STOWAWAY (2021)

A three-person crew on a mission to Mars faces an impossible choice when an unplanned passenger jeopardizes the lives of everyone on board.

A three-person crew on a mission to Mars faces an impossible choice when an unplanned passenger jeopardizes the lives of everyone on board.

At the heart of Joe Penna’s second feature lies a simple, age-old moral problem: is it ever right to kill somebody in order to save others? Stowaway frames the question openly and fairly unemotionally, with one of its four-strong cast coming firmly down on the utilitarian side that says ‘yes’, another unable to stomach anything but ‘no’, a third agonising between the choices… and the fourth person firmly committed to ‘no’ because he’s the one liable to be sacrificed for the greater good.

It maintains interest by acknowledging both arguments and not allowing the conclusion to seem foregone; though its resolution is firmly humanist, there’s never any demonisation of those who reluctantly decide that Michael (Shamier Adams), an unplanned fourth passenger on a spacecraft designed to keep only three alive, must be removed from the equation with a fatal injection.

The time is, apparently, the relatively near future. Experienced astronaut Marina (Toni Collette) and two novices—medical scientist Zoe (Anna Kendrick) and biologist David (Daniel Dae Kim)—leave Earth on a two-year round trip to a small colony on Mars. Not long after their departure, Marina’s shocked to discover Michael concealed behind a panel in the craft. “Who the fuck is on my ship?” she demands to know. The answer is that he, an engineer working at the launch site, was knocked unconscious sometime before liftoff and inadvertently began the journey into space with the crew.

It’s too late to turn back, and what’s worse is that Michael’s unconscious body has also damaged the craft’s carbon dioxide scrubber, which is essential in keeping the air breathable. There’s no backup scrubber (it’s hinted that the commercial organisation operating these Mars missions is trying to cut costs), and before long the crew are facing a terrible but inevitable truth: they won’t have enough oxygen to support four people for the duration of their voyage, so someone has to go, because if not… everyone will die. The moral calculus is then further complicated by the fact that, although Michael’s the least able to contribute to the running of the spacecraft, he’s also the only one who didn’t volunteer for a dangerous expedition.

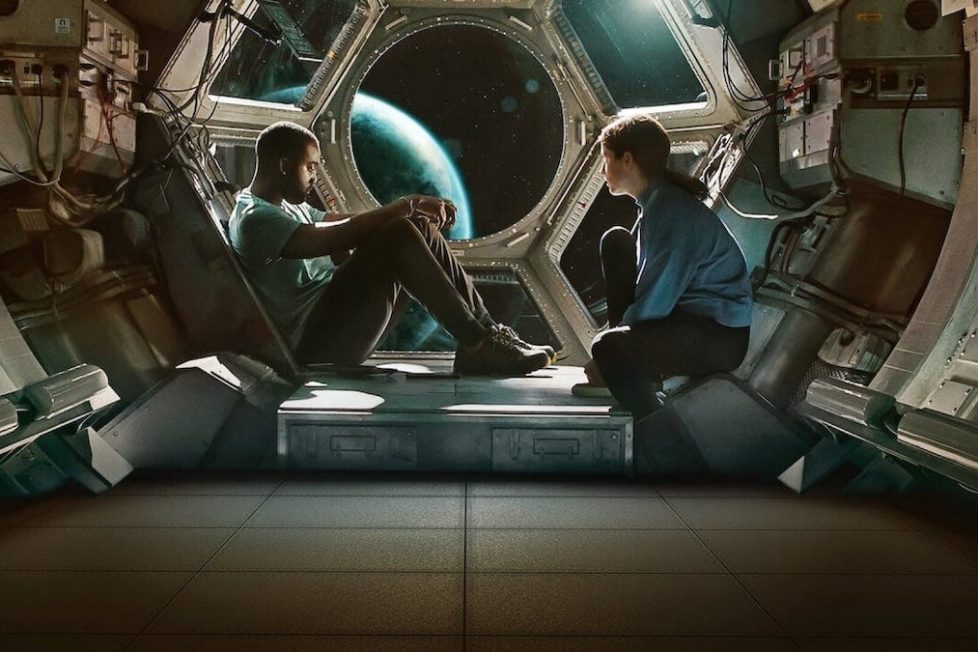

The entire film takes place in and around the craft, which looks pleasingly plausible. Of course, it’s more spacious than it probably would be in reality, to permit multiple camera angles and not constrain the actors excessively, but it’s crammed with equipment and seems to be the work of engineers rather than interior designers. Indeed, apart from a painstakingly depicted an undramatic spacewalk toward the end, space itself doesn’t get much of a look-in. Stowaway could, with some tweaks to the premise, just as easily be set in a submarine or in any hostile environment with limited resources.

Space works especially well as a setting because the prospects of rescue are so obviously zero, but viewers hoping for a traditional “astronaut movie” may be disappointed. Even the launch, usually a scene of great intensity, is far tamer than the same sequence in the likes of Apollo 13 (1995) or First Man (2018). There are few of the conventional drama-generating crises to distract from the dilemma of Michael and the dwindling oxygen, and Penna and co-writer Ryan Morrison appear to be having a little fun with their own narrative restraints when the camera eventually does leave the spacecraft for the final act, introducing a Chekhov’s Gun that fails to fire. (The commander emphatically warns two astronauts that on no account must they damage a certain component, and… they don’t.)

As a result Stowaway can feel, if not exactly slow, certainly lacking in incident. It’s a movie that gradually inches ahead, as one possible course of action after another is rejected by the characters or turns out to be a dead end, and it’s also a film of great clarity with no mysteries. But the largely unchanging situation is effective in itself, because the longer the oxygen problem stays unresolved the bigger the threat grows, and by the conclusion a real sense of urgency has been amassed.

Character conflict is similarly low-key. One keeps expecting dark motives or hidden aggression to surface, but they never do. None of the four characters ever really fall out with any of the others, as Stowaway’s more about the conflict of human values with logical necessity. This means there’s little scope for big emotive scenes, and while Penna and Morrison do try to sketch in some backstories, it’s left to the actors to make them credible. In this they succeed, and even if we don’t ever feel we completely understand the characters, we certainly believe in them.

Adams, as “stowaway” Michael, is the stand-out, perhaps because he has the subtlest part. He’s intelligent yet a little naive, scared yet not falling to pieces. His relationship to the craft and to Earth is different from everyone else’s, and his panic when he first sees our planet through a window—and realises where he is—makes for a striking scene. Collette gives a fine performance as the commander, too, who isn’t weak but feeling the burden while trying to be decisive and sympathetic at the same time.

Kendrick takes a while to convince, but only because she looks too young for the part (despite being nearly 35). She handles some of the most important scenes with the right level of emotion. Kim’s David is calmer and (along with Collette’s commander) the character we know the least about—but this also makes him interestingly watchable, because we can’t be sure what his opinion is. By contrast, stowaway Michael and Kendrick’s doctor Zoe, although their feelings are much more exposed, are just a little too faultless.

Penna and cinematographer Klemens Becker shoot matter-of-factly without letting style get in the way of narrative, but there’s some effective composition and the spacewalk is especially well presented and powerfully conveys a vast emptiness. This sequence soon leads to the final one, also outside the spacecraft, where they at last succumb to the allure of aesthetics and deliver a gorgeously photographed, hauntingly lit stillness after all the agonising. The score by Hauschka (Volker Bertelmann) is similarly understated, completing rather than creating the mood of scenes, but taking on extra importance in the many passages (such as the spacewalk) which have little or no dialogue or ambient sound.

Stowaway has much in common with Penna’s previous film written with Morrison, Arctic (2018), where Mads Mikkelsen (much like Stowaway’s characters) has to answer hard questions of survival in a stripped-back, resource-sparse setting. The fascinated attention it pays to technical detail also recalls Ridley Scott’s The Martian (2015), and the combination makes for a movie that engrosses us in a tough question and feels very real.

Perhaps the central idea of the accidental “stowaway” isn’t all that believable, perhaps the characters are frustratingly inaccessible at times, and perhaps the final resolution is a bit predictable (though given the very limited number of possible resolutions, how could it not be?) But none of this detracts from the power of the situation that Stowaway sets up, or the patient and undeviating way it follows through to a tragic and inexorable conclusion.

USA • GERMANY | 2021 | 116 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Joe Penna.

writers: Joe Penna & Ryan Morrison.

starring: Anna Kendrick, Daniel Dae Kim, Shamier Anderson & Toni Collette.