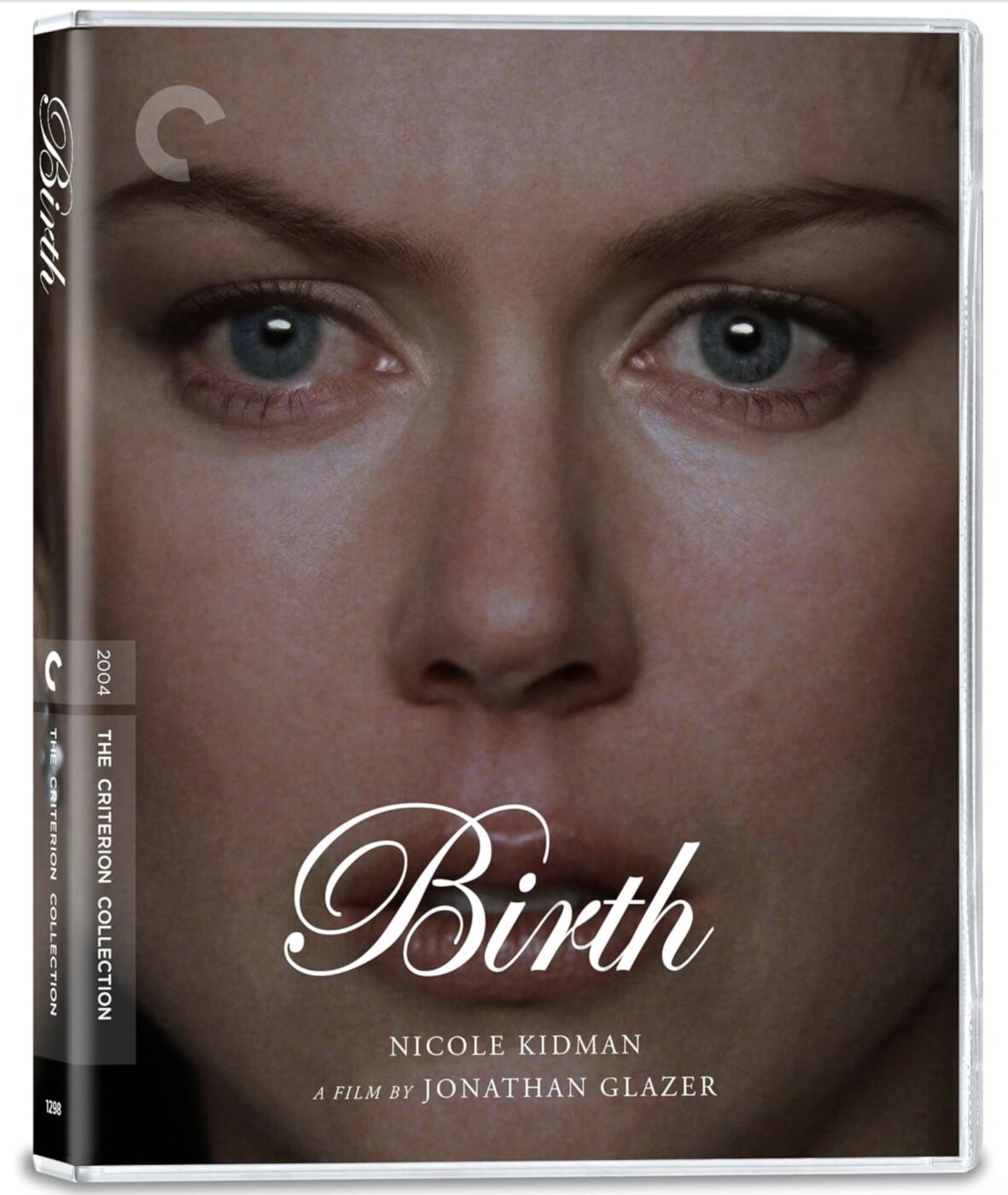

BIRTH (2004)

A young boy attempts to convince a woman that he is her dead husband reborn.

A young boy attempts to convince a woman that he is her dead husband reborn.

There are films that wield provocation like a weapon, and there are those that use it to reach something deeper beneath a potentially sensationalist surface. Jonathan Glazer’s Birth is the latter—a film that at first glance appears incendiary but instead reveals something much sadder and more emotionally complex than its controversial synopsis implies.

After jogging through what appears to be a snowy wilderness—but is actually Manhattan’s Central Park—a man named Sean collapses in a tunnel and dies from a heart attack. He is cast in silhouette and we don’t see his face, but we hear a voice we understand to be his; he tells an audience, laughingly, that he doesn’t believe in reincarnation ‘mumbo jumbo’.

10 years later, with snow and frozen ground still gripping the city, Sean’s widow, Anna (Nicole Kidman), prepares to marry Joseph (Danny Huston). After a party in an elegant midtown apartment, a mysterious young boy (Cameron Bright) appears. He’s been waiting in the lobby for the right moment. Sneaking into the apartment, he finds Anna and tells her his unbelievable truth: he is her dead husband, Sean.

Anna attempts to laugh it off, but the strangeness of the situation—and hearing her late husband’s name spoken by this interloper—gives her pause. She smiles but seems close to tears. “Are you going to play a trick on me?” she asks. “No,” he responds. He speaks flatly, factually. There’s no emotion in his voice, but his mere presence evokes a certain darkness, if not outright malice. It feels cruel. The next day, he sends Anna a letter imploring her not to marry Joseph. Suddenly, a cruel joke becomes something much more confounding.

In one of the film’s most famous sequences, Anna sits unblinkingly in the darkness of a concert hall. Glazer’s camera captures an unbroken take of her face, lost in tumultuous thought as the music swells. You can practically see the image of the boy dancing across her tear-filled eyes, his words echoing through her skull. It’s a preposterous idea, but she can’t stop thinking about it. Later, in bed with Joseph, she confesses: “He said I shouldn’t marry you.” Is it that she can only reveal this information when Joseph has laid down his guard, or does it offer her some sort of power over him? Just as her mind keeps returning to Sean, the boy himself returns again and again to the couple’s building.

The boy, who we learn actually is named Sean, lives across town. Anna and Joseph visit his parents, who are more irritated by the boy’s behaviour than they are concerned. Still, the child’s father (a brusque Ted Levine) demands Sean apologise and stay away. “I can’t,” he maintains. “You’re upsetting me,” Anna says, but Sean is resolute. He has fixed himself to this idea and is helpless to change it.

Glazer, who wrote Birth with Milo Addica and Jean-Claude Carrière, decides to make Sean’s revelation an open secret—the sort of thing you might not mention in a board meeting, but which everyone in Anna’s orbit knows about. Each person is tasked with processing this impossible problem and asking themselves what they truly believe. Sean’s belief isn’t romantic or vague: “I am your husband,” he intones. It is declarative.

Anna and Joseph’s friends are 21st-century socialites, doctors, and artists. Like her late husband, they don’t believe in reincarnation (interestingly, Glazer has stated that he doesn’t either). They sit watching string quartets in their living rooms, presumably spending their days planning the next party. Rarely do we see couples alone. Joseph only perks up when young Sean baits him by repeatedly kicking his chair. There is only sedation or anger in their world. Anna isn’t given the privacy to process the situation, let alone parse her own grief.

Here, Kidman recalls her earlier character Alice Harford, the frustrated wife in Eyes Wide Shut (1999). But if Stanley Kubrick’s film positioned Alice as an agent provocateur with the power to collapse the walls between reality and fantasy, Anna in Birth keeps things closer to her chest, perpetually locking her feelings away in shame.

Soon, Sean’s persistence and declarations of love begin to break through Anna’s delicate surface. It doesn’t help that Joseph is so passive and ineffectual. “He loves me,” Anna accepts, but it isn’t enough. Though we never see Anna with her late husband, we’re clued into an all-consuming passion that has been displaced by death and now has nowhere to go.

Glazer doesn’t linger on Anna’s dissatisfaction, but we learn of her pain by the mere fact that she even entertains the notion that this 10-year-old child is her husband. Joseph may love her, but she is missing something deeper than dutiful affection. A person wouldn’t embroil themselves in something so disturbing if they weren’t already in a very troubled place. Anna doesn’t possess a domestic bliss that is being shattered; there is no heaven here to be destroyed.

Instead, young Sean is a splinter, digging into the flesh until Anna has no choice but to acknowledge the disappointments in her life. As Anna, Kidman seems most content lingering under the surface, sneaking off to clandestine meetings with the boy in the spot where her husband died. Her version of acknowledging the nightmare her life has become is to delve deeper into the unknown.

Anna and her family recognise the transgressions that arise from entertaining Sean’s claims. But in this strange relationship, Anna regains a sense of control and intimacy that no one else understands. If she and her late husband were truly made for each other, every other person will seem like a stranger on the other side of thick glass. No one else can provide the feeling that their relationship elicited.

Glazer isn’t afraid to let his audience stew in discomfort. As Anna and the young Sean sit in a diner eating ice cream, she eyes him with suspicion but carries an intangible flirtatiousness. Perhaps no one made her feel as beautiful as her husband did, and this bizarre bastardisation of their dynamic can be squeezed for a few drops of flattery. She speaks of wanting to “break the spell”, but it’s Anna who is under the spell; it’s her own fantasy she is unable to see clearly.

She takes a bite of the boy’s ice cream in a distinctly uncomfortable moment loaded with intimate suggestion. Suddenly, Anna isn’t testing the boy—she is testing herself. Moments like this follow, including a scene in which the two take a bath together. She stares at him, trying to make sense of him, and herself.

Her family’s fears grow as Anna succumbs to the fantasy—a relationship that acts as a metaphor for any number of romantic delusions. The brother of the late Sean gives the boy a test, asking him to prove his identity. The boy knows where they were married and where they made love in her mother’s apartment.

But what he knows is by the by: Birth is not a film about solving a mystery. Glazer is less interested in providing answers than in assessing how people respond to the impossible. As such, the third act is the film’s weakest, evading a definitive resolution. While it isn’t a film’s responsibility to provide answers, the brilliance of the concept does dissipate slightly after the hour mark.

Birth can be purposefully punishing. People ask young Sean the same questions repeatedly: Who are you? Why are you saying this? How do you know all this? The answers never change. He is Sean. He is her husband. He loves her. Anna’s mother and sister (Lauren Bacall and Alison Elliott) try to physically stop her from seeing the boy. “It’s illegal,” she’s reminded. Bacall delivers the funniest line of the film in a moment of repose: “I never really liked Sean.”

With Kidman’s confounding performance, we’re never entirely sure whether she’s on the cusp of recognising her own madness or simply telling us what we want to hear. She reassures her family, then speaks to young Sean about running away together.

Glazer is interested in the philosophical implications of never-ending love rather than in casting aspersions; he trusts his audience to know that Anna’s actions are abhorrent. Birth isn’t about right or wrong; rather, it’s about the ways we can be entirely ruined by another person—by love, obsession, and devotion. We see Anna’s actions as clearly wrong, but we’re given the space to understand them, which is entirely different from justifying them.

Just as the Nazi commandant in Glazer’s The Zone of Interest (2023) retches with sickness, Anna is trapped within a prison of her own making. Glazer and the late cinematographer Harris Savides present shots of people totally alone in their environments—stunning still photos of straight, clean lines and oppressive architecture. Anna sits in a luxurious marble lobby, contemplating her move, while young Sean’s mother stands helplessly in her shabby kitchen. Both are stuck in a time and place from which there seems no escape. Apartments here are as horrifying as the marble floors in The Zone of Interest.

In these fleeting tableaux, Glazer taps into the concept of eternity. If the idea of unending love has traditionally been the ultimate romantic expression, here it is horrifying. It is love as obsession—something that, in its absence, destroys us. It is a love akin to possession.

“I’m not your stupid son anymore,” Sean says to his mother. We must all learn to accept the changed feelings of others, and that we cannot control or truly know what is going on in another person’s head. Birth haunts not like a film about a ghost, but like a film that is a ghost—a memory of a memory. Glazer comes close to transgression, but his purpose is to explore emotional despair and the terror of having your identity swallowed by the void left behind by the one who was supposed to be yours forever.

USA • UK • GERMANY | 2004 | 100 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

Shot on 35mm film, Birth is presented here in a new 4K digital restoration, supervised and approved by director Jonathan Glazer. The film employs a somewhat cool colour palette, feeling deliberately washed out and wintry. This really comes to the fore in this edition, which is rich in tonal depth while remaining true to Glazer’s steely vision. The stark whites of the snow and the deep green wallpaper of Anna’s mother’s apartment linger in the memory; meanwhile, the natural, atmospheric film grain enhances the overall dreamlike tone. Alexandre Desplat’s wonderful, memorable score sounds excellent through this new 5.1 surround DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack. Dialogue is consistently clear and, all in all, it’s a very well-balanced sound mix.

director: Jonathan Glazer.

writers: Jean-Claude Carrière, Milo Addica & Jonathan Glazer.

starring: Nicole Kidman, Lauren Bacall, Cameron Bright, Danny Huston, Arliss Howard, Peter Stormare, Ted Levine & Anne Heche.