LEAVING LAS VEGAS (1995)

An alcoholic screenwriter who lost everything arrives in Las Vegas to drink himself to death... but forms an uneasy friendship and non-interference pact with a prostitute.

An alcoholic screenwriter who lost everything arrives in Las Vegas to drink himself to death... but forms an uneasy friendship and non-interference pact with a prostitute.

A man with nothing left to lose, hellbent on drinking himself to death, who can’t help but be liked by others even when he’s a perpetual screw-up. A hooker with a heart of gold who tends to his needs, all while having to stomach the emptiness in her life. Ben Sanderson (Nicolas Cage) and Sera (Elisabeth Shue) would be walking, talking clichés in any other film. In Mike Figgis’ Leaving Las Vegas, they are transcendent, rising above tropes and forming an unlikely partnership that was never built to last. But that’s exactly why it’s beautiful.

Figgis, who adapted the film’s screenplay from the novel of the same name by John O’Brien, doesn’t shy away from how messy these characters’ lives are. When Ben is drunk, he can be creepy, rude, bizarre, and generally off-putting. Sera is more put-together, refusing to wear her scars so openly, but that doesn’t mean they don’t exist (and I’m not referring to the ones inflicted on her by her Latvian pimp Yuri Butsov [Julian Sands], though that dynamic certainly isn’t helping things). Neither of them can quantify, understand, or articulate their emptiness, but you still feel it just as acutely as they do throughout the film.

Leaving Las Vegas is relentlessly brutal, even in its funniest moments. There’s quite a bit of comedy here when Ben gets up to his drunken antics, like recording himself making sexual comments about a bank teller as he stands just a few feet away from her. But these scenes are also endearing, and tragic, too; tragic most of all. You feel that you go on a journey through moving circumstances, but these characters don’t really grow. They don’t even regress, exactly. They just continue along a trajectory that feels inevitable, only this time they have each other, which begins when Sera accepts Ben’s offer to pay her for sex. Instead they just talk—Ben’s alcoholism doesn’t exactly make him a reliable lover—and discover a genuine rapport between one another.

The initial jumping-off point of this complex relationship doesn’t strike me as completely genuine, given how quickly Sera longs to look after Ben, but it’s worth noting that their connection is hardly formed on the basis of attraction. She pities him and looks after him, finding a deep sense of purpose in replenishing someone else’s spirit, since she cannot bear to look inward and afford herself the same generosity. The film’s central dynamic becomes tantalising when you’re forced to reckon with the unique borders and openness of their love, and how easily it extends beyond the simplistic boundaries of the vast majority of romantic and sexual relationships.

In almost any other film, the roughly 15-minute sequence kick-starting the film, where Ben burns all of his remaining bridges and his belongings before heading to Vegas, would involve leaving a trail of destruction. Ben would give the people in his life—soon to be complete strangers—a piece of his mind, whether they deserve it or not, underscoring the fact that he’s oh-so-far from perfect. And there would be a perverse sense of satisfaction in these interactions, however cruel they might become, where one gets to bask in a character throwing aside any notion of politeness and loudly announcing all the things that remain unsaid in everyday life. It would be unapologetically vicious. Leaving Las Vegas’ opening sequence is none of those things. Ben does make a terrible impression on strangers and long-time acquaintances alike, but in the end it’s pity, not disgust, that makes up their strongest impression of this wounded man.

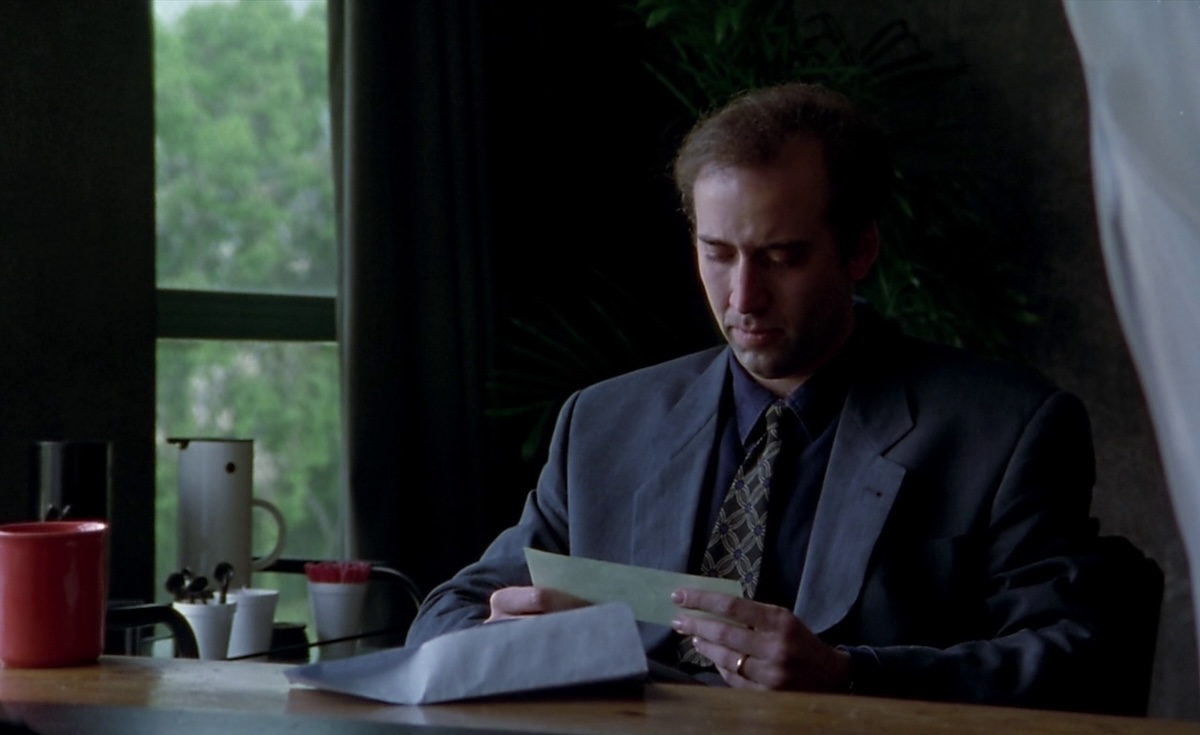

In many cases it’s a kind of pity that is so disarmingly genuine that you can’t help but sympathise with these people, too. The scene where Ben is fired from his job is one of the strongest moments in the entire film, where he tearfully reflects to his boss that his severance package is too much and isn’t warranted given how he’s behaved. His boss reciprocates that affection, telling Ben that they all really liked him, as if he has already left the building and company forever. As if he’s already dead. It’s partly true, since he’s become another person entirely since alcoholism ravaged his personal and professional life. You feel the history and tenderness between both men in mere seconds, with Figgis never letting the tragedy of this story get in the way of just how much love courses through it.

He adores these characters, tenderly observing their wounds and how they deepen. In many of the movie’s best scenes, it’s as if his presence—and that of O’Brien, who committed suicide just weeks after signing off on the film rights, and whose loved ones viewed his novel as a suicide note—is looming just beyond the borders of this drama. Just like Ben’s boss, it’s as if the writer-director is reflecting on these characters’ lives as though they’re foregone conclusions. Everything aches in this movie, even love.

With nothing left to do but go about their daily routines, this time with someone to come home to each night, Ben and Sera wander through the Vegas strip like ghosts. They know this about themselves, too. Ben understands that there are limits to his bond with Sera; if she’s absent from his life, it will be no great tragedy. A reckless nosedive towards oblivion has made him unapologetically selfish. Sera has been afforded some grace on Figgis’ part not to include tragic backstories involving an absent or abusive father figure, or the many other tropes that usually creep into stories about sex workers to try and justify presenting them as damaged goods. That label is tacked onto Sera by other people at the absolute worst of times, where it’s impossible not to despise the strangers who so offhandedly dismiss or insult her.

Both her and Ben know that they aren’t well-liked. Those that know them well have an understanding of their reputation, which is never good (except in a monetary sense for Sera), and strangers usually regard them with distaste. These characters look in the mirror and don’t fully understand themselves, with Shue’s voice-over narration throughout the film underscoring her need to make sense of her recent past in an attempt to uncover who she really is. Ben’s concept of time has become a hazy blur that he shies away from through being completely hammered at all times, unmooring himself from everything and everyone. Did he drink because his wife left him, or did she leave him because he kept drinking? He no longer knows the answer. The past is a mystery for Ben, the future a certainty: a slow crawl towards oblivion punctuated by heavy drinking.

Ben and Sera recognise that they are playing fast and loose with their lives, always carrying the risk of coming home bruised and bloodied each night. Either of them could die at any moment, but they will never change themselves for one another. It’s a strange and toxic relationship that is remarkably honest; Figgis makes the right choice to forgo agonising and pointless conversations where the pair try to make each other see the error of their ways, or skewer the hypocrisy of such statements.

A lack of acceptance continually drives them back to one another. Nestled in the comfort of each other’s arms, both of these characters get to suffer together. It’s entirely possible that improved self-esteem or better circumstances would have ensured that these two lost souls never cross paths. But terrible fortune has brought them this oasis, so they stay shackled to their bleak environments to bask in its brief glory. This chance at salvation is simply a mirage in the long run, but it would be too unkind to Sera to have her discover that right away.

Ben knows it fully. That’s why he doesn’t care if he offends or betrays Sera. Of the misfortunes that befall them, the most cutting of them all occurs when a landlady tells Sera that she often comes across screw-ups in her line of work, and that her and Ben must leave come the following morning. It’s disarmingly ruthless, a blindsiding, cutthroat dismissal of the sum total of another person’s being, rounded out by a fake smile and a cheery goodbye. But if this were to happen to Ben, he would laugh it off, well aware that concerns over ego or trust in other people are all so fleeting in this late stage of his life, where he whittles down his savings with little care, assured in the belief that he will die before he can ever go bankrupt.

Even though Sera isn’t present in the film’s first 15 minutes, it doesn’t take long to get used to her routine, behaviour, and inner turmoil. What’s more remarkable is how seamless it is to watch her gradually become the film’s main character, where we wind up following her point of view more often than Ben’s. The only downside of this approach are the occasionally contrived moments of pitch-black tragedy that ensnare Sera. An act of violence late in the film is tastefully composed in some respects, but there are still individual lines of dialogue and mannerisms present that are very hard to buy into. On a first watch years ago, the scene and its implications struck me as a limp effort at eliciting shock and misery, but now the situation doesn’t seem nearly so unrealistic, even if some aspects of its presentation resist that notion.

But despite a few odd moments throughout Leaving Las Vegas that are either cheesy, obvious, or distasteful, they’re a very small portion of the grand portrait of despair and connection that the movie forms so effortlessly. These are the best performances I’ve ever had the pleasure of witnessing from Cage or Shue, with the former having clearly done his research in his attempts to mimic the speech and movement patterns of an alcoholic. For Cage, this process involved getting continually drunk for two weeks while a friend video-taped his behaviour, then studying the material meticulously. Ben’s helpless, sunken eyes and the black bags formed underneath them tell their own story. It takes more time to recognise that the same emotional highs lurk in Shue’s performance. But once you come to understand this character fully, the American actress is captivating for every second she’s on-screen.

This was a low-budget movie that was made without filming permits and shot on the Vegas strip, with some scenes being filmed in just a single take so as not to attract the attention of police officers. The film’s gritty visuals are so well-calibrated to the personalities of this fatalistic duo that, upon watching it, you would never guess for a second that Figgis was constrained into adopting this guerrilla style of filmmaking. Leaving Las Vegas transcends its budgeting limitations, the tropes that serve as its jumping-off point, and the borders of a typical love story, with a narrative that reaches for the stars and cries out alone in the booze-drenched gutters, unearthing beauty and pain in equal measure.

USA | 1995 | 111 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • RUSSIAN • LATVIAN

writer & director: Mike Figgis.

starring: Elisabeth Shue, Nicolas Cage, Julian Sands, Richard Lewis, Laurie Metcalf, Steven Weber, Emily Procter & Valeria Golino.