DOCTOR WHO, 12.10 – ‘The Timeless Children’

As the last remaining humans are ruthlessly hunted down by Cybermen, Graham, Ryan, and Yaz face a terrifying fight to survive as lies are exposed and truths are revealed for The Doctor...

As the last remaining humans are ruthlessly hunted down by Cybermen, Graham, Ryan, and Yaz face a terrifying fight to survive as lies are exposed and truths are revealed for The Doctor...

It’s a handy thing, a ventilation shaft. Everyone has them, even the Cybermen, and in the opening of Doctor Who’s Series 12 finale “The Timeless Children”, it quickly helps resolve the previous episode’s cliffhanger. Surrounded by masses of Cybermen? No problem, Bescot (Rhiannon Clements) stumbles upon and opens a convenient ventilation shaft cover and she, Graham (Bradley Walsh), Yaz (Mandip Gill), Ruvio (Julie Graham), and Yedlarmi (Alex Austin), facing certain death, attempt to make their escape. Karma being what it is, Bescot’s denied the chance to seize victory from the jaws of defeat and is shot down as the others flee into the vast Cyber-carrier. It’s but a mere footnote within an episode that writer Chris Chibnall has set up to signal the direction he wants Doctor Who to take and finally carry his authorial stamp as showrunner. The issue here is that, while Chibnall takes delight in retconning some long-debated aspects of lore, he leaves behind several narrative loose ends.

From the outset, given what we’re eventually presented with and the often rather odd structure and dynamics of the script, it falls to director Jamie Magnus Stone to carry us through the 65-minute running time. Stone’s direction, editing, and visual sensibility add conviction to this broadly satisfying series conclusion. I’ll pick up on some of this as I go along, but Stone is certainly one of the strongest directors the series has had since Rachel Talalay.

Meanwhile, The Master (Sacha Dhawan) and The Doctor (Jodie Whittaker) cross the Boundary to arrive on the devastated Gallifrey. “Look upon my work Doctor, and despair” he announces, paraphrasing our old friend Percy Bysshe Shelley’s 1818 sonnet Ozymandias. It’s appropriate, given that the sonnet is about the fall of a great civilisation; the pretension and hubris of those who once held great power brought down by history and the passage of time. Here, it’s the downfall of the Time Lords at the hands of a renegade who validates his own actions after uncovering their darkest secret. The Doctor and The Master’s innocent play as children in the streets of Gallifrey have become bitter memories for him. Her inevitable question, what the reason was for destroying her home, is met with a childish “not telling you” from The Master. It’s all a game to him despite his rage; a rage he’s attempted to quench with death and destruction.

Back on the Cyber-carrier, the death of Bescot has given the remaining humans pause for thought and a desperate need to hide from Cyberman surveillance. Ruvio’s also discovered a transmat and, if they could get to it, it’s their only means of travelling down to the planet. Graham suggests a rather ghoulish plan to “use their armour so they don’t notice us.” In a sense, this reflects the way younger viewers have always pretended to be the monsters in Doctor Who—a tradition that began with Ian Chesterton’s Dalek impersonation in “The Daleks” (1963), to effect an escape from a prison cell. As Ruvio and Yedlarmi undertake the unpleasant task of preparing their host bodies, Yaz and Graham are given a welcome moment of reflection with a warm, humourous exchange of mutual appreciation. It’s a quiet scene, well played by Walsh and Gill, that brings a rare sense of empathy to both characters, given the inhuman environment they’re trapped in.

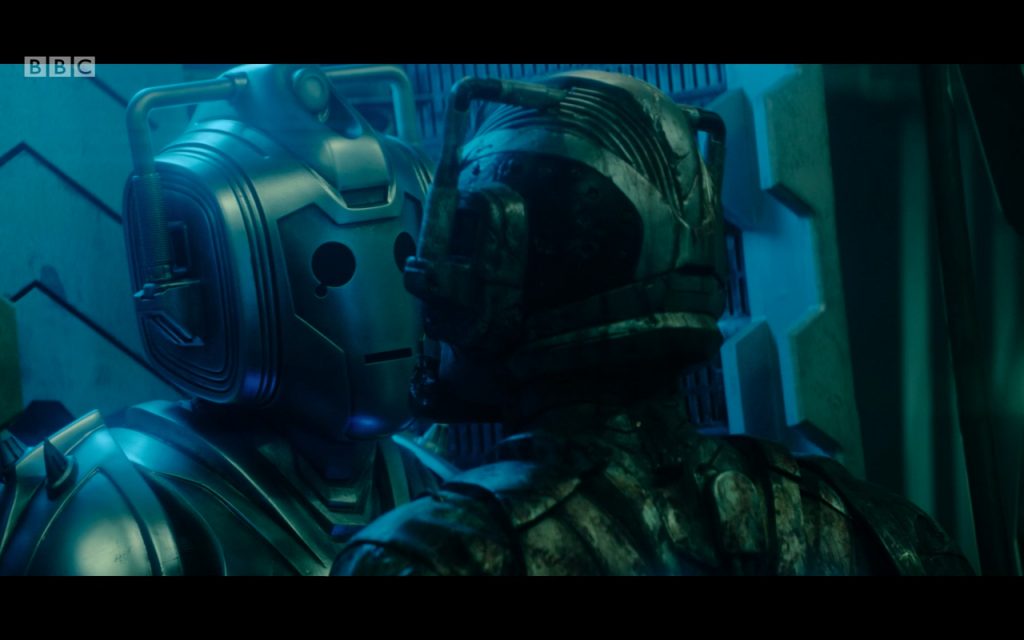

After scooping out what human remains are left inside the Cyber armour and disguising themselves as Cybermen, Jamie Magnus Stone gives this subplot enormous power when, alerted to their presence, Ashad (Patrick O’Kane) comes in search of them. Stone flips between the inside of the armour, showing their human impostors looking out through the iconic eye, with its tear design, as Ashad searches the ship. This provocation results in a sequence of close-ups, cutting between a real tear rolling down Yaz’s face, the tightening of real lips, and their exterior, expressionless metal equivalents while their hiding place is threatened with discovery. It’s a great visual contrast between human and machine expression and is underlined, later, when Ashad reveals to The Master that his plan for the Cybermen is to purge them of remaining human components and thus turn them into robots. The Master has other ideas, naturally…

On the planet below the Cyber-carrier, Ko Sharmus (Ian McElhinney), Ethan (Matt Carver), and Ryan (Tosin Cole) prepare to defend themselves from squadrons of Cybermen transporting to the surface. Sharmus, an old general who’s prepared an armoury for such eventualities, dishes out various weapons and bombs with the caveat that “you can be a pacifist tomorrow. Today you have to survive.” It’s worth bearing in mind, considering his later line when he’s on Gallifrey, “there must be a few last things I can blow up before I’m done”, that he will eventually take the route of self-sacrifice by the end of the episode. With Ryan’s triumphant slam dunk using a bomb to wipe out a squad marching toward him, there’s a call back to the opening of “Spyfall”, when Ryan’s friends were shooting some hoops, remarking on his recent absence and we were reminded he still had his dyspraxia to deal with. However, he, Sharmus and Ethan are eventually overwhelmed and it seems all is lost until Graham, Yaz, Ruvio, and Yedlarmi (posing as Cybermen) come to the rescue.

As these two plot strands converge, with the Cybermen setting course for Gallifrey and the remaining human characters crossing the Boundary to rescue The Doctor, the episode’s raison d’être is given pride of place. After revealing that he’s invited the Cybermen through the Boundary to conquer what remains of Gallifrey, The Master gives The Doctor an awful lot more to deal with. The notion that “everything you knew was a lie” is predicated on matters concerning the founding of Gallifrey, sequestered away in the recesses of the Matrix, the repository of all Time Lord knowledge, containing the lived history, experiences, and memories of their race. He’s already referred to their childhood games and a past encounter “assassinating Presidents” in the Panopticon during “The Deadly Assassin” (1976), where The Master’s agent Goth also fought The Doctor within the surreal world of the Matrix.

Again, he claims he “was just playing” when he hacked the Matrix. Always the child, pulling wings off flies, The Master stumbled across a hidden history of the Time Lords. Despite The Doctor trying to appeal to his better nature (and he admits he hasn’t got one) to save her friends from the Cybermen, he uses a paralysis field so that can he drag her into the Matrix to reveal what fuelled the angry destruction of his own people. You’d also be forgiven for thinking that a paralysis field has also suddenly taken hold of the story’s structure at this point.

At the heart of the episode are several long flashback sequences (running to about five minutes apiece) featuring characters who aren’t given any dialogue and whose actions and thoughts are transmitted through voice-over narration. Not only that, but we also have significant information dumps about the founding of Gallifrey. It’s incredibly risky on Chibnall’s part to trust a mainstream audience will tolerate this mode of storytelling, using this amount of the mythology surrounding the Time Lords. There is every chance viewers just won’t care.

Chibnall does have a tendency in his work, particularly on a series like Broadchurch, to stop the action and, during such procedurals, have characters narrate incidents during flashbacks, to provide versions of the story from their viewpoint that were alluded to in earlier lines of dialogue. It also hinges on the performances of the lead actors, Dhawan and Whittaker in this case, who have to carry all of this material in two-handers or via off-screen narration. It’s to their credit that they maintain our interest despite their very brief appearances together in media res during the flashback sequences.

Once he gets The Doctor to the Matrix, we’re given a whole new perspective on Gallifrey’s past. It’s a hidden history that specifically affects the one established and that already exists between The Doctor and The Master; a new history that “does mean something” beyond their friendship, studying at the Academy and their continuing feuds. For The Master it goes to the “rage and pain in my hearts”, a reason why he has committed genocide. It starts, akin to a traditional fairy or folk tale, with “once upon several times” and concerns an explorer, scientist Tecteun (Seylan Baxter), one of the indigenous Shabogans of “little regarded, sparsely populated” Gallifrey, who travels beyond her home to see distant galaxies. Rather like The Doctor, her impulse was to see and understand the universe. On a deserted, distant planet she finds a child, abandoned at a gateway under the Boundary to another universe or dimension. As the young Master, during his own initiation into the Time Lord Academy, painfully experienced the untempered schism of the space and time vortex in “The Sound of Drums” (2007), she glimpses the infinite through the Boundary, supposes the child came through the gateway and decides to adopt her as her own. Returning to Gallifrey, an accident reveals that the child, who would not yield her origins under Tecteun’s examinations, can survive fatal injury by regenerating.

The image of play is again at the centre of the narrative, as Tecteun’s mysterious child plays with her friend, like The Doctor and The Master played in the streets of Gallifrey, until the accidental fall from a clifftop. It parallels Brendan’s own fall and recovery in “Ascension of the Cybermen” and is key to understanding the relevance of Brendan’s story set in Ireland. Essentially, this evolves into a creation myth as Tecteun experiments on her adopted child to unlock the secrets of regeneration. Her medical ethics and morals are rather questionable. The child regenerates several times as the ageing Tecteun, like Mary Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein, becomes determined to crack the secrets of regeneration, of life after death, and create a race in the image of her orphan child.

Meanwhile, we learn why The Master has offered the red carpet, “drenched in the blood” of Time Lords, to the Cybermen. He’s after the Death Particle—a weapon contained inside Ashad, fashioned within his heart by the Cyberium, that’ll wipe out all organic matter and allow him and the Cybermen to ascend to “full automation.” It’s a continuation of the themes set in motion by “The Haunting of Villa Diodati”, with the creation myth of the Cybermen and the Time Lords framed as a fireside ghost story, where the orphaned Ashad and the mysterious child found by Tecteun are metaphors for overreaching technological interventions in humanoid biology and, as Fiona Sampson notes, “their ethical and social consequences.” For The Master, the ultimate mad scientist, this is not about boring robots, it’s about reanimating the bodies of dead Time Lords and splicing them with Cyber bodies to create a race of Cyber-Masters capable of regeneration. Not only does he punish the Time Lords, those Ozymandiases of Gallifrey, for their hubris and arrogance but, to conquer the universe, he enshrines one of their enemies with what remains of their power. As Shelley noted in Ozymandias, power is only temporary and those that have it are deceiving themselves. At least the Cyber-Masters dress for the occasion, fitted out with camp metal Time Lord collars and swishing cloaks.

Back to Tecteun, then. She works obsessively to isolate the genetic imprimatur for regeneration from her ever regenerating child, the timeless children of the episode’s title. By testing it on herself, she becomes the first Time Lord of Gallifrey and the Citadel-dwelling Shabogans, having discovered the ability to travel in space and time, are elevated to a self-appointed ruling elite, bequeathed the genetic legacy to regenerate twelve times, after “the foundling becomes the founder” of the Time Lord race. That mysterious, timeless foundling is The Doctor. No wonder The Master was pissed off after hacking the Matrix! He’d discovered he owes his very existence to The Doctor.

Ashad is cut down to size by The Master’s Tissue Compression Eliminator and, although the Death Particle is still contained in his doll-like form, the Master had gambled on it to activate and wipe out all organic life. Clearly, he would’ve been happy with Plan A. His Plan B is to become The Apprentice to the Cyberium as he announces “I deserve to be your business partner because I have performed well in all tasks.” Fleeing from the incapacitated Ashad, the Cyberium enters The Master, where its strategies and history can be combined with his Time Lord knowledge to direct his Cyber-Masters in the conquest of the universe.

The Doctor is adamant she knows her own life and accuses The Master of lying to her. However, he claims her “life has been hidden” from her to maintain a pure and noble Time Lords creation myth and, although she remembers their early life together at the Academy, it wasn’t her first life. Desperate to know why the Time Lords lied and covered up her true identity, he tells her he always knew she was different, was special, and that the truth means that “a little piece of you is in me. All I am is somehow because of you.” Given the trail of destruction he has unleashed upon Gallifrey, it’s something he is unable to bear. After attacking him, she demands to know the rest.

Apparently, Tecteun and her child, The Doctor, are co-opted into The Division, a clandestine Time Lord organisation whose function is to overrule policy and intervene in the affairs of other races. We know that in the past the Time Lords did quite a bit of intervening and perhaps this is Chibnall’s way of squaring that with the true identity of The Doctor. The sequence is interrupted by flashes from the sub-plot set in Ireland. It would seem the whole sequence from “Ascension of the Cybermen” is a trace of her past life with The Division, buried in the Matrix but visually filtered by Tecteun to make it seem unremarkable to anyone looking.

It’s the only trace of what seems to be a series of significant early lives prior to The First Doctor we originally encountered in the junkyard in 1963. The clock we saw in the police station is a gift from The Division, or the Garda in the filtered version, and presented to Brendan, the avatar representing The Doctor. Hence, his fall from the clifftop and recovery is a cloaked version of the timeless child’s own history and how The Doctor’s former lives were deleted by the Time Lords. The Master then transmitted that trace of her past to The Doctor as she tracked the Cybermen. Is that trace just a clue or an apology from Tecteun? Presumably, we’ll see The Division explored further in the next series?

This exposition, carried in the main by an always watchable Sacha Dhawan, is a huge amount to foist upon a single episode and on an audience who may not know the entire Time Lord backstory. Specifically, it will be divisive to many long-term fans as it effectively rewrites Time Lord history and uses The Doctor’s genetic code as the urtext for their existence. Previously, she was simply a member of that race who decided to run away from their hidebound society and explore the universe. However, there were suggestions, certainly during the final series of the classic show overseen by script editor Andrew Cartmel, that The Doctor was something more than a Time Lord, with a past shrouded in mystery again. Chibnall has returned to this premise and posits The Doctor is again unknowable, her appearance at the gateway unexplained, her chain of lives prior to The First Doctor’s appearance erased by The Division.

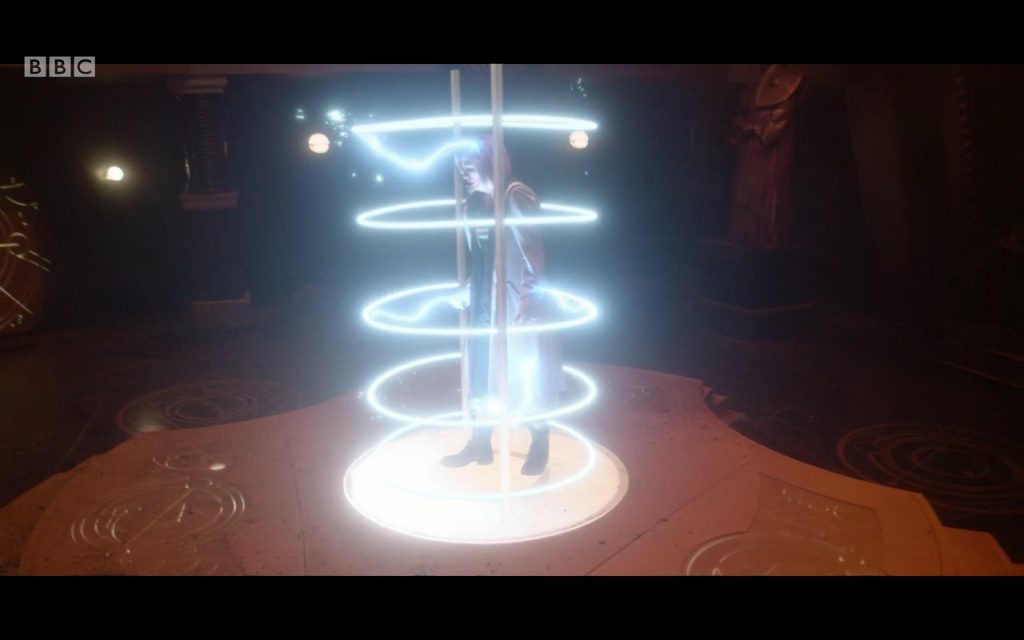

As if to underline this, The Doctor, apparently defeated, meets herself again, in the form of Ruth Clayton (Jo Martin). In answer to some of the questions that fans may have posed and acting as a form of assurance, she encourages The Doctor to look beyond the confusion about her unknown past lives and to focus on what The Doctor represents. “Have you ever been limited by who you were before?” she asks. Of course, she hasn’t. She’s needed and it’s time to rejoin the fight. “I know this place has blown your mind. Maybe you should return the compliment?” suggests The Ruth Clayton Doctor. “All this history. All these lives, it’s too much stimulus,” The Doctor concludes. She promptly uses her amassed memories to flood the Matrix and to deny its reality.

It’s a glorious sequence, with a very rare example of the main title theme being used to score a scene within an episode, that flashes through what seems to be hundreds of clips of past adventures, past companions, past enemies and monsters and, finally, onto past Doctors. One wonders if Chibnall’s strategy here was to fix a few anomalies while he was at it. It can only explain what happens when we get through the various Doctors, all present and correct (well, not Peter Cushing, but who’s to say his Doctor isn’t a past incarnation now that it seems The Doctor has had many, many past lives?), and we flash beyond William Hartnell as the First Doctor. We see the various timeless children looked after by Tecteun, progressing from the young girl she discovered at the gateway to the adult male at the meeting of The Division, and then, surprisingly, to the range of faces seen in the mind battle between The Doctor and renegade Time Lord, Morbius in “The Brain of Morbius” (1976). That’s seven more faces. Plus Brendan and the Ruth Clayton Doctor at the end of the sequence.

To go back and confirm the “Morbius” continuity at the same time that he’s also clearing the decks of Time Lord history will certainly ensure Chibnall’s notoriety. Depending on your opinion, he’s either the showrunner who ruined Doctor Who or injected something very new into it. The First Doctor is still the first and Hartnell’s legacy is safe and sound. The question remains as to where the ‘Ruth Doctor’ fits in as she’s at the end of the sequence featuring the timeless children. Does this suggest that The Doctor was at that point being regressed by The Division to her life as a child? And was the Ruth Doctor on the run from The Division in “Fugitive of the Judoon”, hiding away from them on Earth? This also throws up questions about the Time Lords granting new life cycles to both The Master and The Doctor in the past? If The Doctor is actually immortal and has unlimited regenerations, were the Time Lords pulling a fast one? Could they actually grant new life cycles given Tecteun’s limit?

So many questions that the last act of the episode seems almost perfunctory in nature. The Doctor escapes from the Matrix, is reunited with her “fam”, a load of explosives and a plan. Her companions successfully blow up the Cyber-carrier (featuring some excellent VFX) and thus eliminate any opportunity for The Master to create a vast army of “endlessly regenerating” Cyber-Masters. I assume it’s The Doctor’s genetic imprint that’s been used to create them and they’re not limited to twelve regenerations? Very conveniently, Ruvio recalls the myth of the Death Particle as The Doctor racks her brains about Ashad’s claim that “the death of everything is within me”. She challenges The Master to one last standoff, having equipped herself with the miniaturised Ashad and a bomb, with a “hand detonation only” cliche, to set off the Death Particle. It’s the only way to destroy the organic Time Lord material of the Cyber-Masters but, rather inconveniently, it’ll kill everyone else.

She packs everyone off in a TARDIS and sends them to safety on Earth. It’s then just her, The Master and his Cyber Masters. Except, of course, The Master calls her bluff. She simply doesn’t have the will to detonate the bomb. Equally convenient, old Ko Sharmus is willing to step in so that she can live. If we’d had a really emotional connection to Sharmus then this may have had more impact. It simply shows up the problem with Chibnall overreaching in this finale. The companions, the surviving humans and Sharmus are rather sidelined in favour of action and the massive information dump about Gallifrey and the Time Lords. While The Doctor’s departure from the TARDIS does strike an emotional chord, both in her scene with Yaz and her entreaty to all of them to “live great lives”, there’s been too little of an emotional connection with them. Although some dialogue has signalled Sharmus’ do-or-die approach to matters, we don’t really feel that aggrieved when he finds The Doctor, offering to emulate Obi-Wan Kenobi and sacrifice himself. It’s also a well-used motif to get The Doctor out of such situations, often to prevent an act of genocide, and defuse the entailing tricky moral implications.

Once we’ve seen everyone home safely, The Doctor’s pinched another TARDIS to get back to where she parked her own (leaving one on Earth and on the planet seems rather cavalier), and the Judoon have shown up and flung her into a cell on what looks like Shada, the Time Lord’s own prison facility, the important question is: just who is The Doctor now? Has she “become death”, as The Master suggests, quoting Robert Oppenheimer as he clapped eyes on the Trinity nuclear test (Gallifrey’s disintegration at the end of the episode looks like a mushroom cloud).

It might be worth looking at Oppenheimer quote “Now, I am become death, destroyer of all worlds”, a somewhat rough translation from the Bhagavad-Gita Hindu scripture. It is dialogue between the warrior-prince Arjuna and his charioteer Lord Krishna, an incarnation of the god Vishnu. Arjuna faces an army of his friends and relatives and is caught in an impossible dilemma about whether to fight them. Krishna offers an alternative philosophy, allowing Arjuna to fulfil his destiny despite personal complications.

This is Dharma. Krishna suggests it’s Arjuna’s duty to fight. The people that die are truly killed by Krishna, not Arjuna. They are all fated to die. Arjuna is just the instrument. For Krishna himself is time or death. The Master merely wants The Doctor to become his instrument, to become death. It would please him if she did her duty and killed them all. Certainly, we could see this as a variation on the themes at the heart of the story, the idea that reincarnation or rebirth defeats death but time eventually destroys all things. The Doctor lives on as the timeless child but the Time Lords are gone once Ko Sharmus presses the button to fulfil The Master’s death wish. Sharmus rather than The Doctor accepts The Master’s offer to “become me” and his reasoning is that he must accept responsibility for starting all this, having been part of the resistance unit that sent the Cyberium back though time and space.

As Matthew Sweet pointed out, there’s also something of Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself in her declaration to The Master. He’s not broken her because she now has the gift of “myself”, she is now more than she was and contains “multitudes more that I ever thought or knew.” She tells The Master “I am so much more than you”, suggesting that not only has she has many more incarnations that she never knew about but that genetically she is more than he is. He’s a Time Lord, limited to a wonky regeneration cycle, and she is a mysterious, immortal alien who can go on forever.

However, the latter, which is a neat bit of rejigging of the series’ main principle and frees it up a bit, seems to get written over by the implication that we’ve also swapped one great big bit of canon for another. We may end up being constrained by the fact that The Doctor was part of some dubious Time Lord organisation and have loads of other Doctors popping up all over the place. The Ruth Doctor could be implicated in why The Doctor had her previous memories wiped and I suspect we’ll be seeing more of her again as that story has been left inconclusive. I also expect The Master to return. His last line “all of you, through here now” implies he was making a quick exit into a TARDIS.

Don’t get me wrong, I really enjoyed the episode. It has its problems, in terms of how to use TV to tell a story in flashback, in leaving your central character as someone to be talked at rather participating in the making of her own story, and is a further example of how character development needs to have an emotional underpinning. However, it’s sustained by decent, if often barmy ideas, two rather good performances from Sacha Dhawan and Jodie Whittaker (despite The Doctor being left powerless to explore her own hidden past), impressive production design, VFX, and costumes. Uneven as it is, director Jamie Magnus Stone deserves the credit for managing to keep 65-minutes of wild ideas moving, and he gives them convincing scale and pacy, visual interest.

writer: Chris Chibnall.

director: Jamie Magnus Stone.

starring: Jodie Whittaker, Bradley Walsh, Tosin Cole, Mandip Gill, Ian McElhinney, Julie Graham & Sacha Dhawan.