THE AVENGERS – ‘Tunnel of Fear’

"Tunnel of Fear" is the 20th episode of the first series of the 1960s British TV series The Avengers, and one of only three known complete series 1 episodes to have survived original broadcast...

"Tunnel of Fear" is the 20th episode of the first series of the 1960s British TV series The Avengers, and one of only three known complete series 1 episodes to have survived original broadcast...

It’s always heartening to hear that material long missing from film and television archives has miraculously turned up. Such was the case when a private collector contacted Kaleidoscope, the classic television organisation, in 2016 and negotiated the sale of approximately 70 items. Among these were episodes of well-known dramas Z Cars, Dr Finlay’s Casebook and Softy, Softly, as well as episodes of comedy programmes Hugh and I, and Here’s Harry.

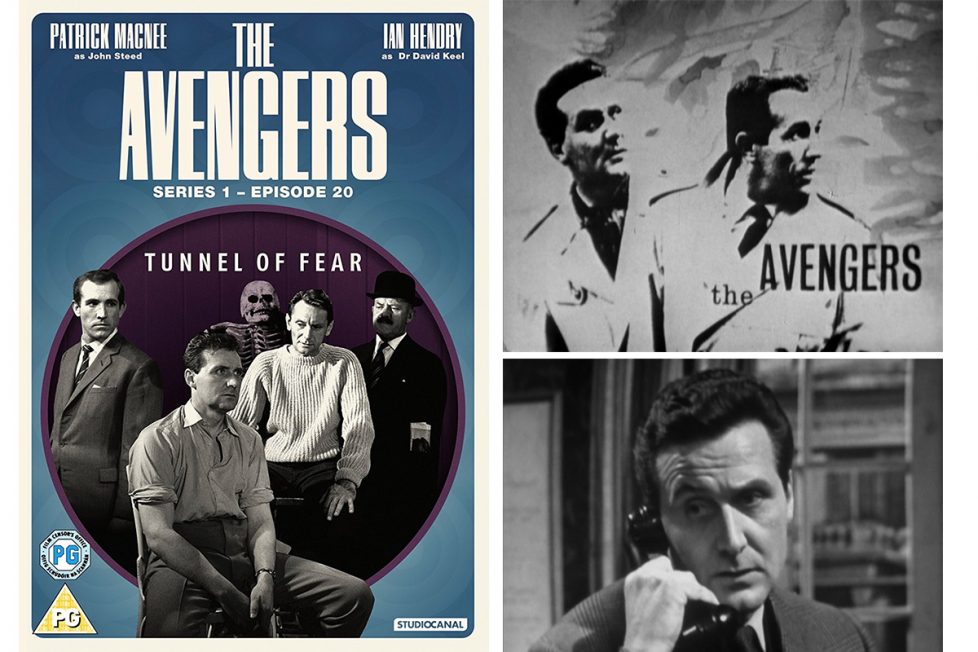

All remarkable recoveries, but the icing on the cake was the return of an early episode of The Avengers, the hugely successful British spy-adventure series that ran between 1961-69. The recovered 16mm black-and-white telerecording of “Tunnel of Fear”, one of the few surviving from the first series, has now been made available by StudioCanal as a standalone DVD release. Before I take a look at the episode itself, it’s worth placing the creation of The Avengers in context and where “Tunnel of Fear” was representative of the early exploits of its original line-up of Dr. David Keel (Ian Hendry) and his sidekick, the mysterious John Steed (Patrick Macnee).

George Dixon had been on his beat at the BBC for 5 years in Dixon of Dock Green when ABC’s procedural drama Police Surgeon debuted in 1960. A short-lived star vehicle for actor Ian Hendry, it featured the moral and ethical dilemmas faced by Notting Hill doctor Geoffrey Brent as he assisted the London Metropolitan Police with Bayswater’s dysfunctional families, disreputable landlords, delinquents, and petty criminals. Yet, out of these humble origins would emerge one of the greatest UK television adventure series ever made, The Avengers.

Created, written, and initially produced by Julian Bond (who had made an initial impact with ATV’s Probation Officer series), many of Police Surgeon’s scripts had been written in consultation with J.J Bernard, the pseudonym of a real police surgeon. A number of factors affected the eventual fate of Police Surgeon and the birth of The Avengers. Although the series gradually gathered decent ratings it wasn’t the big success that ABC had hoped for and several regional ITV companies ditched it from their schedules a number of weeks into transmission. Julian Bond bowed out as producer, the workload having defeated him, and he was replaced by Armchair Mystery Theatre producer Leonard White.

There were also contractual concerns raised by Bernard (Leonard White described it as “a rights problem”, but the reality was an injunction that ABC had to settle out of court), that put the kibosh on Police Surgeon. ABC’s Head of Drama, Sydney Newman, decided to cancel the half-hour drama after 13 episodes. While Newman believed ABC needed to hang on to and find a new series for Hendry, chief executive Howard Thomas wanted Newman to develop an adventure series —“something more light-hearted and sophisticated” than the realism of Police Surgeon —similar to Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man, featuring retired private detective Nick Charles and his wealthy wife Nora, made popular in the 1930s and 1940s with a series of films starring William Powell and Myrna Loy. Hendry is often overlooked in the history of The Avengers, simply by dint of his departure after series 1, and because we don’t have that many episodes to get a thorough sense of his impact as David Keel. But he was a charismatic, dedicated actor, and his contribution to The Avengers shouldn’t be undervalued.

Inspired by Hitchcock’s thriller North By Northwest (1959) and Ian Fleming’s Bond books, Newman, White, and the production team concocted a one-hour drama as a vehicle for Hendry, playing Dr David Keel (a re-development of his original Police Surgeon character), and a second character, played by someone who could share with him the load of the hectic production schedule. This character would be an undercover agent working with Keel: “someone amoral, suave and brainy, who wouldn’t deign to dirty himself by physically fighting, preferring a silenced gun or sword-cane. Sparks would fly between them.” Enter, John Steed.

There are differing claims about who created or wrote the first episodes of The Avengers. Indeed, the title of the series was often credited to Newman, but producer Leonard White recalls that the title was not agreed upon until well into pre-production and scripting and was one he suggested to Newman after poring over a dictionary for inspiration. Brian Clemens, who’d been working on Patrick McGoohan’s spy series Danger Man in 1960, recalled that he and writer Ray Rigby shared the task of writing the first two episodes but both were probably given the original story ideas by the two editors Patrick Bawn and John Bryce. Hendry was also a volatile individual and certainly made his thoughts known about the scripts and the writers and this would necessitate hurried re-writes in rehearsals and during recording.

Joining Hendry and producer Leonard White on the series were a number of Police Surgeon cast and crew, including director Don Leaver and actress Ingrid Hafner (who would play Carol Wilson, Keel’s surgery receptionist). Finally, actor Patrick Macnee was cast in the role of John Steed, the shadowy undercover spy, to whom Keel turns for help in seeking revenge for the murder of his fiancée by a gang of heroin smugglers in the opening episode “Hot Snow”. Although the surviving first act of “Hot Snow” does not feature Steed, it’s clear from the script and other surviving episodes, “Tunnel of Fear” particularly, that Keel and Steed were created as perfect foils for each other.

Patrick Macnee’s acting career in Canada and the US had kept him and his family financially secure for about 8 years, but his divorce in 1956 from his first wife Barbara eventually saw him gravitate back to working in Britain in 1960. When Leonard White called him about The Avengers, Macnee was attempting, successfully at the time, to make it as a documentary producer (in London he was working on The Valiant Years series based on Churchill’s memoirs) rather than an actor. White convinced him it was a part he shouldn’t pass up and it certainly offered better pay, once he’d negotiated a price per episode with a somewhat disgruntled Newman.

Bond was suggested to Macnee as an inspiration to play the character of Steed by director Don Leaver, but Macnee didn’t particularly like the Bond of Fleming’s books and instead chose to use “the veneer of Bond for Steed, without using the core. What I left out were the words ‘licence to kill’. Steed had no licence to kill. All I really had as Steed was this iron will to bring the enemy to book.” Equally, the iconic image of Steed— bowler, Savile Row suits, and brolly— didn’t really emerge until well into the series. The early publicity materials and title sequence, courtesy of a photoshoot in Soho, also show him and Keel sporting the ubiquitous uniform of the private investigator, the trench coat.

Police Surgeon’s successor therefore ushered in a different crime-fighting partnership, but the noirish social realism of that originating series still pervades the first episodes of The Avengers, and the other existing material from the first series—“Hot Snow”, “The Frighteners”, and “Girl on the Trapeze”—tap into a seedier London underworld as well as expand the stories to international criminal activity. “Tunnel of Fear” is no exception but it also shows progress towards a more familiar, wittier vision of The Avengers.

“The Frighteners” and “Girl on the Trapeze”, the only complete episodes we’ve had until now, are good examples of what the series was achieving overall in its narrative form and style during that formative first year. Propelled by the work of directors Don Leaver and Peter Hammond, the majority of stories stem from Keel’s profession as a GP and his partnership with Steed. Make no mistake, The Avengers was designed as a star vehicle for Hendry and Dennis Spooner’s “Girl on the Trapeze” indicates well how the Keel solo episodes worked within the structure of the series.

Spooner’s script also inaugurates an ongoing and developing trope for The Avengers as a whole, in that the story uses an atypical circus setting for a tale of Communist defections. Outlandish set-ups would increasingly start to drive the narratives of later episodes, particularly in the filmed series, but here it’s the exception to the rule and was an attempt by producer Leonard White to shake up the rather dull formula where Keel would bring various London based street gangs, blackmailers, and crooks to book.

Later episodes in series 1 also moved away from these stock situations and took in deadly viruses, industrial saboteurs, and political assassinations, as well as the use of more international locations. Patrick Macnee’s John Steed character didn’t feature so prominently and was very much brought into situations by Keel himself. It’s only gradually that Steed became more central to the series. After its first 26 episodes a number of events also conspired to retrofit the series. An Equity strike held up production and during the hiatus Hendry took up the offer to pursue a film career. By the time production began on the second run of 26 episodes, Hendry was gone and Patrick Macnee was propelled into the lead role as John Steed.

As I’ve noted, not many episodes of the original series of The Avengers survived the accepted archiving practices of the day, which was usually to discard any recordings held once their commercial value had been exhausted as the tape they were recorded on was expensive and could be reused. Film recordings of Part 1 of “Hot Snow” and complete episodes “Girl on the Trapeze” and “The Frighteners”, were discovered in the UCLA Library of California back in 2001 having been donated to the Library by MGM.

These only existed because the series, like so many British dramas of the period, was sold internationally. Presumably film recordings had been forwarded to other countries including the US, as was standard, but not returned to ABC after transmission. “Tunnel of Fear” may well have made its way to the US in similar circumstances but was acquired by a dealer in the 1990s who sold it on to a British collector. He retained it in an unmarked can for many years and it was uncovered when he was cataloguing his film library. Thus, once he knew what he had, contact was made with Kaleidoscope.

Although we’ve had reconstructions and audio versions in recent years, what’s exciting about “Tunnel of Fear”, the 20th episode of the first series, transmitted on 5 August 1961, is that it provides us with a proper look at John Steed’s status in the series and demonstrates narratively and visually how the format was shifting away from the formula carried over from Police Surgeon.

Written by former clapperboard operator and cameraman John Kruse, the episode trades on his established qualities as a scriptwriter. He’d written several short stories, one of which was the basis for Cy Endfield’s superb thriller Hell Drivers (1957), and contributed to many TV series, including Armchair Theatre, The Human Jungle, and The Saint. “Tunnel of Fear” acknowledges the influence of contemporary Cold War espionage scandals, such as the Cambridge Five and the Portland Down spy ring, by showing a former British serviceman, brainwashed in Korea (shades of The Manchurian Candidate), passing secrets to the enemy within the confines of a ghost train ride at the Belair fun fair in Southend.

Like “Girl on a Trapeze”, where it makes much of its circus surroundings by mixing them together with a Cold War espionage plot, “Tunnel of Fear” is not at all far from the template —the spy story writ with surreal and extraordinary touches —that The Avengers would successfully develop in its later incarnations. The hustle and bustle of the fun fair and the lives of its employees are conveyed very well and offer a different kind of backdrop to the espionage tale at its heart, adding a flavour of Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock to the proceedings. Kruse’s depiction of working class characters and situations adheres to Newman’s determination to reflect ordinary lives in the drama he was commissioning at ABC, the backdrop of a seedy underworld seen in Police Surgeon and in earlier episodes of The Avengers. There are some very lively characters for Keel and Steed to encounter when they meet Harry Black (an excellent Anthony Bate, last minute replacement for actor Murray Hayne), on the run from prison after being framed for the theft of the fair’s takings, and agree to help him.

The shrimp seller and Harry’s mum Mary (Doris Rogers), Madame Zenobia (Hazel Coppen) a cynical clairvoyant who “can’t even order a pint without making a riddle of it”, the violently jealous ghost train owner Maxie Lardner (Stanley Platts) and the creepy hypnotist Billy Flowers (Douglas Rye) are all vividly and richly brought to life as Keel sets out to help Harry recreate the original crime to help him uncover the frame up (although we never really find out why Harry was framed by his army buddy Jack Wickram). Another aspect to Harry’s character is his relationship with girlfriend Claire (Miranda Connell), whose circumstances have dramatically changed after his imprisonment. When her infidelity and the resulting illegitimate child are revealed, this adds much more realism to her character and the exchanges between her, Harry and his mother.

When Steed goes undercover as a fairground barker, flirting madly and displaying a somewhat less than gentlemanly comportment with the belly dancers he’s promoting, this episode provides us with a better view of the prototype Steed. Macnee, obviously relishing the lion’s share of the script, is already injecting the character with many of his well known traits— that twinkle in the eye, the rakish charm and the expert bluff —and excels in this story. Ironically, given the class distinctions in the episode, our first sight of the villain Jack Wickram (John Salew), right at the start of the episode, depicts him aping the future Steed, dressed in neat suit, bowler and carrying a brolly. We also get to see one of Steed’s bosses, One-Ten (Douglas Muir), and the coded communications between them as they ascertain Wickram’s involvement in the wire tap at the fun fair. There’s also a chance to encounter Steed’s canine sidekick, Puppy (played by Juno, trainer Barbara Woodhouse’s 11-year-old Great Dane).

Hendry does get his fair share of the limelight. The opening act, set in his surgery when the injured Harry Black arrives, provides evidence of Keel’s humanitarianism. He decides to help Black rather than turn him over to the police, treats his wounds and works in collaboration with Steed to investigate Harry’s crime. When Keel takes Harry through a recreation of the robbery, the two handed scene between Hendry and Bate culminates with Harry’s sudden and manic recollection to Keel that Billy Flowers was with him on the job. The final act, a stand off between Wickram, Steed and Keel also evidences the mutual trust between Steed and Keel. Keel invests in Steed’s ‘bluff’ and the pay off is an appropriately wry retort when Steed offers him a cigarette, “er, no, thanks. I’m thinking of giving it up.”

While director Guy Verney keeps the episode on a tight rein, like his fellow directors on early episodes of The Avengers he pushes to get some fluid camera moves into the mix, despite the impracticality of moving the tank like cameras through the sets, and uses the fun fair to cook up some Expressionistic visuals using shadows and silhouettes. The sets, designed by Terry Green and James Goddard, range from the intimate confines of Keel’s surgery to the expansive and atmospheric fun fair, complete with tents, stalls, ghost train and plenty of extras bringing it to life.

Overall, this release is a very welcome and rare opportunity to experience the earliest incarnation of the The Avengers. It’s clear that elements of the show that would become central to its later evolution were already in place in 1961 but the main appeal of “Tunnel of Fear” is the centre-stage dynamic between Keel and Steed, coupled with Hendry and Macnee’s performances and a production that enjoys testing the limits of what could be achieved in the confines of ABC Teddington’s Studio 2.

StudioCanal’s presentation of the episode is acceptable given its age and condition. I’m not privy to how much work was done to clean up and restore the episode but there are a few instances of instability, dirt, and scratches. But it’s perfectly watchable. There are several special features worth mentioning:

I am indebted to the following volumes for background information: