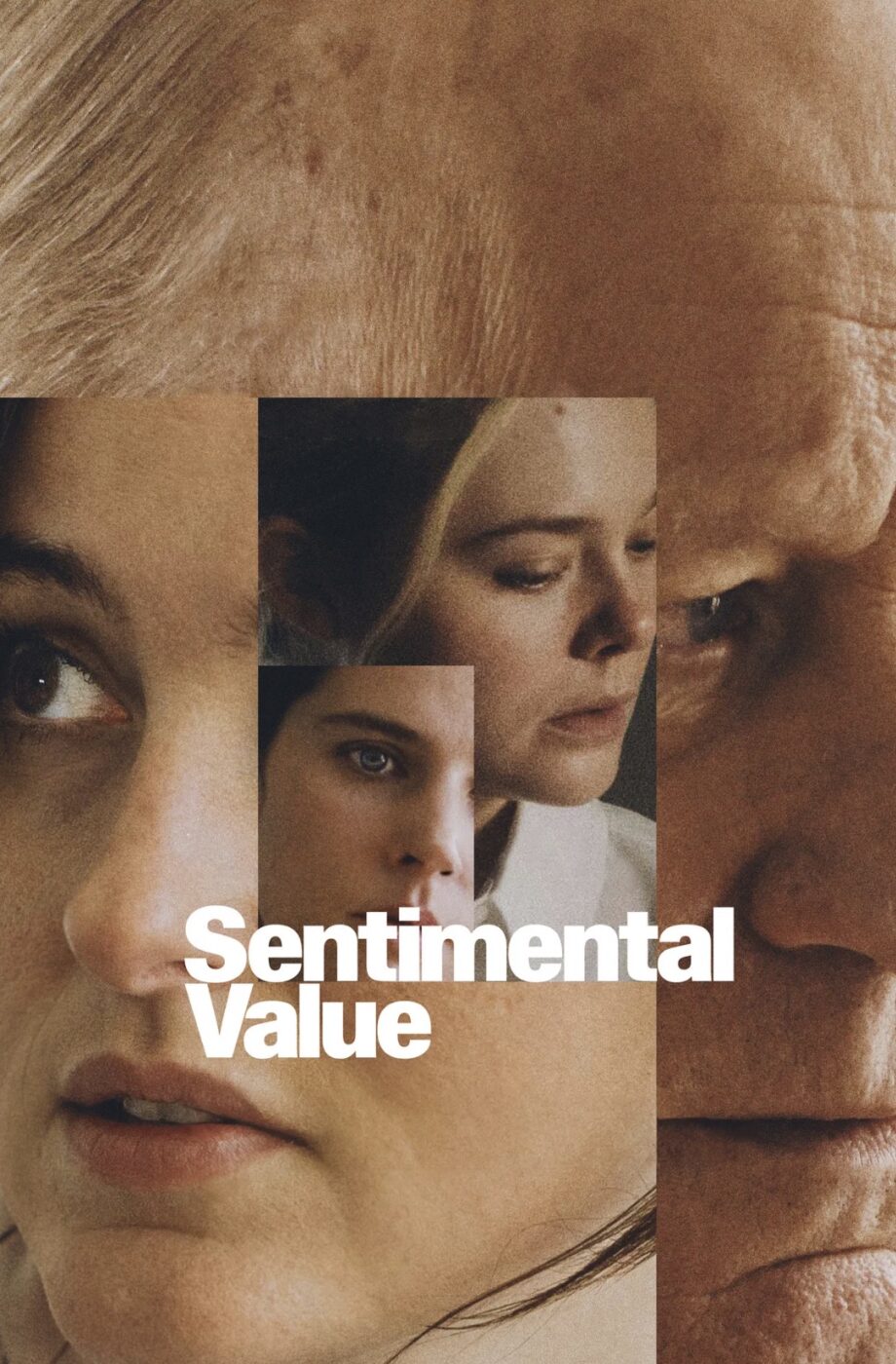

SENTIMENTAL VALUE (2025)

An intimate exploration of family, memories, and the reconciliatory power of art.

An intimate exploration of family, memories, and the reconciliatory power of art.

Director Joachim Trier’s Oslo trilogy—comprising Reprise (2006), Oslo, August 31st (2011), and The Worst Person in the World (2021)—is a body of work that explores a beautiful city no one seems able to leave. These are films about people who drift but never escape; Oslo itself is a gigantic playground where broken characters play out childlike fantasies or endure dark nights of the soul. Trier’s Oslo teems with invisible life—the city hums, yet its citizens feel like ghosts, leaving his protagonists as the only ones truly alive.

Trier’s latest film, Sentimental Value, returns us to Oslo, but someone has finally escaped. Gustav Borg (Stellan Skarsgård) is an acclaimed director with a storied career behind him. He’s reached the age where film festivals programme retrospectives of his work, and where he’s asked probing questions about his receding past and uncertain future. As a moderator points out, he hasn’t made a film in over a decade. He appears like a guest at his own wake—and indeed, it’s a funeral that has brought him back to Oslo, though not his own.

It’s the funeral of Sissel (Ida Marianne Vassbotn Klasson), Gustav’s ex-wife and the mother of his two daughters. We meet his children as adults, but flashbacks reveal the family’s fracture: Gustav was a heavy drinker, monomaniacal about his career, leading to an inevitable divorce. Gifted a newfound freedom, Gustav left the family home in Oslo to pursue his career across Europe and beyond. It’s in this same house that Sissel’s wake is now held.

Despite the looming presence of Gustav (and Skarsgård), this film is as much about those left behind as those who strike out on quests for self-fulfilment. Gustav would be reticent to describe his travels as ‘adventures’; he is self-serious and tortured. To him, it’s all work; none of it’s supposed to be fun. Perhaps this is how he justifies pursuing his own north star: it’s painful but necessary labour, and the suffering of the one causing the chaos is deemed punishment enough. Maybe Gustav was moved by the gods—or maybe he’s simply a narcissist who found being a husband and father remarkably dull.

His eldest daughter isn’t having much fun either. We meet Nora Borg (Renate Reinsve) backstage before a performance in which she plays the lead. Clad in a corset and headset, she stands amid avant-garde art installations as a portentous brass version of Dies Irae plays on repeat. It’s no wonder Nora is having a panic attack. She tears at her costume, unable to breathe, as producers scurry to calm her and keep the wardrobe intact.

She attempts some self-soothing by kissing her co-star, Jakob (Trier’s regular collaborator Anders Danielsen Lie), with whom she’s having an affair. It doesn’t work. She can’t get out, but the show must go on.

Nora’s younger sister, Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas), appears to have her life together, yet we sense that she, too, is panicking behind the scenes. An historian with a husband and son, Agnes shares a surprising commonality with her father. She writes books, he makes films, but both are trying to figure out what the past means and how to live with it. In Sentimental Value, the past is everywhere.

The Borg family home is where these lives converge; where the disparate family meets for the wake and where decades of memories settle in the dust. Imposing yet familiar, the house has a storybook quality, appearing as if it might belong to a witch. It’s panelled with aged wood in shades of brown and burgundy, set apart from the world by wild bursts of greenery. Trier, a director with a fine eye for the textures of memory, shows us the house through the decades. Dust particles dance in shafts of light while wooden walls creak in the sun; people play, fight, live, and die.

The house has been in the family since the 1800s. It belonged to Gustav’s parents, and now he has returned to claim it. However, he seems to take psychic damage from the building. Avoiding the mourners, he clomps upstairs to his old marital bedroom and sits despondently on the edge of the bed. For Gustav, as for his daughters, the home represents a shared history—a tie to something larger that is as suffocating as it is healing.

Gustav’s presence is similarly stifling. When he recalls Sissel, he describes her simply as “beautiful”. His daughters are “lovely”. There is no woman Gustav cannot reduce to an aesthetic summation. He is a man for whom everything exists on his own terms. Even when telling Nora he came to see her performance, he admits he didn’t stay until the end. ‘Theatre’s not my thing,’ he says with a blasé shrug, before needling her about leaving the stage. He insists she’s better than the role, both belittling and complimenting her in the same breath.

Gustav’s ulterior motives soon surface. He intends to make his next film: a drama shot in the family home, inspired by his mother’s life. She was part of the Norwegian resistance during the Second World War. After being captured and tortured, she was released at the end of the war and returned home. Years later, she took her own life in a small room at the back of the house.

After years of estrangement, Nora and Gustav’s first private moments consist of a glorified pitch meeting, complete with a script in a manila envelope. Nora has withstood years of her father’s maddening behaviour, but being asked to play her own grandmother, in the house where her grandmother died, is the final straw. ‘We’re not going to work together, Dad. We can’t even communicate,’ she tells him.

Trier’s verve as a director often lies in transcendent imagery—the world standing still in The Worst Person in the World, or the nocturnal bike ride through fire-extinguisher plumes in Oslo, August 31st. But it also manifests in his handling of time. While Sentimental Value allows years to fall away in seconds, its greatest impact comes from experiencing ‘real’ time in all its painfulness.

Each scene between Gustav and his daughters carries the weight of awkwardness, of a glanced watch, of an exit desperately sought. Trier and editor Olivier Bugge Coutté allow life to unfurl, cutting or lingering as the rhythm of the conversation demands—matches for those moments where everything and nothing is said.

Later, in one of the film’s most touching scenes, Nora and Gustav step outside for a cigarette. Against the deep blues of the evening and the glow of streetlights, they realise that nothing needs to be said. Nora offers her father the smile of a fellow troublemaker; two smokers sharing a vice that the world finds disgusting. A smoke break is an attempt to collect one’s thoughts—a respite where solitude is as essential as the nicotine. Throughout the film, Gustav tells his daughters they are like him; here, we see he might be right.

Yet for every moment of connection, Gustav erects a dozen barriers. He begins courting an American movie star, Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning), for his film. She is starry-eyed, and he needs the funding her name brings. She is likely wrong for the role—she asks if she will need a ‘Scandinavian accent’, a suggestion Gustav chuckles at—but he’s an ageing egotist who sees his fading glory reflected in her naïve eyes. Their relationship becomes an extended, manufactured ‘meet-cute’, starting with him hailing a horse and carriage on a beach at sunrise. Is this work, or a final gasp of whimsy before the despair returns?

Trier’s uncanny understanding of human relationships prevents Sentimental Value from falling into didactic moralising. Gustav’s films are presented neither as works of genius nor as mere self-aggrandisement. He is not a total villain, but he is someone you couldn’t tolerate for long. Trier’s films are funny without being mocking; they deploy warmth when it makes sense but never reach for hackneyed sentimentality.

In Oslo, August 31st, a character suggests that, looked at “without sentimentality”, his life is worthless. His friend asks, “How am I supposed to not be sentimental?” That is the question Trier has chased throughout his career. How does one separate the emotional from the practical?

In Sentimental Value, that question attaches itself to the mechanism of filmmaking. Is it healthy to turn one’s life into a public spectacle? When we talk about ourselves, our brains visualise a version of us—recalling ‘facts’ that are actually subjective stories. Everything we do is channelled through learned behaviours and inherited beliefs.

If Gustav is trying to reach beauty through a lack of sentimentality—trying to look at his life with the harsh light of objectivity—he has already failed. Trier might love cinema, but he knows it won’t save us. The humanity in his films lives outside the frame; two hours of moving images cannot contain the contradictions of a life that refuses to resolve.

Trier’s films poke fun at the romanticisation of misery while allowing us to feel that very pain. We are not distanced; we are perched just high enough to see the circles in which we run and the filters through which we peer. Sentimental Valueis that rare film: as warm and human as it is clever and probing. Like the house at its centre, it is furnished with decades of wisdom and memories—the kind we can never quite bring ourselves to leave behind.

NORWAY • GERMANY • DENMARK • FRANCE • SWEDEN • UK • TURKEY | 2025 | 133 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | NORWEGIAN ENGLISH FRENCH

director: Joachim Trier.

writers: Eskil Vogt & Joachim Trier.

starring: Renate Reinsve, Stellan Skarsgård, Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas, Elle Fanning, Anders Danielsen Lie, Jesper Christensen, Lena Endre, Cory Michael Smith & Catherine Cohen.