RANGO (2011)

An ordinary chameleon accidentally winds up in the town of Dirt, a lawless outpost in the Wild West in desperate need of a new sheriff.

An ordinary chameleon accidentally winds up in the town of Dirt, a lawless outpost in the Wild West in desperate need of a new sheriff.

There are animated films that entertain through spectacle, and there are animated films that use spectacle to think. Rango is emphatically the latter: a spaghetti western rendered in CG that refuses the safety of “cute”, the comfort of polish, and the easy win of pop-culture winks. It’s a studio film with an uncommercial face, and 15 years on, that’s precisely why it feels more vital than most of its contemporaries.

You don’t need to catch every reference to enjoy it: it plays first as a funny, tense, dusty western—and only then as a clever one.

When Gore Verbinski was offered the project—fresh off his Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy—he could’ve delivered a perfectly serviceable family adventure. Instead, he made something stranger: an animated film staged like live-action cinema, designed with the harsh tactility of a proper western, and willing to let silence, unease, and asymmetrical faces do the work that other films outsource to rapid-fire gags.

The production itself was unconventional. Verbinski gathered his voice cast (Johnny Depp, Isla Fisher, Bill Nighy, Alfred Molina, etc) and recorded them not in isolated booths, but together on a makeshift soundstage, in costume, improvising like a theatre troupe. This wasn’t a gimmick; it was a philosophy. He wanted performances, not vocal “turns”: actors reacting in real time, occupying space, and letting pauses breathe. That decision reverberates through the film’s rhythm. Rango doesn’t sprint; it drawls. Characters interrupt each other, talk over each other, and leave things unfinished. It feels less like animation voice work and more like a dusty repertory company finding its timing on stage.

ILM—handling animation for the first time as a standalone feature—matched that ethos with a visual language that prioritised texture over sheen. It’s worth noting that this “rougher” aesthetic isn’t only an artistic provocation; it’s also a pragmatic one. A world built from grit, fibre, and hard light can be cheaper—and smarter—than a world that has to be constantly “perfect”. Less gloss means fewer surfaces that immediately date. The film’s restraint becomes an advantage: what might read as austerity in the moment becomes longevity over time.

Dirt—the desperate desert town where our chameleon lands—looks like a place you could scrape off your boots. Cracked wood, blown sand, sun-bleached signage, dehydrated skin. Even the air looks dry. It’s a world built from splinters, and that tactile commitment gives the comedy a floor to stand on. Jokes land harder when the world has weight. And it is, crucially, genuinely funny: dry, weird, and sharply timed.

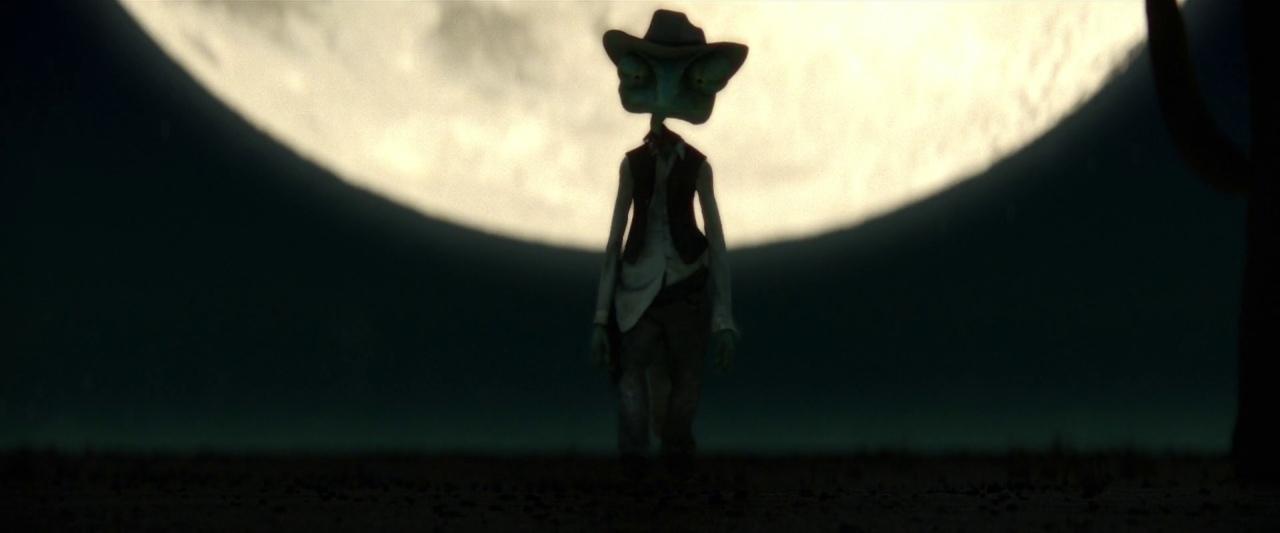

The character design refuses the safety net of marketability. Faces are sharp, asymmetrical, and weathered. Bodies are specialised, sometimes frankly grotesque. It’s a gallery of creatures built from hard angles and lived-in detail, and that “anti-cute” choice is exactly why the film is so memorable. These aren’t characters engineered for plush toys; they’re silhouettes you recognise instantly, with expressions that don’t rely on rubbery exaggeration. The eyes alone do enormous work—not just for comedy, but for suspicion, unease, and that specific western sensation of being watched and judged.

That abrasive palette is what allows the film to earn its moments of genuine sweetness without tipping into syrup. Priscilla, the small, tough young mouse navigating Dirt with bruised pragmatism, might be one of the most quietly lovable characters in modern animation precisely because she isn’t written as a product. She’s decent and brave in small ways—emotionally legible without being sentimental. The contrast is what makes her land: placed inside a world of cranks, conmen, and predators, her softness registers as real rather than manufactured.

Verbinski’s direction treats animated scenes like live-action scenes. The blocking is deliberate; characters occupy frames the way actors do. Crowd scenes have legibility. Geography matters. Dirt isn’t a blurry, convenient background; it’s a town with social architecture. Who stands on the porch, who is stuck below, who huddles together, and who keeps their distance—those are visual choices that build status and pressure without needing dialogue to explain it. This is where the Leone and Ford DNA comes in, not as imitation but as instinct: tension, pauses, and the theatrical dead air before a line lands. Timing as a weapon.

And because the film treats its desert like a physical ecosystem rather than a cartoon backdrop, it earns moments of genuine menace. There’s a particular kind of western dread in how danger appears here: not always announced, sometimes simply emerging—as if the land itself has compartments. Predators don’t arrive like a punchline; they surface like the world’s logic asserting itself. Dirt is not a safe stage for jokes. It’s a place where the ground can feel complicit.

Johnny Depp’s voice performance fits the film’s obsession with performance perfectly. He plays Rango as a creature made of theatre—a desperate little actor who can’t stop narrating himself, rehearsing himself, and auditioning for meaning. The comedy isn’t just in the lines; it’s in the rhythm, the insecurity, and the way bravado keeps slipping into panic. The supporting voices are equally well-judged: Bill Nighy brings menace without cartoony theatrics; the film treats danger with a dry authority, never tipping into “kiddie panto”.

What’s striking is how Rango handles its “big ideas” without turning into a lecture. The film has politics—the kind that naturally emerge in a desert town where survival depends on resources—but it doesn’t announce them with capital letters. Scarcity becomes power. Power becomes story. There’s a light echo of Chinatown (1974) here, not in plot mechanics but in vibe: the sense that control of something basic and almost invisible can organise an entire community’s reality. Rango smuggles that undercurrent into a family-friendly package, then keeps moving. It doesn’t stop to congratulate itself.

When Rango arrived in March 2011, it felt out of step with the animation landscape: too strange, too dusty, too aesthetically unmarketable. It was a financial success—$245M worldwide against a $135M budget—and it won the Academy Award for ‘Best Animated Feature’, then did something even rarer: it stopped. No franchise dilution. No “universe”. No aesthetic flattened into a template.

That refusal to be replicated is part of why the film’s legacy is so strong. Its influence has been quieter: you can see echoes of its tactile ethos in later films that try to give CG worlds weight and lived-in grime—but few go as far as Rango does in refusing prettiness. The ugliness isn’t a stunt; it’s character. The dryness isn’t a filter; it’s atmosphere.

If anything, Rango plays better now than it did on release. Contemporary animation has become increasingly polished, increasingly interchangeable—frictionless surfaces, friendly faces, and palettes optimised for universal comfort. Rango goes the other way. It embraces the western’s harshness—not as cruelty, but as a way of making comedy sharper and stakes more tangible. The jokes don’t float; they scrape, they clack, and they creak like wood in the sun.

None of this requires you to “decode” the film. You don’t need a thesis to enjoy it. That’s the point: Rango is simply a movie with unusually strong craft—design that doesn’t age because it wasn’t chasing a trend; direction that understands space and timing; humour that doesn’t panic; and a world coherent enough to carry both silliness and threat in the same frame. It feels carved rather than rendered.

That’s the best reason to revisit it. Rango isn’t a museum piece, and it isn’t a smug “look how clever we are” artefact. It’s a rare kind of animated feature: one that respects the western as a form, respects the audience as capable, and respects the physicality of its own world. If you missed it the first time, it’s one of the easiest recommendations in modern studio animation: weird, funny, and still beautifully made.

USA • UK | 2011 | 107 MINUTES • 112 MINUTES (EXTENDED) | 2.35:1 • 1.78:1 (HDTV) | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Gore Verbinski.

writer: John Logan (story by John Logan, Gore Verbinski & James Ward Byrkit).

voices: Johnny Depp, Isla Fisher, Abigail Breslin, Bill Nighy, Alfred Molina, Timothy Olyphant, Harry Dean Stanton & Ray Winstone.