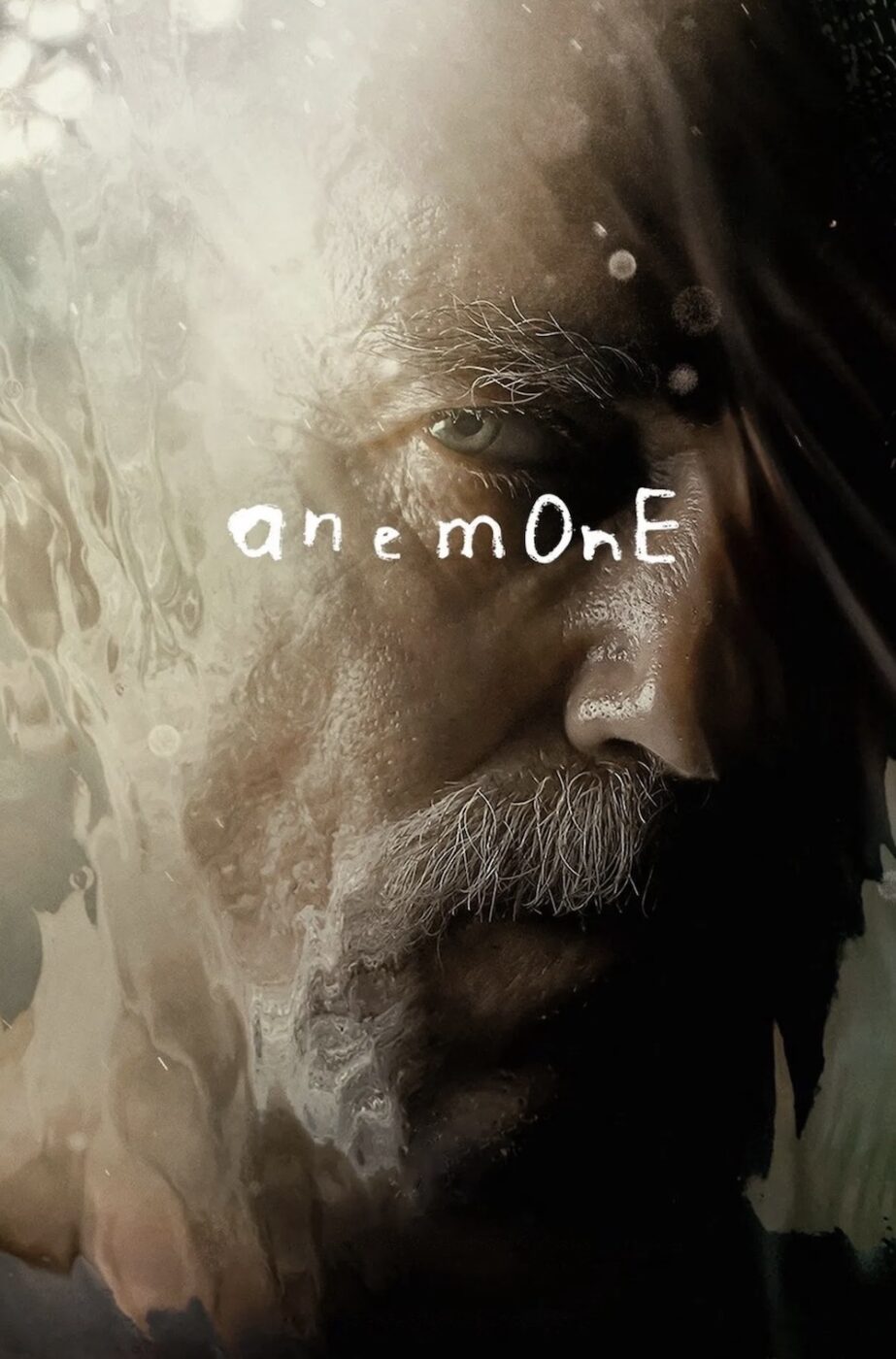

ANEMONE (2025)

In Northern England, a man heads out on a journey into the woods to reconnect with the estranged hermit brother with whom he shared a complicated past...

In Northern England, a man heads out on a journey into the woods to reconnect with the estranged hermit brother with whom he shared a complicated past...

Much like how stories from several cultures’ earlier epochs were presented, the opening for Ronan Day-Lewis’ debut film, Anemone, is presented in the form of a scroll, slowly and continuously rolling outwards, unveiling horrific images that are separate but connected all the same. Images of Irish civilians holding up their country’s flag as they’re shot down by military personnel; the British flag floating above an earthen mound set ablaze; a pub completely consumed by fire born from man’s bombastic ingenuity; and an endless sea of flame dominating the entirety of the page’s verticality.

These images reflect the dissonance of war. Suffering obliterates the ethos that once existed, as the souls of the innocent are reaped while brick and mortar are turned to ruin. For what? Resources? Power? Perhaps there was a divergence in ideology within a particular school of thought? This war, drawn by what I presume is the embodiment of collective innocence based on its non-academic and unrestrained artistic presentation, depicts a moment in Irish history that is known by a few names, such as the Northern Ireland Conflict, or the Troubles.

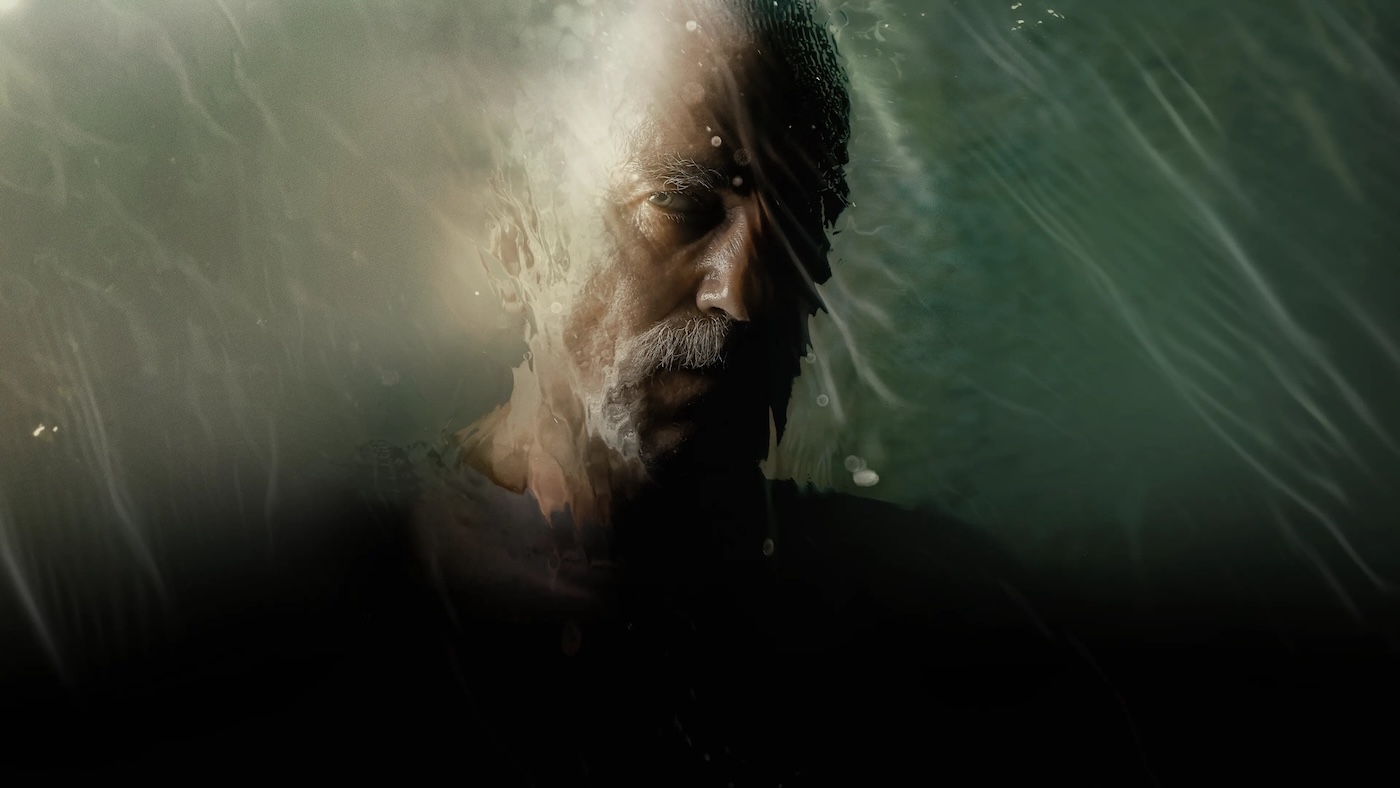

What subsequently follows is wind sweeping across a field of long, luscious blades of chromatic green, as though the wind were fingers gently combing through one’s hair. It then cuts to an overhead view of the same winds moving between trees, causing every intact branch to dance along the gale gracefully—a blanket ballet of greenery; it’s as though the trees are breathing. Life flows through these woods in perfect harmony, creating a stark contrast to the film’s opening. This serene atmosphere guides the viewer towards the film’s protagonist, Ray Stoker (Daniel Day-Lewis), and these sequences of images are stitched together in a manner that speaks a lot about him without having to say anything at all.

Anemone is a fusion of art-house filmmaking and traditional filmmaking practices associated with dramatic conveyance. Its avant-garde elements are used to explore the film’s lore and the psychological and emotional thematic wealth that stems from it, which, in conjunction with the rest of the film, gives Anemone some elements of romanticism and surrealism, though less regarding the presence of the latter. The title of the film is named after the flower, one that is delicate in nature. Anemones close their petals during the twilight and bloom again during the dawn, making them a symbol of anticipation in some cultures, though the flower is seen differently depending on the culture, ideology, or person.

The Ancient Greeks saw it as a symbol of the fleeting nature of love and how fragile life can be. The Victorian era saw it as a symbol of sorrow due to how delicate the flower’s petals are, which are usually blown away by the gentle touch of a passing breeze. The Chinese saw the anemone as a symbol of hope, resilience, and renewal due to the flower’s blooming in late autumn, defying the onset of winter. Those who refer to themselves as ‘spiritual’ view the anemone as having properties that facilitate the process of healing and self-enlightenment. The many ways in which one views this flower, whether by individual colour or lack thereof, or as a flower itself, culminate as the thematic identity for the film, one of fragility, absurdity, healing, and renewal.

It’s from this point that Ronan presents Ray post-Troubles, years after the fact, as his brother Jem Stoker (Sean Bean) has come for a visit to his abode. Conversations between the two show Ray’s instability. He is quick to anger and physical aggression, finds any opening in conversation to instigate one based on what they’re saying, doesn’t shower or change his clothes often, and will speak of stories of the past that flirt with the fine line between sanity and lunacy.

Ronan’s avant-garde approach in thematic evocation is what reveals the intent of Jem’s visit, and that begins to unravel early on. We’re given glimpses of images that comprise something that has been haunting Ray from his past, such as a female spectre floating above Ray’s bed during Jem’s first night there. These images used by Ronan connect to the home life of Ray’s wife, Nessa (Samantha Morton), and their son, Brian (Samuel Bottomley).

It becomes evident early on that after the war, Ray left his wife and son to exile himself into the wilderness, but why? Was it for self-healing and enlightenment? Was returning home after the war too overwhelming, prompting him to alter his environment for the sake of emotional and psychological stability? The reasons are unclear at first, but they slowly blossom with time, like the anemone. What is clear at this point is that Ray’s decision to remove himself from the world has affected his family, including his son.

Brian is an extremely troubled youth, 18 years old, and, like his father, he is prone to anger and physical aggression. Early on, he speaks of a physical altercation with someone for little to no reason—his scabbed and wounded knuckles act as the proof. He also suffers from the eternal conflict of not knowing who his father is: the fact that his father is alive and living out in the woods somewhere, refusing to visit them and ignoring the letters Nessa has sent; and the fact that his uncle Jem has adopted the role of husband and father by proxy, even though this isn’t sufficient enough for him to calm his internal burden.

Through the use of avant-garde and traditional filmmaking practices, Anemone blossoms into something I found cinematically beautiful, albeit a little rough. Its cinematography and editing are at times creative and nearly impeccable; however, there were some notable hiccups in both areas that were jarring and felt unnecessary during both of my viewings of the film. There are far too many zooms, some oddly abrupt cuts, and one or two smaller-scale build-ups to a single word before the scene’s end. Although, the latter was possibly approached this way to emulate the awkwardness and difficulty one may have in starting a conversation with one that they’re bound to by blood and haven’t seen for a long period of time, making it less of a blemish than I originally thought during my first viewing.

Its narrative premise isn’t original by any means, but its story is compelling enough and well-written. I’m not one to proclaim that every film that is made should aim to reinvent the wheel. I find tight writing to be of great value, as familiar stories can still be compelling if they’re written and presented well. Look no further than the Phillipou brothers’ film Talk to Me (2022)—an example I always use when discussing my views on this particular talking point within the medium.

Anemone’s reliance on the avant-garde goes a little heavy at first, but later simmers down, and it then uses its thematic evocation as a means to accent its emotional and psychological meat while the familial dramatics take centre stage. I personally love the imagery used for the psychological portions of the film, especially towards the latter half. They’re subtle yet obvious if you can recognise how they’re used or completely foreign, as their design comes from the paintings of Ronan Day-Lewis, making their representation ambiguous and up to the viewer to give meaning.

Lastly, the proficiency of its cast is first-class. Would it surprise anyone if I stated that Daniel Day-Lewis’s acting is of the same proficiency as where he left it, circa 2017, with Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread (2017)? No. To quote Leonardo DiCaprio:

“…there’s method acting, and then there’s Daniel Day-Lewis.”

It should be no surprise that he plays someone mentally askew after facing such horrors. He, once again, melts into the character he plays and convinces me that he no longer exists. There’s nothing else to talk about there.

Sean Bean does a great job as well. His ability to play off Daniel’s performance genuinely makes me feel like I’m watching an actual familial relationship. Even Samantha Morton and Samuel Bottomley do a great job with their performances as mother and son, though I do always find it a bit unconvincing when someone in their mid-twenties plays someone in their late teens.

There’s a lot to gnaw on with Anemone, yet despite its thematic weight, it flows in the same manner as the winds did during the introduction of the film, like fingers gliding through one’s hair or dancers of gale and greenery. Its presentation of a chapter in Ray’s life is reminiscent of the blooming cycle of the anemone—beginning enclosed, seeing glimpses of its essence between its petals while it slowly opens, then when it blossoms open, it reveals its true essence, then retracts its petals again, awaiting to open for the next cycle.

Anemone is a strong debut by ‘freshman’ filmmaker Ronan Day-Lewis. Sure, it’s a bit rough around the edges, but its synthesis of captivating dramatics and mesmeric visuals washed over me, consuming me and placing me into the film’s ether, its mood, its renewal, and its bloom, like art is supposed to do. I loved Anemone, and I look forward to future work from Ronan.

UK • USA | 2025 | 125 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Ronan Day-Lewis.

writers: Ronan Day-Lewis & Daniel Day-Lewis.

starring: Daniel Day-Lewis, Sean Bean, Samantha Morton, Samuel Bottomley & Safia Oakley-Green.