CAROUSEL (1956)

15 years after his death, a carousel barker is granted permission to return to Earth for one day to make amends to his widow and their daughter.

15 years after his death, a carousel barker is granted permission to return to Earth for one day to make amends to his widow and their daughter.

What do you think of when the words “classic musical” come to mind? Whatever it is, it’s probably not spousal abuse, economic exploitation, or gambling and alcohol addiction. Yet, that’s exactly what Carousel is. It’s likely the reason this was my least favourite Rodgers and Hammerstein film as a child. Despite the beautiful music, the storyline was one my seven-year-old brain couldn’t quite grasp. So, while State Fair (1945), Oklahoma! (1955), and The Sound of Music (1965) were played on a loop in our house, Carousel stood on the shelf untouched—save for the one time my mother took it down to watch it with us.

I didn’t see it again until a particularly dark period in my late-twenties. By then, looking through adult eyes, I could see the true genius that had eluded me as a child. This was the first musical to teach me a lesson I desperately needed: not all stories have the happy endings we expect, but we’ll make it through them anyway.

Though Carousel isn’t technically the first musical drama (that honour goes to another Oscar Hammerstein-penned show, Show Boat), there was enough of a gap between the two that, to many, it felt like the first time a musical had tackled truly dark themes.

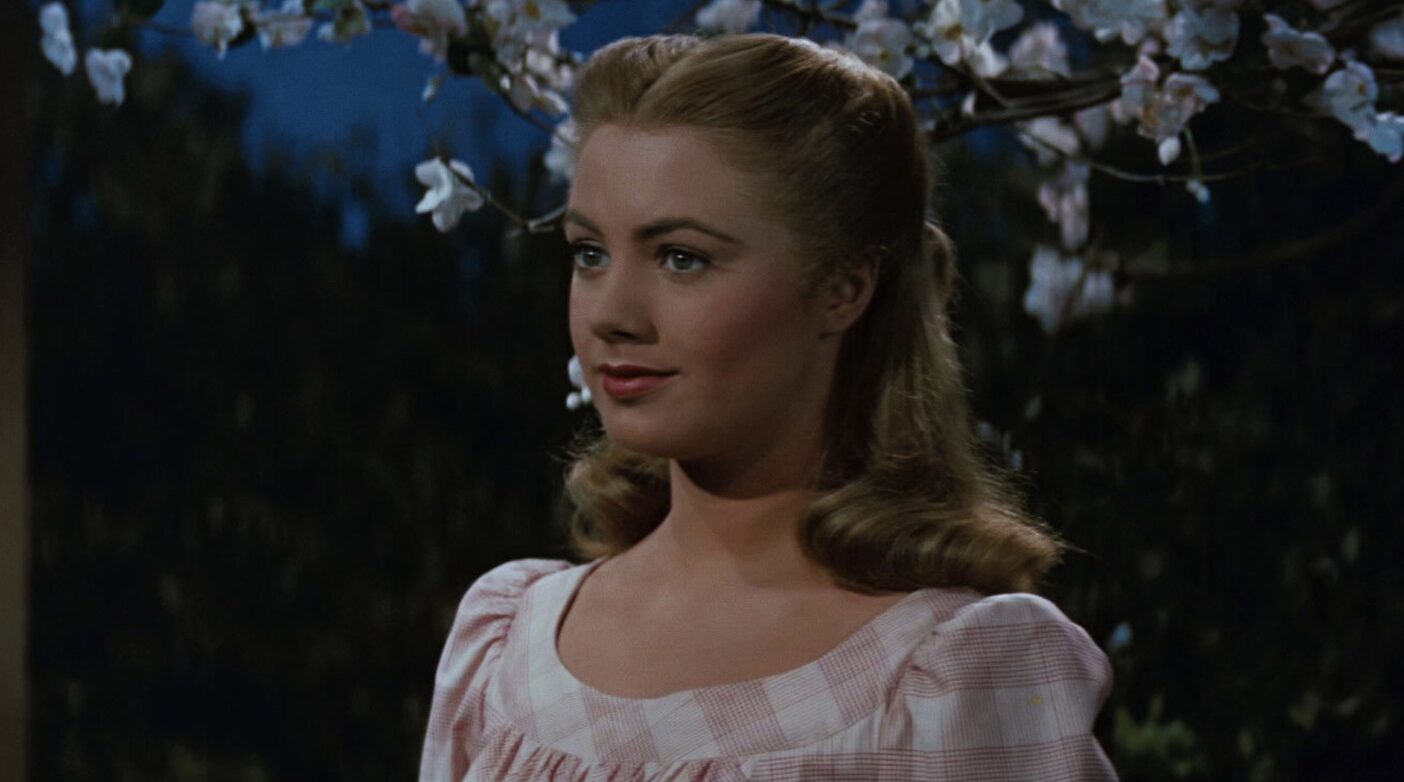

The film opens with Billy Bigelow (Gordon MacRae) waiting at the back door to heaven as he tells the Star Keeper how he came to be there. Most of the story takes place in Billy’s flashback to late 19th-century Maine, where he worked as a carousel barker and fell in love with Julie Jordan (Shirley Jones), a young woman from a nearby mill. When their romance causes both to lose their jobs, they marry quietly. Julie begins working for her cousin, Nettie, at her inn, where the couple also lives. Though it’s clear the pair have struggled since their wedding, their financial problems become more stark when Julie reveals she’s pregnant. Billy vows to get money for his child, by any means necessary.

As Billy ends up at heaven’s door, most readers can guess where this “money at all costs” mentality leads. It involves an attempted robbery orchestrated by Billy’s manipulative, ne’er-do-well friend, Jigger (Cameron Mitchell), and a tragic end for Billy. In more modern fare, that might have been the conclusion; indeed, it was nearly the end of the Hungarian play, Liliom, on which the musical was based. But Hammerstein wanted to leave his audience on a more hopeful note. Billy is allowed to return to Earth for one day to make amends to his wife and daughter, Louise (Susan Luckey).

While I’ve little fear of “spoilers” for a movie turning 75 this year, I’m still loath to give away the bittersweet ending. The film’s hopeful resolution, set to the soaring chorus of “You’ll Never Walk Alone”, remains truly breathtaking.

Though Carousel is darker, dealing with class struggle and addiction, audiences and critics often note the similarities between this and Rodgers and Hammerstein’s first outing, Oklahoma!. Most notably, both films share the same stars: Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones.

Interestingly, MacRae wasn’t the first choice for Billy Bigelow. Frank Sinatra was originally cast and even recorded the entire soundtrack. Though an official reason for his withdrawal was never given, two theories persist. The first is that when Sinatra heard each scene would be filmed twice—once for regular CinemaScope and once for the new CinemaScope 55—he refused, famous for wanting to get everything right in one take. The more intriguing theory, posited by Shirley Jones in her memoirs, suggests Sinatra backed out because his wife, Ava Gardner, threatened infidelity if he didn’t accompany her to the location shoot for her film, The Barefoot Contessa (1954).

Though some speculate Sinatra might have brought more grit to the role, I believe the film is better for his exit. Carousel was written for a full, operatic baritone. I’ve heard Sinatra’s take on “If I Loved You”; while it’s smooth and “pretty”, it lacks the gravitas of MacRae’s sound. While MacRae seems less at home as the street-wise Billy than he did as the charming Curly in Oklahoma!, his vocals are stunning enough to excuse a hint of self-consciousness.

Shirley Jones, meanwhile, seems more at home as Julie Jordan than she did as the flighty Laurey. She handles the serious moments with a maturity and strength of character that shine through. Given her autobiography, it seems Julie Jordan was closer to the real Shirley Jones than the innocent ingenues of typical musical comedies.

While the leads stand the test of time, the supporting cast is a mixed bag. Despite the talk of him being a contemporary of Marlon Brando, I’ve never been a fan of Cameron Mitchell. In every film, he seems determined to “chew the scenery”. The role of Jigger can be multifaceted and funny, but Mitchell’s performance is one-dimensional and often distracts from quieter moments with unnecessary mugging.

By contrast, Claramae Turner is excellent as Cousin Nettie—strong and wise without being overdone. Director Henry King’s decision to shoot on location in Maine was inspired. The choice to focus completely on CinemaScope 55 also paid off; the film stands in stark contrast to the flat-looking colour films of the 1940s. The technique brings out the vibrant colours necessary to balance the tragedy of the tale.

Regarding the story, there are valid contemporary criticisms. Some argue Rodgers and Hammerstein had fallen into a formulaic rhythm. Even if that’s true, the formula here acts as a frame rather than a harness, used to convey a powerful message.

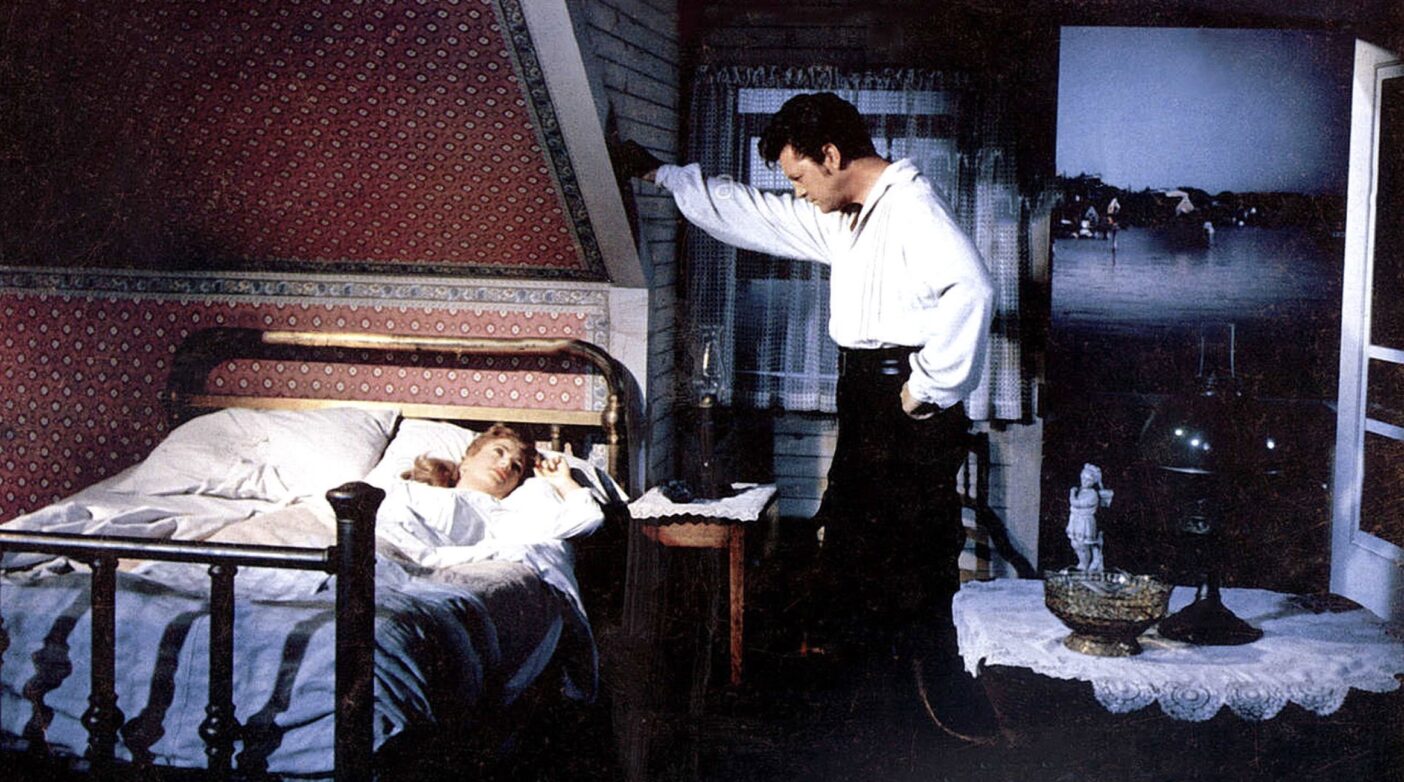

The more significant criticism involves the treatment of domestic abuse. This is what kept me from rewatching the film for years. As a “proto-feminist” teenager, I found the song “What’s the Use of Wond’rin’” infuriating. In it, Julie insists that if you love a man, you stay, regardless of what he does.

Watching it now with adult eyes, I sense the melancholy behind the lyrics. Julie isn’t dispensing wisdom; she’s trying to explain complex, messy emotions. It is possible to love someone who treats you terribly. Hammerstein, aided by Rodgers’ music, tells us what we already know: Julie should leave. But through these lyrics, she explains why she stays:

Common sense may tell you

That the endin’ will be sad

And now’s the time to break and run away

But what’s the use of wond’rin’

If the endin’ will be sad?

He’s your feller and you love him.

By making Billy abusive but not a “monster”, Hammerstein tells a human story. Most people are a mix of good and bad. That’s what makes Carousel timeless. Its characters are human, doing their best with the circumstances they’ve been handed. I might not have understood that at seven, but I certainly do now.

USA | 1956 | 128 MINUTES | 2.55:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Henry King.

writers: Phoebe Ephron & Henry Ephron (based on the 1945 musical by Richard Rodgers & Oscar Hammerstein II Liliom, itself based on the 1909 play by Ferenc Molnár).

starring: Gordon MacRae, Shirley Jones, Cameron Mitchell, Barbara Ruick, Claramae Turner, Robert Rounseville, Gene Lockhart, Audrey Christie, Susan Luckey, William LeMassena, John Dehner & Jacques d’Amboise.