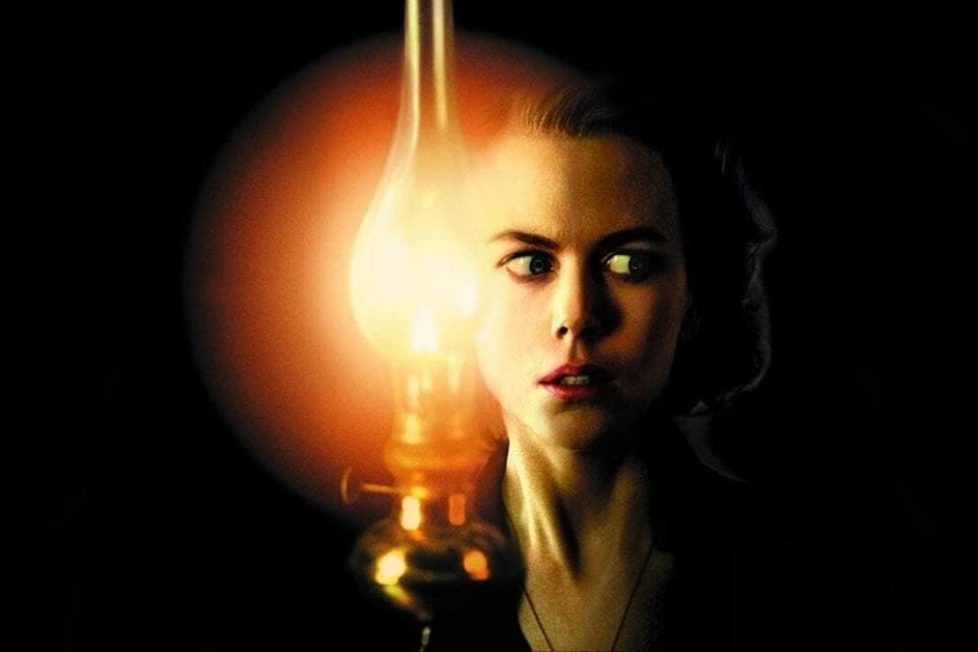

THE OTHERS (2001)

Shortly after the end of the Second World War, a widow living with her two young children becomes convinced that their house is haunted

Shortly after the end of the Second World War, a widow living with her two young children becomes convinced that their house is haunted

The new millennium ushered in a resurgence of intelligent horror films which had often seemed overshadowed by the slashers, bloodbaths, and satires that came to dominate the genre in the 1980s and 1990s. Traditional ghost stories were revived with modern twists by Hollywood, thanks to the likes of Robert Zemeckis’s What Lies Beneath (2001) and M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense (1999). Internationally, Japanese horror achieved global success with Hideo Nakata’s Ring (1998), while Spanish filmmakers also put their stamp on ghosts stories with Guillermo del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone (2001).

Alejandro Amenábar’s The Others remains one of the most prominent of the period’s ghost tales, and in some ways spans the Hollywood-to-world divide. It’s a very Spanish film—stylish, sensual, passionate—but in English and with English-language stars. The stiff-upper-lip 1940s British milieu in which it’s set seems fundamental to the movie (one can easily imagine someone like Celia Johnson in the Nicole Kidman role), yet the story was originally intended to take place in Chile, and the ever-so-British house at its centre is, in fact, the Palacio de los Hornillos—designed by a British architect but located in Cantabria.

The film’s strongly related to both English-language and Spanish products, too. It bears a clear resemblance to The Sixth Sense in its devastating pay-off (though Amenábar started writing it before Shyamalan’s movie was released), and may even have been partially based on an Armchair Theatre episode of the same name from the 1970s. But in its concern with motherhood, it’s also the clear ancestor of that other superb Spanish ghost story of the period, J.A Bayona’s The Orphanage (2007).

The Others is a slow-burn (fittingly, because it turns out to be dealing with eternity), that relies more on a build-up of disquiet than jump scares. It’s old-fashioned too, as Amenábar’s own musical score could easily come from the mid-20th-century, the focus on a neurotic woman is pure 1940s, and there are echoes of Henry James’s novel The Turn of the Screw. But it’s also a more thoughtful film than it might initially seem. Superficially The Others is all about delusion, portrayed rather melodramatically, but look a little deeper—beyond the obvious is the whole point, in fact—and it’s also concerned with self-awareness, healing, and even the nature of knowledge itself. The Others presents two coherent but mutually contradictory worlds and asks us, and its central characters, to figure out which of them is real.

The location is the Channel Island of Jersey, shortly after the end of World War II. Grace (Nicole Kidman) lives in a large country house with her two young children, Anne (Alakina Mann) and Nicholas (James Bentley). Her woes are many. Her husband has apparently been killed in the war, and she constantly has to protect her children from sunlight lest it triggers a rare skin condition—but even so, they don’t seem to quite explain the overwhelming sorrow, pain, and fear that beset Grace. She doesn’t seem to understand why her unhappiness is so intense, either, and her fierce religious beliefs (the film starts with a narration of the Creation story) provide more dread than consolation.

Shortly before the beginning of the movie, the household’s servants have inexplicably decamped and Grace hires a trio of replacements: Mrs Mills (Fionnula Flanagan) as a housekeeper, Mr Tuttle (Eric Sykes) as a gardener, and the mute Lydia (Elaine Cassidy) as a maid—who’s younger than the others, but “older than she looks”, according to Mrs Mills.

They had, indeed, worked at the selfsame house in the past, but had to leave “on account of the tuberculosis”, the housekeeper explains. As the film progresses, it becomes increasingly obvious the servants have an agenda and know something Grace doesn’t… but what? And at the same time, her daughter is adamant there are unknown other people in their home.

It’s not until halfway through that Grace acknowledges “there is something in this house”. Audiences will, of course, have done so long before. In a rich, layered screenplay, originally written in Spanish until executive producer Tom Cruise insisted the film be shot in English. there are blatant clues. For example, Grace discovers Victorian photos of the dead posed as if alive, one of them incidentally played by the director. And there are countless less obvious ones too—like the way that the phrase “stop breathing” is used twice. Recognising these may make the trajectory of the story seem obvious, but Amenábar has some big surprises up his sleeve, and the climax of the film is a reveal upon reveal, and all the more effective because viewers have already congratulated themselves, prematurely, on figuring it all out.

Re-watching the movie once its secrets are known, the sheer quantity of hints can become almost comical. At times it seems that every line spoken by Mrs Mills, in particular, has a double meaning. But even though there’s a trace of Gothic camp in the way the servants are rendered, for the most part The Others is serious without being excessively solemn. Conversations like Grace’s with her children on the subject of hell and limbo provide insight into the characters’ perspectives rather than force-feeding us with ideas.

Still, ideas there are aplenty, most of them revolving around Grace. She’s the main concern of the film and often manifested expressionistically. Her fear of admitting light into the house is an obvious case: she’s hiding her children, and herself, from the truth, and when the mysterious Others remove all the curtains, it’s the beginning of revelation. In the end, understanding herself enables her to overcome her neuroses and become closer to her children. She may lose her religious faith but she replaces it with a strengthened faith in her family. These concepts are never dominating in The Others, which works perfectly well as a straightforward ghost story too, but they’re plain enough to see and place the film squarely in a tradition of psychiatrically-influenced tales of the supernatural.

Buried a little deeper, intriguingly, is the possibility that the Jersey setting isn’t accidental. The Nazis had occupied the island from 1940 to 1945, and collaboration by locals with the Germans was a highly sensitive point in the aftermath. Indeed, it remained so many years later, and the whole episode has hardly been addressed in cinema. If Grace had been a collaborator this might be a further explanation of her guilt and her desire to remain concealed, as well as providing a new perspective on her relationship with her husband (a small part in the film played by an underused Christopher Eccleston). There’s a telling exchange where she observes that war is about “goodies and baddies”, to which one of the children responds “how do you know who the goodies and the baddies are?”

This interest not only in the emotional lives of its characters but also in the questions of what they know and what they are hiding is reflected in the visual style of Amenábar, along with cinematographer Javier Aguirresarobe, and production designer Benjamín Fernández (the latter a Hollywood veteran in a crew largely drawn from the Spanish film world). Interiors are dark and exteriors soaked in what Grace calls “everlasting” fog, emphasising her family’s state of ignorance. There’s much use of chiaroscuro for the same purpose, with Kidman’s face frequently being half-lit. Windows and mirrors (gateways to knowledge or self-knowledge) appear often too, and many scenes are tinged with a spectral, sickly grey-green.

Amenábar doesn’t completely avoid horror clichés (the door lit from behind, white bedsheets on furniture, a child’s sinister drawing), but he uses them sparingly, to anchor The Others in the genre than for their own value. Similarly, though there are a few jumps (most notably Kidman screaming on her bed early on, shot at a Dutch angle), the power of his film comes much more from accumulated tension and mystery than from individual incidents. “Many films end up just being a parade of special effects and sounds effects,” he’s since said. “That can be really, really impressive, but for me, I try to work on the opposite level with a quiet film, playing with silence and playing with darkness, the most primary fear.”

This low-key approach didn’t win over all the critics, especially outside of Spain, although it won ‘Best Film’, ‘Best Director’ and ‘Best Original Screenplay’ at the Goya Awards, Spain’s major film prizes. And although it did well at the box office, its commercial success was most notable in its own country too. David Denby in The New Yorker found The Others “extremely skilful” but also warned that it “becomes monotonous”; Roger Ebert, likewise, praised the “languorous, dreamy atmosphere” but felt “Amenábar is a little too confident that style can substitute for substance.”

One strength of the movie that united most of them, though, was Kidman’s performance. Nick James of Sight & Sound (who loved the movie overall, asking “who’d have believed that the uncanny in its most moth-eaten Miss Havisham clothes could still put the willies up the sated, seen-it-all modern moviegoer?”) wrote of her Grace that “seemingly genuine feeling shifts brilliant technique to a higher level”. And, indeed, she’s never less than absolutely believable as a ’40s woman, or (more accurately) as the kind of highly-strung, perpetually anxious woman played by ’40s Hollywood stars in psychological dramas.

The children are compelling too. Mann commands entire scenes with her sassy, smart, adamant attitude, while Bentley draws the attention in the opposite way. He’s timorous, even miserable, and dominated by her. Flanagan’s housekeeper, meanwhile, manages—like the whole film—to be slightly OTT in a spooky way without becoming ridiculous, with the knowledge she’s withholding from Grace well expressed in her face.

There’s little in The Others that doesn’t work, although one scene is perhaps a little confusing until after the event, and although the sound design is clever the contrast between near-whispered dialogue and sudden aural shocks makes it an awkward film to watch on TV. (Its flaws being so minor, it’s difficult to see what the remake reported to currently be in development can add, particularly given that so much of the film’s impact depends on the final revelations which will be familiar to so many potential viewers.)

Amenábar’s slight tendency toward dramatic and visual excess may not be to everyone’s taste, but there’s not a moment of The Others that seems out of place or contrived, no point where the story and the style seem less than seamlessly blended, and the script suggests ideas far subtler than the occasionally lurid surface might reveal. The result is a superb modern ghost story, demonstrating how the skilful reworking of familiar elements can remain powerful in the 21st-century.

SPAIN | 2001 | 104 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Alejandro Amenábar.

starring: Nicole Kidman, Fionnula Flanagan, Christopher Eccleston & Eric Sykes.