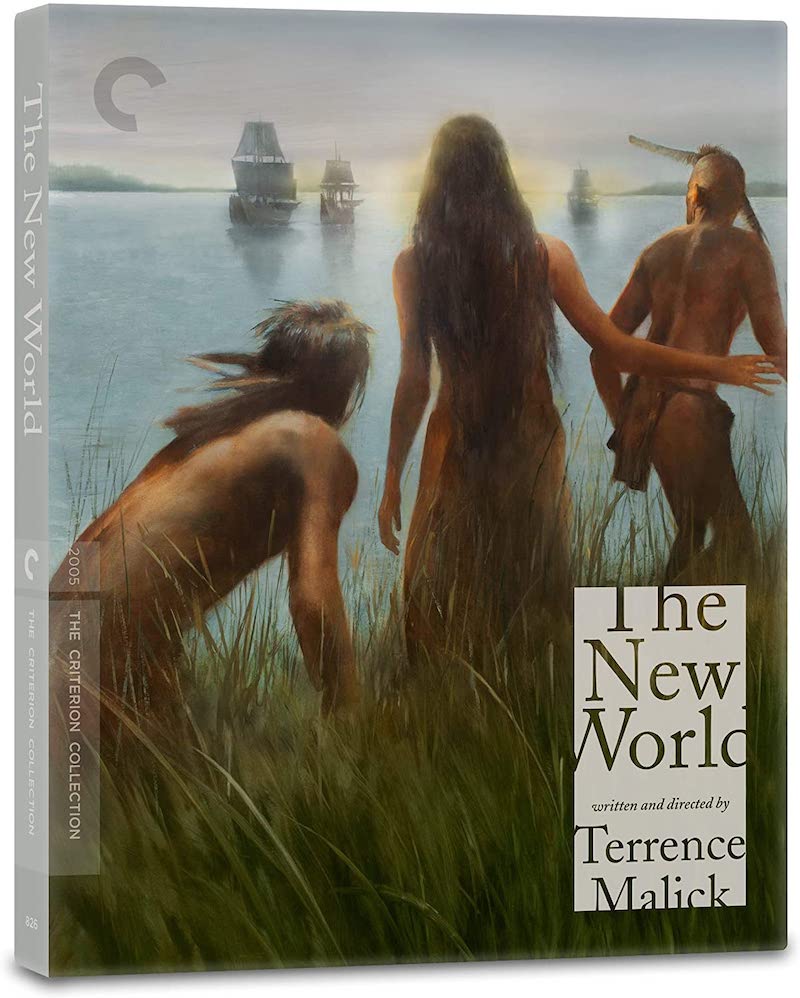

THE NEW WORLD (2005)

The story of the English exploration of Virginia, and of the changing world and loves of Pocahontas.

The story of the English exploration of Virginia, and of the changing world and loves of Pocahontas.

Virginia, 1607. British colonists make landfall and set up a small settlement on the shores of the ‘New World’. One of their number, professional soldier John Smith (Colin Farrell), is spared from his death sentence by the leader of the expedition and given a chance at a new life. The colonists immediately draw the attention of “the naturals”, both curious and suspicious of the new arrivals. Although they exist in peace for a time, with Smith and native princess Pocahontas (Q’orianka Kilcher) falling in love, conditions worsen for the settlers, driving them to desperate measures. Hearts are broken, lives are lost, continents crossed, all told with writer-director Terrence Malick’s imitable style.

What defines a Malick film? Is it the beautiful cinematography, gliding and circling, probing close to both people and nature? Is it the whispered voiceover of enigmatic phrases like “I should tell her. Tell her what? It was just a dream. I am now awake.”? It is the slow, slow, slow pace? Possibly, but these are stylistic choices, of course, nothing more. The decision that really seems to define Malick’s 21st-century period, more than anything else, is his decision to eschew the traditional rules of storytelling, or perhaps to eschew interest in them. Events don’t lead to each other, they simply happen after each other, and this inclines us to form some kind of causal connection between them, which in turn inclines us to divine meaning. All this makes The New World a struggle to follow, especially if you find your attention has drifted for too long.

As the initial protagonist, John Smith, Colin Farrell is almost too-perfectly cast as a smoldering rogue. With a frequently open chest, long curly hair, and a just-rugged-enough beard, he looks every inch the hero of the bodice-ripper this film was badly marketed as. He’s Poldark for intellectuals. It’s easy to see why Q’orianka Kilcher’s Pocahontas is beguiled by his stoic manliness. He’s also effortlessly convincing at the times when he’s a complete shit—the film making the bold claim that smouldering rogues are normally pricks, while friendly men turn out to be good and loving and are a better choice of romantic partner should you want a happy life.

The fourteen-year-old Kilcher herself is given little to do other than be a beautiful princess and express simple emotions (What? An underwritten female character? Never!), although she equips herself well when her storyline develops complexity in the final hour. The other function she serves is to remind us that, although it might be tempting to suggest this film’s a realistic portrayal of the Pocahontas story (even if historically inaccurate), her perfectly straight and luminous white teeth make it clear this is still a movie.

Final-hour star, Christian Bale, gives a quietly impactful performance as a good man, John Rolfe, occasionally breaking out his million-megawatt movie star smile that he never seems keen to fully exploit—lest people forget that he’s a proper, serious actor. Circling around them are Malick’s usual great actors given little to do: Christopher Plummer, Wes Studi, David Thewlis, Ben Mendelsohn, Noah Taylor, Eddie Marsan, and Jonathan Pryce (who joins the special Malick club of great actors whose parts are cut down to the point of having no lines whatsoever). All these great actors give good performances, but Malick’s screenplay hardly bothers with mere trifles as “scenes” or “conversations”, meaning there’s little for the actors to do except feature in extended montages.

The real hero of any Malick film is, of course, his cinematographer, and the work of the insanely talented Emmanuel Lubezki beguiles you from the first shot. The images, aided by James Horner’s refreshingly pure-hearted score and the excellent sound design, are enough to carry you through the first hour of the extended cut. This is where Malick and his four editors’ slow, slow, slow pacing actually become a virtue. You feel close to nature, existing in the moment of Virginia’s colonisation without artifice; walking in the head-high grass and paddling through the tranquil waters. But the pace becomes frustrating, potentially infuriating, as the colonists move into a winter marked by starvation and disease—static in their fort, no longer exploring new sights. The pace is so slow one would be forgiven for thinking the film had stopped.

The greatest enemy of a Malick film is, of course, Malick himself, and his constant strive for profundity and transcendence. It manifests itself in those perfume ad montages, with the whispery voiceover, that dot an otherwise ethereal creation like ball bearings in an Italian meringue. Malick and his editors come close to transcendency simply through the power of image and sound, then suddenly hammer you with pomposity and ponderousness. It’s the voiceovers that are the real problem; remove them and this film would be 10%, if not 20%, better—or at least, more bearable, depending on your mileage for Malick.

Malick has little interest in connecting events together, so characters go through intense trials and emotions… and we feel none of it. How can we relate and empathise, when we don’t know why they feel like they do? In the final hour, the pace is forgiven slightly by our knowledge there’s only an hour left, and by a new and sympathetic character being introduced. Finally, the emotions kick in and there are some moments when viewers may be inexplicably reduced to a blubbering wreck. Here, Malick is clearly doing a lot right, but it’s tough to nail down what exactly it is.

So what is it all about? Probably colonialism. I mean, it’s literally a film about colonialism. Although, I’m not sure it has anything to say about colonialism, it doesn’t even seem to be particularly against it. It suggests it was a miserable experience for the colonists, if that’s saying something. It also expresses an unusually unromantic view on relationships, suggesting that a practical partnership should be prized before a passionate romance. Maybe it’s not about anything at all, maybe it’s just an experience. I only watched the extended cut, so perhaps it would be foolish to assume the shorter cut is better… but there are few films that benefit from being extended, and I can’t believe The New World is an exception to this rule.

This is a film to wallow in, and if you enjoy that kind of thing you’ll probably hail The New World as a modern masterpiece. For others, the experience will be much like taking a bath: absorbing at first, but then the water becomes tepid, and Malick doesn’t turn on the hot tap again until the final act.

USA • UK | 2005 | 135 MINUTES • 172 MINUTES (EXTENDED CUT) • 150 MINUTES (ORIGINAL CUT) | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • ALGONQUIN • INUKTITUT

writer & director: Terrence Malick.

starring: Colin Farrell, Q’orianka Kilcher, Christopher Plummer, Christian Bale, August Schellenberg, Wes Studi, David Thewlis, Yorick van Wageningen, Ben Mendelsohn, Raoul Trujillo, Brian F. O’Byrne, Irene Bedard, John Savage, Alex Rice, Jamie Harris & Janine Duvitski.