Take 5: Best English-Language Remakes

Some of your favourite films aren’t original pieces of work, but the result of Hollywood studios being so impressed with a foreign movie they decide to make their own version. This has always been a difficult challenge for writers and directors, as it’s hard to catch lightning in a bottle twice, but there are occasions when a clever adaptation can work. And in those instances, a film that’s less accessible (because of low public awareness, or the love-hate relationship with subtitles) can find a wider audience. It also means that the original can receive a boost in popularity, as more discerning audiences seek it out to compare and contrast.

Below, five of our writers choose a film that was either a direct remake of a foreign film, or heavily inspired by one. These are all examples of remakes that work surprisingly well for a different culture, and in some instances surpass their predecessor because any shortcomings can be avoided the second time. Let us know your own favourite English-language remake in the comments below!

Jim Jarmusch once said to “steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination”. In an ideal world, this sentiment would be the basis for remakes, as it highlights the cruciality of returning to age-old stories: that they inspire something entirely new in us. Rather than just take an existing property and slap a new title on it, in the hope audiences will buy into something simply because they recognise it, the best remakes continue an existing conversation—keeping something old alive while adding a new perspective.

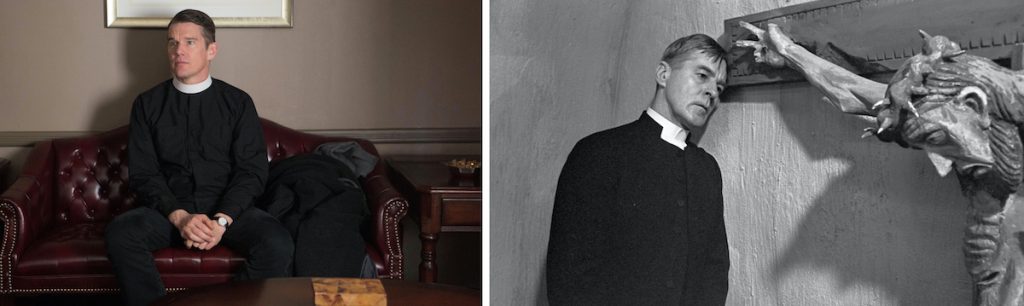

A remake in everything but name, Paul Schrader’s First Reformed follows the template of Ingmar Bergman’s Winter Light, but approaches the same themes from a different perspective. Both films follow pastors (Gunnar Björnstrand in Winter Light, Ethan Hawke in First Reformed) facing a crisis of faith after encountering troubled members of their flock. First Reformed faces existential uncertainties with anxiety, but smartly updates the worries of Winter Light for the 21st-century, with global warming and increasing secularism on the mind of Pastor Toller. In doing so, Schrader transcends the subject of religious anxiety and instead grapples with the shortcomings of faith, and the human desire to believe in something despite losing trust in American institutions.

While Bergman always kept a flicker of hope alive in his films, and faced his worries inwards in quiet contemplation, Schrader’s movie is combustible and terrifying—feeling unhinged and unmoored as it burns a path through its dark night of the soul. That’s what makes it such an effective ‘remake’—it doesn’t comfortably reaffirm what the original film suggest. It’s in dialogue with Bergman’s film but treads where his film didn’t, or couldn’t. Schrader makes both his and Bergman’s works feel vital again.

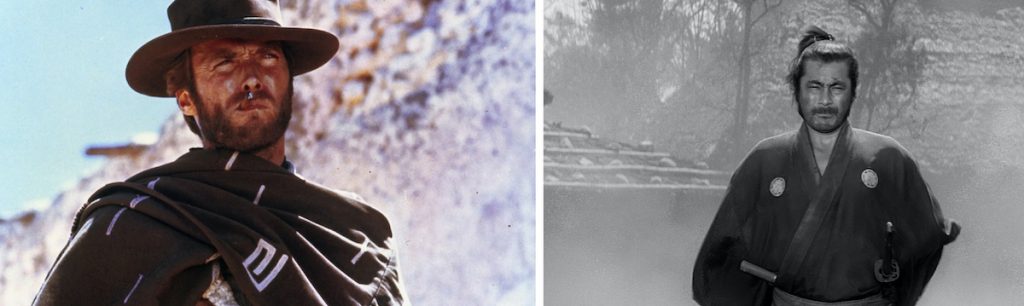

It’s widely accepted that the Spaghetti Western was inspired by Japanese Samurai films, or chanbara. Hollywood directors saw the parallel in their semi-mythic settings and the potential of replacing swordsmen with gunmen, whilst keeping the central narratives intact. The samurai source material has always been superb, but international audience were slow on the uptake and it remained fairly obscure. Stylised samurai cinema only gained respect on the arthouse circuit, though the home video market would later help to build them a cult following. The recasting and re-telling of stories within a more familiar western framework was a quicker draw at the box office outside of Japan.

Yojimbo was hugely influential in Japan and abroad and spawned numerous imitators. Most notably, Sergio Leone saw it whilst writing A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and it left a lasting impression. Watch both films back-to-back and you’ll see many sequences could be following the same storyboard!

They also have prime plot devices in common. In both, the cool man of few words serves two masters who are at odds with each other, playing a risky game that sets two rival gangs against each other. There’s a woman in jeopardy in both, separated from their child. There are several stand-offs where the protagonist is outnumbered—but efficiently, almost clinically, dispatches his challengers. The motivations of both central characters are ambiguous, and each film is supremely stylish and absorbing. These two films changed their respective genres irrevocably. I love both versions!

Can Fistful really be called remake of Yojimbo, though? Leone tried to make out otherwise, but Kurosawa filed a lawsuit that changed his mind. In an out of court settlement, Leone admitted that Fistful was basically an unlicensed remake, paid a lump sum to Kurosawa and reportedly signed over 15% of the profits as a retrospective fee. But did he learn his lesson? Seems not, but maybe he learned not to mess with a tried and tested recipe. The third in his Dollars Trilogy—The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)—was also inspired by a classic samurai movie, Hideo Gosha’s debut Three Outlaw Samurai (1964). Again, I love both!

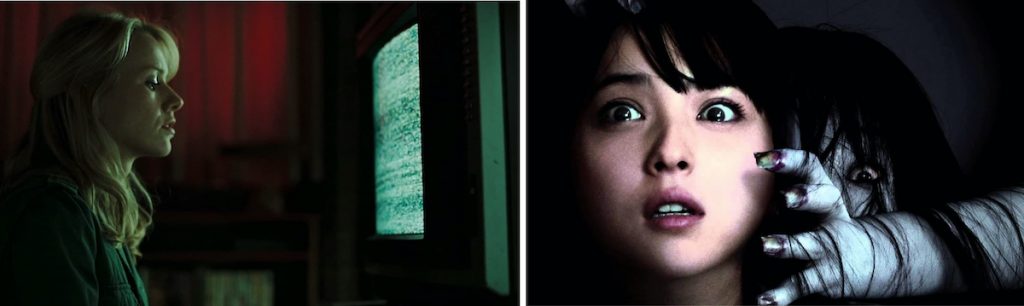

Hideo Nakata’s Ringu was a formative horror film that triggered the early-2000s ‘J-Horror’ craze. But while the likes of Audition (1999) and Battle Royale (2000) weren’t remade by Hollywood because they were too controversial, those that were usually flopped (The Grudge, Dark Water). The only significant outlier was Gore Verbinski’s 2002 remake The Ring, which established Naomi Watts after her Mulholland Dr. (2001) breakthrough and undoubtedly inspired a lot of westerners to seek out the 1998 original and make Japanese horror a big deal.

The success of The Ring is very simple: it’s a faithful adaptation with changes that only broadened its appeal, which also streamlines the narratives and avoids some of Ringu‘s sillier deviations. This is even more incredible because The Ring was written by Ehren Krueger (whose output fluctuates wildly between Arlington Road and Transformers sequels), but perhaps the genius of Kôji Suzuki’s 1991 novel is what really sucked in audiences. The concept of a cursed video tape is perfect horror fodder, and it’s lucky this remake arrived just before VHS became a relic.

With great performances from Watts and child star David Dorfman, together with a suitably oppressive atmosphere in rainswept Seattle, The Ring was a rare instance of Hollywood successfully capturing what made the original work. It grossed an incredible $239M from a $48M budget, but the 2005 sequel (directed by Hideo Nakata himself) was a comparative flop with $164M banked. They even made an unwise 2017 sequel called Rings that only clawed back $83M. But at least we have this turn-of-the-millennium chiller to prove that what scares the east can scare the west.

Erik Skjoldbjærg’s original Insomnia is so dependent on its location (Norway above the Arctic Circle) that when Christopher Nolan remade it for Hollywood, it could only have been set in one place: the evocatively-named Alaskan town of Nightmute… which, just like northern Norway, goes through months of perpetual daylight each summer.

To Nightmute comes an already weary LAPD detective, Dormer (Al Pacino), despatched to help investigate the murder of a teenage girl. Soon he’ll grow even wearier, and then exhausted, as the endlessly bright sky, the pressures of the case, and his own sins catch up with him.

Pacino excels as a man drawing closer and closer to physical and spiritual collapse; his haggard face betraying his guilt and anxiety. Robin Williams, in one of his rare bad-guy roles, reminds us how good he was at them, while Hilary Swank is charismatic as a local cop.

Nolan, then a hot newcomer following Memento (2000), tells the story with style but less flamboyance than in some of his later films, making the most of light, earth, air, and water. (It was mostly filmed in British Columbia, not Alaska.) But despite so much of the story taking place in the great Alaskan outdoors, it’s a hemmed-in, anxious film. The New York Times described it as “a cat-and-mouse game in which the mouse feels its pursuer’s breath on its fur and the cat is burdened with shame.”

Adapting one of Hong Kong’s best loved thrillers isn’t an easy feat, but if anyone could do it, it’s Martin Scorsese. The thrilling Infernal Affairs was a hit with critics and audiences alike, telling the suspenseful story of two police officers working undercover on different sides of the law. One infiltrates a triad gang, while the other rises in the ranks and acts as a mole for the same outfit, yet both become increasingly paranoid and desperate to end their double lives.

With his remake, The Departed, Scorsese transplanted this cat-and-mouse game to the Irish-American crime scene of South Boston, where ideas of identity and masculinity come together to create a well-paced and entertaining crime drama. Billy Costigan (Leonardo DiCaprio) is the neurotic but principled undercover cop infiltrating the gang of crime boss Frank Costello (a truly unhinged Jack Nicholson), while Colin Sullivan (Matt Damon) is the slimy, double-crossing mole embedded in the Massachusetts State Police but actually working for Costello.

Scorsese’s masterful direction is bolstered by William Monahan’s dynamic screenplay and the outstanding ensemble cast. From Martin Sheen doing his best Mayor Quimby impression, to a wonderfully vulgar Mark Wahlberg, everyone is on top form. However, the finest performances come from DiCaprio and Damon, who create a wonderful contrast of decency versus corruption between their characters.

Thelma Schoonmaker’s editing ensures this is one of Scorsese’s tightest films to date, trimming the fat and creating a lean classic to add to his already definitive work on organised crime. Smartly written and aggressively Boston at heart, the film would go on to win Martin Scorsese his first and only ‘Best Director’ Academy Award. Although he should have won an Oscar much sooner in his prime, The Departed is still one of the best works of his latter career.