MIRROR (1975)

A dying man in his forties remembers his past: his childhood, his mother, the war, and the recent history of Russia.

A dying man in his forties remembers his past: his childhood, his mother, the war, and the recent history of Russia.

When Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky commenced filming of Mirror in September 1973, he probably felt some relief that production was finally underway. It had taken many years of development for this “resolutely autobiographical film” to finally come to fruition. Composed of memories and dreams, that mixed newsreel footage with colour and black-and-white sequences set in the past and present, all linked through voiceovers (including his father’s poems), it’s often been regarded as Tarkovsky’s most difficult film to get to grips with.

Tarkovsky’s relationship with his parents informed the genesis of Mirror. He’d first written some scenes for it back in 1964, “with only the vaguest idea that the film would be about his mother, his family, the Stalinist thirties, and World War II”, while considering a novella about his childhood experiences of the war during the preparation of his medieval epic Andrei Rublev (1966). He and eventual co-author Alexander Misharin were neighbours and got to know each other socially before Misharin was consulted about the edit of Andrei Rublev, as he recalls in the 2004 interview on this two-disc Criterion Blu-ray.

Still haunted by a recurring dream about the house where he was born and the separation of his parents, Tarkovsky attended a filmmakers retreat with Misharin in February 1968. They shared much about their own childhood memories and decided to turn their nascent ideas into a screenplay, with Tarkovsky’s mother as the central figure of the film. The then titled Confession became a 28-episode proposal, with each of them writing 14 scenes apiece that they swapped between them to then critique and rewrite each other’s episodes.

These scenes gathered together three strands. According to Misharin, the first was a documentary-style interview with Tarkovsky’s mother in her old apartment, filmed with a hidden camera and where “she would be asked various questions covering topics as diverse as the war, her memories of her own mother, art, the meaning of life, feminism, boxing, and UFOs.” Interwoven into this would be the other two strands; acted recreations of childhood memories, and an historical context created through the use of newsreels.

The Soviet state’s Mosfilm studios offered some support for the retitled script, A Bright, Bright Day (often referred to as both A White, White Day, originating from a translation of a line from a poem written by Tarkovsky’s father Arseny in 1942, and as The Bright Day in Tarkovsky’s diaries) but Goskino, the State Committee on Cinematography, rejected it despite assurances from Tarkovsky and Misharin about the unorthodox structure of the narrative. Many of the elements of the completed film can be found in this version of the script, ranging from specific childhood scenes and references to particular newsreels that eventually appeared in Mirror. Much to Misharin’s dismay, instead of fighting to get the film made, Tarkovsky instead committed to a film adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s science-fiction novel, Solaris (1972). He was further offended when Tarkovsky published his own recollections as a short story, A White Day, in 1970.

However, it’s clear from his diary entries between 1970–72 that Tarkovsky couldn’t let go of the project, with an entry in July 1971 stating, “I so want to make The Bright Day, probably it should be mixed, black-and-white and colour depending on memory.” The lack of support from those satellites of state bureaucracy, Goskino and Mosfilm, would continue to hamper much of his work in Russia. Fed up with the production problems he was dealing with on Solaris, Tarkovsky met Goskino’s new chairman, Filip Yermash, in September 1972, and had further discussions with Mosfilm. As Seán Martin notes, it’s possible the publication of A White Day also ignited Mosfilm’s renewed interest in the script. Yermash claims Tarkovsky approached him with a proposal retaining the three levels of acted sections, newsreels and interviews but which also included permission to make changes to the script during production and filming.

For Yermash, “this kind of request went against all principles of film production”, but Tarkovsky was apparently granted this permission. Tarkovsky’s diaries suggest a slightly different story. Yermash asked him to make a completely different film, “involving scientific, technological progress.” Tarkovsky rejected this and insisted he was more interested in “humanitarian questions.” He was asked to submit a plan and a revised script for The Bright Day, a title that Tarkovsky was unhappy with and would change several times during pre-production. Once submitted, a full shooting script would then be approved. Misharin, with whom Tarkovsky’s relationship was back on an amicable footing, recalled that Yermash in fact told Tarkovsky to go and make whatever he wanted.

Nevertheless, by 11 July, a budget and film stock was allocated, and Tarkovsky was ready to make “the most important work of my life.” He had serious doubts about his mother’s participation in the film and whether she would permit the use of an interview filmed with a hidden camera. The interviews were eventually abandoned as they were considered too “direct and unsubtle” and the script underwent continual rewrites both before and during shooting, shifting the emphasis away from an autobiographical work derived specifically from filmed interviews.

Filming was slow, on what was then called Mirror, when it began in September 1973. Tarkovsky’s constant rewrites and his fractious relationship with cinematographer Georgy ‘Gosha’ Rerberg (“he’s rude to people”) resulted in Mosfilm firing off a telegram complaining about the sluggish pace of work. However, Tarkovsky, his cast and crew coalesced as a working community as the shoot progressed and “spent every possible moment together” on production designer Nikolay Dvigubskiy’s meticulously built sets. This summer location shoot included a very faithful recreation, from photographs taken by Tarkovsky’s godfather between 1932 and 1935, of the director’s childhood home, an old wooden dacha in rural Tuchkovo.

The dacha had featured prominently in Tarkovsky’s recurring dream of “my grandfather’s house where I was born right on the dining room table. Pine trees around the house of my childhood. I’m waiting and I cannot wait for this dream where I see myself as a child again. […] I often dream this dream, I’m used to it. And when I see the log walls, darkened by time and the half-open door into the dark passage, I have a dream I know that I can only dream of.” In his commitment to detail and memory, the field in front of the rebuilt house was rented and planted with the white-flowering buckwheat that he recalled from his youth, leaves were painted gold, his mother’s clothes, hair, and poses reproduced.

The memories of certain textures, colours and light were vitally important to him and there are aural and visual motifs that run through most of Tarkovsky’s films, such as the distant barking of a dog, running water, fire, gusts of wind blowing through fields and trees, and reflections in mirrors. These are parceled up here with what Gilbert Adair regarded as a certain mysticism that relied “on ‘Russian’ material textures: fur, milk, green apples, the knotted wood of the dachas and the shifting penumbra of the taiga.” Layered onto this are recurring images and music from Western art, including da Vinci, Bach, and Brueghel. They were all poets in Tarkovsky’s estimation, fellow explorers who could evoke the elusive spiritual meaning to our lives, a quality his father Arseny imparted to him when Tarkovsky requested some of his poems to be included in the film.

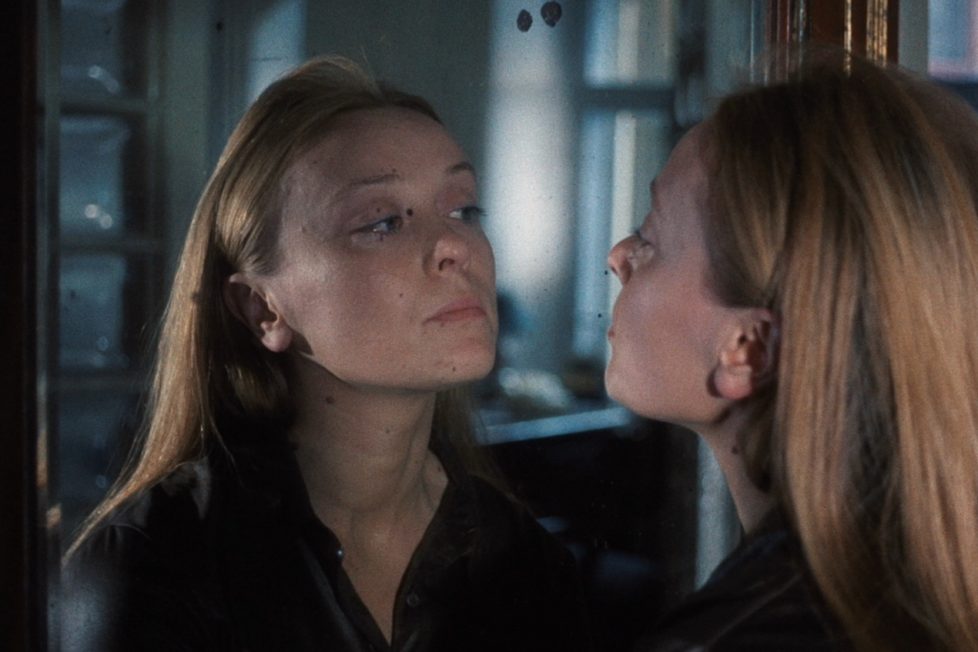

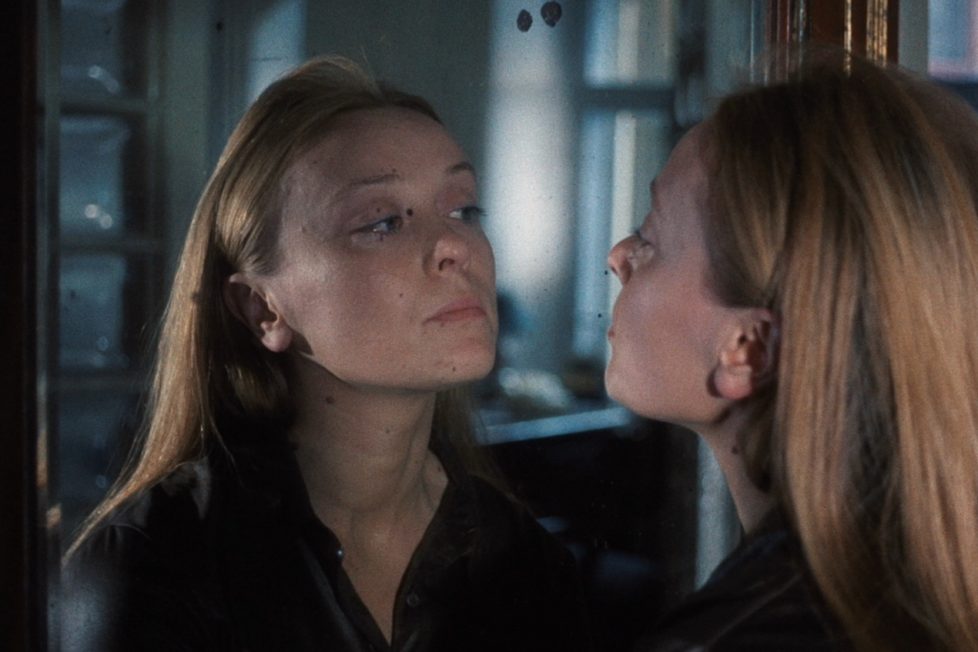

Originally, in 1970, he’d entertained some thoughts on casting Swedish actor and frequent Ingmar Bergman collaborator, Bibi Andersson, as the mother and wife to the film’s unseen narrator. However, having cast Margarita Terekhova, during the location filming at Tuchkovo he was so satisfied with her work that he started writing additional material for her in the film’s contemporary settings when they returned to the studio. She bore an uncanny resemblance to his own mother Maria, who eventually played the mother as an older woman in the film and was one of several family members to make appearances, including his second wife Larisa and his stepdaughter. In doing this, he made Mirror a very personal film, evoking a primal sense of his formative years.

The problem for Tarkovsky was that his edit of Mirror was a mess and he struggled to find the core of the film’s meaning by following the progression of scenes as he’d scripted them. Allegedly, there were, at some point, 20 different edits and Tarkovsky despaired that the edit was “hopeless” and “going really badly.” In March 1973, Nikolai Sizov, deputy chairman of the State Committee for Cinematography, saw early edits “and he had no idea what it was about either” and, after after the screening of various edits, Yermash rejected the film in July and demanded cuts to try and make the film more comprehensible and less dependent on mysticism.

Tarkovsky spent much time shifting entire episodes of the film around in the edit with editor Ludmila Feiginova before he hit upon its poetic, non-linear structure and by August he refused to make any further cuts. Cinema, for him, was a way to “capture and express time” and, certainly, Mirror achieves this without compunction. However, getting Mirror screened would then prove to be a greater obstacle. Tarkovsky was particularly hurt by the rejection of the work by his own colleagues in the film industry, and when the film was officially declared a failure, it was released with little fanfare in Russia in April 1975. Attempts to get it distributed internationally and to send it to Cannes were stymied by Goskino. However, despite its limited Russian release, co-writer Misharin and Tarkovsky’s wife Larisa reported full houses at cinemas showing the film.

While it didn’t receive a release in Europe until 1978, it provoked an intense and profound reaction in its Russian audience, who recognised something of their own spiritual biography in the film. In the superb documentary A Cinema Prayer, included on this set, Tarkovsky recalls how an argument about the film’s meaning and symbolism, between film critics after a screening, was eventually disrupted by a young cleaner, “a simple woman” who said it was quite clear what the film was about. Of the film critics, he opined that, “the more they talk, the less they understand”, and he appreciated what she told them: “It’s very simple. A man fell very ill and thought he might die. He remembered all the terrible things he’d done to others and wanted to apologise. That’s all.” A Cinema Prayer also shows Tarkovsky playing this unseen patient in a number of frames removed from the final edit. It’s an uncanny foreshadowing of the cancer that finally took Tarkovsky’s life as he was editing his last work The Sacrifice (1986). In Mirror, the patient’s doctor believes his malaise can be attributed to “conscience, or memory” and while we only see the patient’s arm and hand, upon which a bird has settled and then takes flight when it is released, there is again a connection to one of Irina Brown’s photographs of the ailing Tarkovsky conversing with a bird during his last days in Paris. The theme of flight occurs throughout Mirror and appears in several of his other works.

Indeed, the cleaner was right. The non-linear structure keeps this revelation almost to the end of the film but it clearly fulfills Tarkovsky’s notion that he wanted to explore states of extreme tension for his characters as they attempt to resolve their spiritual crisis. Mirror is puzzling and enigmatic but, as Vida Johnson and Graham Petrie argue, initially the film may have been damned as baffling and incoherent by Western critics because they were unable to connect with some of the historical and cultural context. Johnson and Petrie quite rightly call it “an autobiography of the artist, and a biography of two Soviet generations (Tarkovsky’s and his parents’) within a wide ranging context of Russian, European, and world history.” Tarkovsky’s technique is to use “dreams, memory, time, and art itself” as a way of navigating through these biographies. Simultaneously, he makes the film ravishingly beautiful and as such it’s a sensual as well as an intellectual experience.

The film begins with a striking prologue, set in the present day. A young boy, Ignat (the son of the off screen narrator Alexei is played by Ignat Daniltsev who also appears as the adolescent Alexei in flashback) turns on a TV and watches a documentary where a hypnotherapist cures a teenager of his stutter. Many have seen this as a declaration, when the teenager is able to speak clearly after some treatment, of Tarkovsky’s own wish to speak as clearly across time. From here the film flits between different time periods and, through the unseen adult Alexei’s voice (Innokenty Smoktunovsky) and the poems by Tarkovsky’s father, we are first presented with a return to Alexei’s childhood home, the dacha outside which his mother Maria (Terekhova) sits on a fence, watching the fields for the return of her husband from the war. She meets a passing doctor (a brief part written especially for one of Tarkovsky’s favourite actors, Anatoly Solonitsyn) and the encounter seems to stir elemental forces across the fields and outside the house.

From the outset we’re never sure that these are either the adult Alexei’s memories or recollections his mother has passed onto him. Perhaps it’s best to accept that there are many voices entangled here, given the images are also specifically matched to readings of Arseny Tarkovsky’s poems on the soundtrack. Certainly, this sequence establishes a growing sense that Tarkovsky seeks some sort of catharsis by entering the house that dominates his recurring dream and was the origination of Mirror. It also briefly foreshadows dreams and flashbacks that appear throughout the film’s structure by intercutting it with a moment where Maria washes her hair in a room which starts to disintegrate, then looks at her reflection in a mirror and sees an old woman, her older self, looking back at her, and a shot of a hand being warmed by a fire that is eventually revealed as belonging to Alexei’s childhood sweetheart. The symbolism of fire reoccurs throughout: from the viewpoint of Maria and the younger Alexei we see a barn on fire during the sequences at the dacha (like many images, it is first seen reflected in a mirror) and, later, the story of Moses and the burning bush is part of the conversation between the adult Alexei and his wife Natalia (also played by Terekhova) in one of the film’s contemporary scenes.

These contemporary scenes often contain prompts, leading to either a newsreel, to give historical context, or a flashback or dream that is partly Alexei’s memory and Maria’s biography. The adult Alexei’s phone conversation with the older Maria (played by Tarkovsky’s mother Maria Vishnyakova) triggers a tremendously evocative flashback. When she mentions the death of her printing works colleague, Lisa (lla Demidova), Tarkovsky conjures up Maria’s slow motion, monochrome arrival in the rain, running through the labyrinthine printing works and captures her desperation to check on a possibly blasphemous typo in a recent folio. Seán Martin sees the endless, drab, dilapidated corridors of the works “hinting at the era of Stalin’s terror”, the Great Purge of 1936–38 in which at least 750,000 people were executed and many were banished to the gulags.

The sense of history weighing down on Tarkovsky’s characters is underlined in the use of newsreels. Another contemporary sequence, where Alexei and his wife Natalia are arguing while their Spanish emigre friends reminisce in the next room, introduces a set of such reels. The first reel of bullfights and Spanish refugee children being evacuated to Russia suggests a longing to return to their own country, the next is a record breaking Soviet balloon ascent of 1934 which evoked a tragic sense of loss with Russian audiences at the time, who knew that all the aeronauts died in the attempt. These newsreels accumulate, impressing upon the autobiographical nature of the film a sense of history and time passing.

During a sequence set on a firing range where the young Alexei and other boys are being given shooting practice, one of the boys, Asafiev (Yuri Sventkov), walks up a hill overlooking the snowy landscape, where Tarkovsky homages Pieter Brueghel’s 1565 painting ‘Hunters in the Snow’. As he progresses, reaches the top of the hill and looks out, a newsreel of the Soviet crossing of Lake Sivash in 1943 is intercut. Seán Martin suggests that Asafiev “seems to ‘see’ [the newsreels]… from where he is standing” and the intercutting and the boy’s body language “brilliantly brings together the spheres of the personal and the historical.” Tarkovsky both implies a sense of the troops’ heroic efforts and of the futility of war in his use of the Lake Sivash footage and his editing implies that such events live on just below our consciousness. However, if a viewer is unfamiliar with the historic events these newsreels impart then admittedly some of this context is unknowable without some specific research into the film’s meaning beforehand. However, they do conjure up the inevitability of history threaded throughout the film, the idea that the passage of time cannot be stopped, whether those moments record loss or elation.

It’s a film full of ghosts, visions, and reflections. The sets are decorated with many mirrors and characters often look into them, searching their reflections for the effects of time upon their physicality, perhaps, or merely hoping that they can return to the past and connect with it spiritually. Alexei’s missing father appears briefly and then vanishes, recalling Tarkovsky’s own estrangement from a father whom, as a child, he obviously loved. The father also features in a strange scene where Maria is shown levitating above their bed. Again, this is a common image in Tarkovsky’s films, and the gravity defying scenes in Solaris and The Sacrifice come to mind. It’s suggested by Peter Green that they are symbolic of consummated love. Maria’s mother appears not only as a reflection memorialised in a mirror but briefly turns up in person at the door of the flat in a contemporary sequence. She interrupts young Ignat as he reads a letter from Pushkin to the philosopher Chaadeyev, a meditation on Soviet destiny written in 1836, to a mysterious woman (Tamara Ogorodnikova) sitting and drinking tea. The mysterious woman disappears, the heat from her cup of tea evaporating from the table as a fleeting clue she had ever been there. She reappears at the adult Alexei’s deathbed and remains just as uncanny a figure during a brief scene where the film’s overarching sense of Tarkovsky’s “perpetual pity” for his family and friends and “my feeling of duty left unfulfilled” reaches its culmination.

Mirror, a sumptuous tapestry of light and sound, remains enigmatic and is a continuation of Tarkovsky’s themes about nature, faith, art, home and history. Here, those themes are discussed on a more personal level and are given specific resonance with his own biography. It’s no doubt that this biography was recognised as a universal experience by some Soviet audiences who went to see the film, judging by their reaction to it. His desire to reconcile with the past, carried on the winds of time, is encapsulated in the glorious final scene as the old Maria (Vishnyakova, again), transfigured in dream, occupies the same space and time as the young Alexei and his younger sister. As Bach’s uplifting music swells, the aged mother takes Alexei’s sister by the hand and turns away from what appears to be the ruins of the dacha and continues through the fields, watched by her tearful younger self who looks upon her as yet unborn children. It’s not only a recognition of the influence of Tarkovsky’s own mother but also a sublime expression of time and memory as a spiritual realm connected to multiple lives.

SOVIET UNION | 1975 | 107 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | RUSSIAN • SPANISH

I am indebted to the following sources: Gilbert Adair, ‘Zerkalo (Mirror) review’, Monthly Film Bulletin Vol. 47, №552, ( BFI, January 1980) • Peter Green, Andrei Tarkovsky: The Winding Quest, (Palgrave Macmillan, 1993) • Vida T. Johnson and Graham Petrie, The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, (Indiana University Press 1994) • Seán Martin, Andrei Tarkovsky, (Kamera Books, 2011) • Andrei Tarkovsky, Time Within Time: The Diaries 1970–1986, (Faber 1994) • Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting Time: Reflections on the Cinema, (University of Texas Press, 1986).

director: Andrei Tarkovsky.

writers: Aleksandr Misharin & Andrei Tarkovsky.

starring: Margarita Terekhova, Ignat Daniltsev, Larisa Tarkovskaya, Alla Demidova, Anatoly Solonitsyn & Tamara Ogorodnitkova.