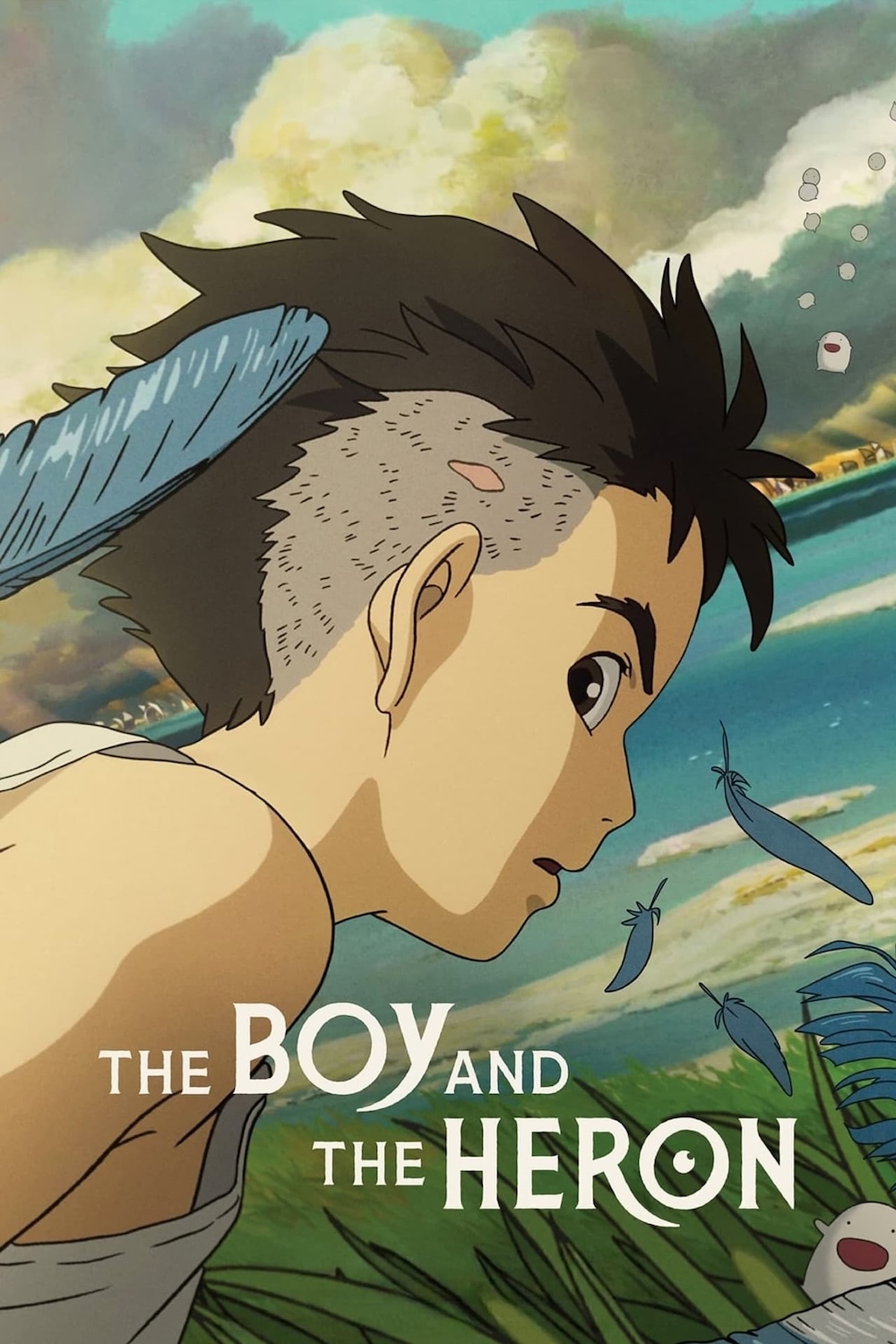

THE BOY AND THE HERON (2023)

A young boy, yearning for his deceased mother, ventures into a world shared by the living and the dead.

A young boy, yearning for his deceased mother, ventures into a world shared by the living and the dead.

It’s no coincidence that Guillermo del Toro introduced The Boy and the Heron / 君たちはどう生きるか at the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival, echoing a sentiment he’s championed since promoting his own Pinocchio (2022) adaptation: “animation is film” and not just a genre that entertains children.

This passion extends to acclaimed Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki, whose works—from sweeping epic Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) to the universally adored Spirited Away (2001)—combine dazzling visuals with profound emotional resonance. Miyazaki’s animations are testaments to the artistic and technical brilliance animation can achieve.

When Miyazaki declared his retirement after the release of The Wind Rises (2013), his legacy as a filmmaker was already firmly established. While it was a fitting farewell, the artist’s yearning to create one last masterpiece for his grandson and future generations remained. A decade after his ode to the allure of flight and the fragility of dreams, Miyazaki and his Studio Ghibli team have returned with yet another endlessly imaginative masterwork. Inspired by Genzaburo Yoshino’s novel How Do You Live?, the film is both a valedictory to his career and an invitation to the audience to embark on their own introspective journey. The Boy and the Heron is a mesmerising and relentlessly imaginative adventure that combines the thrills of a child’s grand adventure with the poignant contemplations of an elderly man.

Set during the Pacific War, young Mahito (Luca Podovan) is forced to flee Tokyo after his mother’s death. His father, Shoichi (Christian Bale), relocates them to the countryside, starting a new life with his wife’s sister, Nasuko (Gemma Chan). As Shoichi becomes increasingly absent, Mahito’s grief over his mother plunges him into a constant melancholy. In this vulnerable state, the boy encounters a mysterious Grey Heron (Robert Pattinson). The imposing bird assures Mahito his mother lives and lures him to an ancient tower at the property’s edge. Inside the abandoned structure, Mahito meets his magical Granduncle (Mark Hamill), who rules over an unexplainable realm of fantastical wonders. However, Mahito soon realizes his visit holds a much deeper significance.

While many Ghibli fans consider the original Japanese versions superior to the English dubs, after comparing both versions of The Boy and the Heron, I find the English adaptation surprisingly faithful and nuanced. The entire ensemble establishes their personalities and captures each character’s subtle emotions. Luca Podovan (No Hard Feelings) delivers a delightful performance as young Mahito. He imbues the character with a heartwarming fragility, beautifully capturing his timid and insecure nature. His introspective and contemplative demeanour makes him a distinct protagonist compared to the fearless female leads of Princess Mononoke (1997) and Spirited Away. However, as the story progresses, Podovan adds a fascinating energy that complements Mahito’s emotional depth.

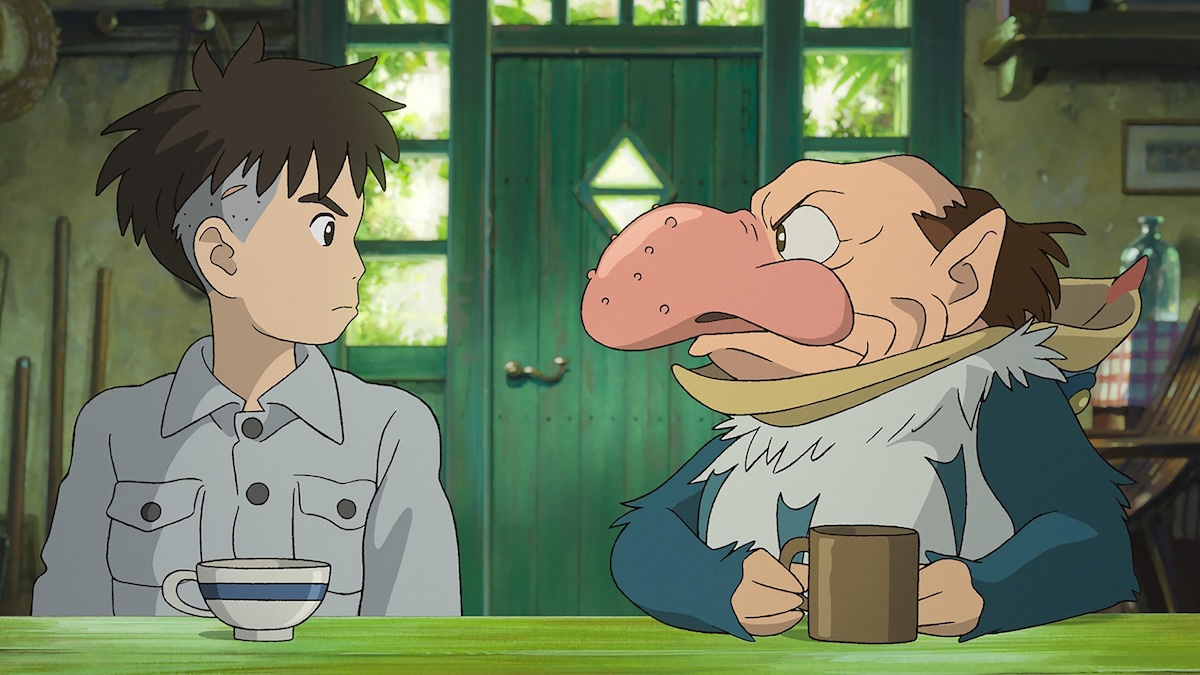

Though Florence Pugh (Oppenheimer), Christian Bale (Howl’s Moving Castle), Mark Hamill (Star Wars: Return of the Jedi), Willem Dafoe (The Lighthouse), and Gemma Chan (The Creator) all deliver seamless performances and breathe life into Miyazaki’s beloved characters, they are somewhat overshadowed by Robert Pattinson’s (The Batman) surprisingly infectious portrayal of the eponymous Grey Heron. With practically unrecognisable gravelly vocals, Pattinson imbues the Heron with a mischievous charm that perfectly captures the essence of the character. He elevates what could have been a forgettable companion into a truly memorable creation, one that’s both delightfully unhinged and endearingly charismatic.

Mirroring the iconic visual tapestry of Spirited Away, The Boy and the Heron boasts some of Studio Ghibli’s most breathtakingly beautiful imagery. A testament to the power of traditional hand-drawn artistry, Miyazaki imbues each character with a spiritual vitality that transcends mere mechanical accuracy. Nearly every frame revels in meticulous detail, peppered with subtle, beautifully human touches. Seemingly inconsequential actions, like a carp chorus erupting from the lake or the heron’s piercing gaze, are meticulously animated to infuse each character with life. The opening sequence exemplifies Miyazaki’s world-building mastery with stunning, fluid imagery. Nightmarish visions of World War II engulf a bustling cityscape, rendered in impressionistic strokes of flickering flames. Ghostly silhouettes and indistinct figures throng the scene, through which Mahito navigates in his desperate search for his mother. While most animators would likely stylise these characters as vaguely moving presences, Miyazaki infuses each with an undeniable presence, a testament to his decades-honed timing.

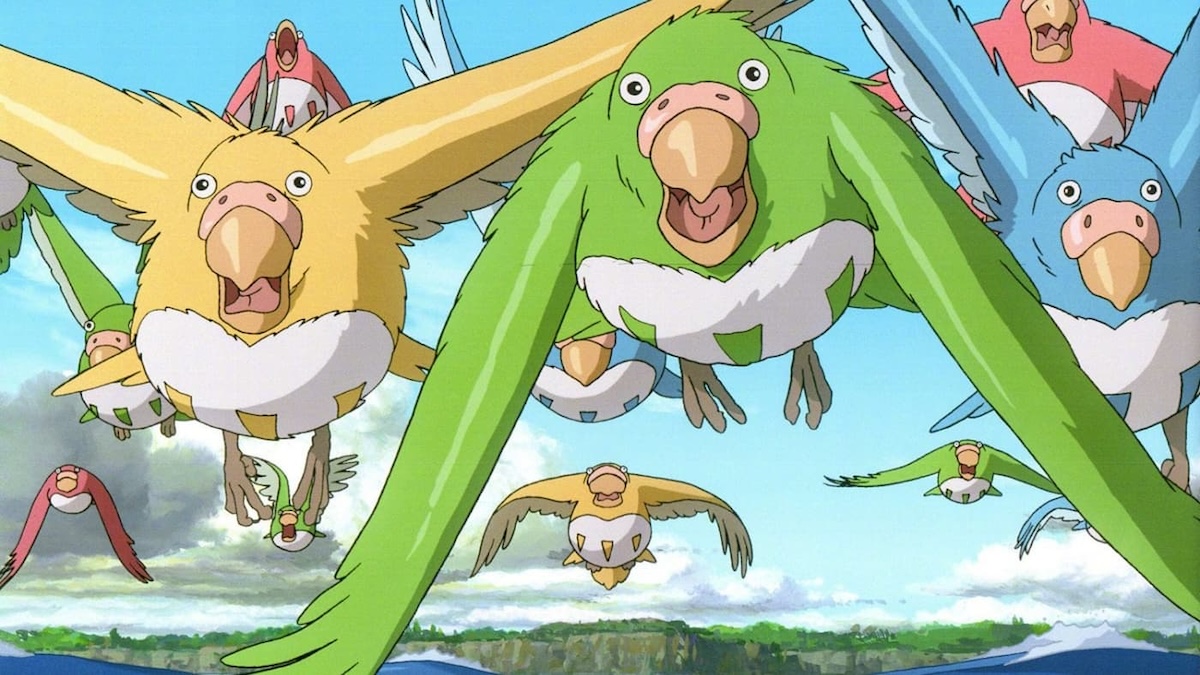

Adding his own tincture of absurdism to concepts that would envy legendary authors like Lewis Carroll, L. Frank Baum, and C.S Lewis, Miyazaki creates a world that fully extends beyond the animated pages. The Boy and the Heron is densely populated with the most indelible Ghibli characters since Ponyo (2008). Each perilous dimension our protagonist visits reveals a fraction of Miyazaki’s imagination and brims with boundless inspiration. Teeming with strange phenomena and creatures both breathtaking and wondrous, the realm encompasses vast oceans and endless fields of grass inhabited by swarms of talking pelicans and chirpingly demanding parakeets. Meanwhile, adorable little creatures called Warawara drift into the heavens before transforming into the souls of newborns. Miyazaki delivers some of his most striking compositions, each fantastical denizen inhabiting a magical realm overflowing with intrigue and creativity.

The provocative and haunting question posed by the film’s Japanese title is intrinsically linked to the philosophical concerns that underpin Miyazaki’s oeuvre. The filmmaker has spoken of his memories fleeing Tokyo during World War II, his father’s company manufacturing airplanes, and his mother’s untimely passing. It’s impossible not to view The Boy and the Heron as a kaleidoscopic and whimsical rumination, informed by the filmmaker’s own childhood memories. Mahito’s journey through the fantastical kingdom is both one of wondrous discovery and one that explores the complex emotions surrounding childhood trauma and grief. Initially, the young boy is abrasive and struggles to assimilate him into his new surroundings. While living miserably with his father he develops a fraught relationship with his maternal aunt and inflicts grievous injury to himself to avoid returning to school. However, we eventually begin to sympathise with the protagonist when we realise he’s grieving child struggling to process the inexplicable cruelty of the life he’s given.

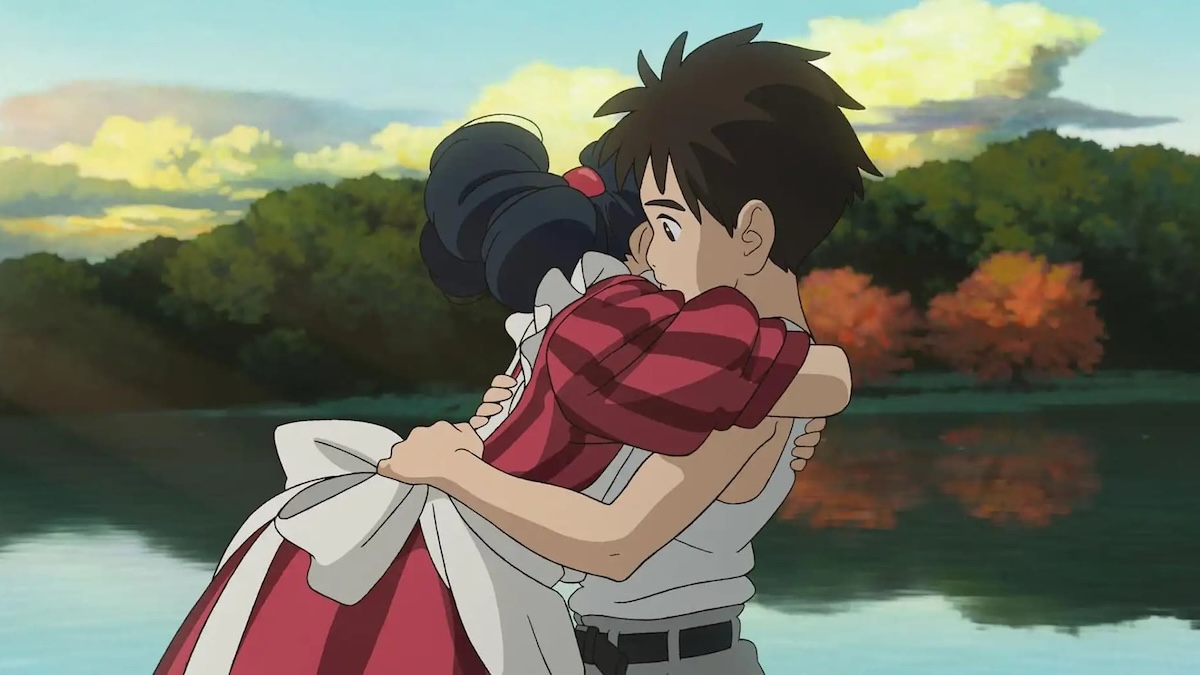

Haunted and consumed by grief after the devastating fire that took his mother’s life, Mahito finds solace in the Grey Heron’s summons to a supposedly magical tower. Desperate to escape the gaping void left by her loss, he embarks on a journey into an otherworldly realm. Guided by the enigmatic seafarer Kriko (Florence Pugh), Mahito confronts the cycles of life and death, learning to transform his corrosive grief into a cherished memory of love.

Through acceptance of mortality and the bittersweetness of goodbyes, Mahito finds the strength to embrace change with newfound hope and kindness. Though offered the throne of this fantastical land, he chooses the pain of reality, knowing its inherent meaning and enduring ambiguity. This poignant ending challenges audiences long after the credits roll, leaving them to ponder the profound impact of life’s experiences and the artistic expression that reflects them.

By unpacking The Boy and the Heron to its core, we can read it as a melancholic meditation of an ageing artist. Having secured his place within animation history and Japanese culture, Miyazaki seems to acknowledge that the industry has moved on without him. Contemporary filmmakers and studios like Hiromasa Yonebayashi (Mary and the Witch’s Flower) and Makoto Shinkai (Suzume) are now crafting the type of spellbinding imagery and metaphorical narratives that audiences once solely associated with Miyazaki, but their work marks a distinct departure from Ghibli’s signature style. In a poignant outpouring of self-reflection, Mahito’s Granduncle, perched atop his towering studio, builds structures from humble blocks. Desperately imploring Mahito to inherit his creative mantle, he yearns for a successor to reshape the world in his own image. These moments suggest that Miyazaki has accepted his own mortality and, ultimately, that Ghibli’s legacy will be balanced by the building blocks of a new generation.

Not mere animation, The Boy and the Heron is arguably one of the greatest animators in history’s profound examination of life’s intricacies, delivered through an introspective cinematic and literary fusion. This masterful work presents viewers with a resonant and timeless question that transcends the screen. Honouring Miyazaki’s signature themes and artistry, the film brims with memorable characters, astounding visuals, and heartfelt storytelling. Enchantingly inspiring, The Boy and the Heron will surely solidify its place among Studio Ghibli’s other classics.

JAPAN | 2023 | 124 MINUTES | 1:85:1 | JAPANESE • ENGLISH (DUBBED)

writer & director: Hayao Miyazaki.

voices: Soma Santoki, Masaki Suda, Ko Shibasaki, Yoshino Kimura, Takuma Kimura (Japanese) • Luca Podovan, Robert Pattinson, Christian Bale, Florence Pugh, Mark Hamill, Willem Dafoe & Gemma Chan (English).