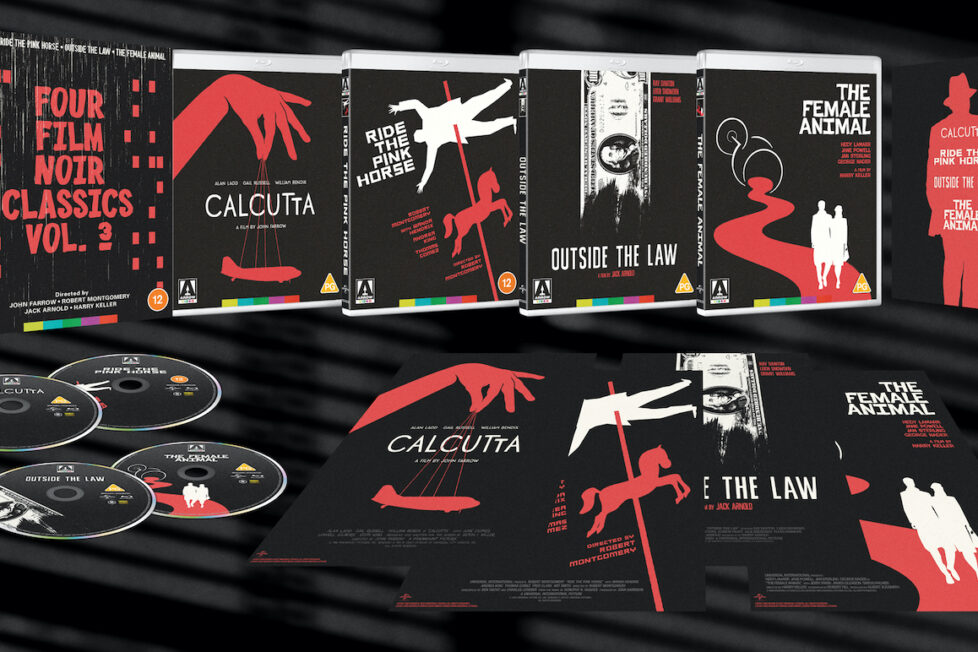

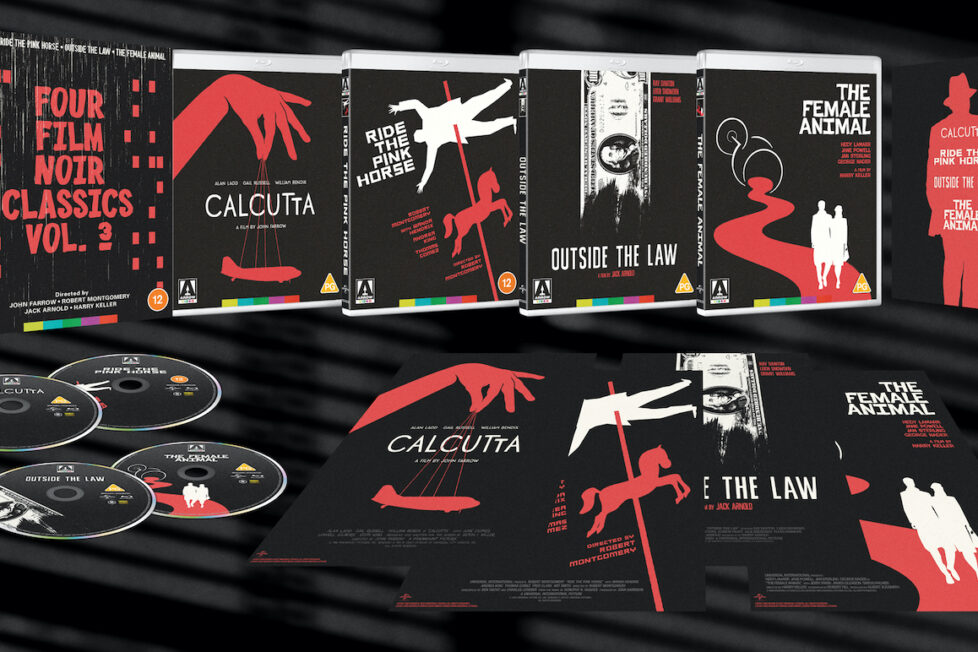

Four Film Noir Classics Vol. 3 (1946-1958)

Jealousy, greed, revenge and deceit once again run wild in another anthology of 1940s and 1950s noir...

Jealousy, greed, revenge and deceit once again run wild in another anthology of 1940s and 1950s noir...

Covering much the same era as the first and second sets in Arrow Video’s film noir series, this one again interprets the term liberally. Though there are characteristic noir elements in all four films—deception, temptation, men returned from war, women threatening their masculinity—not one of them is a moody, shadowy study of rain-slicked city streets. Two (Calcutta and Outside the Law) are more akin to conventional detective stories; one (The Female Animal) comes close to the melodramatic territory of Douglas Sirk (though not his style); and the other (Ride the Pink Horse) is set in small-town New Mexico.

As with the last set, where Robert Siodmak’s The Suspect (1944) was the clear highlight, here Robert Montgomery’s Ride the Pink Horse stands head and shoulders above the others. It’s also the most obviously noir, although still unusual in many ways, and the only one of the four to receive any critical attention nowadays.

That the other three are mostly forgotten is, to be frank, largely deserved. Outside the Law is a workmanlike enough movie but there isn’t much to make it stand out among hundreds of other competent, uninspired pictures from the period. Calcutta is both rather silly and a little bizarre, and notable mostly for Alan Ladd in the lead; while The Female Animal appeals largely on the basis of its cast rather than narrative or atmosphere.

Still, Ride the Pink Horse is such a fine, unusual and undeservedly little-known film that it alone could make the set worthwhile (and it doesn’t seem to be otherwise available on disc for the UK and Europe). The less appealing movies in the set are lifted by the Special Features, almost all of them very good.

Two American pilots in India investigate the murder of a colleague…

Calcutta was shot in 1945 but only released in the UK at the end of 1946, and not until 1947 in the US; thus it’s sometimes referred to as a 1947 film. This gap between production and release explains what seems like an odd failure to mention Indian independence, which occurred in 1947, and it also obscures a feature of the premise which might have been apparent to viewers at the time, but isn’t now.

Calcutta is supposed to be set during World War II and portray the US pilots who flew from India to China, “over the Hump” (the Himalayas), at a time when the Chinese were America’s allies in the war against Japan. But the context of the war is barely mentioned here, and indeed it only uses India as an exotic locale for a fairly mundane tale of an amateur sleuth exposing a criminal gang.

It’s certainly not a movie you’d turn to for an accurate portrayal of the 1940s subcontinent. Despite Paramount’s attempts to recruit Indian extras, the film’s city of Calcutta seems to be largely populated by Chinese and Americans; the actor Paul Singh, who served as a technical advisor and is the only person with a recognisably Indian name in the credits, reputedly knew nothing of the country. Needless to add, none of it was shot there.

Calcutta begins at Dinjan airfield in Assam, quickly introducing the US freight pilots who are its protagonists. Scenes of their flight across the Naga Hills, where they encouter mechanical trouble, and in their cockpit are all quite exciting, but are soon abandoned for Calcutta itself, a studio back-lot set done up in generic hot-Asian-country style.

Three of the flyers—Neale Gordon (Alan Ladd), Pedro Blake (William Bendix) and Bill Cunningham (John Whitney)—drink together in a bar, where Cunningham announces he’s soon to marry. Before long, however, he’s murdered with a “thuggee noose” and the other two are asked by their superior to investigate.

In the course of their investigation they encounter numerous locals who hew closely to wily-Oriental stereotypes, as well as some European women who the men seem more afraid of—particularly Ladd’s Neale, resolute in his desire to avoid entanglement. Among them are Marina (June Duprez), a nightclub performer who sings in French but is accompanied by sari-clad dancers despite the complete absence of anything else Indian in her performance. Here and elsewhere in Calcutta, one very much gets the impression of a movie trying to be something like Casablanca (1942) but with little idea of how to pull it off.

There is some interesting work by cinematographer John F. Seitz and a decent score by Victor Young, a frequent Academy Award nominee. The latter doesn’t do anything radical but musical details are often handled quite originally, with unexpected harmonies and moods. There are some strong performances, too, including those from Duprez, from Gail Russell as a contrasting girl-next-door type, from Lowell Gilmore as an obvious baddie, and from the technical advisor Singh. Edith King is memorable as a wildly OTT middle-aged lady with a pet monkey and a strong will, and an uncredited Milton Parsons is quietly scene-stealing as a hotel clerk.

Ladd, already a high-profile leading man, has as much presence as always. But there is only the faintest hint of a darker side to his personality, when he suggests to Singh’s character that they share the spoils of crime and we’re not sure whether it’s a serious offer or not; mostly, he comes across more as stubborn than as interestingly complex.

Like the rest of Calcutta, he is difficult to really care about, and that’s the central problem with the film. Despite the screenplay coming from Seton Miller, an Oscar-winner with several major films to his name (who also produced this one), Calcutta takes quite a while to even start drawing you in, and never manages to completely shake off a rather dull and lifeless feel. It will appeal mostly to Ladd fans, and aficionados of terrible Hollywood portrayals of Asia.

USA | 1946 | 83 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

A stranger arrives in a small New Mexico town, seeking revenge for the killing of his friend…

Calcutta may feel in parts like a wannabe Casablanca but it concludes with a distinct echo of The Maltese Falcon (1941), and it’s the ending of Ride the Pink Horse that most reminds one more of the famous Humphrey Bogart/Claude Rains scene at the close of Casablanca.

That’s as far as the similarities go, though. If Calcutta is an insipid schedule-filling exercise, Ride the Pink Horse is at least a minor classic.

Robert Montgomery both stars and directs here, making Ride the Pink Horse shortly after his official directorial debut The Lady in the Lake (1947), and he has a strong story to work with—Dorothy B. Hughes’s novel was also adapted for radio and then twice for TV. The great screenwriter Ben Hecht came to the project with a strong background in skullduggery (1927’s Underworld, 1932’s Scarface, Alfred Hitchock’s Notorious in 1946…) and along with his frequent collaborator Charles Lederer stays true to the essential thrust of Hughes’s novel, although some plot details were changed.

At first we might think we’re watching a western, not a noir, judging from the desert scene and the flavour of the score by Frank Skinner (who, incidentally, also composed for The Suspect on the last of these Arrow compilations). But then we see a Greyhound bus passing through the desert, and it arrives in the little town of San Pablo, New Mexico. Off steps Lucky Gagin (Montgomery), and in a highly impressive three-minute single shot he enters the bus station, sits down, takes a gun from his bag, and puts a piece of paper in a locker. There’s great tension here even in his purchase of a five-cent stick of chewing gum.

His actions seem inexplicable and this sense of mystery is heightened by the close attention of cinematographer Russell Metty’s camera to Montgomery’s every move. Later, the mood of mysteriousness spreads, and there is a pervasive sense that the town of San Pablo conceals something important and perhaps dark that Gagin himself doesn’t know about.

On a literal level the plot is relatively straightforward: Gagin is in town to blackmail Hugo (Fred Clark), a criminal boss who was recently responsible for the death of Gagin’s friend. But Gagin didn’t realise he was arriving at the same time as the annual fiesta. As a result, he can’t get a room at the kind of hotel where relatively wealthy visitors from the north like him would normally stay (parts of the movie were shot at the real La Fonda hotel in Santa Fe). Instead, he ends up being taken under the wing of two locals—Pancho (Thomas Gomez, Oscar-nominated for the role), the operator of the merry-go-round ride which gives the film its title, and the teenage girl Pila (Wanda Hendrix).

Meanwhile, the federal agent Retz (Art Smith) is also in town and hoping to arrest Hugo. So Gagin—who, it becomes clear, is no great shakes as a blackmailer and may not have thought his plan through very well—finds himself both an ally and rival of Retz.

More importantly, despite his initial dismissiveness toward the Hispanic and Indian locals, Gagin starts to grow close to Pancho and Pila. It was this aspect of Ride the Pink Horse that led James Agee to call it “practically revolutionary” in its positive portrayal of Mexicans and Indians, and the film gradually peels away the clichés to reveal the humanity beneath.

For example, Pancho starts off as a stereotype Mexican, even sleeping with his hat on his face; eventually, though, he emerges as wiser than Gagin. Pila’s presentation of a lucky charm to Gagin might at first seem like Hollywood yet again painting non-whites as superstitious, but in fact her very presence in his life is a real lucky charm: it is through her and Pancho that Gagin finally discovers his own human warmth. (The close though non-romantic friendship that the movie shows developing between an adult man and a 14-year-old girl might raise eyebrows these days, but the film clearly intends it to be interpreted innocently.)

Montgomery plays Gagin superbly: a not particularly likeable character, an uncomfortable fish out of water (wearing a coat and tie at the parade preceding the fiesta), a man who distrusts women. “I’m nobody’s friend,” he says, and he leaves us unsure for a long time whether we should see him as hero or villain. Ultimately he is neither, but he does become an object of audience sympathy (if not exactly empathy) with the help of the terrific Gomez and Hendrix.

The latter, playing a girl a few years younger than her real age, reflects Gagin’s own alienation back at him with her impassive expression, but if she seems difficult to read that’s probably because Gagin finds it hard to know what to make of someone so different from him. It was Hendrix’s big break in Hollywood though her career didn’t progress much further.

Smith also gives a strong, characterful performance as the federal agent, as does Clark as the crime lord, his huge hearing aid suggesting vulnerability that his ruthlessness and acuity contradict. (At times he might benefit from a white pussycat to stroke.) Andrea King is effective, too, as his girlfriend, a hard woman with desperation beneath and “a dead fish where her heart ought to be.”

There are many individually striking and well-staged scenes and moments in Ride the Pink Horse, such as a passage in the Tres Violetas bar where Gagin incurs the bartender’s anger by trying to pay with a bill that’s too big; the solution is to buy drinks all round, the self-styled tough guy easily taken advantage of by the locals. Much briefer, but equally powerful, is a single shot of Pila seen from behind, pulling a shawl over her head: unaccountably sinister (there is a vague air of psychological horror throughout) and capturing in one image the way that her culture is so inaccessible to Gagin.

It’s this blend of noir with culture clash that makes Ride the Pink Horse so unusual and impactful, encapsulated in the two signs over the bus station’s entrance: Buenos Dias/Howdy.

And there are other ways in which it differs very much from the supposed noir template too; the adult females are far less important than the girl Pila, for example. But in spirit it is thoroughly noir, and unlike some of the other movies in this compilation it keeps the audience guessing to the very end. If it feels a tiny bit slow at a few points, that does also help to intensify the sense that Gagin has fallen into a different world, one where the rules he’s used to don’t apply, and the many qualities of Montgomery’s film more than justify its runtime.

USA | 1947 | 101 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

An ex-convict goes undercover to break up a counterfeiting ring…

Jack Arnold—a filmmaker previously responsible for a string of still-remembered films including It Came from Outer Space (1953), Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), and Tarantula (1955)—switched genres for Outside the Law, but even so it is the least noir of the four films presented here. (It’s also completely unconnected with the 1920 Tod Browning film of the same name recently reissued by Eureka’s ‘Masters of Cinema’ imprint, which I reviewed a while back.)

The premise revolves around crime (the genuine counterfeiting problem of the period), and the milieu is law enforcement, but the real subject which the film aspires to examine is family. It begins in occupied Berlin in 1946 (an obvious sound stage), where a man is shot, but almost immediately returns to the US with its protagonist Johnny Salvo (Ray Danton), a decorated soldier and (we soon learn) an ex-convict on parole from San Quentin. His crime, hitting an old lady while drunk driving, hardly seems victimless yet in the context of the 1950s was presumably perceived by the filmmakers as forgivable enough, because there is no real attempt to present Salvo as having any dark side.

The story proper gets underway when Salvo, who had been in jail with the man murdered in Berlin, is offered a pardon in return for going undercover and penetrating a counterfeiting gang with which the dead man had been involved. Conveniently, Salvo’s father (Onslow Stevens) is the investigator in charge of the case; equally conveniently and predictably, Salvo’s work on it involves seeing a lot of the dead man’s glamorous widow (Leigh Snowden).

The criminal scheme is quite complicated, and Outside the Law even abandons Salvo for a while in its efforts at explication; this isn’t much of a problem, however, because Danton is so flat in the lead role, seemingly limited to just a couple of facial expressions. A rather routine movie thus gets a little more interesting when it turns away from the leading man to explore the criminal gang. It’s clearly Salvo’s relationship with his estranged father that the movie wants us to focus on, but although it has intriguing aspects it’s undeveloped, and a decent performance from Stevens is not enough to offset Danton’s dullness.

Other creditable performances come from Snowden as the widow, with plenty of personality; Jack Kruschen, a characterful cop; Grant Williams as a cold, psycho gangster; and Maurice Doner in a tiny but touching role as an immigrant who discovers his money is fake. The musical score, apparently assembled from pre-existing material, is very over-excitable—more than is warranted by the rather plodding movie. There are some ideas with potential in Outside the Law, and some good performances, but it doesn’t make enough use of them to rise above mediocrity.

USA | 1956 | 81 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

A movie star and her daughter become rivals in love…

No fewer than three women—Hedy Lamarr, Jane Powell and Jan Sterling—are billed above the male lead (George Nader) in The Female Animal, and all of them want to possess him. But not all of them are femmes fatales by any means. Indeed, the most unexpected thing about Harry Keller’s movie is that Lamarr’s Vanessa Windsor, an ageing Hollywood star who hires film extra Chris Farley (Nader) as a caretaker after he saves her life in an accident on-set and then takes him as a lover, is not shown as an extravagantly monstrous figure like Gloria Swanson’s character in Sunset Boulevard (1953) or Bette Davis’s in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962).

Instead, Lamarr plays the character straight and she is written more as a tragic heroine than a gorgon; Vanessa does genuinely love the younger man, and does genuinely learn from her own disappointments. Unfortunately, her adopted daughter Penny (Powell) is also in love with him, while the embittered ex-child-star Lily (Sterling) is at least in lust with him, and is played in Swanson/Davis style.

The Female Animal takes its characters seriously, then, and doesn’t always go where you might expect with them. But it doesn’t quite succeed in persuading us to take them entirely seriously, the ending is a little weak (again, because the movie likes its characters too much), and there are implausible aspects: why doesn’t Vanessa’s daughter recognise her mother’s beach house, for instance?

Lamarr and Nader, only seven years apart in age, don’t convince as a generation-gap couple; nor does Vanessa really seem old enough to be Penny’s mother. Given all this, it is an unintentional irony that this movie, where the idea of Lamarr as a fading actress past her prime isn’t quite plausible, was in fact her last one (something which also gives resonance to the discussion of acting in the final scene).

Nader gives a convincing performance as Chris, less ambiguous than many noir protagonists but still a proud and independent man whose manhood is challenged by a dominant female—a characteristic concept for the genre, and one visible in both Calcutta and Ride the Pink Horse too. The standout in the cast, though, is Powell as Lamarr’s daughter, who brings whole scenes alive with her energy (especially in her first encounter with Nader’s Chris, where she starts off drunk in a bar and ends up being shoved into the shower by him). Hans J. Salter contributes an effective score with good orchestration, and there are some interesting LA locations.

There is some quite smart self-referential humour, too—Lamarr telling a young boy that TV is a “naughty word”, an exploitation filmmaker played by Jerry Paris planning a movie about a man-eating orchid, a pair of star-struck old ladies, a meta joke about dream sequences.

The Female Animal was released on a double bill with Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil (1958), with which it shared a producer in Albert Zugsmith (and which is also shortly to be reissued by Eureka). These days, of course, that film enjoys a classic status which The Female Animal falls far short of. Still, even if it doesn’t quite have the bite you might hope for, it’s a well-acted variation on some common noir ideas.

USA | 1958 | 84 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

The transfers of all four films are excellent, particularly in showing off the rich black-and-white of Outside the Law and the shadowy cinematography of Russell Metty on The Female Animal and Ride the Pink Horse. Three of the movies are in conventional ratios, but The Female Animal—definitely not a B-picture in aspirations—was shot in CinemaScope.

The commentaries and visual essays are mostly of a very high standard, and occasional repetitions of imagery actually serve to strengthen the connections between them.

directors: ‘Calcutta’: John Farrow. ‘Ride the Pink Horse’: Robert Montgomery. ‘Outside the Law’: Jack Arnold. ‘The Female Animal’: Harry Keller.

writers: ”Calcutta’: Seton I. Miller. ‘Ride the Pink Horse’: Ben Hecht and Charles Lederer (based on the novel by Dorothy B. Hughes). ‘Outside the Law’: Danny Arnold. ‘The Female Animal’: Robert Hill.

starring: ‘Calcutta’: Alan Ladd, Gail Russell, William Bendix, Marina Tanev & Lowell Gilmore. ‘Ride the Pink Horse’: Robert Montgomery, Wanda Hendrix, Andrea King, Thomas Gomez & Fred Clark. ‘Outside the Law’: Ray Danton, Leigh Snowden, Grant Williams, Onslow Stevens & Raymond Bailey. ‘The Female Animal’: Hedy Lamarr, Jane Powell, Jan Sterling, George Nader & Jerry Paris.