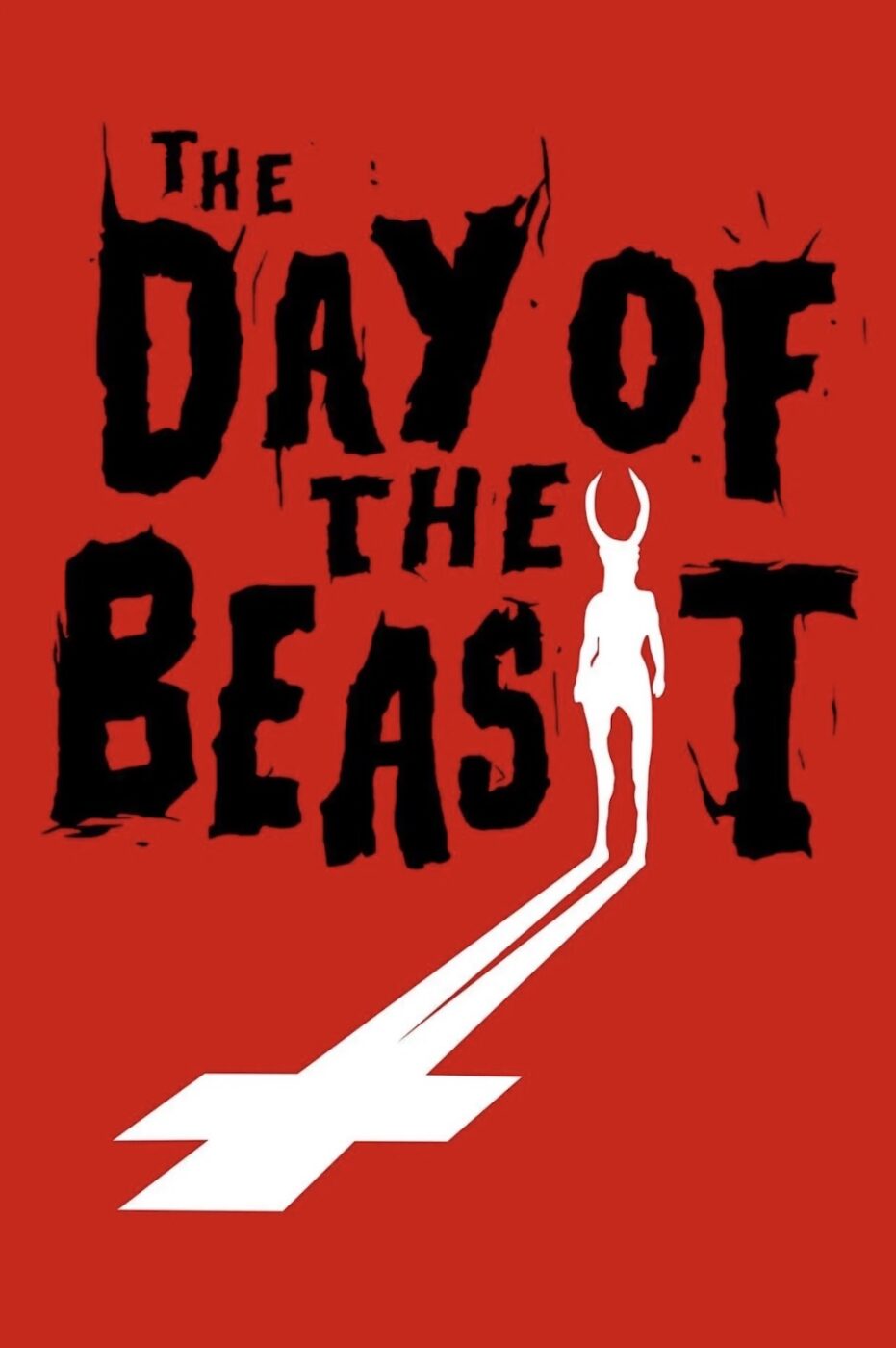

THE DAY OF THE BEAST (1995)

Bent on committing as many sins as possible to avert the birth of the beast, a Catholic priest teams up with a Black Metal aficionado and an Italian connoisseur of the occult...

Bent on committing as many sins as possible to avert the birth of the beast, a Catholic priest teams up with a Black Metal aficionado and an Italian connoisseur of the occult...

There are those who say Halloween is the new Christmas, while others claim it’s the other way around. Either way, Álex de la Iglesia’s diabolically dark horror-comedy, The Day of the Beast / El día de la bestia, makes for perfect seasonal viewing. After all, spooky Yuletide tales have been a tradition since the days of Charles Dickens. While it has been derided as blasphemous by some, its central narrative encompasses the same hope of peace on Earth and goodwill to all.And, although the action takes place over an ill-fated Christmas Eve, its atmosphere couldn’t be more Halloween.

The opening gambit is a real attention-grabber. It has enigma, intrigue, and shock value. Padre Ángel (Álex Angulo) kneels before an altar and its huge, monolithic cross alongside the Sacerdote (Saturnino García), a fellow priest. There’s some impressive production design right there from José Luis Arrizabalaga and his team. Ángel, speaking in hushed tones, explains that he’s about to set out and “do all the evil I can,” because he’s finally “cracked the code.” The more pertinent details are drowned out by church bells, and yet the Sacerdote cautions that they may be overheard, even in the church. The plan is to be as vile and sinful as possible in the remaining short time before the foretold coming of the Antichrist on Christmas morning. Thus, convincing the dark powers that the curate is evil enough to be present at the birth and get the chance to avert the Apocalypse by slaying the Son of Satan. As they’re leaving, Padre Ángel drops his notes as the massive cross topples, narrowly missing him but flattening his compadre. The scene efficiently establishes the film’s distinctive blend of gothic horror and grim humour.

More often than not, I find horror-comedies tend to be too nasty to be funny or too frivolous to be scary. However, apart from perhaps Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead (1981), there are very few films that strike the balance as perfectly as The Day of the Beast. For those not easily offended, there are several laugh-out-loud moments and plenty of guilty giggles. Yet there are scenes of shocking violence, and the horror element is truly disturbing, yet profoundly affecting on an unexpectedly deep emotional level. A film full of surprises with a standout script penned by the director with regular writing partner, Jorge Guerricaechevarría.

Álex de la Iglesia’s flair for visual storytelling harks back to his involvement with comics and critique for the indie fanzine, No, el Fanzine Maldito / No, The Cursed Fanzine. In the early nineties he shot his first short films, which caught the attention of Spain’s rising cinematic star, Pedro Almodóvar, whose production company helped Álex de la Iglesia finance his first feature: Mutant Action / Acción Mutante (1993)—a masterclass in orchestrated chaos with a brash indie punk aesthetic. The audacious, all-action science-fiction satire was a surprise underground success. It demonstrated that Álex de la Iglesia was not risk-averse and happy to push the envelope in several directions at once. When it received six nominations for the Goya Awards, Spain’s most prestigious film accolades, it also proved his films had mainstream appeal. It won three of them: ‘Special Effects’, ‘Hair and Makeup’, and ‘Production Supervision’.

Padre Ángel roams the streets of Madrid on his spree of evildoing, robbing from buskers, pushing a mime artist off the railings of a metro station, taking the wallet of a dying man and, instead of administering the Last Rites, cursing him to rot in hell. He soon realises that his propensity for evil is limited and so he seeks inspiration in a record shop that specialises in Satanic Death Metal. After sharing some lame tips on how to meet Satan and recommending a local venue, the metalhead proprietor, José María (Santiago Segura) is intrigued by Padre Ángel. He recommends lodgings at the hostel his overbearing mother (Terele Pávez) runs and becomes his sidekick on the quest. Together they kidnap television psychic Cavan (Armando De Razza) and force him to help them invoke the Devil.

Though most of the secondary characters are painted with big, brash strokes, the principal cast are all pitch-perfect. Newcomer, Santiago Segura won the Goya for ‘Best New Actor’ for his surprisingly subtle and ultimately humane portrayal of José María. In all, the film was nominated for no less than 14 Goyas and won six, including ‘Best Director’. Arturo ‘Biafra’ García and José Luis Arrizabalaga took home ‘Best Art Direction’ for the excellent production design. The SFX team of Juan Tomicic, Manuel Horrillo, Reyes Abades nabbed ‘Best Special Effects’ and the film also won ‘Best Makeup and Hair’, and ‘Best Sound’. It’s great to see Spain’s film industry showing such respect for a genre movie.

For me, the standout scene that turns everything that’s gone before on its head is when the unlikely trio perform the summoning ritual so Padre Ángel can seal his pact with the Devil. Surprisingly, it’s successful and Baphomet shows up incarnate. This is my all-time favourite screen depiction of ‘the horned one’, easily besting the goat-guy sat on a rock in The Devil Rides Out (1968). The moment this otherworldly black goat suddenly stands erect is so surprising and suitably creepy. Its unexpectedly carnivorous grin straddles mirth and malice as it sees through their flimsy ploy to fake being evil…

The whole look of the beast is clearly inspired by the dark and grotesque paintings by Spanish Baroque painter Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, more usually referred to simply as Goya—thus commemorated in the name of the Spanish film awards. He purchased a two-storey house in the countryside near Madrid and over the first quarter of the 19th century he painted a series of sinister murals now known as ‘The Black Paintings’.

There’s a theory that these paintings, in which strange scenes from mythology and folklore loom out of black backgrounds, were presented by lamplight, revealing the phantasmagoria in sequence, in the style of a magic lantern show mixed with a ghost walk. This could also be interpreted as a very early version of cinema! The two most famous panels are the images known as ‘Saturn Devouring His Son,’ a gory depiction of the mad god, and ‘The Great He-goat of the Witches’ Sabbath / El Gran Cabrón Aquelarre.’ The latter is a wall-sized painting that melds humour with horror, featuring the titular horned one and his congregation of grotesquely caricatured acolytes—its aspect ratio even presages Cinemascope. Acknowledging the influence of Goya, possibly Spain’s most important artist, helps one to understand both the challengingly comedic and politically satirical aspects of The Day of the Beast.

Of course, there are drugs involved in their wonderfully clichéd ritual but, whether it’s real or not, they all see the same things here. Pointing out this dangerous parallel between hallucinatory mental illness and zealous blind faith is a confident and courageous step for a director operating in Spain’s staunchly Catholic climate. Though Luis Buñuel prepared the ground with his many iconoclastic movies, taunting the Church and irrational dogma since the 1960s—perhaps most successfully with his humorous though intentionally contentious script for The Milky Way (1969). I am reminded of Buñuel’s famous comment, “a religious education and Surrealism have marked me for life. Thank God I’m an atheist,” and as with most Buñuel movies, I wouldn’t recommend The Day of the Beast to anyone lacking an open mind and a sense of humour.

The premise of a good man doing evil things propels us through the first half apace. Everything is full of energy. The irreverent dialogue is essentially expositional, yet witty and cleverly naturalistic. There’s lots of high-impact action, notably one scene in which a shotgun-wielding woman falls to her death down a stairwell, hitting every banister on the way down. It’s as bone-crunchingly frightful as something from a Dario Argento classic. Never a dull moment. Though it does appear to lose momentum at the close of the second act when Padre Ángel feels lost, abandoned, and believes he’s failed to save the world from its doom.

It’s then that Cavan the chat show charlatan, convinced by their summoning ritual, suddenly becomes a serious occult scholar. His visual analysis of several facsimiles of Satanic pacts from the past convinces him that the Sigilo de Satán was always written by the same hand, sometimes centuries apart. He also deciphers a key clue hidden in its design that will lead them to the location of the Antichrist’s birth. As the finale unravels, the narrative veers away from irony and absurdity into darkness, delivering a profound philosophical message with a very clever twist.

The climactic scenes play out high in Madrid’s Gate of Europe towers which were still under construction at the time, to be completed the following year in 1996. Without giving too much away, the final revelation is that the Antichrist will not be a baby born of woman but will come into our world through the intolerance and hatred of violent men. Nothing mystical, simply the rise of right-leaning, neo-Nazi ideologies that seek to dehumanise others simply due to their colour, creed, gender, lifestyle, or any opposing ideology. It’s worth remembering that Álex de la Iglesia grew up in the final years of the fascist Franco Regime and the era of ETA, a murderous paramilitary organisation of Basque separatists. Rather terrifyingly, news reports of this kind of irrational intolerance, expressed through violence, seem to be proliferating even today in supposedly civilised democratic nations.

The apocalypse is still pending.

SPAIN • ITALY | 1995 | 99 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | SPANISH • ITALIAN

director: Álex de la Iglesia.

writers: Álex de la Iglesia & Jorge Guerricaechevarría.

starring: Álex Angulo, Santiago Segura, Armando De Razza, Maria Grazia Cucinotta, Nathalie Seseña & Terele Pávez.