The Films of Olivier Assayas (1986-2002)

A review of Arrow Video's box-set 'The Films of Olivier Assayas' (Disorder, Winter’s Child, Irma Vep, and Demonlover).

A review of Arrow Video's box-set 'The Films of Olivier Assayas' (Disorder, Winter’s Child, Irma Vep, and Demonlover).

Olivier Assayas is one of the most inconsistent directors to come out of post-New Wave French cinema. Unpredictable may be a kinder way to put it because one never knows what to expect. They’re usually intriguing, sometimes astonishing, often disappointing, but always worth the risk. They’re likely to veer off into a totally different genre from their starting point and must be a nightmare to market. A couple of things that remain constant are an impeccable musical taste, showcased in scores that perfectly meld with the visuals, and the impression we’re seeing exactly what Assayas intends for us to see. For better or worse.

He’s sometimes lumped in with the so-called New French Extremity wave, and was probably a spark for the style now notorious for its unflinching cruelty and violence, along with sweaty, awkward sex that lacks any element of eroticism. Think Xavier Gens’ Frontière(s) (2007), Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs (2008), and Nicolas Winding Refn’s The Neon Demon (2016). However, when viewed from that perspective, the films of Assayas would be the most moderate of that ill-defined genre. When he offers us violence, it’s brief, brutal, and bloody. As for sexual content? Well, he doesn’t shy away from it but can handle a scene of first love with a poetic touch, or a rape scene that’s appropriately shocking and ugly.

Assayas is a critic turned filmmaker and perhaps has a tendency to over-think things as a result, making films for other critics rather than general audiences. He was raised in a cinematic family and helped his father, Raymond Assayas, write screenplays before becoming a critic for the influential, some might say politically-motivated, French film journal Cahiers du Cinema. Once there, he rubbed shoulders with writers who would turn out to be fellow ‘bad-asses’ of the second wave of Nouvelle Vague directors, including Serge Daney, André Téchiné, Léos Carax, and Danièle Dubroux.

Assayas is also known for courting controversy in both his personal and professional life. He sat on the judging panel at Cannes 2011, adding his voice to the Terrance Malick versus Lars Von Trier furor when Trier made an anti-Semitic joke at the press reception about having some sympathy for Hitler. Assayas said that they were there to judge only what’s on the screen and not the off-screen morality of individuals. He also spoke out in support of director Roman Polanski and they would later collaborate on the script for Based on a True Story (2017).

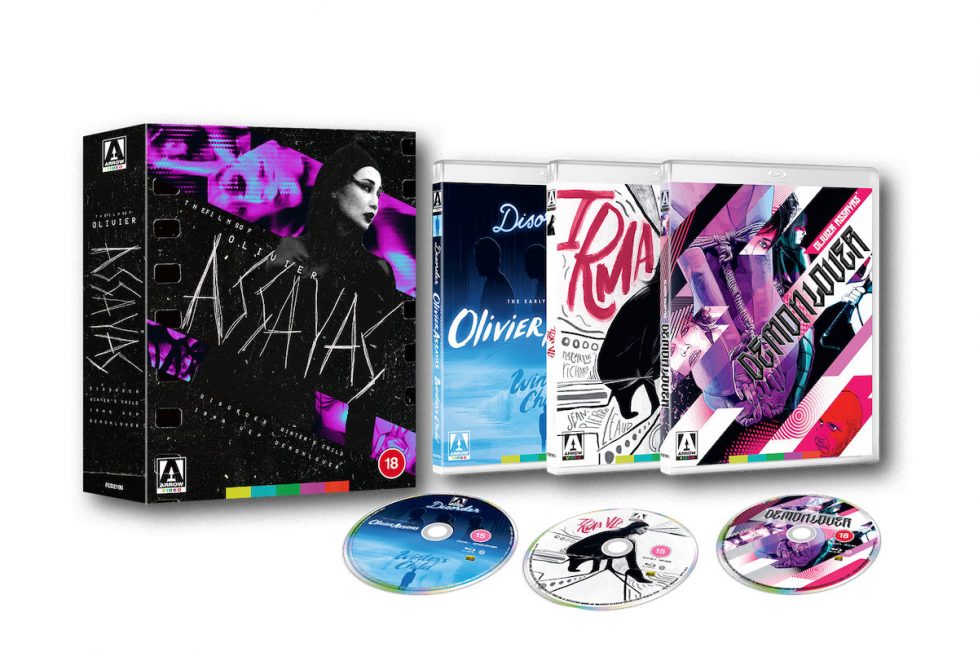

This new Arrow Video box set gathers a set of films that take us from his mid-1980s debut, Disorder (1986), via his lowest point with the dreary dysfunctional relationship drama, Winter’s Child (1989), to the pinnacle of his artistic powers in the unique Irma Vep (1996), and sees-in the new millennia with the troublesome Demonlover (2002). It’s a fair cross-section of the first half of his career. So, calling the collection The Films of Olivier Assayas makes it sound more of a complete overview than it is. Nevertheless, if you’ve missed their previous releases from the now-defunct Arrow Academy imprint, it’s a good opportunity to catch up with these four films, which are all nicely restored and presented in their director’s cuts with plenty of extras.

A French corporation goes head-to-head with an American web media company for the rights to a 3-D manga pornography studio, resulting in a power struggle that culminates in violence and espionage.

Frustratingly, Demonlover promises great things it never delivers. We’re sucked in with a super-slick, technically accomplished sequence that gradually eases us into the milieu of an international espionage thriller. Nearly everyone’s asleep on the business class flight as the muted monitors show snippets of explosive violence from some mainstream action movie. But there’s always one inconsiderate bustard of a boss—in this case, Henri-Pierre Volf (Jean-Baptise Malartre)—who insists on staying awake to dictate a report to his assistant, Diane (Connie Nielson).

This immediately lays out the central theme of the dominant and subservient—those who control and those who are controlled. Also, a pervading mood of tiredness as no one seems to get much sleep for the rest of the film which turns out to be a soporific experience all-round. This is why it’s most intriguing when Diane palms an Evian from a breakfast tray on her way to the toilet, where she spikes it with haloperidol, a powerful tranquiliser.

She returns the spiked drink to her colleague, Karen (Dominique Reymond), who’s subsequently abducted from the airport on their arrival in Tokyo, and bundled unconscious into her jet-black Audi TT–which had already been talked about as an object of desire denoting success. We then learn that our protagonist, Diane, is actually a calculating and callous double-agent who’s drugged her superior so she can take her place. She wants access to sensitive documents surrounding a deal that Volf is brokering with a Japanese anime company for sole distribution rights for their entire output. What she hadn’t reckoned on is an equally ruthless rival in the young Elise (Chloe Sevigny), who had been Karen’s secretary.

While in Tokyo it becomes apparent the anime company also has a far less salubrious line in internet porn websites, one of which being ‘The Hellfire Club’, an illegal and apparently highly lucrative torture site that allows remote user participation. Overseen by the sleazy Hervé (Charles Berling) on behalf of Volf, the art of the deal seems to be to include control of the illegal sites in the contract without becoming liable for any legal recriminations whilst also outbidding all other interested parties. Things quickly become yet darker as international connections with organised crime are revealed and it becomes clear that no individual will be allowed to get in the way of the corporate deal.

There are moments of pure poetic Kodachrome beauty, consummately handled by Assayas’s trusted cinematographer, Denis Lenoir. The clinical hotel interiors and deserted Tokyo streets in the early hours are so precisely shot to evoke that distinctive chill and portentous promise of a new day. Later, the abstracted colours of streetlights and traffic through rain-streaked windscreens, doused in the dreamy strains of Sonic Youth’s unconventional tuning, are equally evocative.

These interludes almost save the film from itself, but they don’t persist nearly long enough. All too soon, those pesky characters are back to spoil things, just a parade of shallow people having pretentious conversations about themselves. You wouldn’t want to be in their company for long and eavesdropping as an invisible spectator separated only by the surface of a screen is just as tedious.

Back in Paris, things briefly liven up with the arrival of Elaine (Gina Gershon), representing US interests. Diane goes a bit ‘Irma Vep’ by donning black cat-burglar gear before breaking into Elaine’s apartment to retrieve information about what sums have been offered by rival companies for the US rights. It’s here that a major complication arises when Elaine comes back unexpectedly and discovers Diane. The two glamorous women engage in a most unglamorous blood-soaked tussle, and we finally have confirmation that there are no good guys here at all. This is the film’s high point and from here on, everything falls apart, including the plot—which I’m sure Assayas would defend as a cleverly fractured narrative.

The first half is engrossing but it all culminates with an end twist that’s such a cliché, one is left pondering the director’s intentions. Is it supposed to be chilling, shocking, or tragically inevitable? It ends up being a relief for the viewer as the unpleasantness had become somewhat grueling since it overtook and separated itself from the plot. Well, there’s not so much plot per se. It’s more a collection of points-of-discussion peppered across a slight story held together with recurring motifs. There’re plenty of visual nods to Irma Vep, but this only reminds us how meticulously scripted and supremely cool that film was and how unlike it Demonlover finally is.

The hook for the first half was trying to figure out Diane’s motivations. I’m not sure we ever get to know what drives any of the characters. Except maybe their base primal impulses and narcissistic nihilism. It seems to be condemning pornography and violence, or indeed violent pornography, but it contains suitably shocking scenes of that ilk, though Assayas never gives us clear cues of what he expects in terms of audience response. Evidently, he’s not expecting us to be entertained, though!

The violence is clinically explicit and matter-of-fact, the pornographic elements less so. Is that because he considers violence more or less shocking than sex? Good question and perhaps he’s offering a premise that, in some (hopefully rare) cases, the intentions behind both are interchangeable. The problem is, he never offers a ‘control sample’. All the imbalanced interactions are loaded, transactional, and exploitative which finally comes across as simply misanthropic. This examination of power and control in dysfunctional relationships is perhaps a broad metaphor intended for interpersonal intercourse, office politics, corporate-level wheeling and dealing, the failed diplomacy between governments, international trade, and big-time crime.

Assayas has said that he’s not entirely focussed on storytelling but endlessly fascinated with the interaction of reality and fiction—the point where the actor and character intersect. A problem with that approach becomes apparent when there really isn’t much overlap. In this case, it leaves little for the actors to work with, so the performances just seem shallow and slight.

Certainly, the cast of Demonlover delivers moments of intensity and I’m sure some of the scenes—I’m thinking sweaty rape combined with bloody revenge killing—must’ve been hugely challenging. But for the most part, the performances are so minimal that their understatement results in too much ambiguity and offers little chance of any surprise revelations. That works well for the first half, whilst the viewer is hooked on trying to figure out the motivations for the central characters, but the fascination wears thin as the film fails to deliver anything that goes deeper than that surface. The persistent ambiguity implies subtlety where there turns out to be none.

FRANCE • MEXICO • JAPAN | 2002 | 129 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | FRENCH • ENGLISH • JAPANESE

The best thing about Disorder is the young cast and the youthful vibrancy they bring to their roles. It is an enduring strength of Assayas that he can elicit intense and natural performances form young actors.

Remy Dean’s original Blu-ray review, 6 October 2018

… a French arthouse movie cliché throughout, the men are moody, immature, and selfish, while the women are emotionally fragile or downright mentally unwell and in need of help the men in their lives can’t provide.

Remy Dean’s original Blu-ray review, 8 October 2018

Everything about Irma Vep is super cool. Maggie Cheung’s latex-clad Irma is an icon in waiting. One of my favourite scenes, where Maggie ‘becomes’ Irma, is set to Sonic Youth’s “Tunic (Song for Karen)” with its “Goodbye Hollywood” lyric.

Remy Dean’s original Blu-ray review, 6 May 2018

Other special features have been reviewed for their standalone Blu-ray releases here and here.

writer & director: Olivier Assayas.

starring: Connie Nielsen, Charles Berling, Chloë Sevigny & Gina Gershon (Demonlover) • Wadeck Stanczak, Ann-Gisel Glass & Lucas Belvaux (Disorder) • Clotilde de Bayser, Michel Feller & Marie Matheron. (Child) • Maggie Cheung, Jean-Pierre Léaud, Nathalie Richard, Bulle Ogier, Lou Castel, Arsinée Khanjian, Antoine Basler, Nathalie Boutefeu, Alex Descas & Olivier Torres. (Irma)