HANNAH AND HER SISTERS (1986)

Between two Thanksgivings two years apart, Hannah's husband falls in love with her sister Lee, while her hypochondriac ex-husband rekindles his relationship with her sister Holly.

Between two Thanksgivings two years apart, Hannah's husband falls in love with her sister Lee, while her hypochondriac ex-husband rekindles his relationship with her sister Holly.

Conversations flow as freely in Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters as the jazz music that filters in and out of the film’s interlinked love affairs. One of cinema’s greatest—and most unsung—pleasures is observing characters who’ve known each other their entire lives, and the trust that blossoms from that knowledge. It turns their dialogue into a fast-paced dance, where even the prickliest arguments abound with a love born of true understanding. When these characters bitterly tear into one another, even that’s a form of love—a constant push-pull dynamic where they can practically predict their interlocutor’s responses.

The three sisters at the heart of this comedy-drama drift in and out of changing fortunes, disastrous affairs, and dependable relationships. At times, they know their loved ones better than they know themselves; at others, they’re helplessly distant. The eponymous Hannah (Mia Farrow) is the most stable of the trio, managing to be all things to all people. Whether she’s labouring in the kitchen for a dinner party, playing with her children, or thriving in her latest acting role, she rises to the occasion. Her sister, Holly (Dianne Wiest), has a far more precarious career as she bounces between drug use and new ventures. Rounding out the trio is Lee (Barbara Hershey), a “kept woman” stuck in a dreary marriage to Frederick (Max von Sydow), a cantankerous, much older artist.

Together, they understand each other completely, but once men are involved, all hell breaks loose. In Hannah and Her Sisters, the rhythm of conversation is so rapid it makes the unpredictable predictable. Chaos becomes normalcy, to the point that arguments are anticipated moments before they occur. But romance is a seismic force, disrupting everything until these sisters hardly know each other, or themselves. Internal ruminations occur far more sparingly than spirited conversation, yet the former is always more revealing. Polite talk or fiery rows are flattened into internal doubts, all stemming from a central insecurity. In the private corners of our thoughts, our perspective takes on a haphazard rhythm, oscillating between misgivings.

Allen’s screenwriting is sharper here than in almost all his other pictures. Conversations and internal digressions flow so naturally you forget there’s a story structure at all, let alone a rigid one. Inspired by Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander (1982), the film is centred on three years of family gatherings (though Christmas is swapped for Thanksgiving). Within this overarching structure are individual chapters introduced via quotes from the film or literature. The latter are steadily supplied by Hannah’s husband, Eliot (Michael Caine), to Lee; a married man desperately smitten with his wife’s sister.

It’s fascinating to watch how quickly the film’s unions are severed through voice-over monologues, where hidden allegiances, desires, and frustrations are finally voiced. At no point does this sideline any particular character, though it’s worth noting that Hannah is easily the least defined. Is that simply because she has no “problems”, so her contentment reads as vagueness compared to the neurotics around her? It’s certainly possible, especially when squaring her personality against her ex-husband, TV writer Mickey (Allen). Like almost all of Allen’s self-insert characters, Mickey’s a neurotic freak—a desperate, antsy being who looks uncomfortable in his own skin. In this case, he’s also terrified of his own mortality, constantly deluding himself into believing he has various terminal diseases.

More so than any other character, Hannah and Her Sisters is structured through Mickey’s desperate search for meaning. When worrying over non-existent medical diagnoses yields no solution, he attempts to find purpose in religion. On a first watch years ago, I was most enraptured by the film’s dramatic core: the wistful, bittersweet passion Eliot shares for Lee. But so much of that passion stems from Hannah’s undefined characterisation; you know so little about what makes her tick that you feel as if you’re viewing her through a mirror. It’s as if she were born to be a tireless worker for others. It’s impossible to see her as a victim, since that would require her to be capable of emotional depth. On the plus side, that makes it remarkably easy to side with the extramarital infatuation, despite it being an ultimate betrayal.

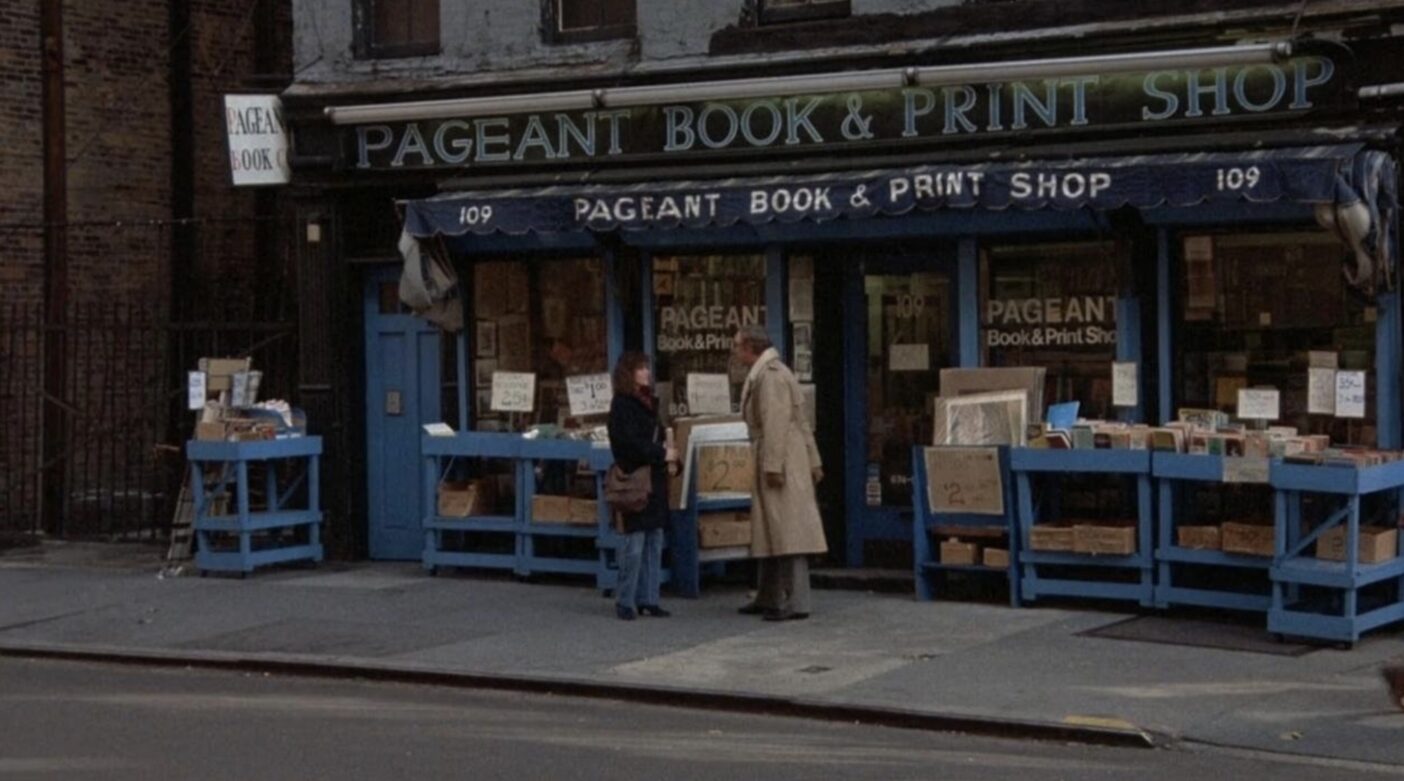

On a recent rewatch, this romance didn’t strike me as nearly as sincere as it did during that swooning first viewing. More surprising still was how the frivolous Mickey carried the film, easily providing the most entertainment. Allen is a talented actor, but he’s not a captivating leading man, arriving pre-packaged with a trademark neurotic shtick. It’s no wonder his films are usually around the 90-minute mark; not only does he excel at light comedy-dramas, it just wouldn’t be interesting to follow these anxious “sad sacks” for any longer. But as Mickey, Allen is dispersed across this narrative sparingly enough that I noticed a smile creeping up whenever he reappeared. In many ways, Mickey is the least important member of the cast, always hanging on the periphery, but where it counts, he’s the film’s structural glee.

Dianne Wiest is also marvellous as the fretful Holly, who can never quite find the right niche. As she drifts through different career paths and down familiar, unwise avenues, it’s a delight to witness her struggle towards success. She’s far more volatile than Mickey, engaging in playful arguments that sing their own tune. Do these characters even realise that the way they express conflict is beautiful? They know each other fully, so it’s probably better they never find out: they’re beautiful because they lack self-consciousness. Of course, their conversations are their own kind of performance, as the anxious monologues cleverly reveal.

The trouble with a film of this kind is that it’s dominated by trouble, so someone like Hannah appears to lack characterisation just because she isn’t wracked with worry or shame. There’s no way for the film not to do her a disservice, especially as she’s the only named character in the title, implying dramatic heft. Despite the name-drop, this is a thankless role. Mia Farrow excels anyway, appearing simultaneously as the most pragmatic, intelligent character and the most naive. She isn’t ignorant, but innocent—and there’s no place for that in Allen’s world of schemers and doubters.

On a recent rewatch, Eliot’s love felt far more fickle, carried only by the poetry he recommends to Lee (like E. E Cummings’ incomparably sweet “somewhere I have never travelled, gladly beyond”). Mickey’s bickering and neurotic musings on whether life has a purpose prove far more entertaining. Unlike the director’s ravishing journey into the past in Midnight in Paris (2011), Allen’s finest qualities shine here when he tries to make the audience laugh instead of wooing them with charm. But there’s still one essential quality bound to make one swoon: the conversations in Hannah and Her Sisters are music to one’s ears. They possess a melody whose tempo is remarkably easy to fall in love with.

USA | 1986 | 107 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Woody Allen.

starring: Mia Farrow, Barbara Hershey, Dianne Wiest, Michael Caine, Woody Allen, Max Von Sydow, Maureen O’Sullivan, Julie Kavner & Lewis Black.