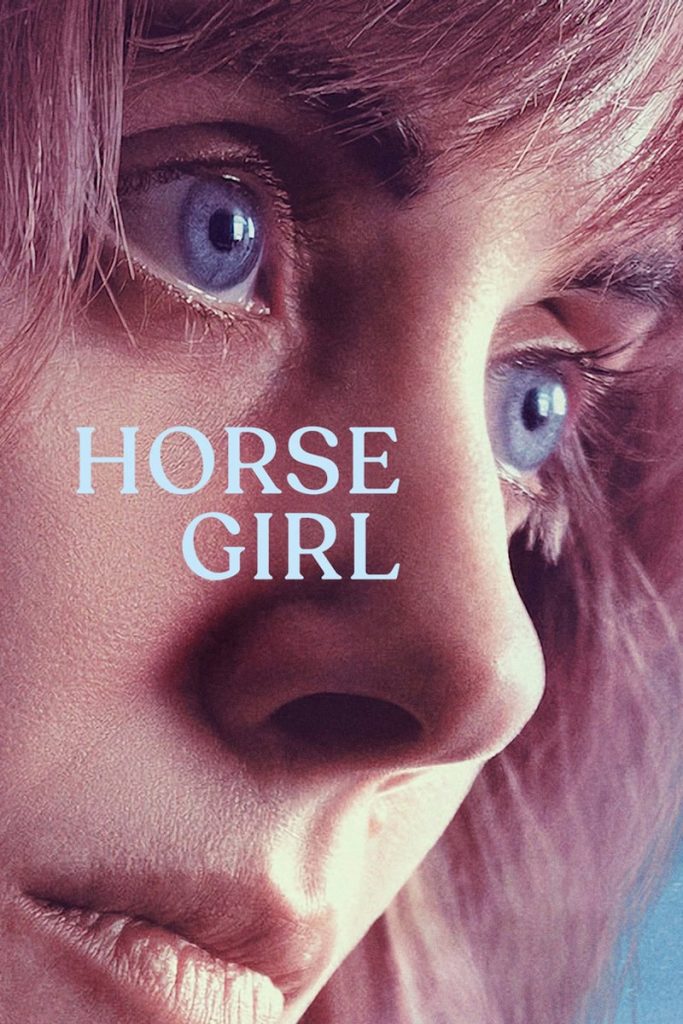

HORSE GIRL (2020)

A socially isolated woman with a fondness for arts and crafts, horses, and supernatural crime shows, finds her increasingly lucid dreams trickling into her waking life.

A socially isolated woman with a fondness for arts and crafts, horses, and supernatural crime shows, finds her increasingly lucid dreams trickling into her waking life.

Jeff Baena’s Horse Girl is one of those strange, dreamy movies that leave you wondering what you just saw and if anything made sense. As the movie progresses it becomes apparent that Horse Girl, dominated by an unshowy but magnetic Alison Brie (who co-wrote the script with Baena), is immersing us in the perspective of her character’s unstable mind. And it remains memorable long after the end credits precisely because we’re never sure exactly where “reality” ended and the odd universe of Sarah (Brie) began.

There’s a gorgeously irrational dream sequence, for example, which might not be a dream; there’s the young woman who shares Sarah’s room in a psychiatric hospital, and maybe exists but possibly doesn’t; then there’s the ambiguous ending, which could be realistic, or metaphorical, or anything in-between. It all starts mundanely enough with the kind of safe, formulaic wackiness that characterises a lot of modern US indie cinema (Horse Girl, like Baena’s previous three films, premiered at Sundance).

Sarah is young, single, lonely, but putting a brave face on it. People call her “nice” in that way that’s not quite critical but certainly not flattering. She’s employed at a craft store called Great Lengths, chatters away with co-worker Joan (a characterful Molly Shannon), and shares an apartment with the considerably more confident Nikki (Debby Ryan). They’re on good terms but aren’t exactly friends and Sarah seems to spend most of her time watching a wonderfully cheesy demon-hunting TV show called Purgatory.

So far, so quirky-by-the-numbers, and one might be preparing for a movie that’s nothing more than a study of a sensitive young woman trying to cope with a brasher world. Poignant and forgettable. You might even think, briefly, that we’re in for an agonising comedy of manners when Nikki invites her dumb boyfriend Brian (Jake Picking) around for an evening of fake bonhomie and terrible white rap along with his roommate, the gentle giant Darren (John Reynolds, in an outstanding performance).

A shy romance between Darren and Sarah struggles into being and their awkwardness is excruciating to watch while ringing so true. But there have already been hints that not everything about Horse Girl is going to live up to its indie stereotypes. The first shots (the sky seen through trees, fading to a long-held close-up of a single plain colour, unidentified until we see that it’s fabric Sarah and Joan are cutting up at the craft store) already suggested Horse Girl isn’t concerned with portraying the world as most people see it, but with the particular and immediate experiences of Sarah as she wanders through life.

And there have been faint, but unmistakable, signs that people around Sarah are cautious about her. Something seems off about Sarah’s attachment to a particular horse at a riding stable, too. Then the strangenesses mount up: she sleepwalks and there are peculiar scratches on the apartment wall when she wakes up. Later they also appear on the roof of her car. So she starts investigating phenomena like “time loss”, alien abduction, and carbon monoxide poisoning…

Most importantly, about an hour in, Horse Girl takes on more serious and sad overtones after a date with Darren turns into a disaster. Then Sarah’s far-out convictions seem to get stronger and stronger, as she becomes convinced she’s a clone of her own grandmother, so ends up styling her hair just like her long-dead relative. Sarah also comes to believe technology is controlled by a god called Satico Satellite, before imagining she can “hear the future” and sewing herself an alien-style costume.

The more troubling mood doesn’t preclude some continued comedy. There’s a hilarious scene with an ear, nose, and throat specialist (a perfectly-judged David Paymer) where Sarah’s questioning expands from nosebleeds to dreams and aliens, while the doctor does his best to remain non-judgmentally helpful–but by the end, we have little idea what’s real and what’s not. And perhaps neither does she! Moreover, this doubt spreads retroactively to the earlier parts of the film.

This is the point, of course. Brie described Horse Girl as depicting “how terrifying it is to not be able to trust your own mind.” Similarly, Sarah says “I know it sounds really crazy, but it just feels really real.” A comment which could apply aptly to the atmosphere of the film itself.

But despite Horse Girl’s weighty theme and one tear-jerking subplot about a horse, it never gets mired down by an excessively solemn or sententious tone. It’s helped in this by consistently astute performances from its ensemble–including John Ortiz as a plumber who Sarah fixates on, and Jay Duplass as a social worker who sees her in hospital. Not one of them strikes a wrong note, but not one stands out excessively, either.

Baena delivers unfussy direction. Only the occasional emphasis on apparently random objects (a plughole, a box of jewellery, that fabric at the beginning) hints this film occupies a slightly different world from most, aided by cinematographer Sean McElwee’s great eye for composition. The score by Josiah Steinbrick and Jeremy Zuckerman matches the visual style; simple and hypnotic with pizzicato and pitter-patter effects.

If the movie has a slight flaw it lies in repetition. The concept of dysfunction, of one kind or another, is delivered in the form of a homeless guy ranting incoherently about the tech-god Satico Satellite; in references to a history of mental illness in Sarah’s family; even in her friend Heather (a nice cameo performance from Meredith Hagner), who suffered brain damage in an accident but seems truly happy. It’s as if we’re being reminded, over and over again, that all sorts of people have mental health issues, that this may explain Sarah’s behaviour, and that we shouldn’t pigeonhole her because of it.

Surely we knew that already? Still, this problem is minor and barely detracts from the story’s flow. Horse Girl is slight, certainly—a portrayal of one woman in one situation, which raises questions it doesn’t even try to answer, and which certainly doesn’t attempt to convince us of anything. In that respect, it’s almost the opposite of what they used to call an “issue movie”.

Perhaps, as Alison Brie intended, it exists to give us an impression of what it’s like to be in Sarah’s situation. But only afterwards will audiences start consciously applying labels like “mental illness” and try to separate fact from fantasy. For Horse Girl’s 103-minutes we’re absorbed into Sarah’s crazy world, which is sometimes sweet, sometimes alarming, sometimes touching, and at moments just beautiful.

director: Jeff Baena.

writer: Jeff Baena & Alison Brie.

starring: Alison Brie, Debby Ryan, John Reynolds, Molly Shannon, John Ortiz & Paul Reiser.