THE ROARING TWENTIES (1939)

Three men attempt to make a living in Prohibitionist America after returning home from fighting together in World War I.

Three men attempt to make a living in Prohibitionist America after returning home from fighting together in World War I.

While often relegated to a footnote in histories of major gangster films, the influence of Raoul Walsh’s The Roaring Twenties reverberates through key films that would resurrect the genre some 30 years later. Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972) contains knowing references to several scenes, and Sergio Leone’s magnum opus Once Upon a Time in America (1982) exhibits clear structural and thematic parallels. Therefore, this impressive new 4K digital restoration from the Criterion Collection presents a long-overdue opportunity to re-evaluate a classic starring two Hollywood heavyweights—James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart.

The narrative is presented as a semi-documentary, punctuated throughout with newsreel-style montages marking the passage of time from year to year. These inserts inevitably interrupt the flow of the story, but they keep up the pace by connecting key events and jumping over the boring bits.

During the opening sequence, much is made of the factual basis of the story, emphasising that although fictionalised, it’s inspired by historical events. After establishing World War I as its backdrop, the first face we see is that of Eddie Bartlett (James Cagney) as he looks up from the mud after being knocked flat by a nearby explosion. Realising he’s in the midst of heavy shelling, he throws himself into the nearest shell-hole, literally landing on top of George Hally (Humphrey Bogart).

Right from the start, the dialogue is quick and witty, with Hally admonishing Bartlett for his abrupt entrance, who retorts with, “What’d you expect me to do? Knock?” He breaks out a fresh packet of cigarettes to smooth things over, but they’re interrupted by a third young soldier, Lloyd Hart (Jeffrey Lynn), tumbling in to join them. In these first few moments, we’re introduced to three characters who meet in extremis and could have died that same day, but whose destinies are now entwined.

At base camp, Bartlett opens a letter from Jean, a young woman he’s never met—just one of many who volunteered to write to servicemen on the front line to boost their morale. This time, she’s enclosed a sultry photograph and Bartlett seems smitten. In the background, George is having an altercation with their sergeant (Joe Sawyer). This reveals that they know each other back home, and that George considers himself of higher social standing in civilian life, introducing a recurring theme of class division and economic disparity.

Back on the battlefield, Eddie, George, and Lloyd find themselves entrenched in the ruins of a bombed-out building, picking off the enemy as they advance out of sight. Their characters are efficiently established through some terse dialogue.

We learn that after the war, Eddie wants to pick up where he left off as a car mechanic. Lloyd, a recent law school graduate, is intent on setting up his own practice and demonstrates his moral core when he aims at a target, then lowers his rifle without firing. When George questions his actions, Lloyd explains that the soldier he had in his sights looked no more than 15. In response, George takes a shot, remarking, “Well, he won’t be 16…”

Just seconds later, a dispatch arrives announcing the armistice (ceasefire), news met with relief by Eddie and Lloyd. George, however, shows no remorse or regret, simply saying of his gun, “I like this, think I’ll keep it.”

From the start, then, we have clearly delineated archetypal characters: the down-to-earth working-class Eddie; the upstanding, principled Lloyd; and the cold, amoral George. How will each fare in the changing times to come?

With the outbreak of World War II during filming, what were once thought of as the ‘post-war years’ had become the ‘interwar era’. However, the US wouldn’t be directly involved for another couple of years. Therefore, The Roaring Twenties can be read as a very clear cautionary tale, critical of an America where men returned from defending democracy—as the opening narration puts it—only to find the economy floundering and their freedoms about to be curtailed by Prohibition.

Prohibition was ostensibly enforced to prevent moral corruption and deter down-on-their-luck ex-servicemen and the ranks of the unemployed from drowning their sorrows and drinking themselves to an early grave. However, it was an early example of a populist government pandering to Christian fundamentalists with an eye on manipulating the situation for power and personal gain. Many right-wing politicians used the issue as their soapbox, while taking bribes from the very gangs they denounced. These gangs also rose to power on the plentiful profits made from racketeering and bootlegging. Gradually, US politics fell under the influence of the gangs that the legislation inadvertently supported.

Back in New York’s Lower East Side, Eddie convinces his flatmate and cabbie, Danny (Frank McHugh), to drive him over to meet his pen-pal. He’s surprised to find that she’s not the enchantress her photo implied, but a teenager fresh out of high school. This Jean (Priscilla Lane) isn’t what he was hoping for.

He also finds his rent’s gone up and there’s no longer a job for him at the garage where he used to work. So, he takes up Danny’s offer to share his cab and run a night-and-day service between them.

Eddie is certainly trying to earn an honest living. However, when he’s asked to deliver a package to a nightclub, he innocently agrees, perhaps thinking that a taxi service has the potential to expand into a delivery service. As he hands the item to the hostess of the Panama Club, ‘Panama Smith’ (Gladys George), two plain-clothes federal agents jump him, revealing it to be a flagon of illicit liquor. The 18th Amendment of 1919, which called for curbing sales of strong liquor, had just been bolstered by the Volstead Act, making the sale of any alcoholic beverage illegal. This presented plenty of opportunity for criminals to supply a long-standing, suddenly unmet demand.

As an aside, it’s interesting to think that on a night in 1920, one might be smoking a spliff and having a tot of whisky—both legal pastimes… until the stroke of midnight when, suddenly, mid-sip you are transformed into a criminal as alcohol becomes a banned substance. It wouldn’t be until the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937—four years after Prohibition was repealed—that the reverse would happen.

Without implicating Panama, Eddie is found guilty and ordered to pay a fine or serve time. Here, that theme of economic disparity resurfaces. The new laws don’t affect the wealthy as much because they can afford the fines, but Eddie has no such choice. After a short spell in jail, Panama posts bail for Eddie, and a friendship is kindled.

With his new contacts in the shady world of nightclubs, Eddie sees a business opportunity to do exactly what he was wrongly accused of: using his and Danny’s taxi service as a front for delivering alcohol to the burgeoning speakeasy scene. He calls upon his army pal, Lloyd Hart, to provide legal services. But it’s not long before they realise they don’t have to remain ‘middlemen’ and can make their own ‘bathtub gin’. The profits pay for more cabs, and their distribution network steadily grows until they’re brewing bootleg liquor on an industrial scale.

Whilst visiting a club to chase an overdue payment, Eddie stumbles upon a rehearsal and recognises Jean in the chorus line. Over the years since he last saw her, she’s blossomed into a beautiful young woman, closer to the image he formed from reading her letters on the frontline. They begin seeing each other socially, and he arranges an audition at the Panama Club for the headline act.

A classic love triangle unfolds. Eddie harbours unrequited feelings for Jean, while remaining oblivious to the affections Panama clearly has for him. It isn’t long before the triangle morphs into a rectangle as Jean falls for the taller, more handsome, and more honest Lloyd.

The narrative takes a dramatic turn. The crime thriller with neo-noir undertones now fuses with melodrama, and things take a darker turn when the ruthless and unreliable George reappears by chance. He proposes a partnership with Eddie while covertly manipulating him against Nick Brown (Paul Kelly), the murderous boss of a rival Italian mob.

The film began life as a 1938 short story titled The World Has Moved On, written by veteran Broadway columnist Mark Hellinger. Hellinger even endorsed the finished film with a to-camera monologue for the theatrical trailer. His original title was discarded because it was too close to John Ford’s earlier film The World Moves On (1934), which it was intentionally referencing. However, the rather workmanlike script had undergone the usual redrafting by a team of writers at Warner Bros. Regular collaborators Jerry Wald, Richard Macaulay, and Robert Rossen finalised it.

Reputedly, director Raoul Walsh found the result to lack pep and pace. He often called upon Cagney, McHugh, and Bogart to write their own improvised dialogue, bouncing off each other to keep things lively. McHugh and Cagney were already best friends and often worked together. Bogart and Cagney, having both started out on the New York stage in the 1920s, already had some rapport, and they were fresh from working together in Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), which won Cagney a couple of ‘Best Actor’ awards and his first Academy Award nomination for his bravura portrayal of Rocky Sullivan.

Cleverly adhering to the restrictions of the Hays Code, the remorseful tough guy goes to the electric chair feigning cowardice to deter his young and impressionable admirers from following a similar life of crime. It’s possibly the most powerful and heart-rending finales the gangster genre has ever produced, although The Roaring Twenties also delivers on that front.

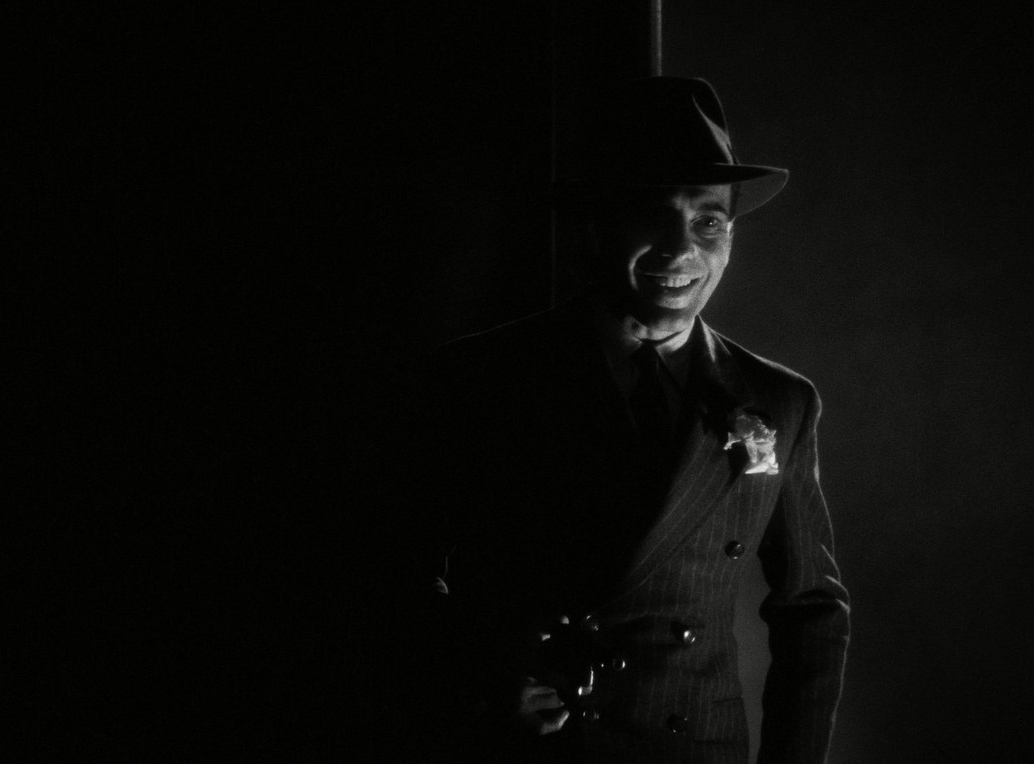

The resulting rapid-fire, often witty dialogue is one of The Roaring Twenties’ several strengths. This is alongside an exceptional ensemble cast and sympathetic cinematography in the capable hands of Ernest Haller, who was just about to embark on Gone With the Wind (1939). Haller certainly knows how to utilise pin spots to add sparkle to a performance, making an actor’s eyes shine. Here, he employs this technique on James Cagney in a few of the more emotional scenes, but generally reserves it to emphasise the ‘doe-eyed’ beauty of Priscilla Lane.

Lane, just a couple of years into her acting career, delivers a competent performance. However, her background as a singer comes to the fore when she performs the old pre-war standard, “My Melancholy Baby,” written in 1912. This is alongside a couple of more jaunty numbers that are contemporary with the film’s 1920s setting: “It Had to be You” and “I’m Just Wild About Harry.” At the time, these musical interludes would have been nostalgic crowd-pleasers, but they can be tiresome for a modern audience. They slow things down but also give us a chance to observe the one-sided dynamic between Eddie and Panama as she watches him watch Jean.

Lane went on to have a relatively slow but steady career, with some 20 appearances spread over 20 years. Notably, she starred in Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942) and is perhaps best known for her role as Elaine, the fiancée of Mortimer Brewster (Cary Grant) in Arsenic and Old Lace (1944).

Gladys George imbues Panama with a real human presence. This is conveyed through subtle micro-expressions that somehow manage to elevate her performance beyond a potential cliché. Apparently, Hellinger had loosely based her character on the famous entertainer, silent film actress, entrepreneur, con-woman, and speakeasy hostess, Texas Guinan. Guinan, for a time, was in partnership with Larry Fay, one of the earliest bootleggers to operate in New York while running a taxicab business as a cover. He was the inspiration for Eddie Bartlett’s character.

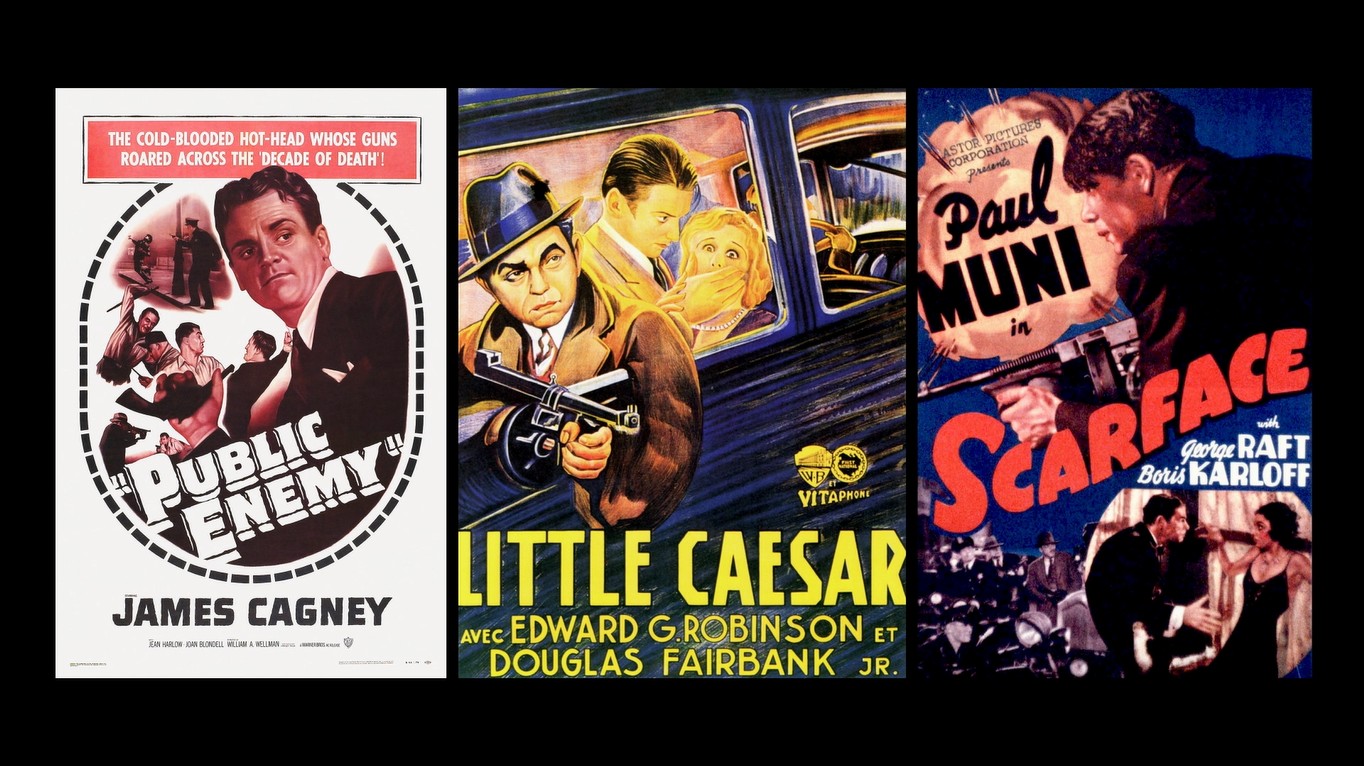

James Cagney shot to stardom as a tough guy in his leading role as Tom Powers in The Public Enemy (1931). This film, along with Mervyn LeRoy’s Little Caesar (1931) and Howard Hawks’ Scarface (1932), is credited with birthing the gangster genre. But Cagney’s talents extended far beyond gangsters. He proved himself a versatile actor, excelling in Shakespearean plays, comedies, and musicals.

Here, he delivers a superb performance in a role that seems tailor-made for him. His screen presence is so dominating that it’s hard to focus on anyone else when he shares a scene. He portrays a complex character—a well-meaning man with deep flaws who makes poor choices. However, he lacks the ruthlessness necessary to truly succeed as a gangster.

Cagney would reunite with director Raoul Walsh on several occasions. They collaborated on the romantic comedy The Strawberry Blonde (1941) with Rita Hayworth, the unforgettable gangster flick White Heat (1949) where Cagney plays the unhinged Cody Jarrett, and the political thriller A Lion is in the Streets (1953).

Humphrey Bogart is fine too, but there’s not so much depth to plumb with George as he’s obviously a nasty piece of work from the outset—a self-obsessed, sociopathic villain with a stunted emotional range. Bogart was on the cusp of stardom, and this would be one of the last times he’d play such a supporting role. He worked with Raoul Walsh again on the excellent noir thriller, They Drive by Night (1940), and Walsh’s heist film High Sierra (1940). The following year, he’d star as Sam Spade, alongside Gladys George again, in John Huston’s classic noir The Maltese Falcon (1941), a performance that propelled him onto the Hollywood A-list until his final film, The Harder They Fall (1956).

Of course, The Roaring Twenties has dated, but at the same time it’s aged well, as it was made with a strong dose of nostalgia from the outset. The story is told from a time of impending war, looking back on a previous war and then covering the crime-ridden Prohibition era—which was also the swinging Jazz Age—that presaged the 1929 Wall Street Crash and the Great Depression, which America was just beginning to recover from when the film was released.

At the time, it was a box office hit, but the popularity of the gangster genre was waning, partly due to the Hays Code which made such subjects difficult to portray. Raoul Walsh partly compensated for this hindrance by downplaying the criminal themes and foregrounding the interpersonal drama of friendship and romance, loyalty and betrayal.

The poetically tragic ending remains a classic of the genre, and I won’t give too much away by saying that it cleverly adheres to the Hays Code while allowing an honourable act of violence and self-sacrifice for the good of others with no personal gain except redemption.

USA | 1939 | 107 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Raoul Walsh.

writers: Jerry Wald, Richard Macaulay & Robert Rossen (based on the 1938 short story ‘The World Moves On’ by Mark Hellinger).

starring: James Cagney, Priscilla Lane, Humphrey Bogart, Gladys George, Jeffrey Lynn, Frank McHugh, George Meeker, Paul Kelly, Elisabeth Risdon, Edward Keane, Joseph Sawyer & Abner Biberman.