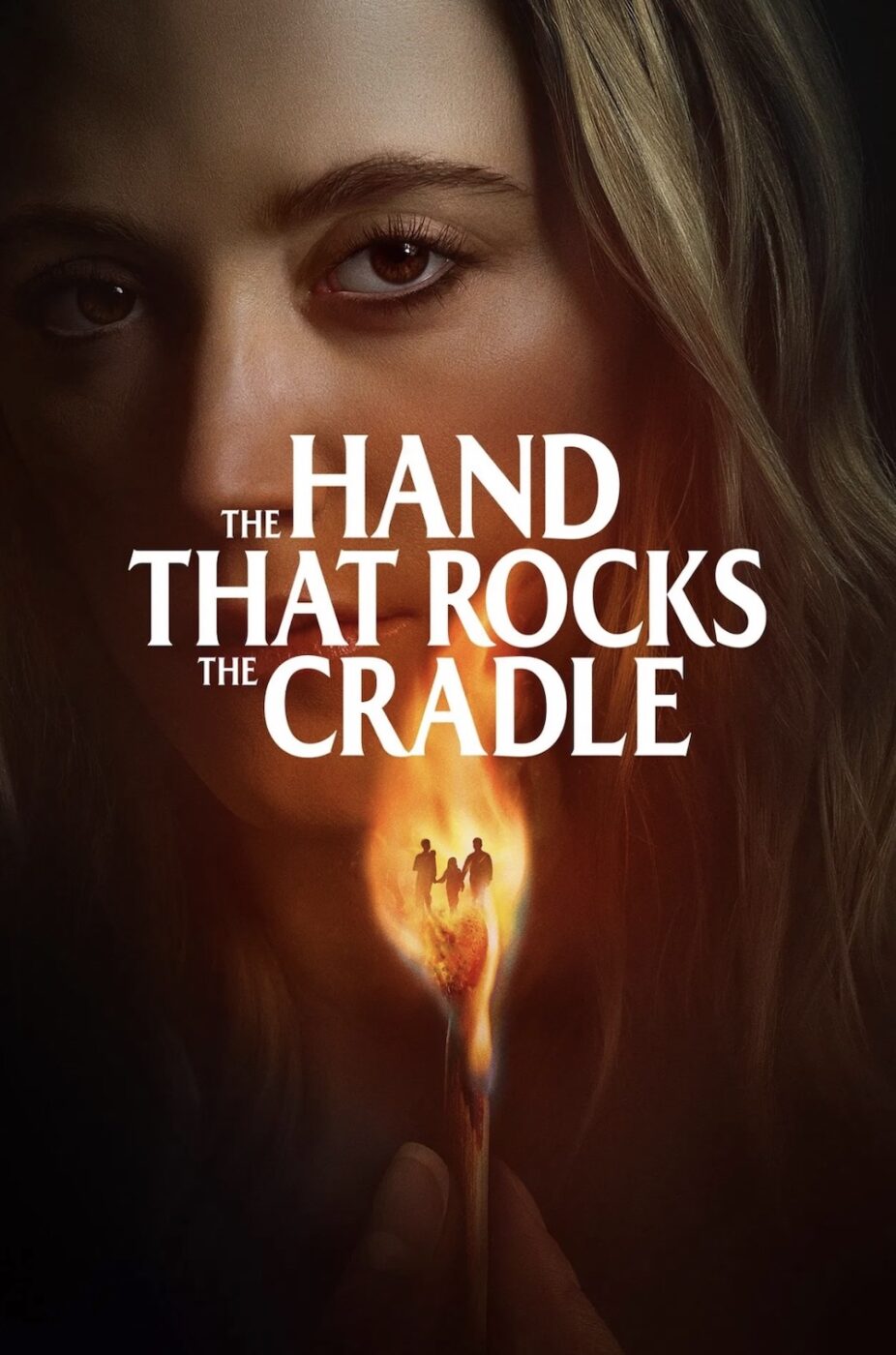

THE HAND THAT ROCKS THE CRADLE (2025)

An upscale suburban mom brings a new nanny into her home, only to discover she's not the person she claims to be...

An upscale suburban mom brings a new nanny into her home, only to discover she's not the person she claims to be...

There’s something irresistible about a revenge plot in a domestic setting, especially if it involves two women, murder or sabotage. Though far from new to the medium of film—Single White Female (1992), Hush (1998), Fatal Attraction (1987) and Disclosure (1994) had kept us entertained throughout the 1980s and 1990s—it’s certainly nostalgic and lively as ever, when properly executed. Since the release of A Simple Favour (2018), there’s been no shortage of similar tales, or maybe they just faded out of fashion. This doesn’t accurately explain why The Hand That Rocks The Cradle needed a reboot, but here we find ourselves.

Screenwriter Micah Bloomberg and director Michelle Garza Cervera reimagine Amanda Silver’s original screenplay, changing much to the confusion of many viewers still loyal to the 1992 version. The 2025 film remains within the genre, though this is credited to the lead actresses overall. Caitlin Morales (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) is a suburban mother who hires a nanny to help her juggle her career and family life, while beneath her composed exterior lies a woman desperate to maintain control over a life slipping away because of a recent miscarriage. Her counterpart, Polly Murphy (Maika Monroe), a familiar face in the horror and thriller genres. Polly comes to Caitlin’s aid working as a nanny, seeking to infiltrate her employer’s life and enact revenge on her for a prior grievance. Right away, we’re in good hands with these two.

Both Monroe and Winstead have built their careers playing strong, complex women, and their experience shows throughout the film. Winstead’s best portrayal is arguably her role as Michelle in 10 Cloverfield Lane (2016), a kidnapped survivor in a post-apocalyptic America. Meanwhile, Monroe’s made strong performances as characters who are unsettling and emotionally troubled, such as Ruth in the sci-fi Significant Other (2022).

In these films, neither’s a victim and this stays relatively true for their roles in The Hand That Rocks The Cradle. It’s actually one of the better payoffs promised by the film. By the end, the line between hero and victim is ambiguous, but what we do know is that both are complicit in their own ways. Winstead and Monroe’s display of outward emotion is truly the driving force and emotional current of the film. Caitlin is more reactionary (we could say disturbed and understandably angered) at Polly’s clear strategy to dismantle her life through sabotage and threat. Polly, in contrast, is restrained and withdrawn. Monroe’s droopy, bright brown eyes and quiet unease hint at layers of unresolved trauma ready to be peeled back. Together, the tension between them is just about the best thing about the film.

The film’s other strength lies in its visual style. Belgian cinematographer Jo Willems—whose credits include Hard Candy (2005), The Hunger Games trilogy (2008-2010), 30 Days of Night (2007), Finch (2021), and The Long Walk (2025)—brings The Hand That Rocks the Cradle more to life. This isn’t a surprise. His work in 30 Days of Night is a masterclass in cinematography, balancing visceral gore and action with cold colour palettes to emphasise the terror of the isolated, Alaskan setting when murderous vampires overrun the town.

Here, Willems uses mostly interior shots of Caitlin’s sunlit and candlelit suburban house and juxtaposes them with the shadowy, run-down motel that at one point Polly inhabits before she agrees to be a live-in nanny. This visual duality, though short-lived, reinforces the divide between Caitlin and Polly’s worlds—quiet privilege versus noisy misfortune—and how they cope with their shared guilt. A dinner scene with Caitlin’s best friend Stewart (Martin Starr) illustrates this contrast quite well: Stewart’s smug, ignorant remarks about Polly’s living situation highlight her precariousness, emphasising the social gulf between the classes. The way this scene is written, acted and shot, is one of the more useful methods of creating confluence when embedding social messages along with Polly’s motives for her actions. Others, however, aren’t.

What most viewers are likely to take umbrage with is the film’s attempt to be nearly unrecognisable compared to the original, mainly by inserting social messages and simultaneously trying to stay along the lines of a revenge plot. Although an admirable feat for any filmmaker, it’s also a challenge that few can excel at in the modern age. You can’t please everyone even when you try to scramble up a decent omelette. There are very few films better than their original, itself a debate worthy of an academic-length essay.

The original film, which starred Rebecca De Mornay, took its title and idea from an 1865 poem by William Ross Wallace. The Hand That Rocks The Cradle (1992) sought to spin the trope of the mother figure—described in Wallace’s poem more or less the female role of nurturer as critical to the development of humanity, demanding praise—on its head and it did so successfully. The Curtis Hanson and Amanda Silver film isn’t just a cult classic today but it did, during its time, earn more than $140M at the box office on a $11M budget at a time when domestic thrillers were becoming more mainstream. You could say it’s one of those films that paved the way for A Simple Favour and even Promising Young Woman (2020)—the latter somehow executed a good balance of dark comedy with commentary on gender dynamics and injustice packaged inside a revenge thriller.

The new film, however, downplays the original’s messages about motherhood, instead embedding themes about modernity, possibly causing viewers to question their relevance to the overall plot. Caitlin’s sexuality, for instance, is repeatedly brought into focus, namely when her past romantic experiences are revealed by Polly to Caitlin’s family. While Polly’s actions clearly aim to destabilise Caitlin’s marriage, they may fall flat because the family downplays these revelations. Whereas the original film had the husband figure Michael Bartel (Matt McCoy) a more active role, here Miguel Morales (Raúl Castillo) is almost redundant, as Polly’s own sexuality undermines any attempt at a shock-worthy seduction. This, however, could be the point. More broadly, the film may suggest that modern society is indifferent to behaviours once viewed in the past as provocative and sinful. Emotional detachment can reflect a cultural tendency to forfeit accountability or concern for others’ actions and beliefs, particularly regarding sexuality.

On one hand, this intensifies Polly’s anger towards Caitlin, deepening her revenge plot. On the other, it can flatten viewer expectations, as its modern commentary feels trite and disrupts the main storyline. By the climax and reveal, however, the film’s central question emerges: can people forget about the past and forgive those who have wronged them?

The original film succeeded in this regard because it conveyed its themes subtly, letting them unfold organically and giving the story a sense of depth and satisfaction almost akin to a mini-series. Some reboots have even surpassed their originals—The Mummy (1999), War of the Worlds (2005), and 3:10 to Yuma (2007) come to mind—but these benefited from decades of refinement, top-tier directors, writers and actors to achieve what might otherwise have been impossible.

This isn’t to downplay Micah Bloomberg and Michelle Garza Cervera’s efforts, as the film is watchable and attempts to bring something new, but it highlights the need for a bridge between the old and the new, one that complements rather than erases. A modern example of successfully complementing an original story is Season 2 of Castle Rock (2018–19), which was adapted from Stephen King’s separate fictional worlds, placing them together in a series sandbox.

In that series, Lizzy Caplan’s portrayal of a young Annie Wilkes from Misery added layers to Annie’s psychosis and motives, a prelude to her becoming the infamous villain, detached from real life, as portrayed by Kathy Bates in the earlier 1990 film, without erasing her character. Conversely, remakes like The Hand That Rocks The Cradle face limitations as films whereas a series format may have allowed the story to explore more layers and nuances without expunging the kernels of the original, giving audiences a richer experience.

US | 2025 | 105 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Michelle Garza Cervera.

writers: Micah Bloomberg (based on the screenplay by Amanda Silver).

starring: Maika Monroe, Mary Elizabeth Winstead, Raúl Castillo, Martin Starr & Mileiah Vega.