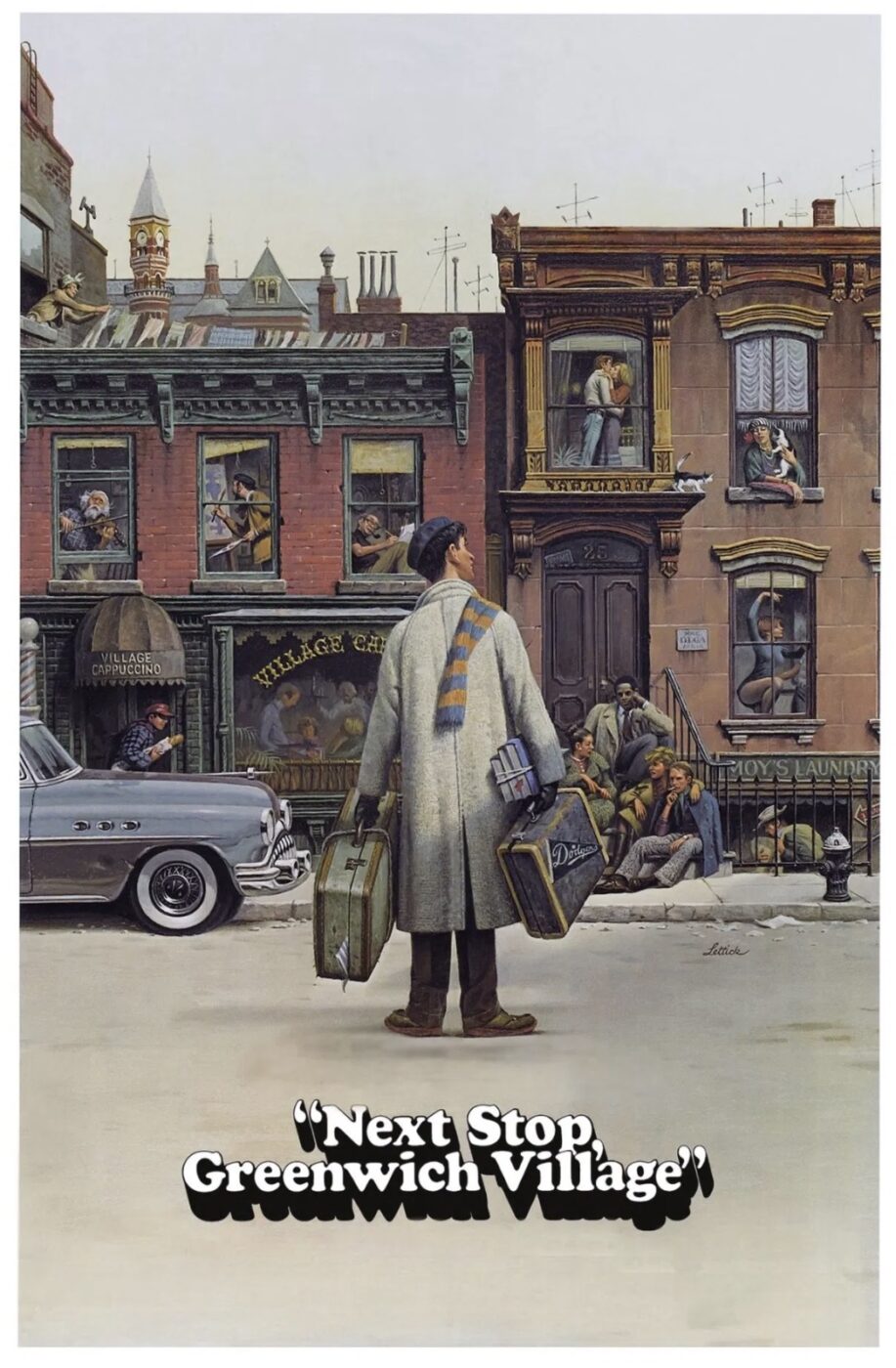

NEXT STOP, GREENWICH VILLAGE (1976)

The ups and downs of life as experienced by a group of aspiring young artists in New York City during the 1950s.

The ups and downs of life as experienced by a group of aspiring young artists in New York City during the 1950s.

There is a distinct melancholy to the cinema of the mid-1970s, a specific frequency of disappointment that vibrates through the era’s best work. By 1976, the New Hollywood revolution had begun to audit its own myths, and Paul Mazursky arrived to perform the autopsy.

Next Stop, Greenwich Village treats the past not as a lost home, but as a test laboratory—a place where the chemicals of youth, ambition, and delusion were mixed with volatile results. Mazursky, a director who occupied a singular space between the raw improvisational energy of John Cassavetes and the commercial wit of Neil Simon, uses the 1953 Greenwich Village setting to interrogate a persistent fantasy: that the artistic milieu is, by nature, a superior plane of reality.

The film’s quiet provocation isn’t the cliché that “artists are fake”, but something harsher and more accurate: that the artist’s primary instrument—language—can become the most refined way to avoid the real. While the film dresses itself in the costume of a period comedy-drama—the Jewish boy leaving the suffocating gravity of Brooklyn for the oxygen of Manhattan—it refuses to play by the rules of nostalgia. There are no golden hazes here; New York’s winter light is grey, the apartments are cold, and the bohemian dream is teeming with cockroaches.

The protagonist, Larry Lapinsky (Lenny Baker), arrives in the Village believing he’s escaping performance, only to find himself in a theatre of a different kind. He survives this environment through a particular defence: wit. He jokes, he frames, he editorialises. He keeps reality at a manageable distance. In the hands of a lesser filmmaker, Larry’s constant humour might be treated as mere charm or a neurotic tic to be cured. Mazursky, however, treats it as a necessary immune system.

Technically, the film mirrors this psychological state through what might be called a metabolic approach to craft. Cinematographer Arthur J. Ornitz shoots the Village with a handheld intimacy, yet there’s a disciplined restriction to the palette—browns, greys, and deep shadows that suggest spaces used for hiding rather than display. The camera creates a “livable distance” from the subject: close enough to register the micro-expressions of social panic, but rarely invading the actor’s space with a confessional close-up. It’s an optical grammar that respects the characters’ armour. Similarly, Richard Halsey’s editing cuts on actor rhythms rather than plot beats. The overlapping dialogue turns language itself into both weapon and shelter.

This creates a tonal mixture that stops looking like an aesthetic choice and starts looking like anthropology. Comedy and tragedy are simultaneous temperatures in the same room. A mother can be oppressive and loving in the same breath; a friend can be suicidal and mundane in the same afternoon. The bohemian circle Larry joins functions as a repertory company of defence mechanisms. Robert (Christopher Walken, in a performance of feline, alien charisma) wields Blake quotations like aristocratic credentials; Bernstein deploys sarcasm as prophylaxis; Anita retreats into a fragility that demands protection. Each has found their own dialect of evasion.

Larry’s distinction is that his method—the compulsive joke, the editorial aside—is transparent enough to be called out. When a classmate challenges him—“Is everything a joke to you?”—the moment isn’t soothed but weaponised by the acting teacher: “See, you’re joking right now, right?” The accusation lands because it’s true. But the film refuses to treat this as simply a character flaw to be overcome. Instead, it asks a more unsettling question: what if the joke is the only viable response? What if sincerity, uncut, would be unliveable?

This ethic is revealed most brutally in the film’s “hinge” sequence: the acting class. On paper, it’s a classic narrative device—teaching the theme by teaching acting. In practice, it becomes a moral X-ray of the bohemian myth. The teacher, an imperious guru figure, preaches a theology where authenticity equals suffering. “Bleed for your art,” he demands. In a film that’s already brushed against self-harm and clinical depression, the phrase lands as more than macho rhetoric; it’s a grotesque transmutation where the rawest sign of despair is converted into an artistic credential. Mazursky allows the line to incriminate itself. The teacher’s error is metaphysical: he treats defence as failure, whereas the film treats defence as survival. He mistakes “contact” for “wounding.”

Here, the film engages in a fascinating philosophical pivot, rejecting an Aristotelian hierarchy where comedy is “lower” than tragedy in favour of a specifically Jewish logic of laughter. The film’s Jewishness isn’t cosmetic; it’s structural. It’s present in the mother’s smothering guilt, in the food that serves as emotional currency, and in the rhythm of the wit itself—inherited, rapid-fire, self-deprecating yet resilient. In this framework, wit is wisdom, and irony is the only sane posture before an unbearable real. Not “mockery”, but cognitive mercy—a way to keep going. That’s why the film’s jokes feel like proximity rather than exit. They don’t erase the tragedy of a suicide attempt or a broken dream; they let tragedy remain visible without becoming total.

The proof of this logic arrives in the film’s most indelible image. When Anita’s suicide attempt shatters the day, the group doesn’t freeze in solemnity. Instead, they improvise a conga line on the pavement, dancing their way to her flat. It’s a moment that’s grotesque, absurd, and tender at once: comedy as the only bearable distance from catastrophe. This moment crystallises Mazursky’s entire project. The bohemian circle becomes a substitute family, yes, but it’s not automatically wiser or freer than the family left behind in Brooklyn. It has its own control systems, its own status games, and its own predations.

It’s worth noting what the film refuses to show. For a movie about artists, there’s a conspicuous absence of “art” as an object. We never see a painting worth staring at; we never hear a poem that redeems the room; the plays are merely scenes to be parsed for subtext. If Mazursky had shown us a masterpiece produced by one of these characters, the milieu would claim a retroactive nobility—the suffering would be justified by the output. Mazursky withholds that permission. In this Village, art is primarily social grammar—a way of speaking, classifying, and legitimising oneself—more than something that actually happens.

Larry, however, is an artist of a less flattering, more durable kind: a worker. While the others rehearse a lifestyle, Larry rehearses a craft. He auditions. He repeats. He gets notes. He fails. He works at a health food store not to gather material, but to pay rent. This distinction becomes sharpest in the film’s resolution, which splits the characters into two destinies. Some remain in the Village loop or drift towards Mexico, which represents the fantasy of “a place where you can live”—flight without a project, motion as anaesthetic. Larry goes where he has to go: Hollywood.

His departure isn’t framed as selling out, nor as a dream of glamour, but as the logical terminus of work. Mexico is for drifting; Hollywood is for industry. It’s the place where you’re held to what you can do, not who you pretend to be. The Village, then, was never the destination. It was a probationary zone, a staging area where adulthood is rehearsed, postponed, and occasionally mistaken for freedom.

Shelley Winters commands the film’s emotional centre with a performance of high-wire intensity that threatens to tip into caricature but never does. She can dominate a rent party with swing-dancing ferocity one moment and collapse into operatic grief the next; both registers feel utterly sincere because Winters locates the thread connecting them: a desperation so total it can only express itself through extremes. She is the original performer, the one from whom Larry learned that love and suffocation can be the same thing.

Next Stop, Greenwich Village endures because it’s that rare period piece that refuses to flatter the past. It suggests that the “authenticity” everyone is chasing is largely a myth, and that the masks we wear—the jokes, the poses, the deflections—aren’t necessarily lies. Sometimes, they’re the only things that let us tell the truth. Mazursky doesn’t tell you how to live. He shows you how people actually do: by improvising, by armouring, by breaking, and by laughing—not because laughter is a denial of reality, but because reality, unmediated, would be impossible to inhabit.

USA | 1976 | 111 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Paul Mazursky

starring: Lenny Baker, Shelley Winters, Ellen Greene, Lois Smith & Christopher Walken.