Takashi Ishii: 4 Tales of Nami (1992-94)

A collection of four films from Japanese director Takashi Ishii.

A collection of four films from Japanese director Takashi Ishii.

Third Window Films continue their mission to disseminate important though underseen Japanese cinema with an excellent introduction to the works of Takashi Ishii. This box set showcases four concurrent early films key to the development of an auteur known mainly for contentious content. While poetically nuanced with rare moments of perfect beauty, they are unapologetically confrontational and transgressive with plenty of potential triggers. Although shot on shoestring budgets, each film drips with stylistic confidence while dealing with difficult subjects relating to psychological, physical, and sexual trauma. Unavoidably, the following reviews contain a discussion of such themes. So, if that bothers you, consider this fair warning and perhaps turn back now. Anyone with an interest in Japanese manga and live-action film adaptations that push the envelope, do read on if you’re feeling robust.

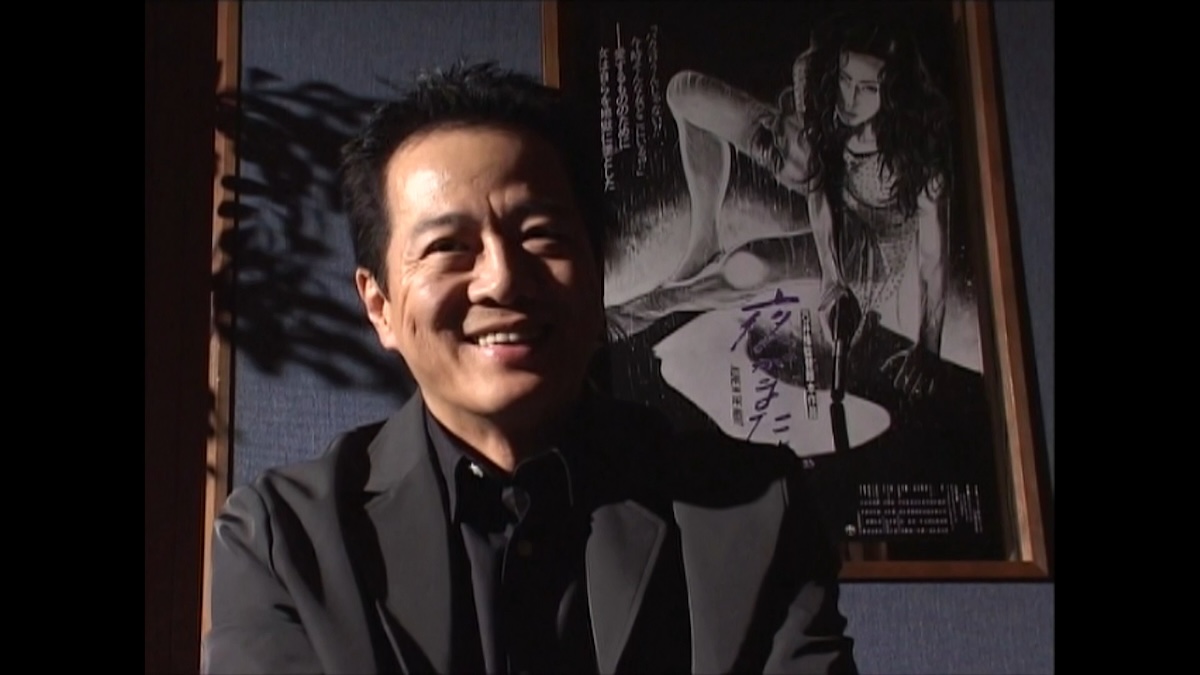

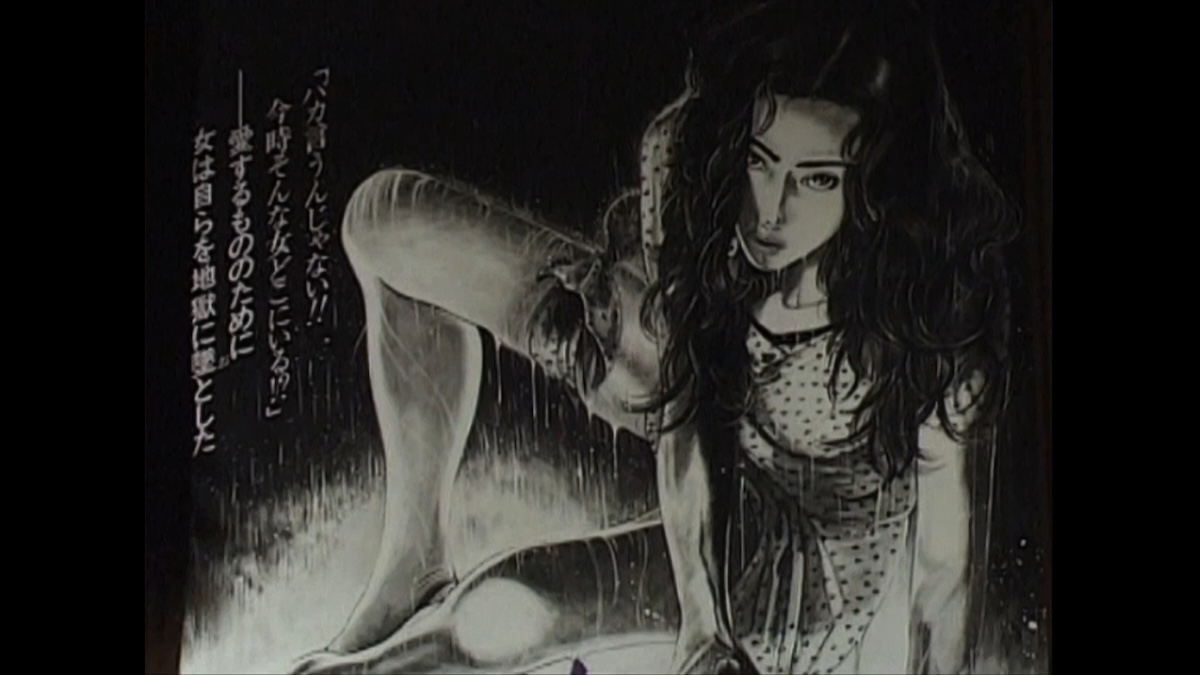

Apparently, Takashi Ishii began working in films as a stagehand and production assistant but found the soil floors of large studios and fresh dust from set construction seriously aggravated his asthma. Putting that career on hold, he turned his hand to manga throughout the 1970s and proved to have a deft hand for illustration. By the mid-1980s he had a solid fan base and a back catalogue of what were effectively ready-to-go scripts and storyboards. He worked on several titles but is best known for his uncompromising Angel Guts / Tōshi no harawata series featuring a recurring protagonist named Nami.

However, she’s a different woman in each tale, perhaps with a shared spirit and, yes, there is the merest tantalising hint of a strange or supernatural element. Perhaps not enough to draw any close comparisons with Tomie, but I’m sure fellow manga maestro, Junji Ito, would’ve been aware of Ishii’s work, which also extrapolates recognisable societal structures until they become terrifying. Like Tomie, Nami is trapped in the endless cycle of violence perpetrated upon women by brutal men but will always push through pain, shame, and psychological strife to prevail, finally shedding the mantle of victimhood. Also, like Tomie, she may find some kind of closure, but never her ‘happily ever after’.

Takashi Ishii has avoided demystifying his multi-faceted character of Nami, who is always the same yet subtly different and never portrayed on-screen by the same actress twice. He has said that she represents an everywoman who suffers at the hands of her boss, yakuza handler, her family, her boyfriend, and so on and is “a protestation against the submission imposed upon women.”

Takashi Ishii quickly became notorious as an early purveyor of gekiga / gekiga and, in Japan, is recognised as one of the artists instrumental in steering this adult-orientated sub-genre of manga toward more graphic representations of sexualised violence. His stories tended to include more extreme set-pieces featuring cycles of rape and revenge that play out against a sleazy underworld backdrop amid dingy urban decay. His graphic works remain relatively obscure in the English-language market where they are often reviled and fall foul of the censors. The first translations of his manga only began appearing in the early 21st century, decades after their publication in Japan where they are received as visually dynamic and dramatic works of emotive fiction for mature readers.

Angel Guts: High School Co-Ed / Jōkōsei tenshi no harawata (1978) was the first of Ishii’s gekiga featuring Nami to be filmed though with no direct involvement from the author. Toshiharu Ikeda and Ryūsaku Shinsui collaborated on adapting the original manga and Chūsei Sone directed. From the few reviews, it seems to be generally dismissed as a nasty piece of exploitation with no likeable characters featuring a teenage biker gang who, like Alex’s droogs in A Clockwork Orange (1971), numb their dissatisfaction and sense of failure with ultraviolence and gang rape, here focusing on schoolgirls including the titular co-ed, Nami. It is the first in what became a six-film franchise of which Takashi Ishii would later take full control, making his directorial debut with the fifth instalment, Angel Guts: Red Vertigo / Tōshi no harawata akai memai (1988), also helming the final chapter Angel Guts: Red Flash / Tōshi no harawata akai senkō (1994), added a few years later and included in this box set.

His films stand astride exploitation and pornography without sitting comfortably in either category. The bravura performances and directorial flair eschew categorisation as mere exploitation and although there’s some nudity presented solely for aesthetics, the often-discomforting sex scenes are too integral to the intricate narratives to be easily dismissed as purely pornographic.

The best way to approach them is as hard-hitting psychological thrillers in the realm of Dark Noir. If produced in the USA they’d hover somewhere between raunchy mainstream Hollywood thrillers in the vein of Brian De Palma’s Body Double (1984), Adrian Lyne’s Fatal Attraction (1987), and Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct (1992), and the harsher indie films like Abel Ferrara’s Ms.45 (1981) and the No Wave Cinema of Transgression coming out of New York in the early-’80s from punk filmmakers including Beth B, Richard Kern, Lydia Lunch, and Nick Zedd. Short films like The Right Side of My Brain (1985) and Fingered (1986) zoomed in on abusive, sometimes murderous, relationships between damaged individuals as a fractal glimpse of a broader societal malaise.

Abuse and how past trauma shapes Ishii’s characters can be read metaphorically to represent broader socio-political national issues such as the economic exploitation of the underclass during and in the aftermath of Japan’s post-war bubble economy; the pre-war rule by an oppressive Imperialist regime and the American occupation that followed the traumas of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; and of course, the more explicit gendered power play and inequality in society.

However, the films of Takashi Ishii are considered to be roman-porno films and were produced and released as such by Nikkatsu. No, it’s nothing to do with Caligula (1979). The term stems from ‘kino-roman’, which is a type of script treatment written as prose rather than in standard screenplay format. Here, it’s taken to mean that the ‘porno’ film has a novelistic approach to its narrative, telling a complex story with a proper plot. I have also read that ‘roman-porno‘ refers to ‘romantic’ sex films but, having now seen a few, I think that’s less likely.

If they were Italian, and made a decade earlier, they’d be considered among the better gialli, with similar character types, puzzle plots, sex, and violence, and often uncomfortable set pieces that trigger an empathic fight-or-flight response in the viewer. They will certainly appeal to fans of the giallo genre and perhaps they should have a different term to describe them. As giallo is the Italian word for ‘yellow’, I would suggest Japanese gialli be labelled akai meaning ‘red’ as the word crops up in numerous titles of similar films and is certainly a recurring motif in those of Ishii.

Also, like gialli, the distributors’ requirements included the number of nude scenes with a stipulated minimum screen-time and the desired body-count. On the plus side, such films were made quickly and cheaply so, if the sex and violence boxes were ticked, the director had almost complete creative freedom in all other areas. Hence, Italian pulp cinema of the 1970s became a testing ground for exciting new writers and directors, producing more than its fair share of innovative and stylistically bold films. Plus, plenty of exploitative trash, too.

Likewise, the contemporaneous Japanese market produced lots of undistinguished, or plain nasty, roman-pornos but there were also outstanding offerings that challenged cinematic conventions. Several of Takashi Ishii’s audacious akai are cited as both defining and defying the genre.

The early films presented here confirm Takashi Ishii as a singular auteur working through many recurring themes and with distinctive motifs such as the colour red, neon light, deep noirish contrasts, sex, blood, and beautiful women. It has been said that he’s only happy when it rains because he uses it as a metaphor for human emotions. If there isn’t a natural rainstorm, he will suggest it through the use of foley. Its shimmer gives form to the darkness of night and renders the invisible visible. Just as his stories and the actors’ performances render invisible emotions. Emotions, like water, can refresh or overwhelm, buoy us up or drown us.

To him, water and emotions are what connect us, physically and spiritually. Biologically speaking, we are mostly water—it’s in our blood, sweat, and tears. It flows through the natural world, falls as rain, runs in the rivers to fill the seas, and evaporates into the air, continuing that endless life-bringing cycle. Nami is seeking similar connections – to her true self, to others, to the world. Perhaps that’s why her name suggests the Japanese word for wave, as in tsunami, along with the ceaseless, untameable tide.

Nami, the wife of an estate agent, begins an affair with a 22-year-old that leads to an ill-conceived plot to kill her husband.

If approaching the films in this box set chronologically, we begin with the weakest and most problematic of the quartet, though it remains visually striking and there are moments that may resonate with fans of cult cinema. The opening is perhaps too subtle for its own good, as we are privy to the dream of Hirano (Masatoshi Nagase), a young man sleeping on a train. The woman and a young boy in the same carriage are projections of his mother and himself as a child, but with the notable absence of a father figure. This is an indicator of the subtlety that Ishii layers under the surface—the sort of thing one might look for in European arthouse cinema, but may miss in films dismissed as violent Japanese ‘porno’. It’s a sort of Freudian peek into his juvenile, mother-obsessed psyche, which will soon reveal itself in a plot that deliberately deploys archetypes from Oedipus Rex, the Classical Greek tragedy by Sophocles.

Hirano alights at a station, wandering along several platforms before picking an exit at random where he literally bumps into a woman (Shinobu Ôtake), nearly knocking her off her feet. From the rapid succession of cuts and close-ups of their reactions, we know the woman, who we will learn is called Nami, made an impression on the young man and maybe vice versa. She opens a red umbrella and trots off into a torrential downpour. The man follows her to the estate agents she runs with her husband, Hideki (Hideo Murota).

Hirano then proceeds to inveigle himself into Nami’s life, first as a potential tenant and then as a trainee estate agent. It’s when she goes to check on him at one of the vacant properties that he forces himself on her. The rape is clumsy and frenzied. Immediately after, he breaks down in tears. Unexpectedly, Nami then pities the man who is many years her junior and takes him to the bedroom where she shows him how a man and woman should treat each other. That she forgives her deeply disturbed attacker and then embarks on a consensual affair in a vain attempt to ‘save’ him, is a shocking development that is definitely not politically correct. This sex scene is inventively shot with the thin bedsheets draping their bodies like a biomorphic kinetic sculpture. It’s interesting but not all that erotic, and those expecting what we call pornography today will feel short-changed, because that’s not what the films of Ishii are about.

However, unlike the other three films presented here, Takashi Ishii’s script is not based on one of his own manga but on a ‘true-crime’ novel by Bo Nishimura inspired by a contemporary murder case. Just like gialli based on real crimes, like The Pyjama Girl Case (1977), it’s hard to find fun in a sordid story that echoes the sad deaths of real people. At times it seems nothing more than watching the lives of dim and damaged people unravel due to their terrible choices as a series of misunderstandings lead to a rather sad conclusion.

I did enjoy the homage to Repo Man (1984) when a drunken Hideki gives a somewhat lame spiel about how to be a good estate agent while being driven home by Hirano. There’s also a messy fight for survival in the cramped confines of a hotel bathroom where the bloody impacts of heads against vitrified ceramics and chromed taps are convincingly brutal and wince-worthy. For the most part, though, the scenes are protracted and ponderous, allowing the viewer time to interpret the complicated emotional subtext between dialogue that the key cast of three make good use of. Shinobu Ôtake is excellent as an older Nami who navigates some complex emotional transitions. She convinces us of the depth of her feelings, even when those feelings remain ambiguous. Ultimately, we can’t know what she feels, and we may not fully understand our own responses either.

Thankfully, all three remaining movies are remarkable and indelibly memorable. So don’t be discouraged.

JAPAN | 1992 | 117 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

When the beautiful and mysterious Nami walks into the office of a man who will “do anything for anyone,” he becomes the unwitting accomplice in a plot to murder her abusive yakuza lover.

We meet the next incarnation of Nami (Kimiko Yo) as she submits to Kozo (Jinpachi Nezu), her drugged-up yakuza pimp in the bar he runs. They’re watched from the shadows, with evident homoerotic relish, by Kozo’s right-hand man, Sendo (Kippei Shîna). A very slick set-up of the three-way dynamic at play.

So, the next scene seems incongruous as Nami, using a false name, hires the “professional stand-in services” of Jiro Kurenai (Naoto Takenaka), whom she discovers unconscious on his dormitory floor next to a partly empty bottle of scotch. There’s something decidedly Bukowskian about the scene and, although his poetry and fiction had been appearing in Japanese translation since the early-1980s, books by Charles Bukowski were only becoming popular in the mid-1990s. So, Ishii was feeling the zeitgeist here. However, Japanese audiences were mainly introduced to Bukowski’s works via Marco Ferreri’s controversial adaptation of Tales of Ordinary Madness (1981), which I’d wager made an impact on Ishii.

A “stand-in” is someone who can be hired to do pretty much anything, as an escort, a fixer, a proxy agent, or in this case Nami claims that she just wants someone to show her the sights of Tokyo because a lone woman tourist wouldn’t feel safe in an unfamiliar city. The montage of the pair enjoying a rollercoaster ride, watching the peaceful belugas in the aquarium, and enjoying the lively street food culture and abundant booze is a pleasant diversion that reveals the more human sides of both of them. However, when the escort sees the drunken Nami safely back to her hotel and leaves her alone in her room, we see she’s been faking all along. Nami is instantly lucid and makes a phone call to Kozo.

As I hope these films will be finding a fresh audience, I’m not giving too much away, but Nami, in classic femme fatale mode, has executed an elaborate plot to frame Jiro by placing him at the scene. She even had him sign in at the hotel desk for her. Hereon in, things get delightfully complicated. We learn that Jiro was once known as Tetsuro Muraki, introducing us to another recurring character that appears in most Nami stories. His relationships with her are often ambiguous, but usually, he’s a catalyst for Nami’s redemption.

When Muraki turns up the next morning to collect his payment from Nami, he finds her gone, leaving no trace except a terse note and Kozo’s corpse. How can he fix such a situation? There may not seem to be much comedy potential here, but there is a delightfully dark humour running through the far superior Night in Nude that was sorely lacking in Original Sin. Muraki crams the body in a large suitcase, packed with dry ice which steams conspicuously, and sets off to return the “left luggage” to Nami.

I was reminded of a few punky French thrillers like Claude Miller’s Deadly Circuit / Mortelle Randonnée (1983) and Luc Besson’s Subway (1985), but there’s also a much harder edge than either of those examples. There’s also a delirious body-horror sequence, with some great prosthetics courtesy of Tomoo Haraguchi, involving the slow phallic insertion of a pistol into a man’s cranium that wouldn’t be out of place in a David Cronenberg movie.

It doesn’t take long before the furious Sendo tracks down Muraki and gets carried away while questioning him with his fists. It’s one hell of a protracted beating and the performances are outstanding, with Naoto Takenaka eliciting pathos and Kippei Shîna absolutely terrifying in his breakthrough role. It also showcases Ishii’s skill, shooting the scene in one take, with Muraki disappearing from the frame for the convincing facial injury prosthetics to be applied, in real time, as he accumulates realistic damage that’ll stay with him. The practical logistics are mind-boggling.

The long, single take is one of Ishii’s trademarks that grants the actors room to delve deep and convey subtleties that would be lost between edits. In this particular scene, the effect is frighteningly visceral in its immediacy, but the extended takes can be mesmerising and emotionally immersive. This is one of the reasons many of the same faces crop up in Ishii’s movies—actors are eager to work with him despite the many challenging hardships and punishing schedules, because he understands the craft and provides plentiful opportunities to showcase their chops. It’s usually difficult to pick a stand-out performance because they’re all top-notch. By all accounts, he’s an actor’s director. That said, the crew also step up for him and certainly cinematographer Yasushi Sasakibara achieves stunning results here within the budgetary and time constraints.

A Night in Nude won a special international director’s prize at the 1994 Sundance Film Festival, which came with a handsome cheque that the filmmaker must spend on improving a future production of their choice. He would use the money to part-fund his next two movies, enabling them to be shot on 35mm rather than the 16mm budgeted for by Nikkatsu studios, who were winding down their roman-porno line at the time.

JAPAN | 1993 | 110 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

Nami, a magazine designer agrees to step-in as cameraman during a porn shoot, but the brutal rape scene brings back distant memories and puzzling things start happening to her.

Here we have a younger version of Nami (Maiko Kawakami) working as a graphic designer for a magazine publisher when she’s offered some overtime as the stills photographer for a rape fantasy porn shoot in an abandoned warehouse. However, the scene is uncomfortably convincing and, while snapping away, reality fractures, and she sees herself in place of the victim. The writer of the scene, this film’s version of Muraki (Jinpachi Nezu), noticing her distress, offers her a hand, but she sees him instead as a shadowy figure from her troubled past.

She seeks solace with her bar manager girlfriend, Chihiro (Noriko Hayami), but later discovers that she has been unfaithful with one of her staff and turns to drink to numb her confusing emotions and dull the disturbing visions that she believes stem from repressed memories. Muraki is also drinking in the bar and when the blind-drunk Nami leaves with a stranger, he sets out to follow her.

What happens next sets up an intricate whodunit mystery—and what exactly was done—when Nami wakes up in a love hotel with the bloody body of a man she doesn’t know lying dead at the bedside. She washes the blood off her hands in the shower and, while gathering her scattered belongings, finds a Hi8 camcorder—remember those?—under a chair. Back at her flat, she reviews the tape and finds evidence of a serial rapist who had attacked at least one other woman. Then, in a dissociative state, she watches the sequence involving her own rape while unconscious.

She’s interrupted by a phone call from a blackmailer who knows where she was and what happened. Immediately suspecting Muraki, she confronts him but is soon convinced of his innocence when he agrees to help her. They then view the entire video together up to the part when a third person enters the hotel room and dispatches her attacker. She now finds herself faced with a new problem: if she hands over the tape to the police, not only will they see her shame, but she would also incriminate her mysterious saviour.

Of the four films in this box set, Red Flash is the closest to a pure giallo/akai with its cleverly convoluted plot, amateur sleuthing, pop psychology, half-remembered phantoms of the past, and the sophisticated set pieces that deliver shocking sex and violence. Like any good giallo, there are enough clues to work out whodunit, but one can’t be too sure until the final, expertly delayed reveal. Even then, Ishii throws in a couple of tiny details that encourage us to question the reality of what we just witnessed and ponder possible alternative explanations long after the end credits roll. A consummate thriller.

JAPAN | 1994 | 87 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

Nami, the wife of a narcotics cop murdered in the line of duty, is surprised to find that her husband has been accused of involvement in organised crime.

As with trends that begin to tire, introducing tropes from an adjacent genre is one way to refresh a formula. Just as the overexposed giallo fused with the poliziotteschi in the mid-1970s, Takashi Ishii melds the akai with the fashion for harsher jitsuroku eiga yakuza thrillers in the final fourth Nami story presented here. Some will say the best is saved for last, but except for Original Sin, the films here are all exceptional for different reasons. This is an achievement for a director with such a distinctive style. None of these films look cheap, which is all the more admirable when one realises that Red Flash and Alone in the Night were both shot back-to-back in 10 days and part-funded out of the director’s own pockets. Apparently, Ishii liked the underlying ennui that lack of sleep elicited in the performances, especially as most of the films were shot at night.

Alone in the Night opens with the sound of rain as Nami (Yui Natsukawa) draws a heart on the handle of the pistol belonging to her husband Mitsuru (Toshiyuki Nagashima) while pleading for him not to go back undercover. The passionate sex between them clarifies their relationship very quickly. Of course, he returns to his undercover assignment, and she never sees him alive again.

It transpires that Mitsuru’s cover was not blown, but he was framed for stealing yakuza drugs with the intention of selling them to a rival clan, and this was the reason for his gangland execution. Shockingly, the police department believes this and suspends their investigation into his death along with Nami’s spousal pension. If that was not bad enough, a group of yakuza hoodlums bust into her apartment to search for the stolen stash. Of course, they find nothing and take out their frustration by gang raping her, leaving her lying among the wreckage of broken furniture, strewn funerary flowers, and a pile of Mitsuru’s ashes. As she regains consciousness, she does something very strange, taking a fragment of Mitsuru’s bones and eating it like a sacrament. She then finds a sharp shard of the shattered urn and cuts her wrists.

Having learned this from Stephen Wei Tung’s Hitman (1998) starring Jet Li, I knew that consuming the ashes of another is thought to be a way of inheriting their strength and bravery. So, it seems Nami does this initially to find the courage to commit suicide. However, she is discovered and saved just in time and will instead direct that courage to finding her husband’s killer and exacting her revenge. Quentin Tarantino must love this film!

To begin with, she intends to just go up to clan boss Ikejima (Minori Terada) in a car park and stab him. Unfortunately, or luckily—depending on one’s perspective—her attempt clashes with a rival clan’s attack, and in the confusion one of Ikejima’s men, Muraki (Jinpachi Nezu, again) intervenes to prevent her but also helps her escape. Her next move is taking a job as a courtesan at one of the top clubs run by the Ikejima clan, where she is recognised by Muraki who again saves her after another failed attempt to assassinate Ikejima. He even goes out of his way to ensure she is allowed to leave. And then rescues her from another attempted suicide. Nami has become the feminine embodiment of the common ‘man-with-nothing-to-lose’ stock character—when someone is not afraid to die, or even wants to, then they can become very dangerous. However, by this time she has already suffered terribly at the hands of Ikejima who also got her hooked on drugs.

Takashi Ishii really puts this version of Nami through the wringer as she descends into a drug-fuelled downward spiral of degradation in backstreet brothels until Muraki manages to find her again and help her shake her addiction and to regain her vengeful focus. One gets the feeling we are heading to a bloody and bleak finale, which is true to some extent; however, the final confrontation is wonderfully staged on a warehouse roof, drenched in neon fluorescence and copious blood. It reaches a satisfying crescendo and a twist that works if one only guesses shortly before the reveal.

Although not for everyone—viewer discretion is recommended–this box set is one emotional rollercoaster and quite a journey.

JAPAN | 1994 | 108 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

director: Takashi Ishii.

writers: Takashi Ishii • Bo Nishimura (Original).

starring: Kimiko Yo, Maiko Kawakami, Yui Natsukawa, Shinobu Ôtake, Jinpachi Nezu, Naoto Takenaka & Kippei Shîna.