquisitiveness, fascination, and distrust. We too are overwhelmed by uncertainty, and we pity Caul as even his faith falls victim to his paranoia: he destroys a figurine of the Virgin Mary, convinced it’s bugged. It isn’t—but Caul knows that even the most intimate aspects of one’s life can be violated in the unending pursuit of knowledge.

The film wouldn’t be as engrossing as it is without the massively intelligent use of sound. The conversation that Caul obsesses over loops in his head, becoming part of the non-diegetic soundtrack. It’s become such a potent reality for Caul that it sometimes feels as though he struggles to differentiate between two worlds: the real one, which he avoids at all costs, and the world he’s created with some microphones and a tape deck.

As such, The Conversation is akin to a modern Greek tragedy, suited to an age of technological paranoia, a time where machinery and intelligence advanced at a rate that outstripped one’s ability to keep up. In this respect, the film is also strikingly prescient; nowadays, you can never be sure if you’re being watched, overheard, or traced.

At the film’s end, as Caul rips apart his flat in a bid to find a hidden microphone, you’re probably tempted to ask: why not just move? But that would be to miss the point entirely—he craves knowledge. His obsessive quest to understand the world around him, even at the expense of living a ruinous and lonely life, is the catastrophic character flaw that defines him. The camera pans back and forth as if it were CCTV footage: watching, watching, watching…

Perhaps more than any other of his films, Coppola establishes himself as a singular director with The Conversation, a key figure of New Hollywood cinema. The film shares more in common with European cinema than it does with its American counterparts, exhibiting stylistic similarities to films like Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970). The plot also bears a close resemblance to Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966), in which a photographer believes he’s captured a murder on film.

Even so, Coppola’s film retains a wholly unique feel. Although Star Wars (1977) was such a success that it effectively brought the New Hollywood movement to an end, The Conversation is significant because it showcased an era of American filmmakers intent on creating slow-burning, contemplative cinema. Consequently, it inspired the likes of Brian De Palma’s Blow Out (1982), Oliver Stone’s JFK (1991), Sneakers (1992), and The Lives of Others (2006).

In Invisible Cities, our narrator is approached by a philosopher on a lawn: “Signs form a language, but not the one you think you know.” The same can be said of Harry Caul. With all his technology, it only obscures the truth, driving him further away from it, yet deeper into the recesses of his mind. The more he tries to analyse and record the world around him, the more it serves to isolate him.

In my opinion, The Conversation is one of the greatest films of the 1970s. It shrewdly depicts the issues that will dominate the next 50 years: surveillance, power imbalances, corruption, and the unstoppable march of technological progress. Coppola masterfully conveys these anxieties through a character study filled with visceral thrills, creating a film that will always keep you on the edge of your seat.

USA | 1974 | 113 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Francis Ford Coppola.

starring: Gene Hackman, John Cazale, Allen Garfield, Cindy Williams, Frederic Forrest, Harrison Ford, Teri Garr & Robert Duvall.