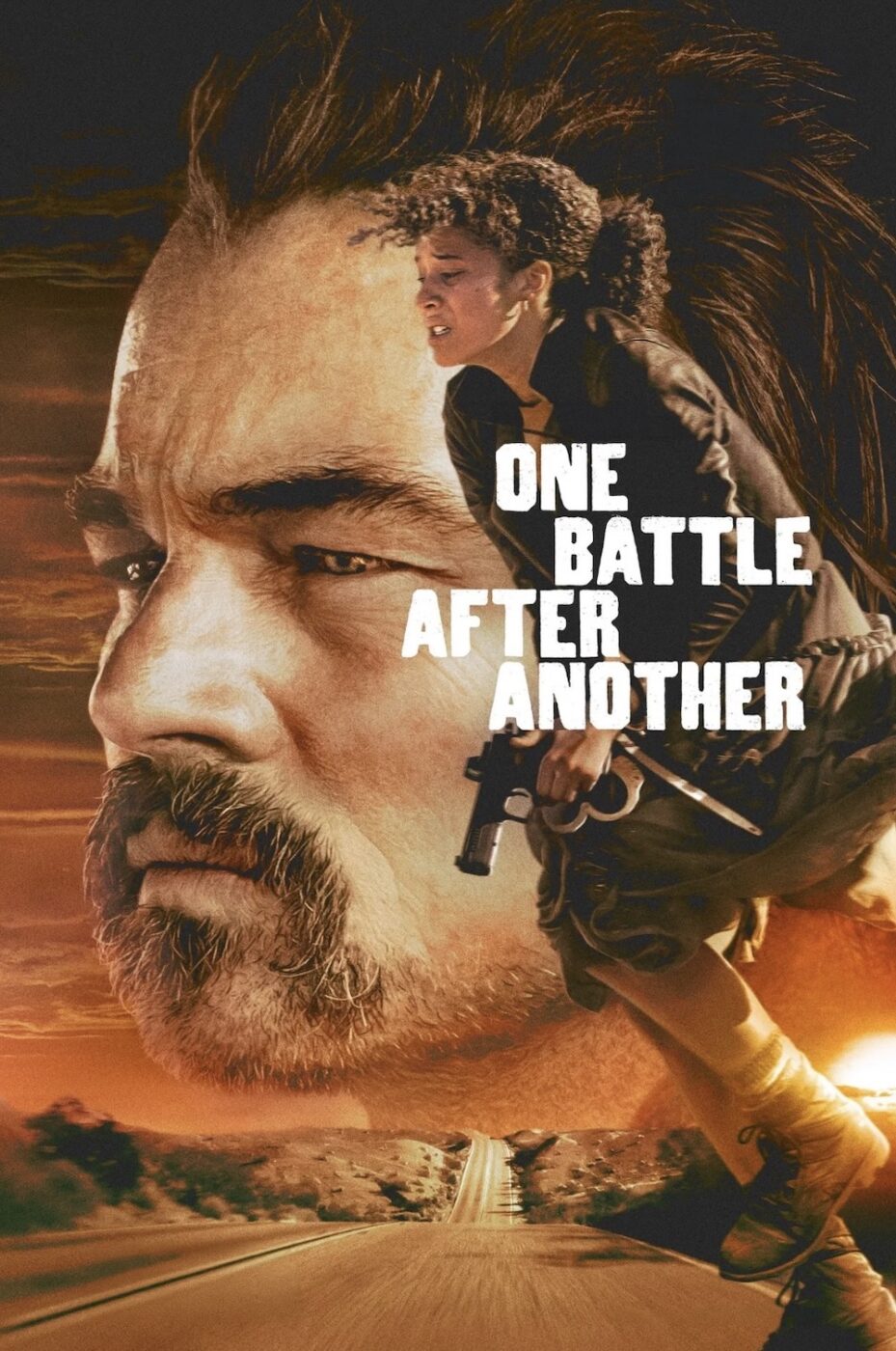

ONE BATTLE AFTER ANOTHER (2025)

When their evil enemy resurfaces after 16 years, a group of ex-revolutionaries reunite to rescue one of their own's daughter.

When their evil enemy resurfaces after 16 years, a group of ex-revolutionaries reunite to rescue one of their own's daughter.

Paul Thomas Anderson once again weaves a thrilling narrative of mesmeric proportions and cinematic proficiency with his most recent film, One Battle After Another, although this time around he focuses on a setting and conflict he has never covered before, both thematically and narratively—a world of American political extremism and the behaviour that exists because of its ethos. Though this film is based on Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 novel Vineland, it concerns itself with the American nationalist ethos of the now, one of authoritarianism, racial sterilisation, and white nationalism, though unlike its source material, no one specific politician or military figure is mentioned.

Oppressive governmental forces have slowly begun to siphon the many nuances of its populace’s land-given rights here in the states, whether they’re legal citizens or those working towards becoming one. The First Amendment has especially been meeting the insatiable appetite of the politically elite and their prominent physical extensions, whether by occupational practice or by public sermons disguised as discourse, congregating together with their proboscis and sucking the sanguine of liberty right from our veins.

Pat Cahoun(Leonardo DiCaprio), also known as ‘The Rocket Man’ due to his proficiency in explosives, and Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor) are part of a liberal revolutionist group known as The French 75, who are in a constant battle against the oppressive regime. Actions are discussed, planned, executed, and swiftly celebrated, only to continue this ad nauseam. This cyclical process is never-ending. As long as there’s any form of control governing people of a socially defined region, then there will always be corruption—man’s unconscious does not hunger for stability and equality.

This relationship between oppressor and liberator is perfectly illustrated by the sexual dynamic between Pat, Perfidia, and Col. Steven J. Lockjaw (Sean Penn). Perfidia’s characterisation is centred on immense political fervour. She feels exhilaration through the process of the group’s missions, so much so that said exhilaration becomes an aphrodisiac. Both in planning and execution, Perfidia wants to engage in sexual activity with Pat, even in the very moment of explosives going off—her libido is off the charts.

In their moments of intimacy, although she’s the initiator, there’s a level of equality between them. One excites the other and vice versa—actions indicative of how collective passion towards X can initiate the execution of actions and continuously facilitate their ever-increasing reach. Perfidia also delves into the realm of adultery, as she involves herself sexually with Col. Lockjaw; however, she’s completely dominant in their intimate waltz, consisting of teasing, edging, sexual humiliation via commands, and the use of physical objects that aren’t predicated on pleasure—a clear sign of actions executed by liberators as a whole and the pleasure they receive from each blow they deal to their opposition.

Col. Lockjaw feels physical fulfilment from these secret sexual escapades as well, only to desire more from Perfidia, but through a forceful role reversal, as generally his next course of politically driven actions fuels the liberator’s desire to continue to strike back at oppression. Like Batman and The Joker, political oppression and desires of liberation are destined to be together forever. This element of fatalism is highlighted within the early portions of One Battle After Another, as it consists of the progress in the relationships between Pat and Perfidia, Perfidia and Col. Lockjaw, and the progression of the French 75’s efforts towards fighting oppression via a 35-minute montage.

In most cases, I dislike the use of a montage to progress a film’s narrative, themes, characterisations, and character dynamics, as I find it to be lazy. Most filmmakers rely on it as a crutch to cover a long period of temporal occurrences without having to dedicate the appropriate time to properly flesh it out practically; however, given Anderson’s proficiency as a filmmaker and how meticulous he is in crafting each element of the medium, One Battle After Another’s montage is one of the best I’ve witnessed.

Unlike traditional montages, the one employed in this film isn’t a continuous stream of highly summarised events within the span of a few short minutes; rather, it draws out each event as much as possible while the meat attached to the bone is trimmed off, creating a lean sequence of events that spans over two points in time. Regardless of Anderson’s approach in crafting the montage in this film and me proclaiming it to be one of the best I’ve seen, I still dislike it.

Firstly, I prefer montages to cover secondary elements of a film’s narrative, as it doesn’t hinder the main meat of the film, like the montage Scorsese employs in Raging Bull (1980), where he uses the montage to cover a significant moment in Jake LaMotta’s life that isn’t related to his passion for boxing: his wedding, honeymoon, and post-matrimony days of his newly evolved relationship with a minor. Secondly, Anderson is a filmmaker that flourishes in controlled chaos and not in guerrilla smartphone filmmaking that compromises the flow of continuity. The first 35 minutes of One Battle After Another felt its length to me, which juxtaposes how the rest of the 127 minutes of film felt.

I had difficulty fully engaging in the events, progression, and fall of certain characters, because all who weren’t Pat, Perfidia, and Col. Lockjaw had no time to exist, let alone breathe, in these sequences. How am I supposed to become emotionally invested in side characters if the bulk of their time is within this montage? Luckily, One Battle After Another takes off after the dust settles, though I would have much preferred if the first 35 minutes had played out more traditionally.

Was Anderson scared of another entry having a run time of over 180 minutes? Possibly, but I hate sacrifices like this, and when a film’s run time comes up in conversation, I usually use the following quote from another favourite filmmaker of mine:

“Who gives a fucking shit how long a scene is!?”—David Lynch

Seriously. Why does it matter? If a bottle of wine requires a specific length of time in a decanter to properly aerate and be ready for enjoyment, then you aerate as such. If a baking recipe requires a specific length of time to prepare in the oven, you bake it for that long. If a scene in a film needs to be a specific length to maintain its level of immersion, quality, and artistic integrity for the film to work, even if it lengthens the overall run time, you do it. Art is never fully realised if compromises are made—this I learned as a painter.

To contend against my own disdain towards montages and Anderson’s failed, though skilfully constructed, montage in One Battle After Another, I can see a potential reasoning as to why Anderson went this route when crafting the film: it facilitates the film’s thematic cyclical relationship between oppressor and liberator and creates the feelings one would have when in a collective of shared passion towards something. When one is in a collective of their desires and they’re executing actions and events that they so passionately want to do, life just passes on by. So much is done, and one is living their best, most exciting life, yet it’s gone before one knows it—life flows like a river and occurs like a blip.

Then, before you know it, without warning, without rhyme or reason, time just comes to a halt, fecal matter hits the fan, and undesirable outcomes become reality. Then, the dust settles, and the preceding events become a blur until life once again comes to an apex. It’s here where the montage ends and the film starts to flow at a pace more aligned with Anderson’s skillset—a point in time that is 16 years after the fact. So much has occurred within that time, but most of it’s a blur to Pat. Now, he’s a shell of his former self, indulging in vices that aren’t conducive towards maintaining one’s resolve.

Anderson’s montage was done to set up for what he wants to focus on, and it most certainly pays off, so despite my contempt towards most montages, I’m not too put off by its inclusion in this film, even though it hinders some character interactions and occurrences later on in the film. If anything, I respect its inclusion, as it shows that Anderson is confident in showing a practice he normally doesn’t employ.

That’s my only criticism towards Anderson’s One Battle After Another; the rest of the film is cinematic perfection. It’s a cinematic tapestry of genres, composed of elements of dark, satirical, and absurdist comedy; absurdism; political and familial drama; thriller; action; and what have you. It’s a lot, yet all of these elements meld seamlessly together to create quite the experience.

Anderson brings out a proficiency in Leonardo DiCaprio that I seldom see. DiCaprio is an extroverted actor with a lot of energy, yet he has many roles where his strengths aren’t fully utilised. These roles are more archetypal and symbolic in nature rather than human, which sometimes calls for a more withdrawn performance, both in energy and emotional evocation. In both Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood (2019) and this film, DiCaprio plays a more human role, which utilises his proficiency in drama and comedy and the spirit of his extroverted style. This is by far my favourite DiCaprio role, hands down.

The rest of the performances in this film are worthy of reverence as well, as everyone is firing on all cylinders. Benicio del Toro plays a calm, collected, and rather charming martial arts sensei who owns his own dojo that Willa (Chase Infiniti), Pat’s daughter, grew up taking classes in. Chase Infiniti’s performance as Willa, which happens to be her first major performance, is perfect, as it embodies great levels of strength, courage, independence, and femininity. There’s a sense of charm on the surface that masks an ever-burning will and resolve in Willa that stands firmly upright and acts as an exemplification of how kin do not follow in the footsteps of their parents.

Then there’s Sean Penn, who disappears into his role. He’s eccentric yet equally militaristic and bloodthirsty. His will and resolve are like a finely sharpened blade that cleaves open everything it disembowels with ease, yet there are these pathetic notes seeping from him. Col. Lockjaw is a snake, slithering into desired situations and out of undesirable ones; he’s willing to do what it takes to meet his goal, no matter how despicable, yet takes offence when his masculinity is threatened outside of the bedroom. I can’t think of a single bad performance in this film. Anderson has a gift for selecting the right actors for roles in his work.

It wouldn’t be a Paul Thomas Anderson film without adept cinematography and editing, and One Battle After Another delivers on this front, too. Every shot, from the first frame to the last, is composed perfectly, down to the smallest detail, evoking a keen sense of balance and allurement.

There’s the shot of the US-Mexico border in the nocturne that stands so monolithic that it engulfs most of the shot, presenting itself on a scale and nature equating to the biblical leviathan, yet the earthen slope that begins to rise on the leftmost part of the shot and comes to an apex on the right is able to create a balance in the frame. Then there’s the shot of Perfidia firing an automatic rifle in an open land while pregnant. Her stomach is exposed with the clip of the rifle touching her baby bump—an immensely powerful symbol of generational upbringing, as Perfidia comes from a long line of revolutionaries, according to Momma Sandrae (Vanessa Ganter) and Grandma Minnie (Starletta DuPois).

There are so many memorable shots to fawn over. There are the long stretches of desert highway, composed of waves of tar through the use of traditional landscape framing and point-of-view perspective; the shots where the burst of fire from an automatic rifle illuminates flesh and steel in chromatic energy within the penumbra as another battle has successfully been won; shots of peaceful protests accented by neon and fluorescent incandescence being smothered by militaristic chemical weaponry and apathy; and tracking shots on open streets and rooftops, as well as static shots of liminal hallways that evoke the chaos and confinement that Pat feels internally and that exists in the ethos due to the overwhelming presence of the regime. I could spend another 5 or so paragraphs drooling over how visually immaculate One Battle After Another is, but I believe I’ve said enough.

Anderson has done it again, though, if you ask me, he rarely misses. Even the films in his filmography that I’m not nearly as enamoured by are still of a level of quality and craftsmanship unlike most of what exists within the ocean of cinema. His proficiency in this medium has set a standard within filmmaking here in the states that most filmmakers and proclaimed greats in the contemporary cinematic climate will never be able to reach. One Battle After Another is a powerful, bombastic, gripping, tightly choreographed and written, action-accented thriller that perfectly captures the politically extreme ethos of American soil and the attitudes and actions of those within it.

It succeeds at what many filmmakers fail at doing when incorporating politics into their world, such as Bong Joon Ho’s Mickey 17 (2024) and James Gunn’s Superman (2025), where not enough time is spent in developing said backdrop to envelop and feel naturally part of its world, causing it to become more of an aesthetic than anything else. It succeeds in obtaining thematic symmetry with its focus on political extremism, whereas someone like Ari Aster nearly obtains it but falls a little short in his recent film Eddington (2025)—a cinematic retrospective of the COVID-19 pandemic. It succeeds in its construction and utilisation of cinematic elements where many filmmakers of today fail, as they rely on stale and sterilised practices that occupy all of the elements of cinema as a crutch to ensure stable ticket sales rather than expanding their knowledge and, in turn, furthering their skill within the medium.

Anderson is one of the best living American filmmakers, arguably the best depending on who you ask. I’m grateful to have met my now close friend during my alternate graduate studies, as if it weren’t for meeting him, there’s a chance I would have never been exposed to his work, even now, as I went to see One Battle After Another knowing it was Anderson’s film. Thank you, Nick, for the recommendation. It has been life-changing.

USA | 2025 | 161 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • SPANISH

director: Paul Thomas Anderson.

writer: Paul Thomas Anderson (based on the novel ‘Vineland’ by Thomas Pynchon.

starring: Leonardo DiCaprio, Sean Penn, Benicio del Toro, Regina Hall, Teyana Taylor & Chase Infiniti.