ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA (1984)

A former Prohibition-era Jewish gangster returns to the Lower East Side of Manhattan 35 years later, where he must once again confront the ghosts and regrets of his old life.

A former Prohibition-era Jewish gangster returns to the Lower East Side of Manhattan 35 years later, where he must once again confront the ghosts and regrets of his old life.

When I’m asked what my favourite films are, there are usually three answers I give: 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), a spectacle of probing science fiction with a touch of ominous mystery. The Thin Red Line (1998), which combines terrifying sequences from the Guadalcanal Campaign in World War II with existentialist themes in an avant-garde style. And the third film I always recommend is Once Upon a Time in America.

There are simply very few films superior to Sergio Leone’s masterpiece. It encapsulates everything that makes cinema such a captivating medium, both in its visual splendour and in its unique capacity for storytelling. The film boasts rich, multifaceted characters. The editing evokes the workings of the subconscious mind, while the cinematography allows us to traverse time seamlessly. And Ennio Morricone’s score is amongst the most beautiful I’ve ever encountered.

The story chronicles the lives of five friends throughout their pursuit of fortune and notoriety in Prohibition-era New York.

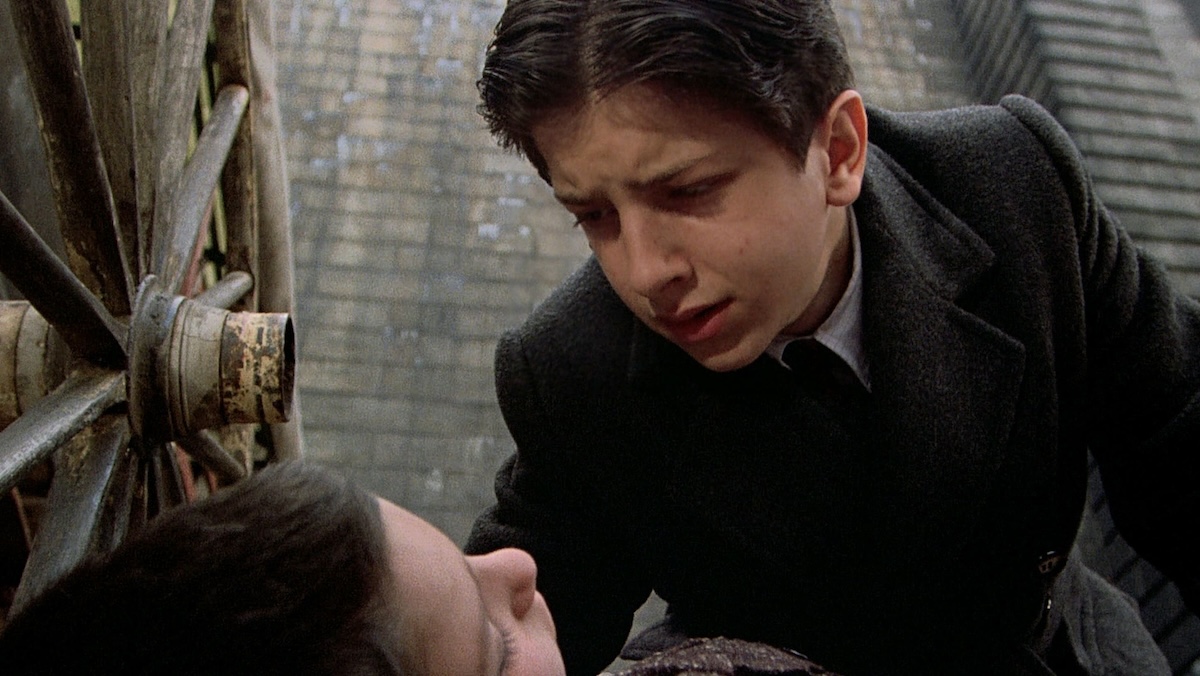

Our tale opens in 1923, with David Aaronson (Scott Tiler)—known by the nickname “Noodles”—trying to make his mark on the crime-ridden streets of Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Along with his friends Maximilian “Max” Bercovicz (Rusty Jacobs), Philip “Cockeye” Stein (Adrian Curran), Patrick “Patsy” Goldberg (Brian Bloom), and Dominic (Noah Moazezi), the gang chases the American Dream.

As they soon discover, life is full of unforeseen pitfalls. When Noodles (now played by Robert De Niro) is released from prison in 1931, their destinies have already been forged. They are now grown men, determined to become the top bootleggers in the business. Max (James Woods) is running the show, while Patsy (James Hayden) and Cockeye (William Forsythe) serve as loyal members of their quartet. But it soon becomes clear that these childhood friends cannot remain so forever.

35 years after escaping New York amid a catastrophic event, Noodles returns from his self-imposed exile. He’s keen to discover who stole the million dollars the gang had stashed away, and who sent him an ominous letter, bidding him to return.

When questioned about the message, he replies: “It means: ‘Noodles, though you’ve been hiding in the asshole of the world, we found you. We know where you are.’ It means, ‘Get ready.’”

There’s something utterly ethereal about this classic 1984 film. Sergio Leone conjures a magical, tragically poignant atmosphere, turning the work into an epic exploration of dreams, memory, regret, time, poverty, desperation, power, and the American Dream. It’s also a fascinating example of a coming-of-age story where the protagonists never mature: all of them are, in some way, trapped by the past. The result is a wholly unique film, unlike anything I’ve seen since I first watched it as a teenager.

How does one begin an epic of such magnitude? A film conceived as a six-hour experience needs a momentous starting point, and Leone delivers precisely that. This four-hour odyssey commences at the very moment Noodles’ life unravels. We are plunged into a scene of violence, witnessing the brutalisation and murder of his friends and lovers. The reasons for this shocking display remain tantalisingly unclear.

It’s a gripping start to a patient film. Leone wisely begins in medias res; understanding that there’s a long story ahead, the Italian filmmaker throws the audience into the middle of the action, with some pre-existing conflict to keep us hooked. In this respect, it’s practically Shakespearean. However, due to Leone’s non-linear narrative, he has essentially placed us at the climax (the end of Act 4 in a Shakespearean play is typically associated with the protagonist’s downfall). This is telling, to say the least.

By doing this, Leone already gives us a great deal of insight into the story’s themes. Most importantly, we’re shown the consequences of one man’s chase for the American Dream. While Noodles and Max might have begun with good intentions—to escape poverty, become wealthy, and achieve everything they ever desired—they become utterly ruthless in trying to obtain that which exceeds their grasp.

Leone seemingly offers a very subtle critique of the society that has instilled these boys with such dreams, a society that simultaneously denies them the legitimate means to achieve their goals. Even as pre-teens, they’re aware that the path to rapid advancement lies in becoming the most cunning criminal on the streets: setting fire to a newspaper stand, rolling a drunk, or striking a shady deal with the police. All their exploits become a mere means to an end.

Since the boys seemingly lack any parental figure in their lives, they hurtle down this path unhindered. As a result, their borderline psychopathic behaviour becomes the norm for them. This is precisely what has allowed them to emerge from their adolescence as anything more than petty criminals. Leone seems to suggest that, in the pursuit of the American Dream, a moral compass becomes nothing more than a hindrance. The rewards of criminality incentivise ruthlessness; they all benefit from their violent behaviour.

This makes our protagonists a collection of complicated characters. Desperate to grow up, become men, and carve out a niche for themselves in life, they remain oblivious to the pain and suffering they cause. As a result, there’s nothing they wouldn’t do. Does this make them bad people? Well, yes. Yet, we still find ourselves empathising with them.

I have questioned why we still identify with these characters even after watching them commit heinous crimes. Is this just the power of masterful filmmaking, capable of making us understand even when we don’t condone or forgive? Leone invites you to see their humanity, even after showing you the darkest depths of their dysfunction. It seems to me that, as Leone romanticises his characters, we can’t help but romanticise them as well.

Perhaps it’s how our characters embody the rapid growth of America, a young nation that soon found itself wielding immense power. As Max observes: “This country’s still growing up. Some diseases you’re better off having when you’re still young.” What disease is Leone referring to? The rampant corruption that’s ingrained in achieving the American Dream, the merciless violence and burning greed that lurks beneath the very thin veneer of success.

Leone’s film chronicles the emergence of a new world, a frightening, unformed place. Tellingly, those who are shaping it do so without a conscience. Our protagonists are like virulent weeds, a virus that binds to its host before it can defend itself. Even the title of the film suggests this. It implies that a dark acquisitiveness has been present from the very foundation of the nation, pervading it ever since.

This is a theme present in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972) and Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990). Once Upon a Time in America finds itself set apart from these two classics in several ways, however. Firstly, Leone’s film is far more melancholic than either of the aforementioned gangster flicks. While Henry Hill concludes with a monologue brimming with disdain for the ordinary life he leads—a stark contrast to his days as a flamboyant gangster celebrity—Noodles is consumed by a deep sense of regret. Perhaps for the wrong reasons (he appears less concerned about those he has harmed than the impact it’s had on his own life), but regretful he remains nonetheless.

Secondly, Leone’s film offers a more nuanced perspective on masculinity than is present in The Godfather or Goodfellas. Both Noodles and, especially, Max, demonstrate a disturbing inability to regulate their emotions. This was perhaps unsurprising in 1920s America. However, it remains interesting how their emotional fragility is often linked to a desire to evince their inviolable masculinity, in all its heartless, callous glory. In this way, Leone inextricably links their insecurities with wanton acts of cruelty, all fuelled by a woeful lack of emotional intelligence.

Having said all this, it would be a mistake to characterise our protagonists as unfeeling monsters. They perhaps come across more as being out of their depth, like children trying to stay ahead of the game. Entering the rat race at such a young age, their sole ambition was simply to get a good start. As Noodles melancholically reflects: “You can always tell the winners at the starting gate. You can always tell the winners, and you can tell the losers.”

When his old friend, Fat Moe (Larry Rapp), cheerfully assures him, I’d have put everything I ever had on you,” Noodles replies solemnly, “Yeah… And you would’ve lost.” He knows now, all too late, that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Now, he wonders if their intentions were ever good in the first place.

Leone’s masterpiece prominently features themes of the past, our memories of it, and the regret it evokes. Noodles involuntarily remembers a significant moment in his life whenever he sees or hears something. This imbues the film with a Proustian quality. It often feels as though Noodles is not truly searching for the truth behind the letter he receives, but rather for a vague, undefined moment of past happiness. Did such a time even exist? He cannot be certain. As Deborah (Elizabeth McGovern) mournfully states: “All that we have left now are our memories.” Unfortunately, even memories can’t be trusted.

Indeed, Leone’s drama is less a crime flick than an exploration of the human condition. Unlike other crime films, gangster action is largely eschewed in favour of a more introspective tone. The film often feels like a collection of vignettes: the formative events that turned these boys into the dysfunctional men they become.

Some of these moments are charmingly sweet. As a pre-teen, Patsy sits on the stairs waiting for Peggy (Julie Cohen), a young prostitute who will offer her services in exchange for a cupcake topped with a strawberry, nestled in a sea of whipped cream.

However, the anxious boy’s nascent manhood isn’t yet strong enough to restrain his childish impulses. Seized by the allure of the sweet treat, he devours it on the stairs before Peggy can even emerge from her room. These intimate glimpses into their youthful innocence, an innocence that will be stripped away by their violent actions, serve to humanise the characters.

My favourite scene in the whole film comes in one of these quiet moments. When Noodles is released from prison, he sees Deborah again for the first time in eight years. She’s the light in his life that’s kept him going, and it’s clear in De Niro’s eyes. Deborah tells him she dances every night, inviting him to watch her perform if he ever has the time. He smiles. “Every night,” he assures her.

As Leone allows these scenes to unfold at a steady, unhurried pace, we are utterly captivated by the film’s magic. Though it may be four hours long, it certainly doesn’t feel that way. This is because Leone imparts a genuine sense of having lived a life, of having experienced these moments with profound emotional intensity. Some of these moments will fade from memory, some may even have been figments of our imagination. But others will undoubtedly haunt us forever.

Leaning on themes of memory and regret, Leone skilfully weaves the concept of fate into the narrative. The number 35 appears ominously throughout the film. When Noodles and Max first meet, the stolen pocket watch reads 6:35. Noodles then disappears and lives a new life for 35 years. Intriguingly, both the first and final meetings between Noodles and Max are punctuated by a vehicle coming between them—the work of fate, perhaps? It certainly seems so. In their final encounter, a number—35—is scrawled on the side of the garbage truck that will ultimately obscure Max from Noodles’ view. The significance of this number remains a mystery.

Finally, idealisation emerges as a prominent theme in the story. This is most clearly seen in Noodles’ deification of Deborah, who becomes less of a person in his eyes and more like a celestial object; she is his donna angelicata, the Beatrice to his Dante. However, despite his impassioned declarations of love, Deborah sees straight through Noodles’ misguided and hopeless devotion. “You’d lock me up and throw away the key,” she accuses, a statement he cannot deny.

It also leads to the film’s most notorious scene: after Deborah informs Noodles that she’s leaving New York to pursue stardom in California, he rapes her in the back of their cab. The scene is so shocking that it has led many to dismiss the entire film as misogynistic schlock. This characterisation is one that McGovern strongly disagrees with. “It didn’t glamorise violent sex,” she said. “It is extremely uncomfortable to watch and it is meant to be…”

I imagine many viewers were so appalled by the scene because, up to this point, we’ve been rather complicit in the on-screen violence. I doubt many watched the gunfights with the same horror, at least. One explanation for this could be that we’re witnessing Noodles and his associates murdering corrupt police officers and gangsters. But then again, violence is violence. These are men who ruthlessly take what doesn’t belong to them. We’ve identified with them until we’re jolted into awareness. We feel a sense of betrayal for having empathised with dangerous men.

However, this dynamic also makes for a far more interesting film. After all, why should our protagonists be morally unambiguous? Few people in real life truly are. McGovern alludes to this point too: “If you say, ‘this violence is wrong’, you’d have to enlarge that to say, ‘all violence in movies is wrong’, and then you’d have to say, ‘you can only make movies about good people who obey the law and do right things, which (a) excludes a lot of what life is and (b) makes for some very boring movies.”

I concur with McGovern. Part of what makes Once Upon a Time in America such a riveting story is the complexity of the characters on screen. This isn’t to say that murder, rape, or child abduction are ethically vague—they are all abhorrent atrocities. However, by embedding us so deeply in the lives of our protagonists, Leone compels us to grapple with the characters we’ve come to know so well. In presenting us with the terrible potential humans possess, he denies us a bland viewing experience. This is just one of the many reasons behind the film’s artistic success.

Unfortunately, the film wasn’t a commercial success, although this wasn’t in any way due to its quality. In fact, it was a critical darling. After filming was completed, the footage ran for roughly 10 hours. Leone initially envisioned this being edited into two three-hour films. However, when the producers refused this idea, Leone adapted his vision to create a single, 229-minute film, which was met with great acclaim at Cannes.

Unfortunately, the film encountered further difficulties in reaching American audiences. The Ladd Company, the film’s US distributor, made significant cuts without director Sergio Leone’s approval or involvement. This reduced the running time to a mere two hours and 20 minutes. More concerning, they also restructured the film, abandoning its non-linear narrative for a more conventional chronological order. The result was an incomprehensible mess. This version was panned upon release and is credited with ruining the film’s reputation for years.

It was only years later, when audiences witnessed the awe-inspiring four-hour Director’s Cut on video, that Leone’s brilliance began to be truly appreciated. This belated adulation seems to contradict Ridley Scott’s recent claim that audiences have no appetite for films exceeding two and a half hours. Perhaps Scott has misjudged the situation. Audiences, it seems, weren’t averse to a four-hour epic—as long as it was Leone’s masterpiece. After all, when a film is as magnificent as Leone’s magnum opus, length becomes a secondary concern.

Considering his standing in popular culture, it’s surprising to think that Sergio Leone only directed seven films. The iconic Man with No Name trilogy (1964–66) and Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) alone account for four of his filmmaking ventures. His directorial debut, The Colossus of Rhodes (1961), a critical and commercial flop, has faded into the obscurity of history. Meanwhile, his criminally underrated Duck, You Sucker! (1971) is seldom mentioned.

Although he had a multitude of unrealised projects, Once Upon a Time in America was to be Leone’s final film. It feels rather fitting. Leone imbues the work with a meditative melancholy, creating a yearning for lost youth. While he intersperses moments of sadness with bursts of intense tension—Noodles tightening his grip on his suitcase while glancing over his shoulder never fails to make me hold my breath—the overall tone is mournful, introspective, and pensive.

Undeniably, the music of the great Ennio Morricone hugely enhances this film. While his score for The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) is likely his most recognisable work—it’s even been inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame—I would argue that this is his finest contribution to cinema. The pan flute becomes a mesmerising leitmotif, while “Deborah’s Theme” is a harrowing melody. Perhaps it’s only rivalled by his “Love Theme for Natalia” from the sublime Cinema Paradiso (1988), but that’s just nitpicking at this stage.

The writing team behind the adaptation of Harry Grey’s novel, The Hoods, also deserves recognition. Leonardo Benvenuti, Piero De Bernardi, Enrico Medioli, Franco Arcalli, Franco Ferrini, and Sergio Leone all played a part in transforming the original story into a hefty screenplay. Together, they effortlessly develop each character on screen. Their 317-page script subtly conveys the passage of time through dialogue, eschewing the need for large, intrusive timestamps. Plot information is revealed organically, without the viewer even realising it—a testament to the script’s lack of jarring exposition.

There’s an expression that describes how there are three versions of every film: the one that exists on the page, the one that’s filmed, and the final work painstakingly crafted in the editing suite. This statement couldn’t be truer for Leone’s masterpiece. Over an entire year, he and editor Nino Baragli crafted an interwoven triptych, where boundaries of time and space completely melt away. The ringing of a telephone is all they need to move across the narrative, showcasing the true power of cinema as an art form.

Poetic visual matches facilitate these leaps across time. A peephole, or smoke curling from a vent, becomes an opportunity to teleport Noodles to a different period in his life. It’s a noteworthy stylistic choice that Leone forgoes timestamps: he trusts his audience to be drawn into Noodles’ memory. Leone seems to grasp that we might be unsure of exactly when these formative moments transpired in our own lives. All we can know for sure is that they happened—or can we even be certain of that?

There’s a great deal of ambiguity concerning the truth of Noodles’ perspective; after all, he’s a former opium addict. Certain sequences have a dreamlike quality, leading us to question: how much of this story is real? How much of it is a drug-induced fantasy? Could the scenes set in 1968 all be figments of his imagination? The fact that we first encounter Noodles in a dingy opium den, with the film’s final scene returning to this moment, hints that we might be trapped within a boundless dream. In this dreamlike reality, Noodles is free from the burden of regret.

In this respect, Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America is reminiscent of John Steinbeck’s The Winter of Our Discontent (1961). Both narratives feature protagonists who dream of striking it rich, with each man attempting to achieve wealth through immoral methods. However, both our heroes are haunted by the path they take, and the money they amass becomes worthless; consumed by guilt and regret, they yearn for escape. Why else would one of the richest men in New York reside in the squalor of an opium den?

It is only there that he can truly live out his dreams, a stark contrast to the ruinous life he has built for himself. In John Steinbeck’s novel, protagonist Ethan Allen Hawley declares: “People who are most afraid of their dreams convince themselves they don’t dream at all.” Noodles, however, has twisted his dreams into a tangible reality, one he now desperately tries to convince himself is a mere illusion. To escape his self-inflicted misery, he must rediscover the power of dreaming, supplanting the real world with a pleasant fiction.

This is arguably the most haunting element of Leone’s film. The characters we’ve come to know so deeply become shells. Ghosts. Phantoms that belong to the past. They’ve emptied themselves of their humanity and scooped out their innocence for the promise of a prosperous future away from the streets. Only years later will they all realise that they were happiest, and most human, when they were boys.

Leone’s final film encapsulates everything I adore about cinema. It brims with emotion, complex characters, and weighty themes. It offers a detailed examination of a life squandered. Intelligent writing, masterful editing, and skilful cinematography all coalesce to convey the ineffable, transient experiences that shape the human condition. Perhaps, above all else, it’s the ending. An odyssey as long as this one can be captured in a single image: a man’s smile. A smile for a life he lived and half-imagined, a smile for loves he never truly knew, and a smile for the friends he has lost, the boys he can only see again in his dreams.

ITALY • USA | 1984 | 229 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • ITALIAN FRENCH • YIDDISH • HEBREW

director: Sergio Leone.

writers: Sergio Leone, Leonardo Benvenuti, Piero De Bernardi, Enrico Medioli, Franco Arcalli & Franco Ferrini (based on ‘The Hoods’ by Harry Grey).

starring: Robert De Niro, James Woods, Elizabeth McGovern, William Forsythe, James Hayden, Burt Young, Tuesday Weld, Scott Tiler, Rusty Jacobs, Brian Bloom, Adrian Curran, Jennifer Connelly, Noah Moazezi & Joe Pesci.