Rogue Cops and Racketeers: Two Crime Thrillers from Enzo G. Castellari (1976-77)

The Big Racket and The Heroin Busters arrive on Arrow Video Limited Edition Blu-ray box-set.

The Big Racket and The Heroin Busters arrive on Arrow Video Limited Edition Blu-ray box-set.

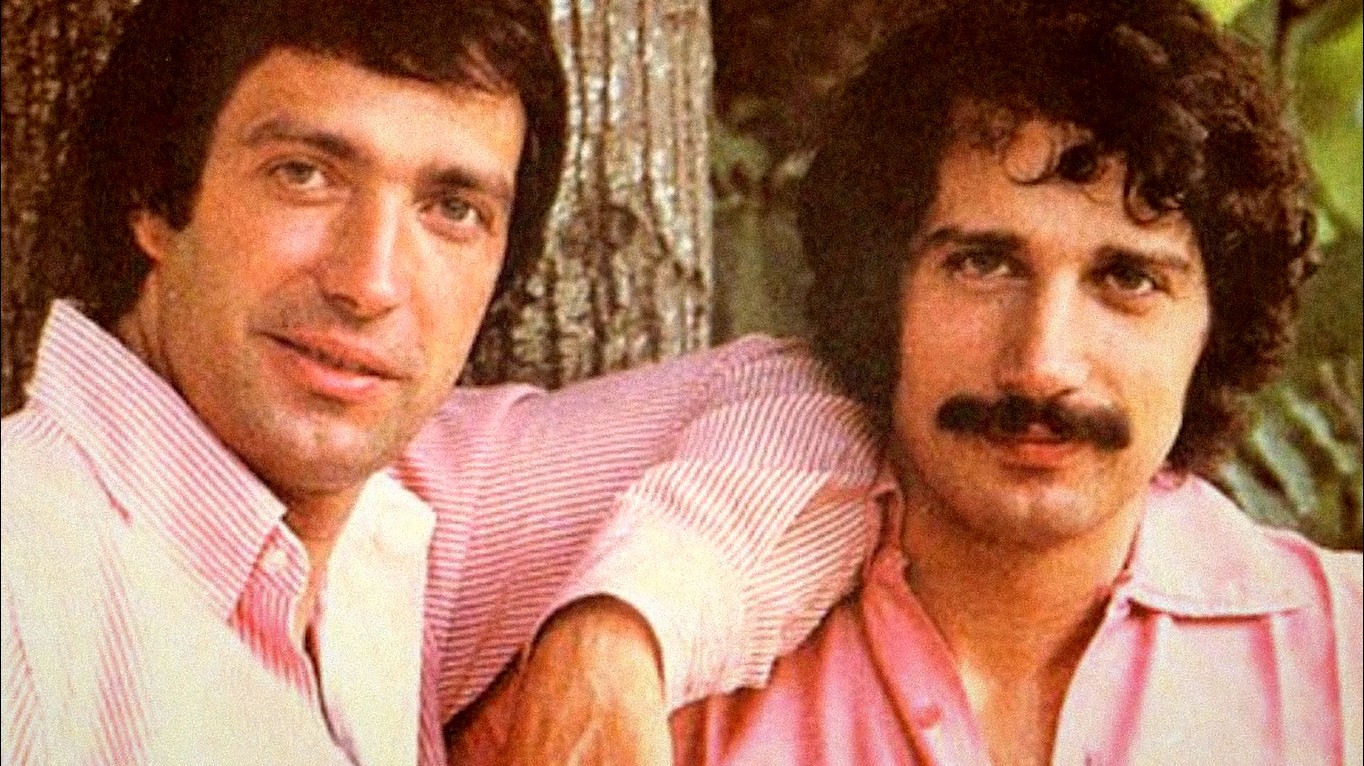

The Big Racket and The Heroin Busters are two superior examples of Italian poliziotteschi, sitting perfectly together in newly restored glory for their Blu-ray debut from Arrow Video, complete with attractive bonus material. Releasing them as a double-bill makes sense as they have so much in common—not least their director, Enzo G. Castellari, co-writer Massimo De Rita, and an ensemble cast led by Fabio Testi, a formidable filone trinity.

Those who require no explanation of the terms poliziotteschi and filone will be eager to grab this Limited Edition box-set, knowing full well what to expect: slick crime thrillers with brutal cops and sadistic criminals. They were shockingly gritty and transgressive back in the 1970s, but are now reassuringly retro and brimming with politically incorrect sensibilities, plus a welcome whiff of mature gorgonzola. But, like much Italian pulp cinema of the era, they’re also stylistically bold and, not far beneath their brash surface, sophisticated subtexts can be found.

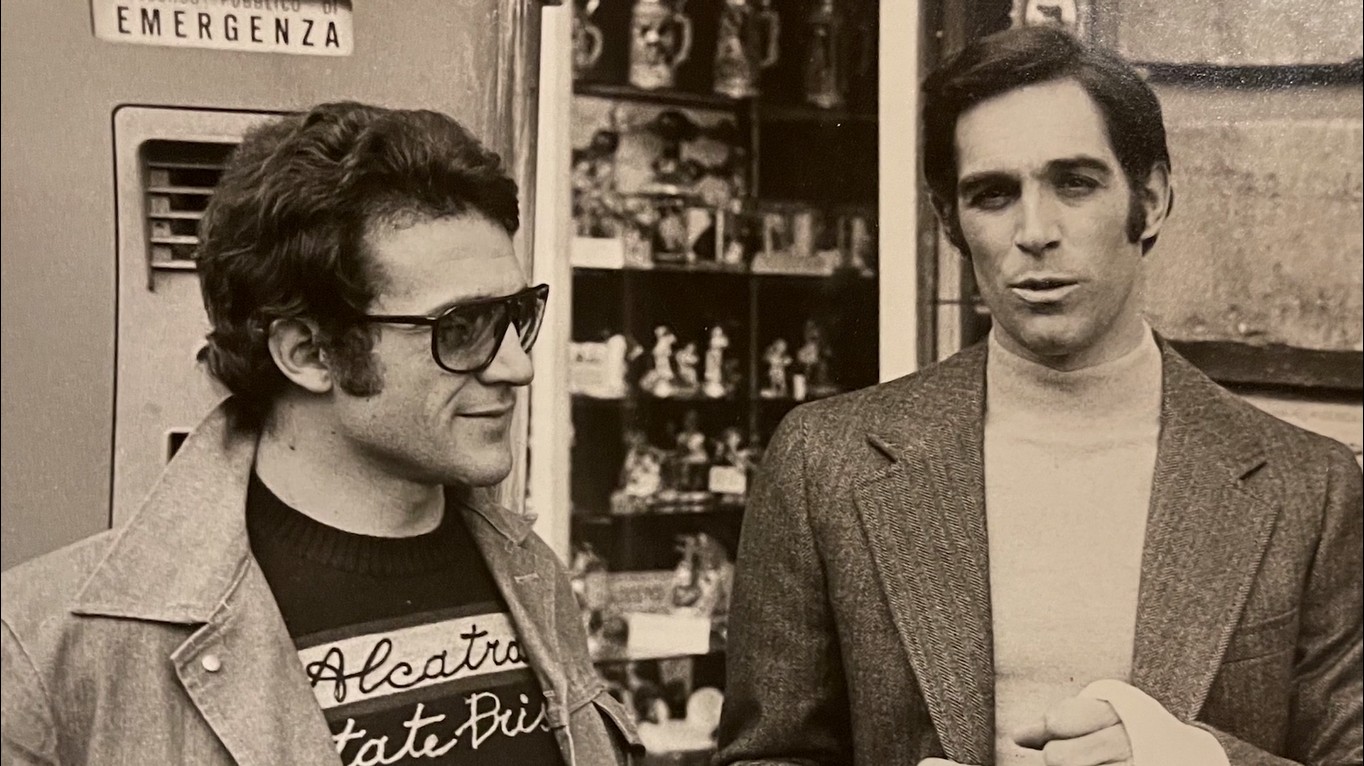

Like his father before him, Enzo Girolami Castellari started his career in sport as a boxer before turning his hand to filmmaking. The Italian film industry ran on a studio system akin to contemporary Hollywood, and was likewise driven by a succession of dominant genres—collectively referred to by the Italian word for bread, filone. Enzo’s father, Marino Girolami, had been making movies since the early-1940s and Enzo often helped on set as he grew up, before becoming assistant director of a handful of his father’s bawdy comedies in the 1960s.

Whilst making A Few Dollars for Django (1966), Marino Girolami deferred his directorial duties to his son. By then, Spaghetti Westerns were dominant and Castellari contributed to at least three more that same year. Demonstrating flair for the genre, he was soon officially in the director’s chair for Payment in Blood (1967), and Any Gun Can Play (1967). He stayed with westerns through the 1960s until the genre grew tired and his career briefly floundered. He tried a war film, Eagles Over London (1969), a giallo-esque crime thriller, Cold Eyes of Fear (1971), plus a few Spaghetti Western send-ups and historical sex romps. But it was with Italian police thriller High Crime / La Polizia Incrimina la Legge Assolve (1973) that Castellari joined the vanguard of directors defining the poliziottescho, which would dominate the Italian cinema of the 1970s, alongside the giallo.

Giallo have recently enjoyed a resurgence in popularity with a run of restored and re-released classics so, perhaps the time is right for poliziotteschi to be rediscovered by a new generation of Italian pulp cinema enthusiasts. These two accomplished examples from Enzo G. Castellari would be an ideal place to start.

A cop battles hoodlums terrorising a sleepy Italian village and extorting cash from the locals.

Italy in the 1970s was rife with varied violence. It was the first decade of a 20-year span known as ‘The Years of Lead’, when riots, kidnapping, bombings, murders, massacres, and assassinations were commonplace. The reasons are, of course, complex, but the violence was mainly due to economic failure and political instability with far-right and far-left factions both escalating the terrorist atrocities.

The cinema responded by offering pure escapism in the form of intellectual art movies and commedie pecorecce (sexploitation comedies) or with ultraviolent thrillers that were part social comment and part wish-fulfilment for those feeling helpless amidst the unrest and everyday threat of random violence. Poliziotteschi fell into the latter category and were hugely popular.

With partisan politics dominating the media, everyone had a radical opinion and any film with a socially relevant theme drew criticism from all sides and The Big Racket was no exception being derided as having either a communist or fascist agenda. So, naturally, it was a box office hit. It tackles contemporary issues by way of broad metaphor and its central message could be summarised by the old adage “evil triumphs when good men do nothing…”

The score by the De Angelis brothers is crucial to setting and maintaining the mood throughout. The duo, who also performed as ‘Oliver Onions’, were hugely prolific and often uncredited due to contractual problems and union rules. They’d already provided the distinctive music for Sergio Martino’s Torso (1973) and two previous films for Castellari: Sting of the West (1972) and High Crime. During the title sequence, to the reverberating strains of their discordant electric guitars, a motley bunch of young bikers assemble outside a store before enthusiastically smashing through the door and totally wrecking the stock within. This is the first in a montage of various business premises being destroyed by brute force or fire as we familiarise ourselves with the faces of the perpetrators.

It turns out that these are the lowest-of-the-low in gangland hierarchy, ‘street trash’ trying to prove their loyalty and ruthlessness and so move up the ranks. The properties that now lay in ruins belonged to those who hadn’t paid up for ‘protection’. We follow the gang doing the rounds as they collect payment from various clients. They’re really a nasty collection of misfits and ne’er-do-wells quickly established with effective bad guy clichés.

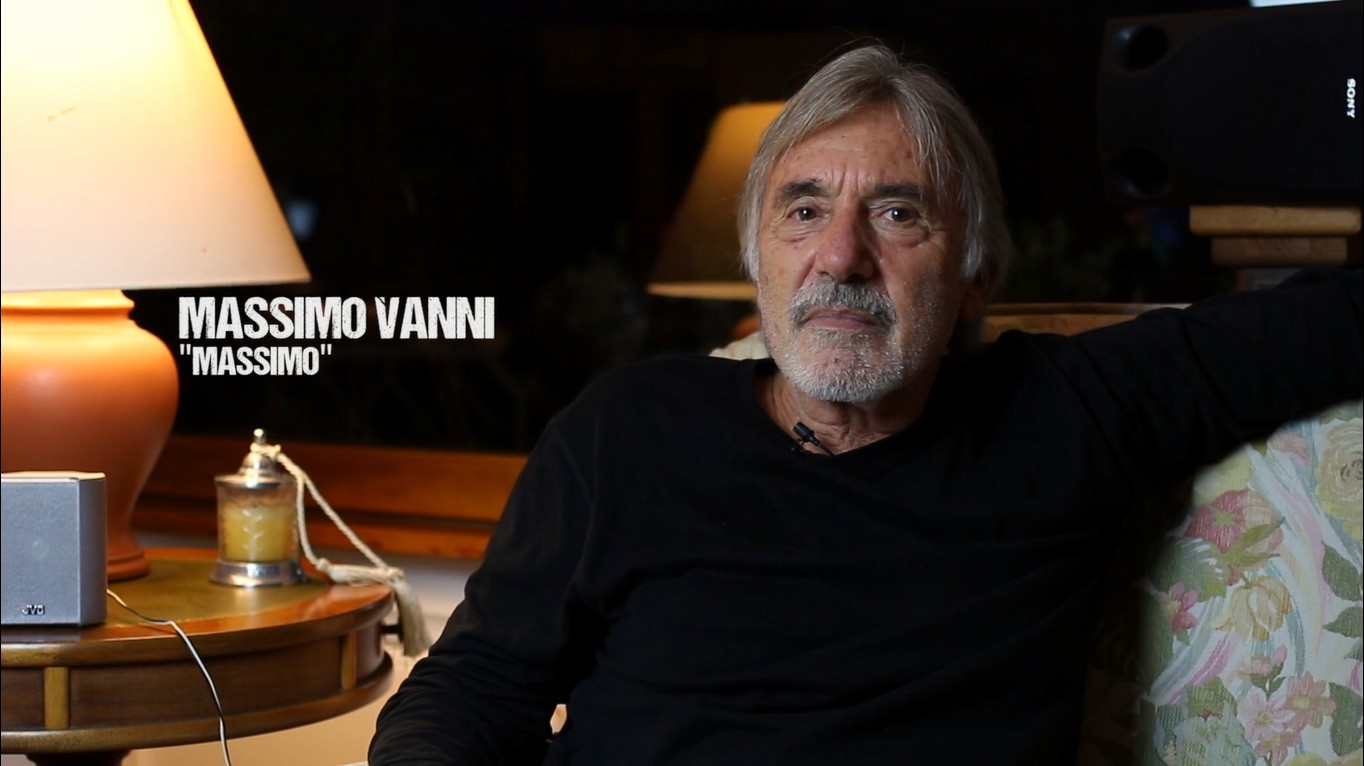

Super-sleaze Gino (Roberto Dell’Acqua) intimidates one shopkeeper by making sexual comments whilst undressing a child’s doll and popping out its eyes. Another henchman (Massimo Vanni) dismays an art gallery proprietor by slashing a moderately erotic painting. The sexualisation of violence intensifies throughout and is one element that may prove contentious to modern sensibilities, but it certainly adds instant ‘creep’ value to the bad guys here.

Their next victim is Luigi (Renzo Palmer), a mild-mannered restaurateur who is unable to produce enough cash. Ox (Giovanni Cianfriglia) roughs him up a little and the gang’s token female, the sadistic Marcy (Marcella Michelangeli), points out that bad things could happen to his teenage daughter, Stefania (Stefania Girolami Goodwin) if he doesn’t find the funds for them.

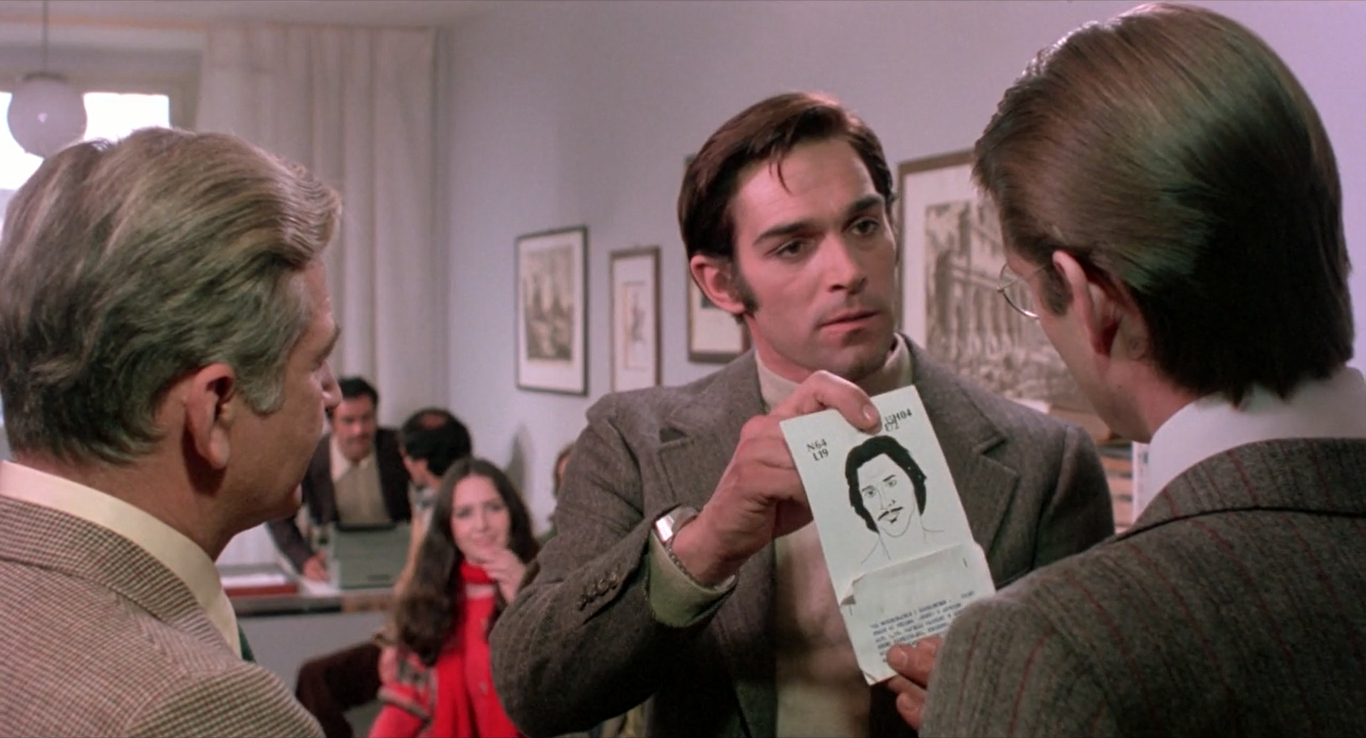

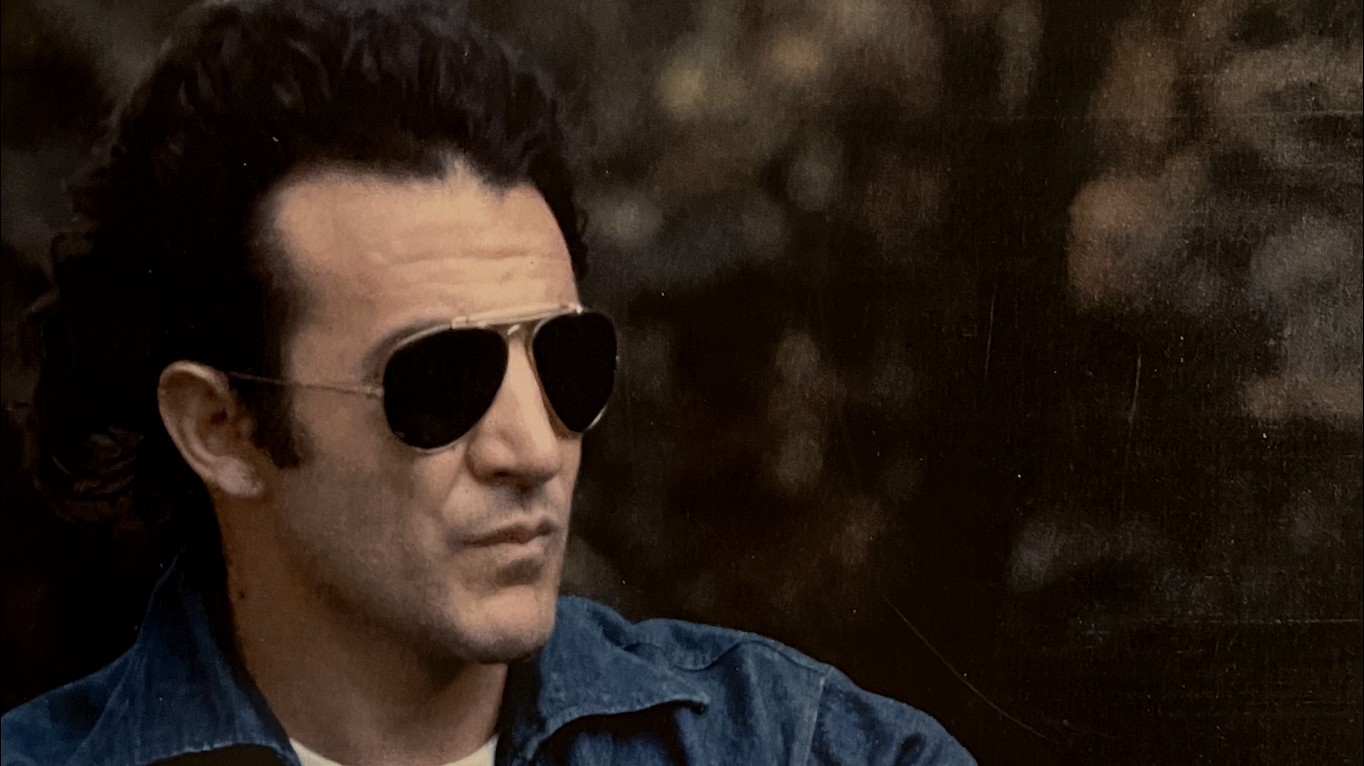

In an attempt to track the money-trail back to the local boss, undercover cop Nico Palmieri (Fabio Testi) follows the gang to their rendezvous with their kingpin, ‘Rudy’ (Joshua Sinclair, credited here as Gianluigi Loffredo), but is spotted. Outnumbered and outgunned, there’s little he can do as his car is rolled off a cliff with him in it.

We’re just 10-minutes in and Enzo G. Castellari has already impressed with some inventive direction, making use of oblique camera angles, shooting through foreground objects, and cleverly using reflections, but it’s this visually arresting stunt that really grabs the audience’s attention. Fabio Testi was a regular in action-driven crime thrillers and westerns, not only for his good-looks, but because he did his own stunts. The camera is fixed in the cab as Testi is thrown about, along with showers of shattered glass and other debris in a disorientating and convincingly dangerous sequence. It’s still difficult to fathom exactly how it was achieved, unless you’re eagle-eyed enough to spot one of the stunt technician’s hands rolling the car along what was presumably a flat and (relatively) safe stretch of terrain—nevertheless, it remains a startlingly inventive, adrenalin-pumping slice of action.

Palmieri’s recovery riffs on the beaten-up hero retraining himself trope that’s familiar from Yojimbo (1961), famously echoed in A Fistful of Dollars (1964), and A Pistol for Ringo (1965)—perhaps it’s Castellari’s Spaghetti Western pedigree showing through? It only takes a few minutes of montage, but clearly time has passed, and the cop is eager to exact vengeance but determined to stay within the law. At least to begin with…

He manages to convince Luigi, the restaurateur, to make an anonymous witness statement and enlists the help of Pepe (Vincent Gardenia), an old-school pick-pocket, to infiltrate the gang in an attempt to get them caught red-handed. The presence of veteran character actor Vincent Gardenia, who played Lieutenant Frank Ochoa in Deathwish (1974), is a clue to how things are about to unfold.

There’s corruption in the police ranks and it’s not long before the gang identify and exact cruel revenge on the informants. Stefania is abducted from her convent school by fake nun, Marcy, before being brutally raped by Gino, and taking her own life. Apparently, this was a difficult scene to shoot—not technically, but emotionally, as Stefania Girolami Goodwin is the director’s own daughter. It’s an effectively harrowing scene that rests on the strength of the actress’s brief performance. During a botched bank heist, the gang convince a crowd of onlookers that Pepe’s nephew is a child-killer and goad the mob into beating him to death. A small group of people profiteering from stoking hatred and manipulating the masses with false information is a metaphor that remains just as pertinent today.

When Palmieri’s loyal police partner, Salvatore (Sal Borgese), is mercilessly gunned down during one of the film’s two exceptionally well-choreographed shoot-outs, set in a train yard, he realises that the gang were once again tipped-off by someone within his department. He wouldn’t have made it out himself if it wasn’t for the timely intervention of Rossetti (Orso Maria Guerrini) an engineer who just happened to be a champion rifleman returning from a clay-pigeon shoot who manages to pick off a good number of the villains. Being a celebrity sportsman, the newspapers recognise him and proclaim him a hero. So, of course, the gang pay him a visit, rape and murder his wife, then torch his apartment. It’s a raw, intense scene that bears striking similarities with the infamous rape in A Clockwork Orange (1971).

The third act blatantly riffs on The Dirty Dozen (1967), but it’s more of a ‘Dirty Half-Dozen’ instead as Palmieri channels his inner Dirty Harry and—you guessed it—goes rogue. He assembles his crew of vengeance-fuelled men who’ve lost someone to the gang—Luigi, Pepe, and Rossetti. He recruits Mazzarelli (Glauco Onorato) the incumbent drug lord displaced by Rudy and his thugs, and also breaks out a notorious mass murder known as ‘The Solo Machinegunner’ (Romano Puppo) from jail. Convinced the law is not capable of dealing with criminality that has already insinuated itself in the higher echelons of the establishment, he intends to beat the gangs at their own lethal game.

The stage is set for a (literally) high octane finale that stands out as one of the genre’s most spectacular and slickly executed. Their plan is to attack a ‘meeting of the clans’ when various gang lords gather in a remote agricultural factory to discuss their unified strategy for carving up Italy into various territories. It’s clear the mob has taken control of major industrial and political figures through extortion, blackmail, or simply mutual greed. The corruption of those entrusted with positions of power is a recurring theme of the genre and the scenario here reflects how post-war Italy was divided into various Mafia-controlled precincts after the fall of the Mussolini regime. As the mysterious overlord explains to the gathering of gangsters, “politicians want chaos too, people’s insecurities benefit them,” effectively outlining what we now call ‘disaster capitalism’.

ITALY | 1976 | 101 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN

A cop goes undercover to break up an international heroin smuggling ring and butts heads with a hot-tempered Interpol agent assigned by his agency to do the same task.

This film wastes no time establishing its premise, as scenes of neon-lit night streets are intercut with details of junkies preparing and injecting their heroin fixes, all set to 1970s-style histrionic guitars and thumping rhythms, courtesy of prog-rockers Goblin who provide the score. Like the De Angelis brothers, they too were responsible for the distinctive identity of many Italian genre films, indelibly associated with Dario Argento’s Profondo Rosso (1975) and Suspiria (1977).

The opening 10-minutes are a sequence of seemingly incongruous locations around the globe. In Columbia, a man swiftly makes his escape over a hotel roof when military police appear at the poolside; in Amsterdam, a man is set upon by a group of thugs, watched over by an armed stranger in a check coat; in Hong Kong, a denim clad man picks up a parcel of powders from a fisherman on the harbour wharf; in New York, a businessman phones Rome to go over import-export plans for pharmaceuticals; and in Rome we meet Mike Hamilton (David Hemmings) an Interpol agent whose presence is, “far from official.” He’s set up an elaborate operation to tail a suspected drug ‘mule’ when they arrive at the airport, but his plan is confounded by an extra vigilant drug sniffing dog and the target, Fabio (Fabio Testi), the man in denim from Hong Kong, is arrested there and then.

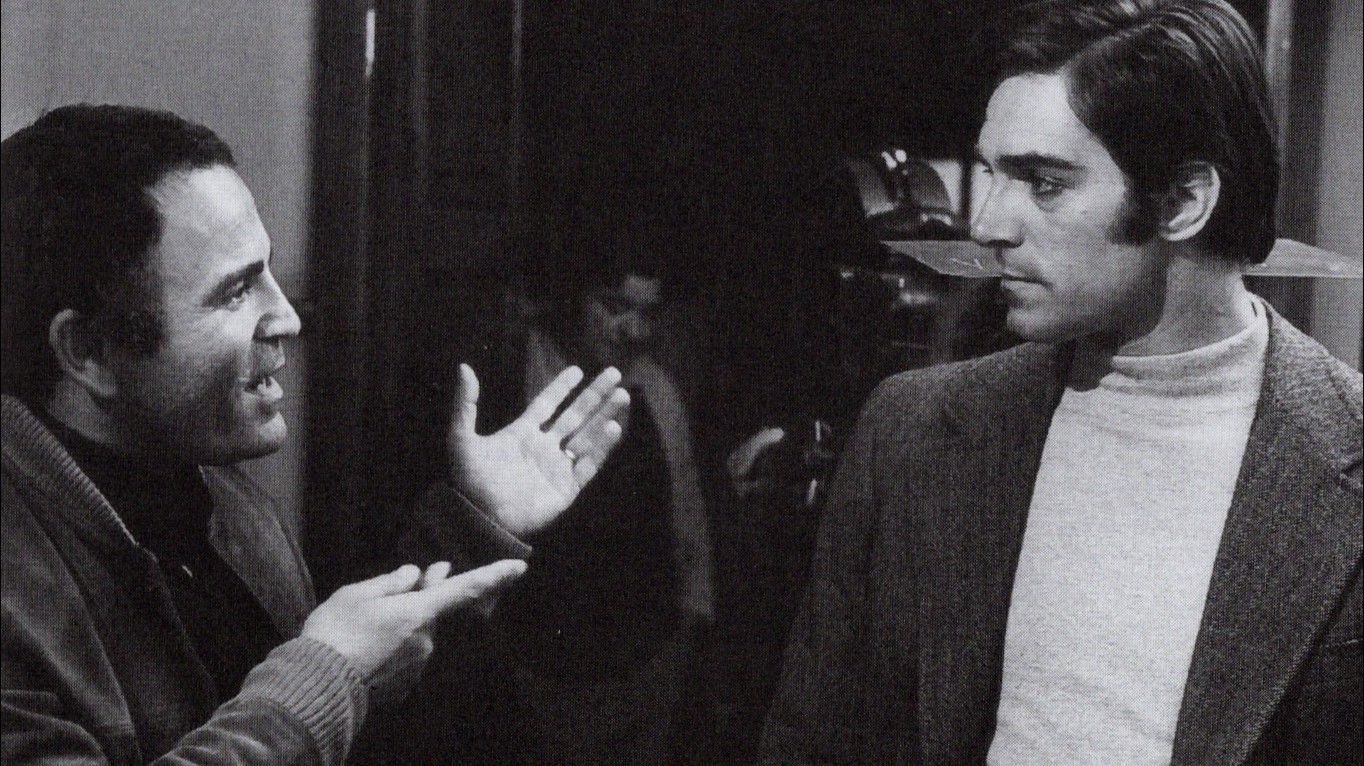

Casting David Hemmings in the joint lead was a shrewd move as the star had box-office draw at home and abroad. He was popular with the more high-brow Italian audience after his appearance in Michelangelo Antonioni’s slow-burn psychological thriller Blow Up (1966) and had a huge hit with Dario Argento’s classic Deep Red / Profondo Rosso (1974), which had rekindled the appeal of giallo. Fabio Testi was well known in Italy for a handful of westerns and had rose to prominence in Massimo Dallamano’s giallo What Have You Done to Solange (1972).

The Italian title translates as ‘The Drug Route’, which is a better fit as it’s not only heroin that’s involved, but is also a cleverer title as it covers a range of individuals at different stages along their personal ‘drug routes’. The film follows a similar template to The Big Racket as we follow the gang of drug dealers—some played by the same set of actors—as they deliver to street pushers and intimidate junkies for ever-increasing payments, coercing them to convert new users and expand the market. Sure, there’s a collection of the typical cinematic drug addled low-lifers, but also a few less stereotypical examples such as the middle-class mother who buys heroin for her addicted daughter, telling her “you’re so beautiful when you’re not screaming.”

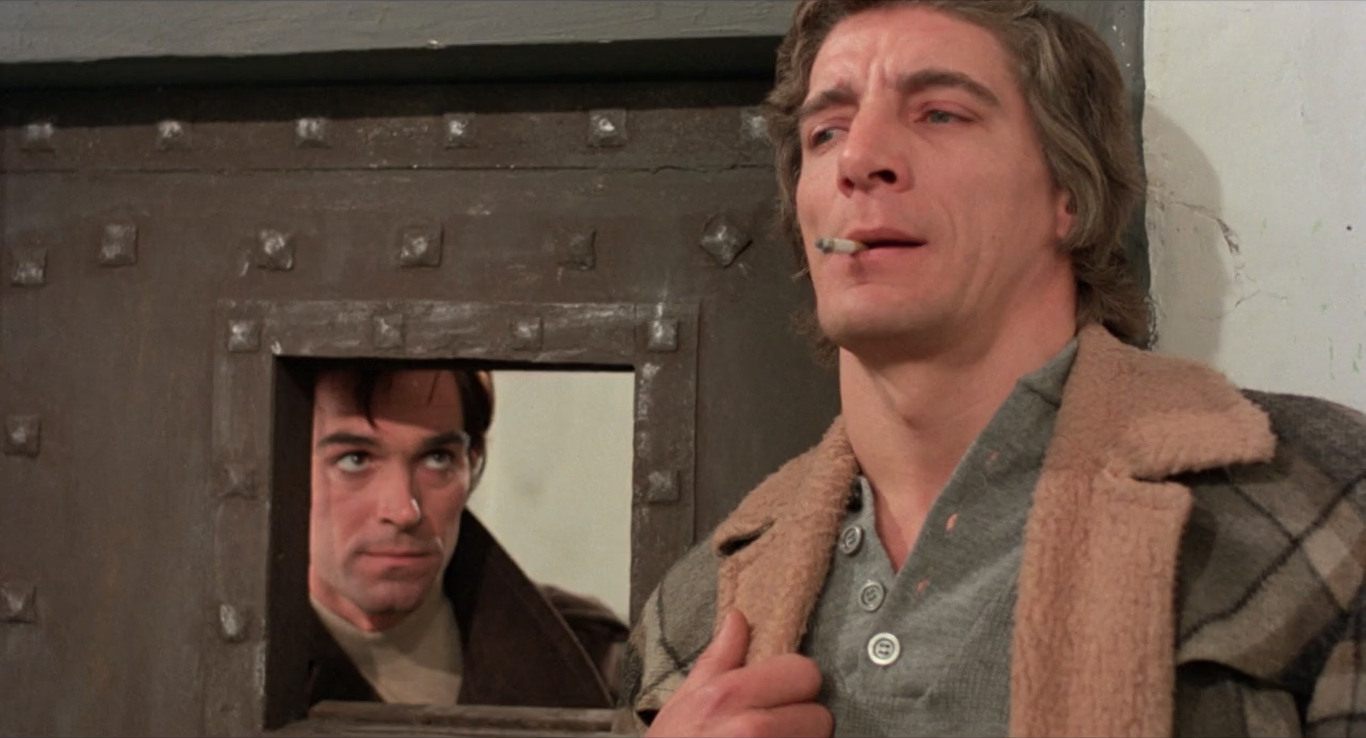

Gilo (Wolfango Soldati) is a desperate junky caught pushing to school kids and ends up in the same holding cell as Fabio where he completely goes to pieces, puking and pissing himself. Fabio takes pity and shares his stash, hidden in the heel of his shoe. Together they hatch an escape plan on the condition that he introduce Fabio to the Rome cartel, which he intends to take control of. They hide out in the apartment of Vera (Sherry Buchanan), Gilo’s girlfriend who acts in porn movies and sometimes takes private clients to fund their shared habit.

With Fabio’s tutelage, they begin to work their way up in the drug gang and eventually catch the attention of the local kingpin, ‘Gianni’ (it’s Joshua Sinclair, again, and still credited as Gianluigi Loffredo). Fabio meets him on the film set in the porn studios and Castellari exploits the dramatic lighting opportunities, also setting up a nice foreshadowing for the eventual demise of the villain on the stage of a Roman theatre.

There’s also a beautifully choregraphed and intercut parallel death scene involving two linked characters. One is double-crossed and left to face police during a bungled jewellery shop heist, to die in slow-motion. The other fades away in a pale haze after injecting a deadly dose of uncut ‘something’ intentionally supplied to silence them. A bloody, brutal end and a peaceful passing. Both just as dead, victims of the illegal drug racket.

If The Big Racket was a metaphor for the domestic troubles afflicting Italy, then The Heroin Busters is a critique of foreign policy and how global economies affect each other. Much of the drug trade we see here is funded by Americans, exploiting less affluent countries, and using Italy as a gateway between east and west—just as it has been ever since the opening of those trade routes during the Renaissance. The drugs come in and disrupt Italian society, fuelling street-level and corporate crime, yet the profits are syphoned off to the US, who are vying to dominate world trade.

If anything, The Heroin Busters is a little lighter in tone than The Big Racket, in no small part due to the lively rapport between Hemmings and Testi, and follows a more familiar formula. It could easily have been made as a Spaghetti Western, if cars were swapped for horse and stagecoaches, and the trade was in guns and stolen bullion instead of drugs. There’s a great set piece involving a stand-off in a derelict spaghetti factory that’s staged like a wild west shoot-out. Throughout, Castellari uses the cinematic stylings of his spaghetti westerns, too, with deep focus taking in distant figures and extreme close-ups in a single frame. There are also plenty of his trademark shots through foreground objects. keeping things always visually interesting.

In the several superbly planned chase sequences his dynamic, high-impact approach is at the fore and again he makes the most of Testi’s stunt prowess. However, this gets the better of them both in the final reel. Testi was also a trained and licensed pilot and they couldn’t resist a somewhat leisurely plane pursuit that goes on far too long. Despite some nice miniature work, scheduling constraints meant that Castellari couldn’t get all the footage he needed. The anti-climatic sky chase ends up being an incongruous add-on, especially as it follows a particularly gripping, fast-paced chase through an underground construction site.

ITALY | 1977 | 94 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN

director: Enzo G. Castellari.

writers: Enzo G. Castellari (story by Dino Maiuri & Massimo De Rita) (Racket) • Enzo G. Casrellari (story by Galliano Juso & Massimo De Rita) (Heroine)

starring: Fabio Testi • Vincent Gardenia & Renzo Palmer (Racket) • David Hemmings & Sherry Buchanan (Heroine).