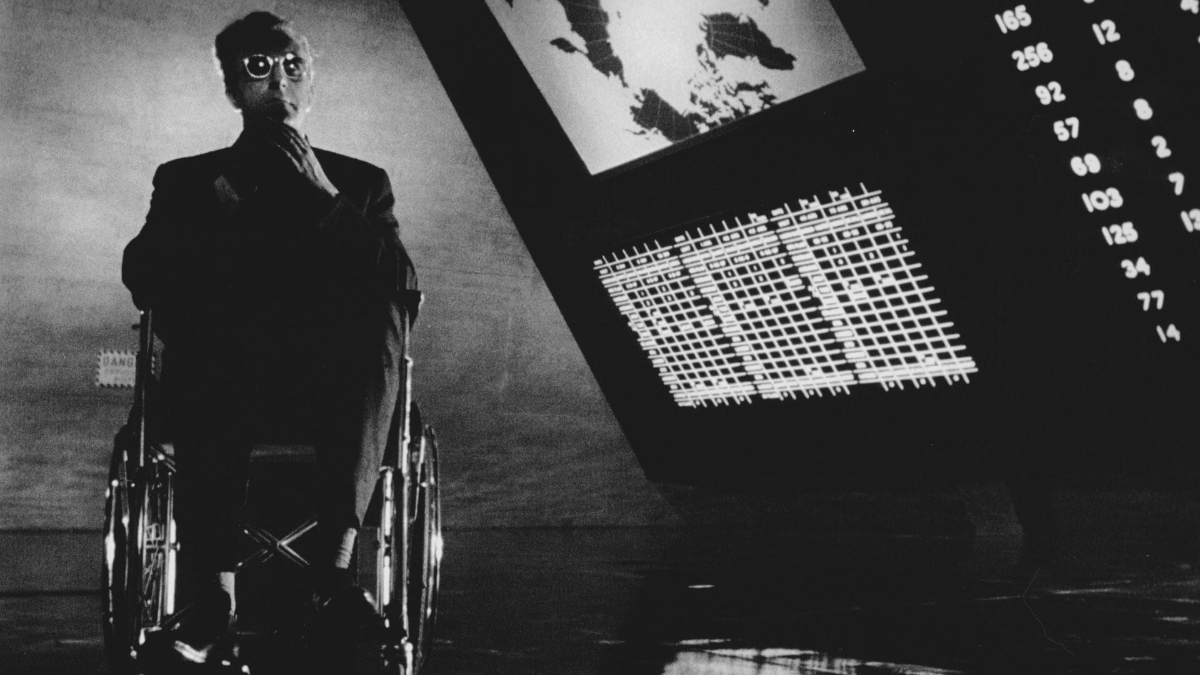

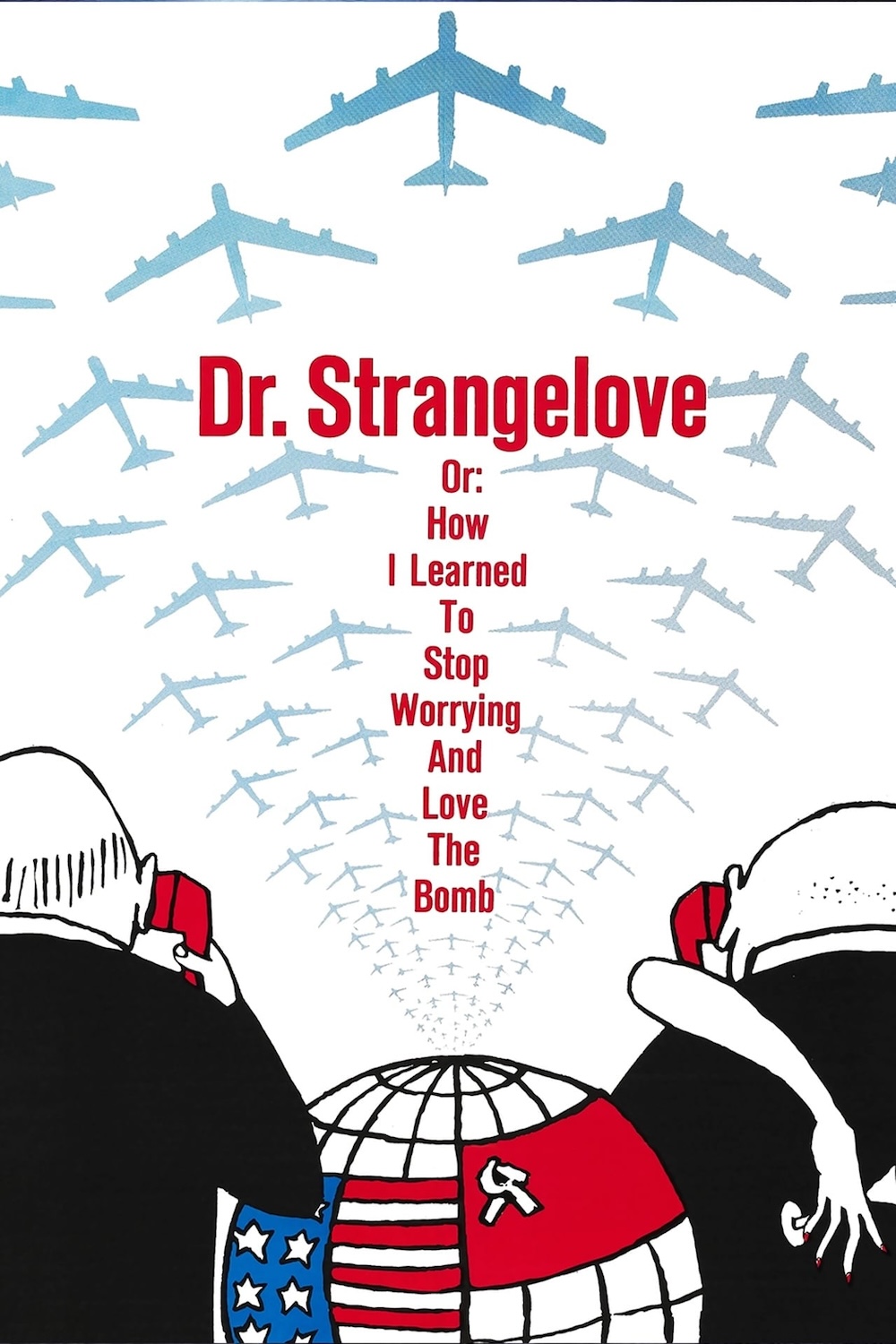

DR. STRANGELOVE OR: HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB (1964)

An insane US general orders a bombing attack on the Soviet Union, triggering a path to nuclear holocaust that a war room full of politicians and generals frantically tries to stop.