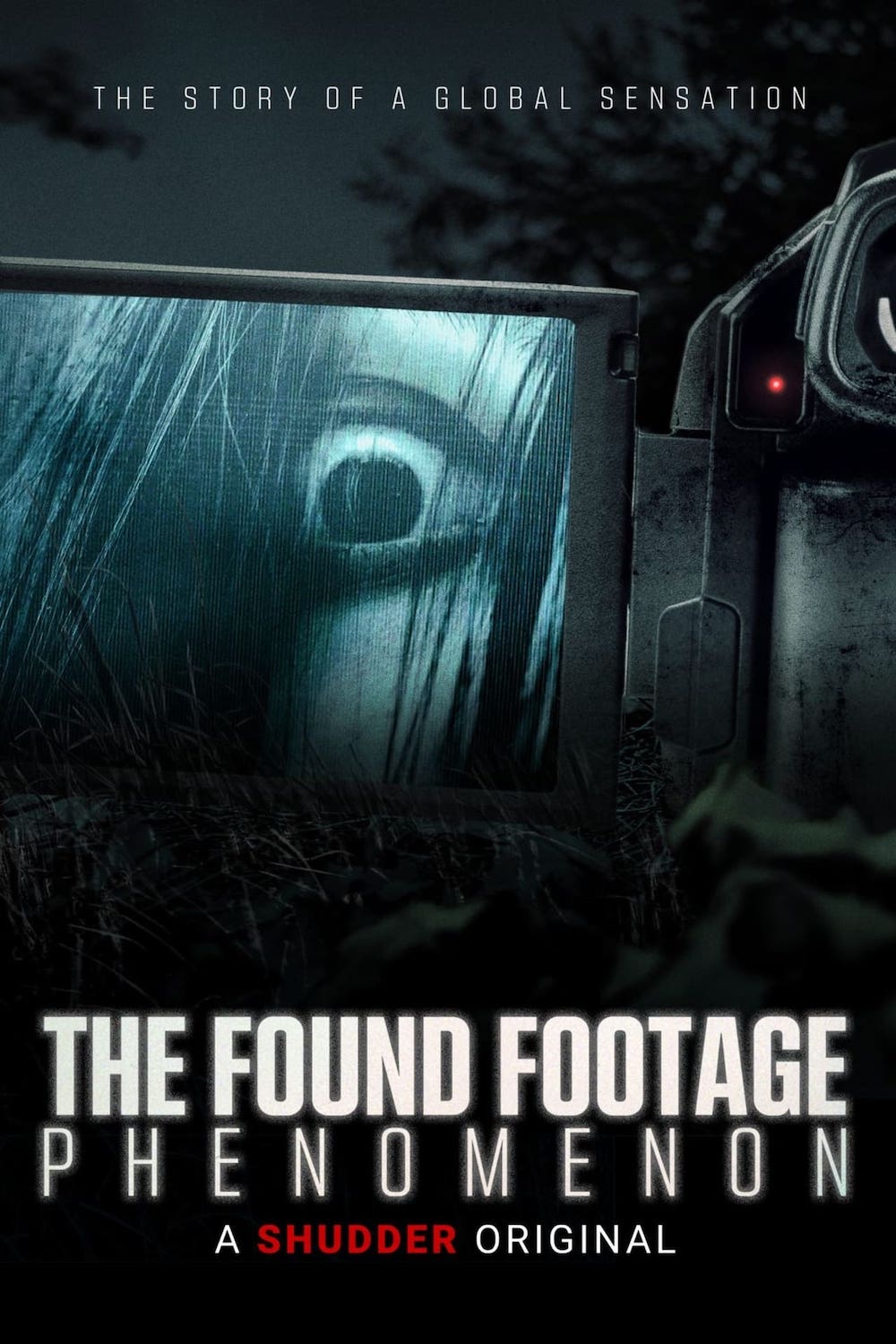

THE FOUND FOOTAGE PHENOMENON (2021)

A documentary tracing the origins and development of found footage movies.

A documentary tracing the origins and development of found footage movies.

The British Library catalogue lists 766 titles for “film noir”, 377 for “Stanley Kubrick”, 143 for “Citizen Kane”… and 140 for “found footage”. The filmmaking style that burst into public awareness with The Blair Witch Project (1999), after several decades in the shadows, has since gone mainstream and become the subject of intense academic study as well as a familiar experience for filmgoers.

There’s a danger its familiarity could prove to be its own undoing, or at least diminishment, as the effectiveness of good footage movies come from the way their immersive, subjective positioning of the viewer in a messy, low-quality quasi-reality differs from the tidier, more objective conventions of most commercial films. Even an unconscious recognition that it’s just another filmmaking technique must detract a little, as did the larger budgets that were applied to some projects after the huge box-office success of found footage’s two touchstone films, Blair Witch and Paranormal Activity (2007).

But what is it exactly? A precise definition is surprisingly difficult to pin down. As some of the discussion in Sarah Appleton and Phillip Escott’s new documentary The Found Footage Phenomenon illustrates, there are those who prefer narrow classifications (one interviewee, for example, suggests that not only must the footage be created by characters, but they must also be missing), as well as those arguing for much broader ones.

Found footage didn’t just appear from nowhere, as many of the principles underlying its approach derive from cinéma vérité and the Dogme 95 movement, for example. And there have always been films including supposedly real, but actually staged, footage—the newsreel in Citizen Kane (1941) itself is an example, while Movie Movie (1978) consists entirely of two allegedly old, in fact brand-new, films. Then (as Cecilia Sayad points out in an excellent Cinema Journal article on the topic) there are films such as Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) which can be seen as hoaxes of a kind, claiming to be based on real incidents while not overtly pretending that their actual images are real.

The key point, perhaps, is that in true found footage films the movie (or at least part of it) is made within the context of the narrative (the film academic Zachary Ingle calls this the use of a “diegetic camera”). The audience sees the movie-makers or at least is made aware of their existence within the world of the film; the proposition of authenticity is total, and all the paraphernalia of filmmaking becomes a guarantor of authenticity, not a source of artifice.

Where most movies strive to conceal the act of filmmaking, these foreground it—for example, by allowing characters to look straight at the camera, as Peter Turner notes in his book on Blair Witch), and their premise almost always leads to a particular visual style: handheld cameras, often jerky movement, natural lighting, naturalistic dialogue. We tend to overlook the fact that even within their own reality they must be edited.

Even among found footage movies, though, there’s a distinction that needs to be drawn between those like Paranormal and Blair Witch where the audience is supposed to believe (or at least pretend to believe) in the genuineness of the footage, and others like Cloverfield (2008) or Trollhunter (2010) where that level of suspension of disbelief is not really being called for.

And then there are mockumentaries like What We Do in the Shadows (2019), which seems to fit the bill but is rarely counted as found footage (though, as pointed out in this documentary, the 1992 Man Bites Dog bridges the gap). There’s also a completely different meaning for the term “found footage” to indicate collage in art films, and it is sometimes used in a documentary context too.

The concept isn’t unique to film, as it has firm literary origins, with novels like Horace Walpole’s 1764 The Castle of Otranto or Bram Stoker’s 1897 Dracula telling their stories through what might be termed “found texts.” While The Castle of Otranto is purportedly a translation of a 16th-century manuscript, Dracula (more famous than the Walpole as an antecedent of found footage movies) is told entirely through letters, diaries and other documents, many of them claimed to be by the novel’s characters, and sets out what might almost be a philosophy of the pure found footage movie: “All the records chosen are exactly contemporary, given from the standpoints and within the range of knowledge of those who made them.”

Later, one of the most famous examples of the approach comes from radio: Orson Welles’s 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast. But what does seem to be consistent in the many manifestations of the found footage concept is that it is most successfully, or at least most often, applied to horror. Although (as Neil McRobert has observed in an article for the journal Gothic Studies) it has been used for other genres such as SF (Chronicle), comedy (Project X) and the police procedural (End of Watch), “these films are exceptions that prove the rule”.

Possibly, the inherently unsettling nature of uncertainty, the absence of full knowledge, explains why found footage is so suited to horror. And, just like low production values, ambiguity and even an absence of explanation can become a confirmation of realism. (It’s interesting that one of the biggest criticisms levelled at Blair Witch, by those who disliked the film, is the seemingly undramatic nature of its allusive climactic shot; would that be more acceptable, and more easily understood, for an audience today with two decades’ experience of watching such movies?)

It may have been Blair Witch and Paranormal Activity that propelled found footage to the forefront, aided—as various commentators, including some on this disc, have suggested—by factors as diverse as the immediacy of the way 9/11 unfolded on-screen, the popularity of reality TV, and the need for revival in a rather stagnant horror genre. But (even disregarding Walpole in the 18th-century) found footage has its roots much earlier. The deep dive into its history is one of the strongest aspects of Appleton and Escott’s documentary.

There’s no agreement on a single first example, perhaps inevitably given the fuzzy edges of the style’s definition, and not all of the early found footage films are horror. Wikipedia, for example, suggests The Connection (1961); one interviewee here mentions the opening scene of Michael Powell’s notorious Peeping Tom (1960), where the murderer himself is filming one of his crimes. Later that same decade there’s David Holzman’s Diary (1967), far removed from the grimmer topics with which the technique became associated although not without its sinister side; in a more lurid territory, the Italian mondo films of the 1960s with their dubious claims to documentary status can also be at least partially classified as found footage.

Cannibal Holocaust (1980) is recognised as a landmark, even if it’s clearly not the first, as often stated. Films employing the style continued to trickle out during the 1980s and 1990s, most of them obscure–The McPherson Tape (1989) is one of those discussed here, for example, and even the now relatively well-known The Last Broadcast (1998) was barely noticed on first release—before the Blair Witch-inspired explosion at the beginning of the new century.

After that, it wasn’t long before name directors got in on the craze (for example George A. Romero with 2007’s Diary of the Dead and Brian De Palma with Redacted the same year); popular genres like torture porn also have some affinity with the found footage approach, though in that particular case it’s the extreme explicitness of the realism rather than found footage’s frequent obliquity which makes it powerful.

Meanwhile, low-budget independent films continued to be produced; found footage spread internationally with movies such as Rec (2007) from Spain and Shirome (2010) from Japan; and in the 2010s the increasing dominance of screens in everyday life made possible a new style of found footage movie based not on ostensibly filmed material but on the content displayed by computers and phones. For example, Megan is Missing (2011) and, more famously, Unfriended (2014).

Inevitably, the style also went meta with Found Footage 3D (2016) depicting the misadventures of a group of filmmakers set out to make a fake found footage movie. The creepy potential of found footage also surely lies behind some movies and TV dealing with filmed records in a broader sense—for example, Netflix’s Archive 81 (2022) and Prano Bailey-Bond’s film Censor (2021).

Many of these points are discussed in Appleton and Escott’s consistently interesting documentary, which takes an essentially chronological approach and features an impressive line-up of names from found footage’s early days as well as the present, ranging from Ruggero Deodato (Cannibal Holocaust), Stephen Volk (1992’s Ghostwatch) and Eduardo Sánchez (Blair Witch) to Andre Ovredal (Trollhunter) and Kōji Shiraishi (Noroi: The Curse from 2005).

The choice of films is excellent and goes far beyond the obvious, throwing up many candidates for the watchlist. Interviews are largely in English and rarely too repetitive, although like many documentaries The Found Footage Phenomenon does take a while to get going (why devote so much time to telling us the subject is worthwhile when we’ve already committed to watching anyway?) and, again like many documentaries, would benefit from more regular on-screen identification of speakers and films.

“We live in a world that is found footage” thanks to smartphones, one of the interviewees observes—and to that, of course, one could add YouTube, surveillance video, and so forth. It’s no surprise the style seems to speak particularly well to our times, and perhaps the disturbing feeling of watching events that are uncontrolled also resonates with contemporary viewers.

True, it doesn’t have quite the impact it could’ve had 20 years ago, precisely because we’ve now seen so much of it, but entering the mainstream hasn’t robbed it of its immediacy and potency. The found footage style still has much to give and, especially for those who’ve seen a few examples and would like to explore a little more, this documentary is a fine overview.

UK | 2021 | 101 MINUTES | 16:9 | COLOUR • BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

writers & directors: Sarah Appleton & Phillip Escott.