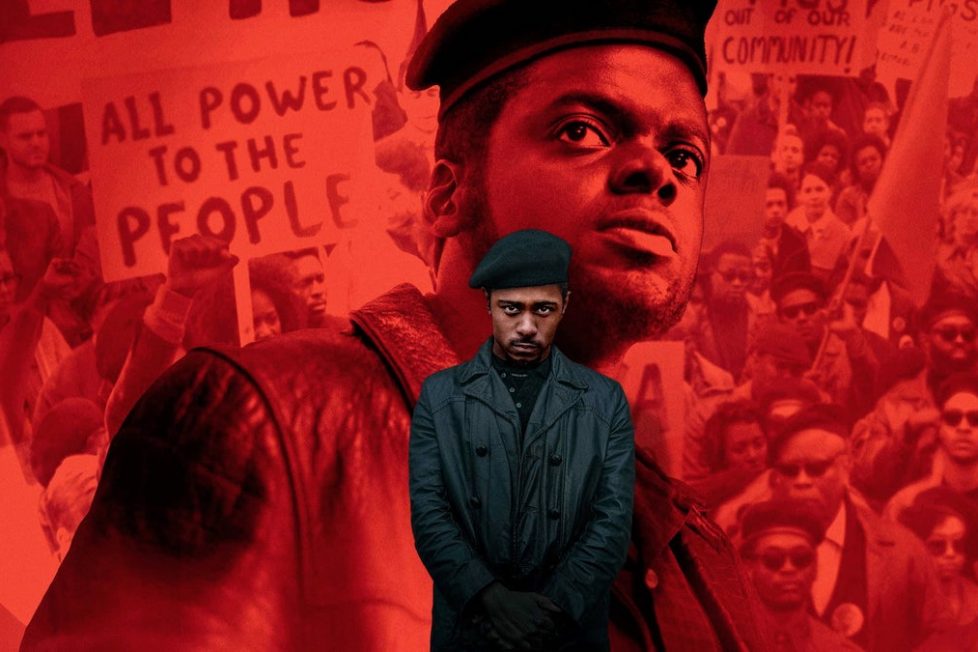

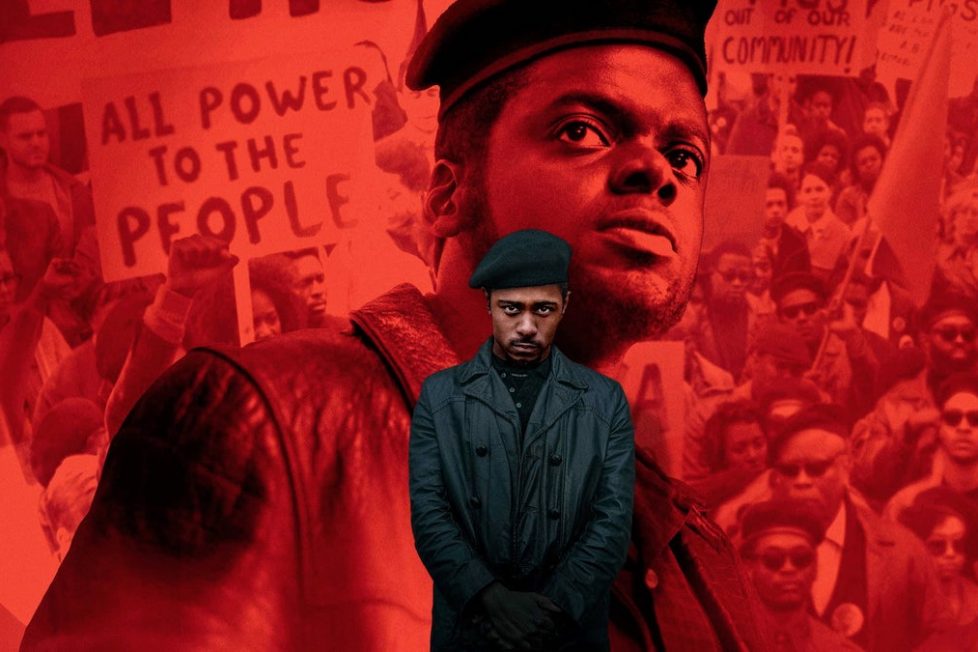

JUDAS AND THE BLACK MESSIAH (2021)

The story of Fred Hampton, Chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party, and his fateful betrayal by FBI informant William O'Neal.

The story of Fred Hampton, Chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party, and his fateful betrayal by FBI informant William O'Neal.

Then one of the twelve, called Judas Iscariot… said unto them, ‘What will ye give me, and I will deliver [Jesus] unto you?’ And they covenanted him for thirty pieces of silver.

Matthew 26:14-15

Except his name wasn’t Judas; his name was William O’Neal, arrested by the FBI in 1966 for car theft, and brought in as an informant to spy on the Black Panther Party, one of the most prominent American civil rights groups of the decade. He also wasn’t paid 30 pieces of silver; he was offered freedom from all charges for his petty crimes in exchange for information on Jesus and the Panthers.

Then again, Jesus wasn’t his name, either; his name was Fred Hampton, the charismatic Marxist-Leninist leader of the Panthers’ Illinois chapter, hailed as the next Black Messiah to lead a burgeoning civil rights revolution. And just as Jesus was killed after Judas betrayed him, Hampton, too, was killed after O’Neal informed on him—not by crucifixion, but by assassination in 1969.

It’s rare to see a film that successfully represents such an influential religious narrative through this history without taking dramatic license. In some sense, that’s because the real-life story of Fred Hampton, William O’Neal, and the latter’s infamous betrayal is itself a perfect allegory; where Shaka King’s Judas and the Black Messiah comes in, however, is how it portrays this story with galvanizing finesse and expertise, utilizing said story’s tragic, dramatic weight to the fullest possible effect.

One of the major smash-hits from last month’s 2021 Sundance Film Festival, Judas and the Black Messiah evolves past the traditional trend of unexceptional, often saccharine cinematic depictions of pivotal historical figures. Rather, it’s an emotional retelling of Hampton and O’Neal’s story to disciples who are willing to hear. A harrowing reminder of an individual’s divinely unique impact, as well as the influence of fear when it spreads down the rungs of a society built on shaky ground.

As the title implies, the film doesn’t primarily take on Hampton’s perspective, but O’Neal’s (Lakeith Stanfield), following his journey as he rises up the Panthers’ ranks and finds himself at the literal centre of conflict between the Panthers and the federal police. His story starts when he’s apprehended by the FBI and meets agent Roy Mitchell (Jesse Plemons), who, as explained above, offers to drop O’Neal’s charges for grand theft auto and impersonating an officer if he agrees to be an informant on the Black Panther Party. O’Neal, prioritizing his freedom, takes up the offer, willing to reveal whatever he can dig up.

What he soon discovers, however, is that the Panthers aren’t “violent terrorists” leaving a non-stop trail of wanton destruction and dead police wherever they go, as Mitchell describes. Instead, under the supervision of their electrifying Chairman, Fred Hampton (Daniel Kaluuya), they’re on a mission to unite several disparate, disenfranchised groups (ranging from affiliated gangs to Puerto Ricans to even impoverished rednecks) trapped by an America that refuses to help them, promising them revolution and drastic change through civil rights.

Hampton is, in equal measures, an expert orator and a salesman, delivering charismatic, deeply persuasive speeches in one moment and cleverly promoting breakfast programs on the street to passers-by in another. He’s also—as his relationship with Deborah Johnson (Dominique Fishback) reveals—introspective and romantic when the occasion calls for it, a contrast in personality that seems both surprising yet appropriate for a figure so in tune with emotionality.

As tensions intensify to the point of violence between the Panthers and the police, so does the internal conflict brewing within O’Neal—who evidently seems to take a shine to Hampton and his cause, even as he continues to inform on him to Mitchell and the FBI. It’s from this point onward that the film begins unveiling its full hand in regards to moral complexity, and the inevitable tragedy to come is only more painful to consider when what’s truly at stake becomes so incredibly clear. Through this complexity, Hampton and O’Neal are both revealed to be characters who don’t capitulate to broad, archetypal depictions of either Messiah or traitor, and that’s in part thanks to Kaluuya and Stanfield’s spellbinding performances, respectively.

Kaluuya as Fred Hampton is, with zero doubt, an invigorating presence. It’s difficult not to get utterly transfixed by his charisma and range, built up over the years with films such as Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) and Steve McQueen’s Widows (2018). In almost all of his scenes, it feels as if he’s using every possible inflexion in his voice, every action he makes with his body, to genuinely convey Hampton’s indefatigable flame for civil rights and cultural equality, and that effort pays off explosively, consistently, and cathartically. The film also does particularly well not to dilute Hampton’s radical sensibilities and ideologies, something that’s difficult to see in more accessible films such as The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020), which also happens to feature Hampton as well as his eventual assassination.

Stanfield is also an immense standout in this film, vulnerably portraying O’Neal as a man who’s conscious of the precarious dilemma he grows to face—the choice between the legal freedom that only his oppressors can give, or the risk that comes with integrating into the movement that has his best interests in mind. With every passing moment, O’Neal’s every unfortunate choice is driven by the fear that results; fear that the authorities will throw him into jail once more, and fear that the Panthers will discover him for who he really is even after he’s shown dedication to their cause. The tragic irony is that he never rises above this fear even to the very end, and Stanfield ensures that this emotional susceptibility is made clear to the audience watching his every move.

Jesse Plemons and Dominique Fishback, meanwhile, are the supporting role sleeper hits among the cast, complementing the two protagonists in their own unique ways. For Plemons, he’s gradually built a reputation for delivering numerous subtly layered, quietly deliberate character-focused roles. In that same vein, his portrayal of Roy Mitchell adds to the film’s understated dimensionality, giving us the realisation of how desperate Mitchell is to satisfy his virulently racist FBI supervisors, and how he heartlessly uses O’Neal as a means to that end.

Fishback, meanwhile, is nothing short of excellent as Deborah Johnson, who becomes the only person among the Panthers to learn of Hampton’s more private and intimate side as she slowly falls in love with him. In many ways, it’s with their blossoming romance in mind that the final moments of the film, which place a surprisingly significant emotional focus on her, only become that much more heart-rending to watch.

From a stylistic point of view, the experience of watching this film unfold is further supported by director Shaka King’s distinct visual aesthetic, emulating the atmosphere of late-1960s America down to the flashy Buicks, the simple uniforms, the neon-lit buildings, and the vivacious jazz score (brilliantly composed by Mark Isham and Craig Harris). Eagle-eyed fans of director Steve McQueen’s work may also be familiar with the look and feel of Judas‘s cinematography, and that’s no coincidence. Director of photography Sean Bobbitt, who’s worked with McQueen on every one of his feature films, with the exception of the Small Axe (2020) quintet, retains his raw and kinetic style with this film as well, using sweeping, dynamic tracking shots alongside moody colours, intense close-ups, and vivid lighting.

What Judas‘s unequivocal craftsmanship boils down to is a kaleidoscopic portrait of an America entrenched in this one-sided racial conflict—a country where white supremacist violence is law, and where every triumphant civil rights victory is sucker-punched again with every Black death at the hands of law enforcement. “Fear” is the operative word in such a society, and Judas is a film that leaves it lying around every corner, both in regards to its characters’ individual plights, as well as the tension that comes with every one of the Panthers’ successes and failures. It is a tragedy based on both a downfall that seemed crushingly, systematically inevitable, and a betrayal carved into the obscured annals of America’s racial history.

But there’s also a vestigial sense of hope here, and one need only look again at its title to discover where that hope comes from. For one, the legacy of Hampton’s sacrifice will continue on with thousands of people who fight for his cause long after his death, even if he himself may never return to life in a Second Coming. As for O’Neal, his story seems to end the same way as Judas’s—with repentance and suicide in 1990, decades after Hampton’s death. Shaka King, however, asks us to look beyond the association with unforgivable treachery that Judas’s name wields, informing us of what came both before and after the betrayal, and imploring us to use the lessons from O’Neal’s internal conflict as a reminder to fight fear whenever it emerges—especially when it matters most.

USA | 2021 | 126 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Shaka King.

writers: Will Person & Shaka King (story by Will Person, Shaka King, Kenny Lucas & Keith Lucas).

starring: Daniel Kaluuya, Lakeith Stanfield, Jesse Plemons, Dominique Fishback, Ashton Sanders, Darrell Britt-Gibson, Lil Rey Howery, Algee Smith & Martin Sheen.