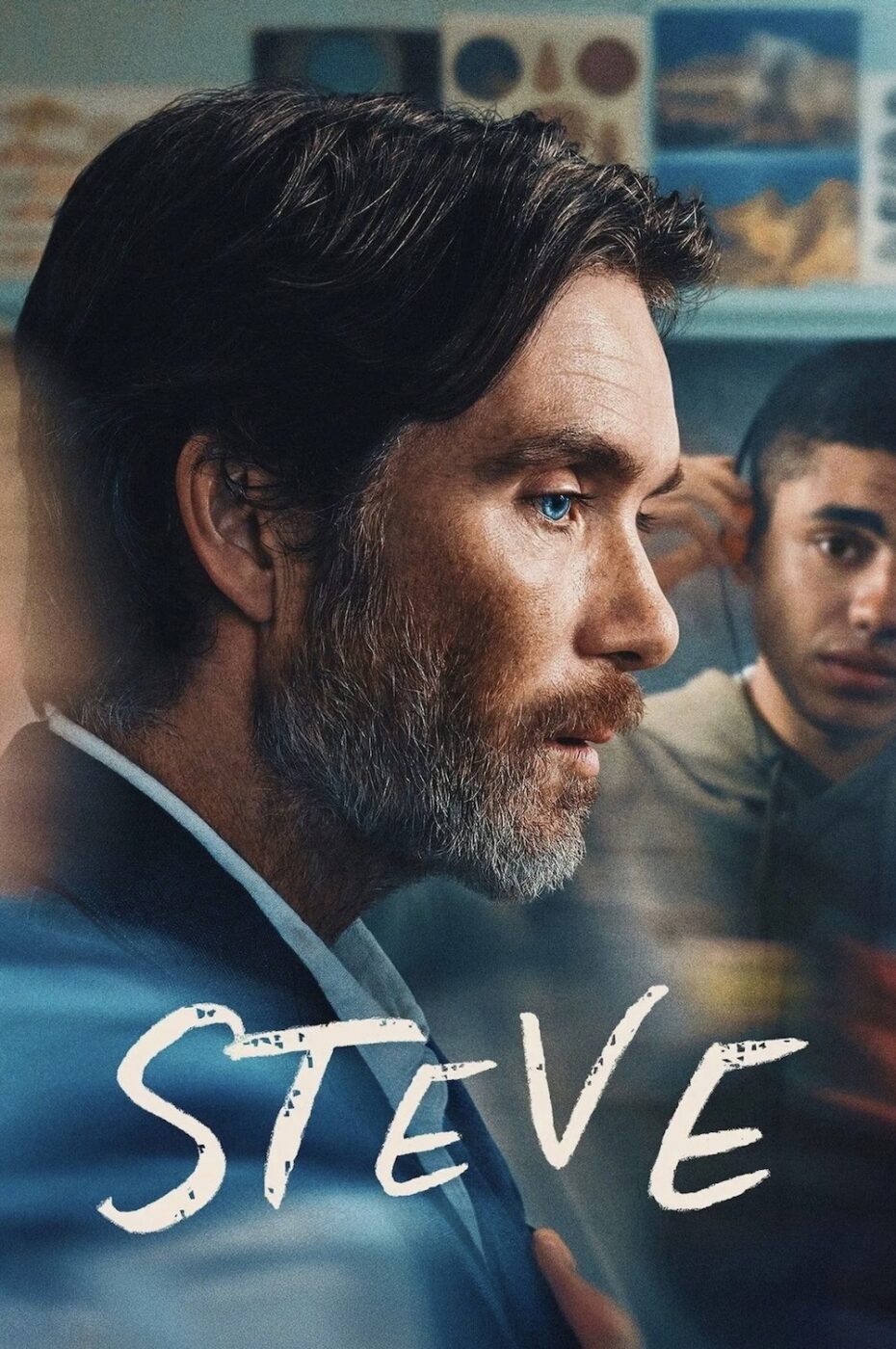

STEVE (2025)

A headteacher battles for his reform college's survival while managing his mental health.

A headteacher battles for his reform college's survival while managing his mental health.

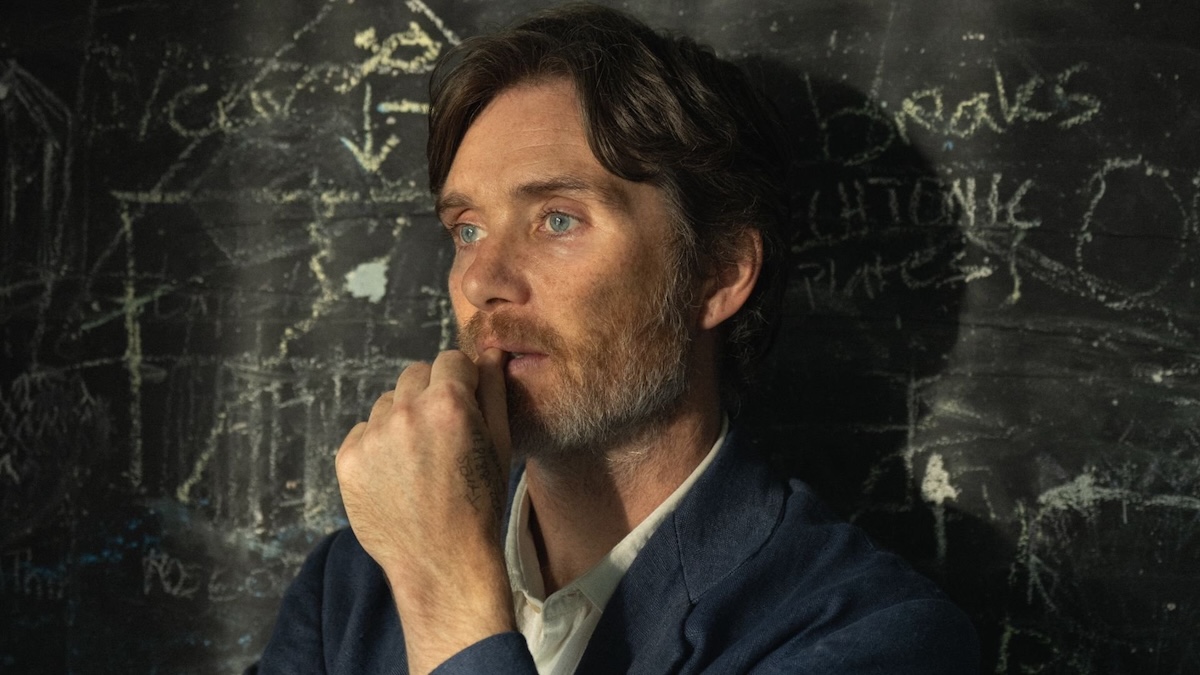

The wave of phenomenal performances from Cillian Murphy continues to march forward each year. A talented actor who has demonstrated his abilities in mainstream and independent films for over two decades, it wasn’t until his leading role in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023) that Murphy was finally given a role that could speak to the seemingly bottomless depth of that talent. He’s an actor whose face appears to change entirely based on the characters he plays, though these chameleonic abilities aren’t always required for him to craft a stellar performance. The Irish actor is at his best when he’s able to showcase the physical and emotional characteristics of a ravaged psyche. He acts just as much with his eyes as with his facial expressions, wearing sorrow so adeptly that it’s not just that his wordless emotions don’t seem performative, it’s impossible to imagine that any effort was placed in contorting himself to convey this pain.

For this reason, sensitive, intimate filmmaking draws out his acting ability to its strongest degree of emotional potency, something that Tim Mielants’ anguished, small-scale film Small Things Like These (2024) does far more often than Nolan’s decades-long story of the complicated man behind one of the most destructive acts in human history. A far more intimate historical drama, Mielants’ work is so attuned to the repetitive rhythm of protagonist Bill Furlong’s (Murphy) existence that witnessing his tortured expression amidst his mundane existence is a fresh wound each time. Forced to reckon with inhuman practices that were commonplace and condoned in 1980s Ireland, Bill’s not an epic figure. He’s an ordinary, quiet family man forced to contend with the weight of his traumatic past and the tragic reverberations of the Catholic Church’s generations-spanning grip on Irish society. Murphy’s eyes are a piercing blue, a well of sorrow so profound that he’s at his most captivating when his characters are silent, with Bill often finding himself paralysed by indecision and psychic trauma.

This quality carries over beautifully in the second collaboration between Murphy and Mielants, Steve. With a very limited release in cinemas prior to its arrival in the streaming space, the film has only made its presence known to mainstream viewers this weekend. It marks the third consecutive time where Murphy has produced one of the finest performances of the year, this time transforming himself into the eponymous Steve (Murphy), a headteacher of a school for teenage boys with behavioural difficulties. The kids themselves are a nightmare, full of rage and venom, while the teachers are pitted in a constant struggle to break up fights and heal these youngsters’ broken hearts. They must give their students enough practical, educational, and coping skills to eventually navigate a world far more unforgiving than this coddling habitat that they take for granted. Mielants and screenwriter Max Porter, who adapted the film from his 2023 novel, Shy, are by no means reticent to explore just how much dread these working conditions evoke.

Free of schmaltzy sentimentality (for the most part, at least), Steve is a dire and desperate plea for empathy that knows there are no easy solutions for how to steer a damaged young person in the right direction. What is most remarkable about this protagonist is how often he mirrors his troublesome students. To them, he’s a typical teacher in that it’s almost a God-given assurance that he’s lame and out of touch (even if it’s clear they are still able to form a bond with him), but in his conduct with co-workers he’s just like one of the restless teens. He can’t sit still for more than a few seconds, fidgets with his hands, races through sentences like he has five other places to be, doesn’t always behave in a professional manner, and keeps putting off his various responsibilities. On that lost front, this is hardly a worthy area to criticise Steve, who tirelessly soldiers through a chaotic day that unearths drama and trouble so steadily it’s hardly a surprise when new calamities emerge.

He’s a good teacher, but he’s also drowning in his responsibilities. He has too many burdens and so little time to address them, often straying from his main focus of the day: reaching out to Shy (Jay Lycurgo), a damaged young man who has been spiralling as of late. The arrival of a film crew marks yet another roadblock, as regular duties grind to a halt to accommodate these nosy new arrivals and their desire to record footage for a news segment about the school. The crew are contemptuous towards the teens, and while the youngsters’ behaviour appears to warrant this viewpoint, itis very much the perspective of a haughty outsider to dismiss the anguish that lies before them. By drawing us far closer into this world than the news crew will ever understand, Mielants and Porter trust viewers to see that there’s a much more complicated, even beautiful, portrait in motion.

Watching Steve is an incredibly stressful experience, from the film’s hectic editing, swooping camera movements, tracking shots, sudden outbursts, constant diversions, and yet another staggering lead performance from Murphy of a man in a state of perpetual crisis. This protagonist is unable to focus on anything before his attention is wrenched away from one temporary subject to another in an endless rotation, provoking anxiety mere minutes into the film. Most stress-inducing films make your heart race by portraying characters who are giving everything they can to pursue a single goal. That could be pulling off a bank heist or trying to evade someone who wants them dead, but whatever their particular bind is, it typically involves a clear end goal and even clearer obstacles in their way.

In Steve, these teachers aren’t on a linear path at all. Their day begins with relatively few problems, but not only do these gradually mount, the age-old adage that when it rains it pours could not be more true here. They don’t have a single goal they must pursue. Instead, there are constant problems, some of which must be addressed instantaneously, like having to hurtle yourself between two teenagers hellbent on attacking each other. If that’s not unwelcome enough, there are the long-standing issues that have no easy answers. Shy’s depression has considerably worsened as he abandons his healthy coping mechanisms, gives in to unhealthy ones, and is left reeling from a phone call with his mum where she cuts off contact with him. How do you approach a rebellious, frustrated teenager who doesn’t want to be helped? How do you save someone squarely focused on their demise?

It’s difficult to tell whether the problem is that there aren’t easy answers to these questions, or that there aren’t any good answers. Steve is realistic about the nightmarish reality of working with these kids, refusing to shield their worst qualities and resisting the urge to make them wounded in a cloying way. Many of their outbursts are cries for help, but only deep down. On the surface, they’re still laced with a rage and vindictiveness so pronounced that it’s a wonder these teachers aren’t constantly fearing for their safety. Steve, though far calmer, is unafraid of these teens because he sees himself in them. Cracks in his psyche and resolve gradually widen throughout the film, until it becomes clear that many of his mannerisms, speech patterns, and habits are covert cries for help. He doesn’t even realise it in these moments, but there’s a deep-seated part of him begging for comfort, expressed similarly to these teenagers’ poor behaviour.

By moving the schoolhouse action from a typical classroom environment to an isolated, self-sufficient centre for troubled kids, the role of a teacher as an emotional and spiritual guide is enhanced greatly. A hero looking to save others who is in dire need of being saved is a standard formula, but it’s approached so sensitively by Murphy that it’s a marvel to watch Steve try to run away from his self-loathing as it continues to consume him, doggedly pushing on in his desire to reach out to the repressed teens. The hypocrisy is so stark it would be amusing if it weren’t so tragic for this protagonist to fail to glimpse it. Sometimes, these teachers are so immersed in the lives of their students that they fail to witness alarming signs that will gradually become apparent to audiences.

It’s masterful how Steve is constantly chaotic yet so exacting in its characterisation that you can read these characters like a book, feeling your anxiety rise in conjunction with theirs. Chaos is routine, so the film’s unique visual style is fairly adept at communicating the pressure of this day-in-the-life story. That said, the sweeping camera movements are often more distracting than they are hectic or awe-inspiring, especially when Mielants leans fully into music video territory with his offbeat direction. The textured, gorgeous cinematography of Small Things Like These isn’t present here, while that film’s sublime efforts to tug at viewers’ heartstrings and cause a lump to form in their throats are far more meaningful than the egregious emotional manipulation in Steve’s final minutes.

While Murphy and Mielants’ latest project keenly channels and expresses the urgency of youth, teaching and mental health crises throughout its 92-minute runtime, it veers off the rails with pretentious visual cues at key moments, building to an intense finale that is emotionally charged yet disappointingly maudlin. Its heart is always in the right place, but how it goes about conveying its starkest notes of tragedy and hope fail to cut bone-deep. The teen actors were excellent, but Lycurgo can’t pull off the tall order asked of him in this film’s denouement, while the eclectic visual palette works far better when it isn’t constantly trying to outdo its experimental streak. When the story hones in on Steve’s lack of focus amidst a day that feels both routine and relentless it strikes cinematic gold, especially when Murphy is at the helm with yet another heart-wrenching lead performance.

IRELAND • UK | 2025 | 92 MINUTES | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Tim Mielants.

writer: Max Porter (based on his own novel ‘Shy’).

starring: Cillian Murphy, Jay Lycurgo, Tracey Ullman, Simbi Ajikawo, Emily Watson, Luke Ayres, Joshua J. Parker, Douggie McMeekin, Araloyin Oshunremi & Tut Nyuot.