Take 5: Scariest Film Villains

Five of our writers choose their favourite movie villains for Halloween...

Five of our writers choose their favourite movie villains for Halloween...

When he walks into the room, the music stops. Not in reverence, but as if his very appearance sucks every sound out of the room, replaced with some eerie hum seemingly emitting from somewhere inside him. His face is pale as if painted with kabuki makeup. He has no eyebrows, and has no name. He’s simply The Mystery Man.

He might only appear for one sequence in David Lynch’s Lost Highway, but The Mystery Man’s enough to leave a crater burned into the film and your brain. As with other Lynchian boogiemen, such as the hobo behind the diner in Mulholland Drive (2001), or the woodsman in search of fire in Twin Peaks: The Return (2017), it’s not what he does that sparks dread… more what he suggests. In his disquieting aura and in his supernatural abilities, we understand he’s not of this world. He apparently can be in two places at once, and knows exactly who you are. He might even be inside your house when you’re not there…

The Mystery Man’s a microcosm of Lynch’s ongoing suggestion that the darkness in the world doesn’t look like a masked maniac or a creature from space… it looks like a mystery, both repulsive and irresistible.

It looks human, it’s invasive, and holds a truth so unbelievable it might fundamentally change who you are. It’s all the anxiety and unanswered questions we ask ourselves alone at night, embodied in one figure. Of course, there’s only so much we’re permitted to know about him, but that’s okay: it’s what we don’t know that’s most terrifying.

The horror genre has produced many of my favourite films. Thing is, I rarely find them frightening. I can certainly appreciate the technical prowess involved in well-crafted scare-fare. Sure, I can be effectively absorbed by atmospherics, seduced by stylised milieu. But, in what many find unsettling, I often find beauty. I’m exhilarated by well-executed psychological thrillers and straight-up horror movies.

As an adult, there’s just a handful of times I can remember feeling the emotion of fear, or a genuine bone-deep chill… and so, emerging from a dark corner of my memory is the unblinking stare over the rim of a ventilator mask. A word beginning with ‘F’ comes to mind. Yep, that f-word, but also a name… Frank. Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper), the blustering, truly unhinged psycho from David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986).

Plenty of pop-psychology has been espoused about this terrifying manifestation of psychosis. Apparently, ‘frank psychosis’ is a clinical term denoting when a person is clearly insane or delusional due to their erratic movement or speech pattern. Often triggered, or exacerbated, by substance abuse. Basically, Frank the psycho ticks all the boxes as a ‘frank psychopath’.

Frank represents all that is sick in society. He’s dangerously confused and plays on every fear of inadequacy that any one of us may have felt. But Frank blows them out of all proportions into a grotesque caricature of oedipal rage. Yet, his uninhibited confidence to be his unapologetic self is seductive enough to court an entourage of equally deranged cronies. He’s an eruption of all our negative emotions, truly a monster from the id. And yet, he’s just a man, a small-town hoodlum of little consequence… unless you happen to meet him.

Like all good fairy tales, Blue Velvet is about transition. It’s the coming of age story of Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan), whose innocence is edged with a darker fascination we all share. He has glimpsed the darker fringes of another world that had been hidden from him and his morbid curiosity leads him deeper into that darkness. He gets so much more than he bargained for! And, so do we…

When Frank abducts Jeffery for a wild ride into hell via “pussy heaven” we are there with them. The use of language, the mundanity of the people and places, only adds to the frightening reflection of a twisted reality conjured by Lynch. It’s a heady cocktail of lowlife criminals, liminal culture, psycho-sexual sadism, drug-use and 1960s ballads.

Frank deeply inhales his gas of choice (Lynch wrote it as helium, Hopper requested amyl nitrite), Jeffrey is bundled out of the car and restrained by misfit henchmen. The sense of imminent, life-threatening danger is undeniable. Frank smears lipstick around his mouth in a sick parody of clown or whore and forcible kisses Jeffrey, delivering a barrage of blasphemies into Jeffreys face. A confusion of language that mixes sex and violence with love and death. He mouths along to Roy Oberson’s “In Dreams”. Oh my, this doesn’t look good for poor young Jeffrey… Our descent into insanity is complete and we know that we will be forever together in dreams, in dreeeeaamms…

When I first saw this scene in the cinema, it took my breath away. My heart rate quickened and I felt the nausea of increased adrenaline in the pit of my stomach – I think the only time a film has triggered the ‘fight or flight’ response. I was too fascinated to do either. Was that my coming of age?

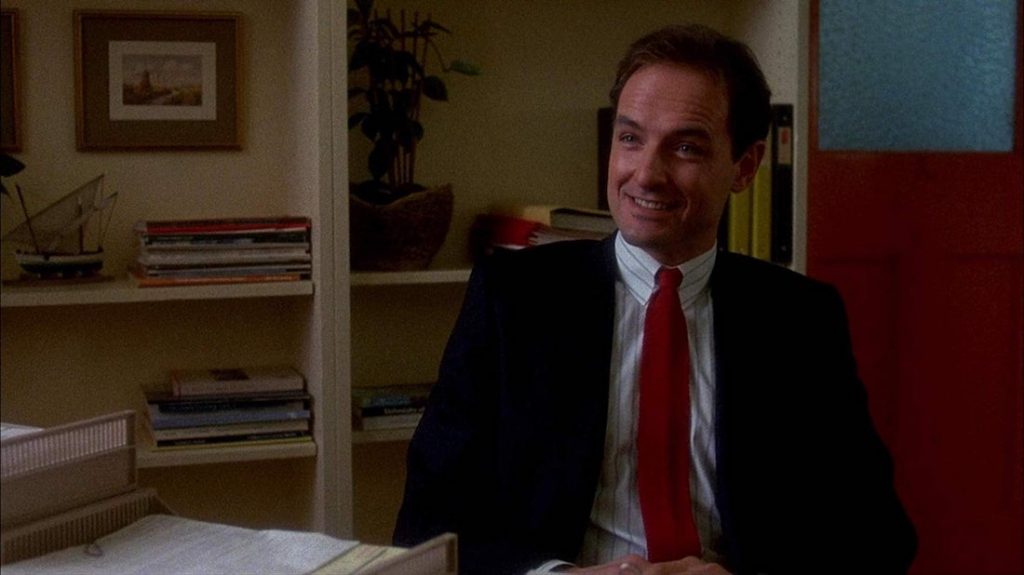

With so many horror icons, audience curiosity leads to endless franchises expanding backstory and motivations. We want to explore the truth that separates the boogiemen from the ordinary men. Terry O’Quinn plays a seemingly ordinary man in The Stepfather as the eponymous lead, but it’s that creeping push for identity that triggers an intensely murderous rage.

Opening with the perfect tonal setter as family man Henry Morrison (O’Quinn) performs his humdrum morning routine amidst a gory suburban crime-scene in the search for another, better family, we’re met with a uniquely human monster. He romances the forlorn mother, relates tough childhoods with the kids, and fills that absent paternal role far too perfectly. Like most serial killers, normal life’s one big performance and if his “co-stars: aren’t up to the act they get mercilessly removed from the picture. What elevates The Stepfather from lesser domestic psychodramas is O’Quinn’s commanding and endearing multitude of performances. He creates a sadistic but broken man desperately pursuing genuine happiness.

In one of the most shocking and disturbing moments, Henry loses his cool and trips over his own web of deceit, retreating inside himself to ask “who am I now?” He goes by Henry Morrison, Jerry Blake, Bill Hodgkins (and more in the decent 1992 sequel), but O’Quinn’s perfection in subtleties capture that absence of identity between the personas. This conflict nails the element of scariest character because it creates a tragedy amidst the horror; that the killer is resisting carnage just as much as his unsuspecting victims.

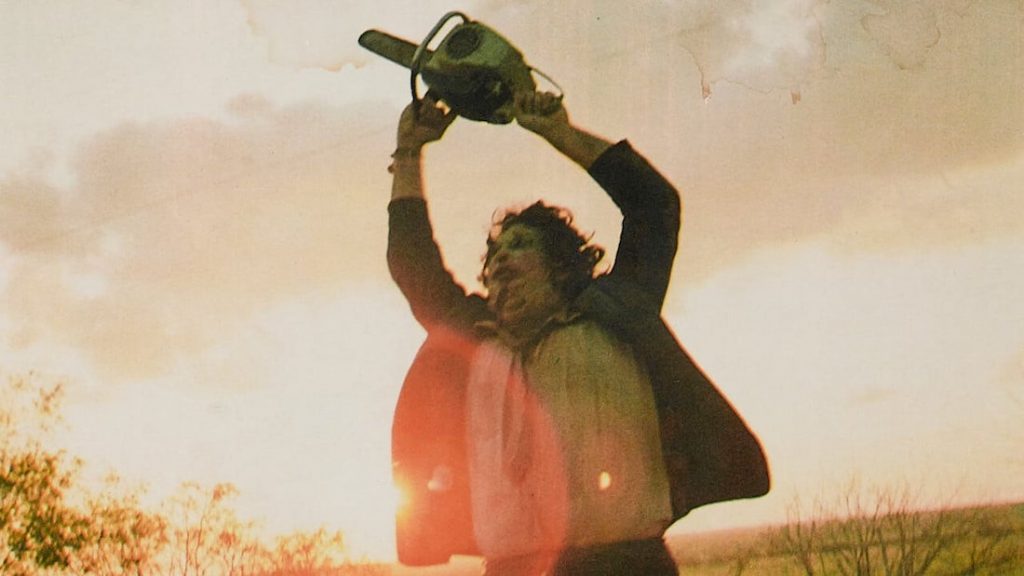

The horror villain who’s haunted me most is, without a doubt, Leatherface from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre movies. Despite the sequels and reboots turning him into a caricature of pure evil, the scariest thing about him in the original 1974 film was how he’s not superhuman or soulless. There’s a person behind the mask, who loves his family. The most chilling moment of Tobe Hooper’s classic is the reveal that Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) isn’t just a psycho lurking in the middle of nowhere, but a younger brother and son and grandson who dresses in an apron to serve dinner and still bickers with his siblings! There’s no supernatural curse at work here; just a damaged human being who isn’t killing for pleasure but is doing his job to put food on the table for his relatives each night. The fact the original film never veers from stark, sweaty realism makes him all the more terrifying.

Of course, the scariest thing is that Leatherface isn’t tough or unfeeling: he’s a big baby who just happens to be wielding a weapon designed to slice through tree trunks. During the famous dinner sequence of Hooper’s film, he’s constantly belittled and shown to be at the mercy of his family who hit and berate him. Throughout the second half of Texas Chain Saw it’s clear he’s not only mentally unstable but also mentally deficient, a hulking man with the intelligence of a child and a fear of the outside world. There’s something altogether more unsettling about a killer who does it out of fear and confusion instead of bloodlust; a grown man with a five-year-old’s brain and a mask made of human skin. Give me all your Michael Myers curses and never-ending Jason Voorhees resurrections, nothing will ever be as viscerally scary as the gritty real-life terror of Leatherface.

“Hi, I’m Chucky. Wanna play?” Don’t be deceived by this character’s large blue eyes and adorable denim overalls. With the addition of freckled cheeks and red hair, it was hard to imagine this toy as the embodiment of evil. Possessed by the spirit of serial killer Charles Lee Ray (Brad Dourif), the doll unleashed a bloodbath in the horror flick Child’s Play (1988). When my oldest sibling first introduced me to Chucky, toys filled every corner of my childhood bedroom. Needless to say, this resulted in numerous sleepless nights of me waiting for my Stay Puft Marshmallow Man to come alive.

Tom Holland (Fright Night) created a haunting atmosphere filled with suspense by following a similar method used by Steven Spielberg in Jaws (1975). The way Chucky feigns lifelessness turns on the TV and causes a gas leak amplifies a sense of dread. While we know from the beginning that the toy is haunted, the director makes us question whether or not the doll is possessed or if it’s Andy’s (Alex Vincent) imagination. Chucky’s humanlike intelligence outwits those around him, eventually causing Karen (Catherine Hicks) to take Andy for a psychoanalyse. It’s not until Andy’s mother picks up the doll’s box and the batteries fall out that Chucky’s chilling secret is revealed. Admittedly, he’s not as intimidating as Jason Vorhees or Leatherface. However, as toys are synonymous with childhood innocence, witnessing Chucky come alive in a murderous fashion is truly haunting.

Personally, I believe this movie’s aged well. Kevin Yagher did a wonderful job creating the red-haired plastic doll, making his movements convincing using animatronics and puppeteering. The effect is realistic and it’s one of the enjoyable slashers where you’re not bombarded with excessive nudity and brutal violence. Although it petrified me as a kid, Chucky’s obnoxious behaviour makes the character simultaneously terrifying and oddly fun. Child’s Play is such a fun ’80s horror and one I frequently revisit.