FIVE EASY PIECES (1970)

A dropout from upper-class America picks up work along the way on oil rigs when his life isn't spent in a squalid succession of bars, motels, and other points of interest.

A dropout from upper-class America picks up work along the way on oil rigs when his life isn't spent in a squalid succession of bars, motels, and other points of interest.

In one of the key scenes of Bob Rafelson’s Five Easy Pieces, classical pianist turned oil-field roustabout Robert Dupea (Jack Nicholson), making a half-willing return to the family home after a long absence, plays a piece of Chopin for his brother’s fiancée Catherine (Susan Anspach). She, a musician like the family, praises his performance… but he disparages it, saying he could play the piece better when he was a child. “Can’t you understand it was the feeling I was affected by?” she asks. “I didn’t have any,” replies Robert.

A superficial take on Five Easy Pieces might see that line as summarising the entire film: Robert has no feelings and that’s why he treats his girlfriend Rayette (Karen Black) so badly. It’s also why he’s given up the piano, given up on his family, and seemingly given up caring about anything.

But that would be simplistic. For Robert is, in fact, driven by feeling: he’s always searching for something that will satisfy him and never finding it. He claims to be happy-go-lucky, criticising Catherine for wanting everything to be “grim and serious”, but in truth his life seems to be a series of short-term jobs and relationships he flees once things get difficult. He’s left his middle-class, high-cultured origins for a hand-to-mouth, blue-collar existence in a town typified by the pawn shop and porn cinema we see him walking by, only to find he is not at home there either.

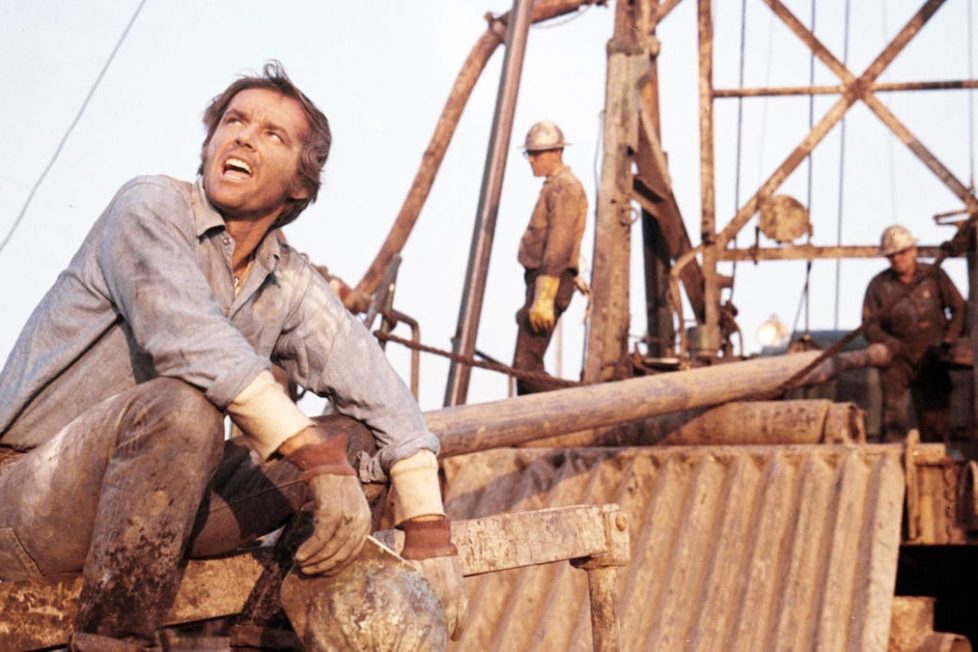

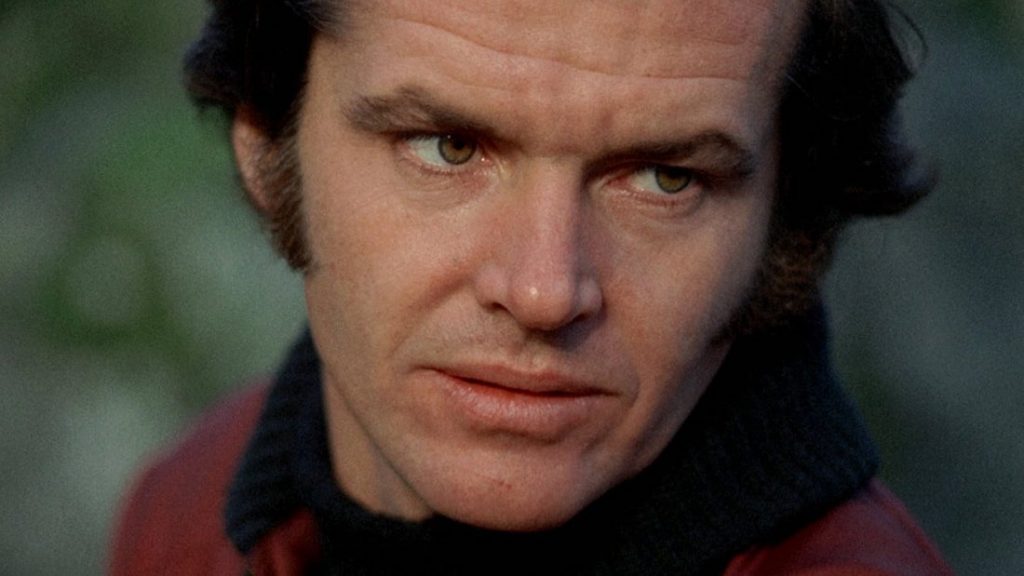

Nicholson’s Robert is the embodiment of disaffection and alienation, clearly representing a certain kind of American in the late-1960s (and perhaps even the country itself), discontented with conformism but finding traditional means of rebellion equally empty. Film critic Pauline Kael called the character “the familiar American man who feels he has to keep running because the only good is momentum.”

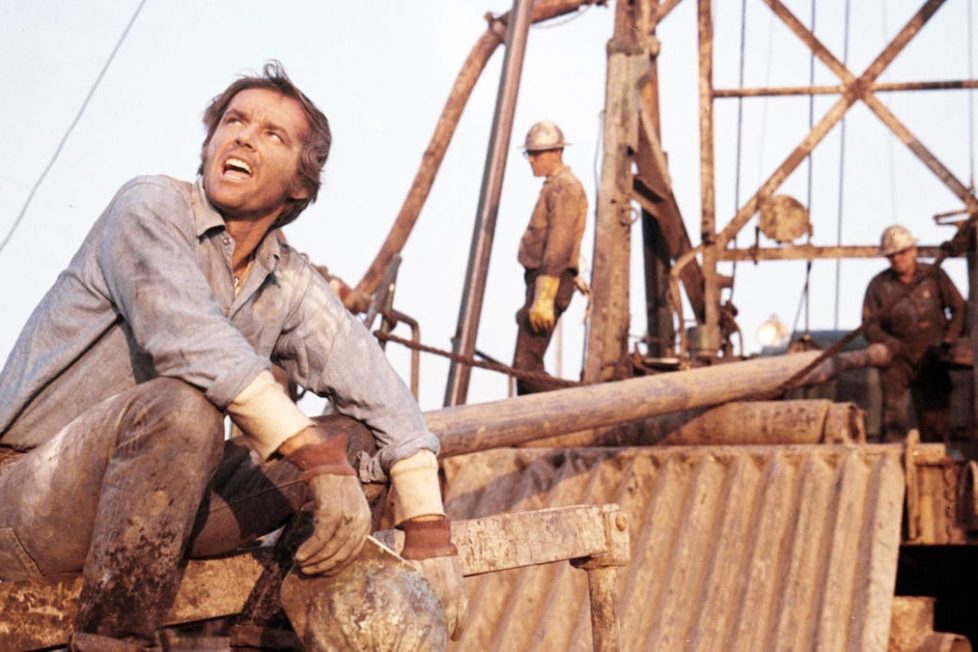

Like many films of the New Hollywood era which it helped kickstart, Five Easy Pieces is a conspicuous departure from what film historian David Thomson (in one of the extras on this Criterion Blu-ray) describes as the “serene fantasy” of earlier American cinema. It begins on an oil-field near Bakersfield, California, where we see Robert doing tough, physical work with his pal Elton (Billy Green Bush). They go bowling, they cheat on their women, and Elton is arrested for skipping bail, but not before revealing to Robert that Rayette is pregnant. Robert is clearly not interested in fatherhood, and seems to be intending to leave her, but he won’t come out and say it.

Instead, in what must have been a surprising scene for audiences of the time when it was released, we suddenly meet a much more smartly-dressed and polite Robert driving to Los Angeles and visiting a recording studio, where he’s greeted affectionately by a classical pianist who turns out to be his sister, Tita.

The pretentiousness of the Dupea family that Robert’s tried to escape is slyly encapsulated in their names: his second forename is Eroica, after a Beethoven symphony; Tita stands for “partita”; his brother Carl’s second name is Fidelio after the Beethoven opera. Yet there’s an obvious connection, a genuine emotional intimacy, between Robert and Tita that’s missing from his relationships with Rayette and Elton. Family, it seems, isn’t so easily discarded after all.

And when she mentions that their father’s been sick and urges Robert to visit him, off he goes again—heading to the Pacific Northwest states (though the scenes at the family home were filmed in western Canada), reluctantly collecting Rayette on the way and taking him with her.

The remainder of the film explores Robert’s relationships with the family members ensconced at his father’s big house in the woods: Tita again, his father himself, brother Carl, and Carl’s fiancée Catherine. Rayette meets them, too, presenting screenwriter Carole Eastman and director Bob Rafelson with nice opportunities for demonstrating the gulf between the classes. Though the Dupeas don’t mean to be nasty, they can’t help being condescending toward this big-haired waitress; their lives are filled with reverence for the great composers of the past, she wishes she could sing like Tammy Wynette.

Five Easy Pieces ends inconclusively, the only certainty being that when Robert insists to a truck driver giving him a lift that “I’m fine… I’m fine… I’m fine…”, it’s more a self-delusion than resolution. He seems no less unsure of his place in life, and no more able to settle himself into any kind of happiness, than he did at the beginning. Indeed, Dupea’s inability to figure out what he really wants is highlighted through the film by a series of dualities (the dry desert versus the damp Northwest, country versus Beethoven, the intellectual philosophising of a dinner guest at his family’s home versus the crackpot philosophising of a hitchhiker he picks up) and also by some of its best-known scenes.

In one, while he’s driving with Elton, they’re stuck behind a truck carrying a piano. Robert jumps out of the car and onto the truck, then starts to play the piano. It’s terribly out-of-tune, but he either doesn’t notice or doesn’t care; nor does he notice that the truck’s turning off the road, taking him away from his car and Elton. Is he lost in music? Or just doing something dumb and fun? Or both? With this character, it’s never easy to be sure. (Car journeys and traffic jams occur many times in Five Easy Pieces, too, with self-evident symbolism—never-ending motion interspersed with frustration. “Why don’t we all line up like a goddam bunch of ants!” yells Robert during one hold-up, and it’s probably not a positive sign that the film actually ends with him at the front of a traffic jam, in the vehicle that’s created it.)

And then, in the most famous episode of the film (though one which director Rafelson points out in the extras here is irrelevant to the broader story), Robert finds himself thwarted trying to get what he wants in a diner. His desire is simple—an omelette with tomatoes and toast—but that exact combination isn’t on the menu and the waitress rigidly refuses to allow substitutions. Robert tries to game the system by combining bits from other dishes, but she won’t have it, and once more he explodes in anger.

Again, the superficial meaning is clear—an arbitrary rule keeps Robert from happiness—but what’s equally interesting is that he seems to take as much pleasure in trying to outwit the waitress as he actually would in the omelette. Here, Robert’s character gives us hints of the cheeky, cunning guy whom Nicholson would play in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) five years later; but Robert is unhappier, more self-doubting, and while he may be deriving some satisfaction from challenging social expectations, he ultimately doesn’t get any lunch. That’s Five Easy Pieces in miniature.

This complexity in Robert means that Nicholson is effectively playing two or even three roles at once: the oil-field worker, the dutiful pianist-son, and the “real” man who lies somewhere in-between. (It’s never entirely clear to us, and it may not be to Robert, which is the most genuine.) He does it terrifically, persuading us to root for him despite his many unattractive traits—he’s arrogant toward Elton, calling him a “cracker asshole”, and cruel to Rayette in the kind of casually contemptuous way that Clint Eastwood treats Jessica Walter in Play Misty for Me (1971).

Unsurprisingly the film was a major factor in making Nicholson a movie star, but although he’s constantly present, other actors aren’t diminished by his presence. Foremost among them is Black as Rayette, easily the most sympathetic character in the ensemble; straightforward and unpretentious, frank in her need for love, but stronger than others realise.

In a consistently memorable cast, the other highlight is Ralph Waite as Robert’s brother Carl, as different from his sibling as he could be, but in his own way equally intriguing with his fussy, over-bright manner. Is he very confident, or not confident at all and trying to hide it? Certainly, the way the neck brace, about which he’s made such a big deal, suddenly disappears when the attractive Rayette arrives on the scene (and the fact he can suddenly turn his head to face her, despite having made a drama about his injury preventing it) suggests that he, too, is sometimes playing a role.

William Challee is extraordinarily impactful as the family’s father; a stroke’s left him unable to speak so he has no dialogue at all, but his expressionless face is full of meaning, and the sight of him alone with a confessional Robert toward the end is one of the film’s most striking images.

Among the women it may be Anspach, as Carl’s betrothed Catherine, who’s the most interesting. As with Robert and Carl, there’s the impression that Catherine is playing a role, initially saying that she doesn’t find Robert’s coarse manners sufficiently “charming” but slowly revealing her less uptight self. Lois Smith, meanwhile, is convincing and well-rounded as the apparently more straightforward Tita.

In smaller parts Richard Stahl stands out as a weary sound engineer working with Tita, while Helena Kallianiotes is hilarious as one of a pair of eccentric lesbian hitchhikers given a ride by Robert and Rayette, obsessed by the “filth” and “crap” of consumerist society. Perhaps few people in Five Easy Pieces except Rayette are really happy with the world, but where Robert deals with it by restlessly searching for something better or at least distraction, and his family deal with it by shutting themselves away to play music on an island (Robert calls their house a “rest home, asylum”), this woman is frankly angry.

With its focus on character rather than event, Five Easy Pieces is very much an actor’s and writer’s film, but Rafelson’s direction and the cinematography by László Kovács (who worked on the transfer for this Criterion disc) also add much. Their use of deep focus depicts Robert as a small and helpless man adrift, while shooting interiors in real locations with frequent camera movement gives them a slice-of-life ambience.

It’s not a warm movie. In part because there’s so little joy, in part because so many of the people in it are frankly annoying. Indeed the grating laughs of both Elroy in the oil-field and Carl at the Dupea family home are another example of the pairings that Five Easy Pieces so often makes, in this case hinting that wherever Robert may go, the same irritations and disappointments of life will find him.

But it is an acutely human film about the quiet tragedy of an ambivalent man in an uncertain time, brought home powerfully by flawlessly realised characters and ceaselessly imaginative writing. The movie itself, the screenplay, and the performances by Nicholson and Black were all nominated for Academy Awards, though nobody won.

USA | 98 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

Criterion’s transfer is first-rate. Rafelson favoured flatter colours, and framing is generally fairly tight, so it’s not the kind of movie where you expect a jaw-dropping experience, but both visually and aurally the disc has the quality of late-1960s/early-1970s film seen in a cinema—which is exactly what’s needed. The extras (more on which below) add plenty, not least a firm assertion by Rafelson that the title of the movie refers merely to the music that Robert plays to Catherine, and not to the number of women he beds—as often claimed, though, you need a vivid imagination to make them total five, anyway.

director: Bob Rafelson.

writer: Adrien Joyce (story by Bob Rafelson & Adrien Joyce).

starring: Jack Nicholson, Karen Black, Susan Anspach, Lois Smith, Ralph Waite, Billy ‘Green’ Bush, Irene Dailey, Toni Basil & Helen Kallianiotes.