SOMEWHERE (2010)

After withdrawing to the Chateau Marmont, a passionless Hollywood actor reexamines his life when his 11-year-old daughter surprises him with a visit.

After withdrawing to the Chateau Marmont, a passionless Hollywood actor reexamines his life when his 11-year-old daughter surprises him with a visit.

Outside of his acting duties on-set (which, crucially, we don’t see), the actor protagonist of Sofia Coppola’s Somewhere, Johnny Marco (Stephen Dorff), is quite like a highly expensive, coveted doll. He’s pampered before these shoots begin, peppered with questions far too complex for him to answer by journalists, adored by total strangers that are besotted with celebrity instead of the man standing before them, and ushered about by over-eager PR people whose constant praise is so false that one wonders why they even attempt such a ludicrous performance. When Johnny isn’t performing, he’s depressingly mediocre, something we know from the very outset of the film, since Coppola cleverly gives us no reason to buy into the allure of his celebrity.

As for his personality, this protagonist doesn’t exude (or possess) charm. Celebrity is a strange, cyclical ritual that Johnny keeps being subjected to, pushing him further and further away from anything resembling a normal life and the connections we attempt to forge within it. He’s stuck in an endless loop, suffering at the cost of success. I won’t pretend that there weren’t moments where Johnny’s lifestyle seemed highly desirable, but by the end of the film Coppola has carefully constructed this protagonist’s existence as a glass house that threatens to fall apart at any moment. You know this moment of self-destruction will be shattering, you know that it’s inevitable, and you know that it’s a good thing, too, since it’s the only opportunity he will ever get to break out of this paralysing stasis.

It’s no easy task to get viewers to sympathise with ultra-wealthy figures like Johnny, especially when there’s no obvious tragedy in their lives, with Coppola doggedly committing to depicting the day-to-day life of this famous actor. She manages to do the impossible by ensuring that we never become smitten by Johnny’s fame, allowing for a deceptively rich exploration of who he is. There’s no mystique, only a reality that at first seems too good to be true, but which slowly reveals itself to be so hollow at its core that one can’t help but feel like wanting to offer a hug to Johnny. He’s just cognisant enough to make himself amenable to being ushered from room to room, hotel to hotel, country to country. When he doesn’t have work obligations he can go anywhere he pleases—the ultimate freedom—but it becomes clear that he’s even more trapped than you or I.

Instead of physically drawing Johnny close to us through revealing, intimate close-ups, Coppola opts for a fly-on-the-wall visual approach. It does wonders to highlight the rampant alienation in Johnny’s life, where the divide between him and other people causes him to dissociate from them. We don’t need gaudy parties or outlandish characters to make this clear; instead, Coppola keeps this narrative running on a constant track, an endless, short loop of press obligations, sexual partners, and lonely nights. At his happiest, Johnny is bemused by life, a slight and slightly confused smile appearing on his face as he assesses the everyday madness of his surroundings.

Many directors would see these moments as the ideal time to employ a close-up shot, where there’s no escaping whatever it is that the camera seeks out, like a cluster of DNA trapped underneath a microscope. But by rendering all of Johnny’s reality through wide, medium shots, Coppola is not attempting to be lurid, or even revealing, in these moments. It is not these interactions that are necessarily revealing, but their sameness. It is the routine that is inescapable. The static camera and repetitive shot choices create distance between Johnny and the people he interacts with, while underscoring just how dull life can be when it rests on a hollow core. Coppola may defer to a very obvious metaphor about this protagonist’s life in Somewhere’s opening shot, where Johnny drives in a loop on a race course track, but I can’t think of a more fitting introduction into the life of someone who has fallen victim to a routine that robs them of an identity.

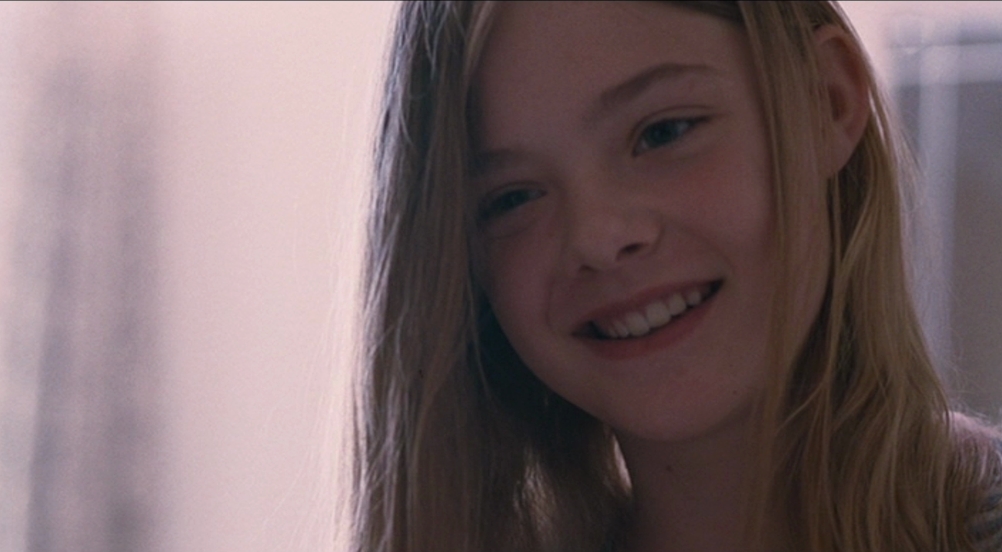

Throughout this 98-minute film, Johnny attends to various publicity requirements for his latest film and spends some time with his 11-year-old daughter Cleo (Elle Fanning), who is also a bit bemused by his lifestyle and the notion that what is strange is simply routine for her father. Fanning provides a wonderfully sensitive child performance, especially in a scene where she seethes with resentment towards her father as they have breakfast with a woman that Johnny slept with the night before. There are times when Fanning makes Cleo seem wise beyond their years in these scenes, but when she laughs she seems like a regular kid, slightly embarrassed of how amused she is by silly comments from Johnny’s childhood friend Sammy (Chris Pontius).

Dorff was thought of early in the writing process of Somewhere for the role of Johnny Marco, with Coppola stating that he had the aura of a ‘bad boy actor’, but also a ‘sweet, sincere side’. What’s interesting is how understated this role is, to such a degree that those would hardly be the first descriptions I would think of in attempting to describe this protagonist. Mostly he’s unremarkable, bemused by other people and haunted by loneliness and disassociation, since the way Johnny’s identity is reflected back at him is such a distortion that it doesn’t seem human.

What’s fascinating about Dorff’s performance is how easily he bears his character’s sorrow. Coppola recognises that an actor who has a boyish look is often utilised for their smouldering good looks and ability to turn up their charm, but it’s the vulnerability and self-pity lurking beneath those qualities that’s usually more intriguing. Dorff isn’t a bad boy here, but he’s seen as one. People view him through a hyper-specific lens before they ever meet him in person, a perspective they aren’t willing to give up without a fight, despite his personality never living up to the hype. It’s an acting masterclass of realistic, grounded sorrow.

It’s only when Cleo arrives that Johnny is able to find a degree of meaning in his life. He has become dulled to the thrills that his lifestyle provides him, but his excitement is renewed by getting to view them through the perspective of someone he loves dearly. Somewhere is a movie that has inevitably garnered detractors – whether that’s movie fans or critics – for not being about anything, or for failing to tell a story or take its characters on a journey. It contains slow, lengthy scenes that mostly exist to explore Johnny’s hollow routine. It’s true that a few of these scenes go on for too long, especially in the first 20 minutes, since it takes time sitting with Johnny’s existence as a whole, rather than just the individual moments themselves, to parse just how exhausting this privileged lifestyle is. It’s only in Cleo’s absence that the film is able to fully unveil its heart, where Johnny’s life suddenly seems colder than it ever was. Without such a consistent way of composing this narrative’s look and its bleak, spare emptiness, the few times where Coppola deviates from this norm wouldn’t be nearly so emotive. A simple zoom out of a father and daughter sunbathing to reveal their surrounding environment is a tender reminder that we are all part of a wider story, something that Johnny is remiss to forget as a celebrity who attracts people into his orbit without doing or saying anything interesting or meaningful.

Somewhere’s last shot is an even greater revelation, tying in superbly to its opening sequence. Strangeness is routine, normalcy is easy to want but difficult to pursue, and the chance to go somewhere, anywhere, is as essential to Johnny as drinking water or breathing. He goes to interesting places and does interesting things all the time, of course, but the drawback is that he cannot escape himself. To get away from this ordered madness and not have that experience be fuelled by loneliness or self-hatred is Johnny’s test to prove that he’s still a human being. It’s an emotionally absorbing pursuit that wouldn’t be nearly so effective if not for Coppola’s crystal clear view of how to illuminate this story, a modern day Jeanne Dielman (1975), with a far more merciful running time. Not every scene is illuminating. Some are even mundane. But Somewhere is always building towards something greater, with an impressively realised vision that never compromises for a single moment.

USA • UK • ITALY • JAPAN • FRANCE | 2010 | 98 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR| ENGLISH

writer & director: Sofia Coppola.

starring: Stephen Dorff, Elle Fanning, Chris Pontius, Michelle Monaghan, Kristina Shannon, Karissa Shannon & Lala Sloatman.