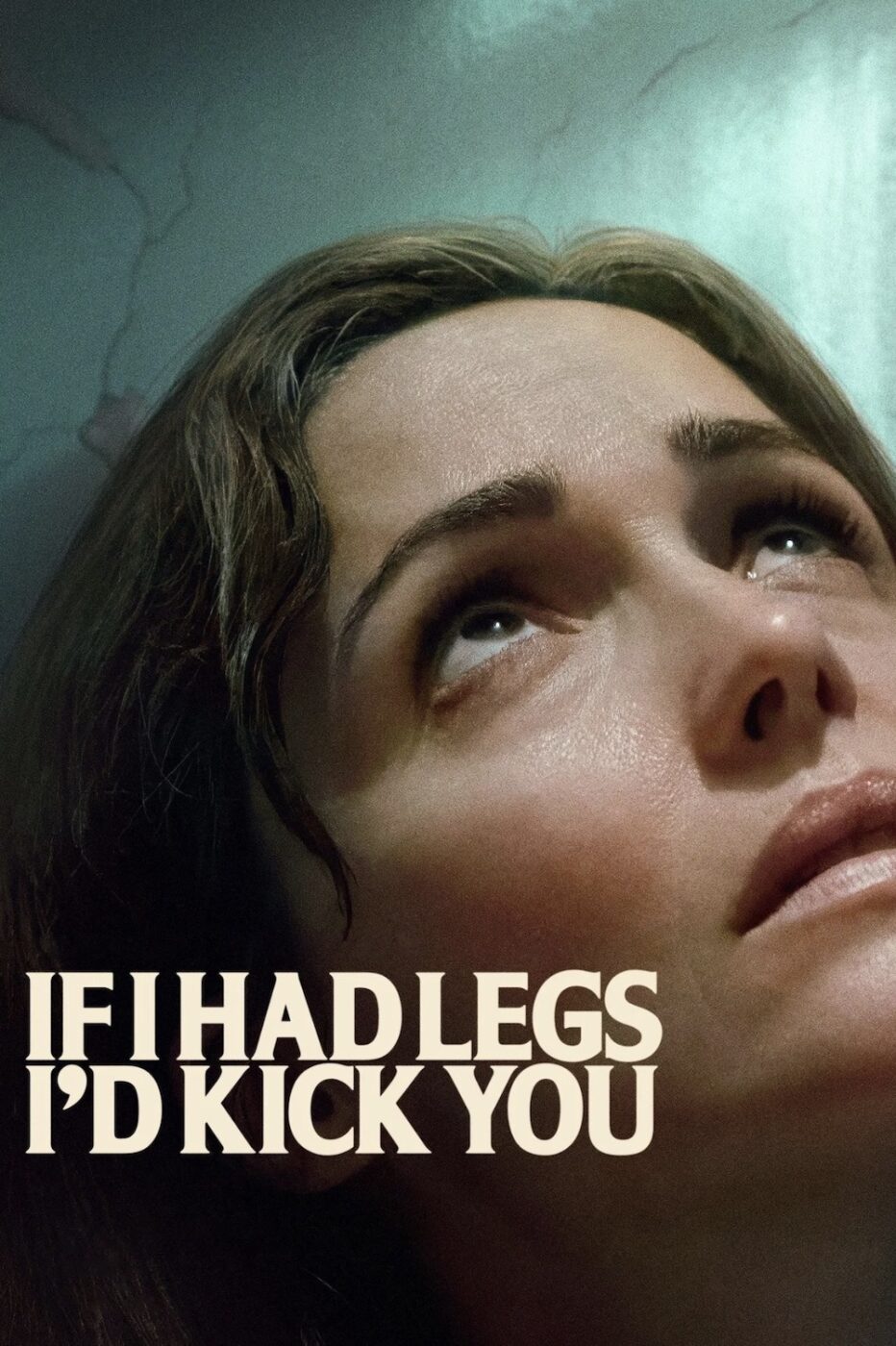

IF I HAD LEGS I’D KICK YOU (2025)

With her life crashing down around her, Linda attempts to navigate her child's mysterious illness, her absent husband, a missing person, and an increasingly hostile relationship with her therapist.

With her life crashing down around her, Linda attempts to navigate her child's mysterious illness, her absent husband, a missing person, and an increasingly hostile relationship with her therapist.

I was an incredibly unhealthy baby. I’ve often heard my parents’ anecdotes about how hard it was for them to contend with my illnesses after bringing me into this world. I don’t have a firm grip on the details; I was too young to remember any of it. But I don’t think I ever truly understood how my parents’ recollections of my infancy all had one common detail: they cried throughout all of the hardest episodes. They aren’t frequently emotional people, and yet they were terrified my condition would be chronic or untreatable without taking drastic measures. It was a grim stretch of my infancy, and my lack of memory doesn’t help me understand the weight of that—nor the miracle it is that I’m now in a relatively healthy condition.

If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, from writer-director Mary Bronstein (Yeast), is so relentless in its portrayal of the worst two months of a mother’s life that it finally allowed me to experience the terror my parents must have felt. There’s no other way for me to frame how visceral the experience of watching this film is, how tense and punishing nearly every second of it is, how it finds the way to raise the stakes with each passing scene. Its air of panicking dread is so all-encompassing that it elicits laughter out of raw discomfort, that it takes even minor crises in its protagonist’s life and proceeds to equate them with her worst disasters. It’s a formally exciting movie on nearly every level. Rose Byrne’s performance is also a once-in-a-lifetime endeavour. It’s also a film I’ll have trouble revisiting anytime soon. It unflinchingly and aggressively renders a world driven by self-interest and apathy, yet still has the courage and clarity to realise what it is we still need to depend on.

When Linda’s (Rose Byrne) framed in extreme close-up, in a single long take shot (the first of the film), one already gets a sense of exactly what it is she’s struggling with, and how badly she’s already coping with it. Raising a precocious 10-year-old daughter (Delaney Quinn) is a hard enough affair. Raising one afflicted with a mysterious stomach ailment that prevents her from eating, that requires her to have a tube surgically inserted into her intestines, is a whole other level of challenging.

One of Bronstein’s many means of submerging us in Linda’s point of view, is visually obscuring her daughter in almost every scene she’s in. As a result, the presence Linda’s daughter has as merely a voice amplifies the extent to which Linda fails to see her daughter beyond the issues she has and feels obliged to solve. Her daughter’s voice nags at Linda, a disembodied force, trapped inside her subjectivity, and barely a human presence to begin with.

Linda’s daughter isn’t the only person in her life contained to just to a voice. Her husband (Christian Slater), away piloting a cruise for the next two months, is also confined to Linda’s phone calls, growing increasingly dismissive as Linda’s venting is met with “what about the work I’m doing?!” deflections, reeking of pure disregard for the responsibilities offloaded to Linda in his absence. To make matters worse, when an appointment regarding Linda’s daughter’s condition ends, and the two of them walk back inside their place… the ceiling of their bedroom completely caves in on itself, sending a torrent of water through with a force so overwhelming I was convinced the speakers were being blown out right then and there.

Soon after, cinematographer Christopher Messina’s camera slowly crawls up into the hole left behind to create one of the most menacing opening credits sequences of recent memory. It’s a chilling, near-hellish effect, where the hole becomes a gateway to a void containing a maelstrom of Linda’s worst experiences and most terrifying memories. Thus begins If I Had Legs I’d Kick You’s central firestorm of chaos, compiling inconvenience, and overwhelming distress—a tone that persists continuously for the entire film and never once lets up for even a minute.

As Linda’s world begins to spiral outwards, the cast of characters surrounding her begins to grow at a steady pace. Many of them offer up some kind of levity; all of them prove to be some kind of thorn in Linda’s side. Linda herself works as a therapist, but gets therapy sessions down the hall from one of her fellow therapists—played by none other than former chat show host Conan O’Brien, in a surprisingly convincing turn. O’Brien suppresses his amicable charm and delivers a quietly hostile and apathetic performance that allows him to bring a darker breed of humour to the fore, as he carelessly wings his way through giving Linda support.

And when Linda’s forced to move with her daughter into a motel until the hole gets fixed, one of the front desk attendants there, James—played with laissez-faire energy by A$AP Rocky—proves to be one of the movie’s most magnetic sources of lighter charm. He’s vastly more interested in casually sharing recreational drugs off-market with Linda to spend time with a new neighbour than letting her spiral off a tour of binge-drinking on her own every single night.

Life is forced to continue on for Linda, even after the catastrophe of her daughter’s illness is met by the catastrophe of the hole in her ceiling. And yet, even as life goes on, every encounter she makes soon devolves into a nightmare. One of Linda’s clients, Caroline (Danielle Macdonald), is a new mom rapidly spiralling into paranoia, unreasonably concerned about the health risks her new child faces, and the threat of a dangerous world surrounding both of them. With each passing session, her fears grow more and more uncontrollable, steadily leaking into how Linda grows to perceive her own daughter… before Caroline’s sudden disappearance in the middle of a session kicks off yet another wild train of events in the nightmare carousel of Linda’s life.

As things like this start to build up further, even small inconveniences begin to prove garish in their own right. Linda’s daughter’s overzealous desire to get a hamster leads to one of the most cleverly gruesome usages of practical effects in recent memory. The other front desk worker at the motel, Diana (Ivy Wolk), becomes increasingly stringent about the exact times in the night that Linda’s allowed to purchase drinks. A parking attendant (Mark Stolzenberg) harasses Linda with increasing frequency for spending too long in the lot while dropping off her daughter at the care centre.

The list continues on. And inevitably, the gradual pivot towards Linda’s breaking point grows increasingly difficult to witness. She begins to equate catastrophe and inconvenience as the result of what seems to be a grand cosmic joke, and her subjectivity grows increasingly unstable, harrowingly reflected by the recurring appearances of the void from the film’s opening credits.

Its soundscapes, already empty and frigid in their construction, steadily become unbearably hostile, housing the agonising screams that haunt Linda’s worst traumas, and the noise that overtakes all of her senses. Even the sights the void contains are surprisingly convincing portrayals of memories. Emerging from it are barely distinguishable scenes, in which the impression of what’s going on is their focus, and in which the actual events of those memories leave a greater impact from their emotional brutality than their more tactile details. The knowledge that all of the void’s special effects are also practical only makes this visceral presentation that much more impressive.

Rose Byrne (Ezra) is powerfully effective at portraying Linda in this harrowing stretch of her life, a role that would challenge most actors in convincingly portraying someone hanging onto the absolute end of their rope. In the hands of a less skilled performer, Linda would have felt overbearing, hard to connect with, and overdone to the point of bathos. But Byrne toes the perfect line with Linda from beginning to end. It’s a performance committed to showing the morbidly hilarious ends to which Linda will go to scramble back up her rope, before unravelling in such violent fashion that it becomes difficult not to identify with how she resorts to frenzied measures. Accentuated by continuous close-up shots, the physical minutiae of Byrne’s performance are left completely bare and unfettered, and she controls all of them exceptionally.

Slowly, Linda’s avenues for help begin to dissipate. Her therapist grows sick of her; her doctor (played by Bronstein herself) threatens to cut off support for her daughter. She begins to hurt the people who want to get to know her better and who depend on her, the sting of her carelessness deepening with each blow. And when it all culminates in one of the most emotionally brutalising final stretches of any film in recent memory—kicked off by a sickening act of raw desperation that nauseatingly snaps into focus the consequences of Linda’s unravelling—the film’s final shot and formal gesture is so gracefully incorporated that it brings a shocking level of clarity to all of its terror and noise.

With If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, Bronstein isn’t playing coy about the disastrous consequences of our individualistic culture, where our need to only look after ourselves comes at the expense of those who need our support. Nearly all the sources of Linda’s greatest sources of pain stem from the fact that no one is equipped to help her in any way she needs, and that the people who should be helping her instead reject every opportunity to do so.

It’s also a frightening portrayal of motherhood on the edge not seen since the likes of John Cassavetes (A Woman Under the Influence) and Darren Aronofsky (Requiem for a Dream). Here, apathy can become something extremely dangerous, where it can threaten to destabilise how mothers choose to see their children, and where it comes with deeply sown regrets our culture has deemed taboo to verbalise. But the final few seconds of the film are also an acknowledgement of a remarkably simple way through the noise, only made difficult to find by the fact that our institutions have deliberately made it so. It makes this deeply astonishing film a howlingly earnest, desperate plea for empathy that its terrifying sound and fury only amplifies a hundredfold.

USA | 2025 | 113 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Mary Bronstein

starring: Rose Byrne, Delaney Quinn, Conan O’Brien, A$AP Rocky, Mary Bronstein & Ivy Wolk.