PERFECT BLUE (1997)

A pop singer gives up her career to become an actress, but slowly goes insane when she starts being stalked by an obsessed fan...

A pop singer gives up her career to become an actress, but slowly goes insane when she starts being stalked by an obsessed fan...

The 1990s were a revolutionary decade for the cinema of Japan that saw cyberpunk, J-Horror, and anime break into global markets. Katsuhiro Ôtomo’s Akira (1988) heralded this international interest, and its importance and influence as a vanguard of an anime new wave cannot be overstated. I still recall its UK big-screen début at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) and the buzz that followed. Back then, feature-length anime only screened in arts cinemas but quickly garnered a cult following among those who were surprised by the quality of the storytelling, the beauty of the art, and perhaps shocked by the mature content.

They certainly weren’t typical ‘cartoons’ and rewarded viewer engagement just as much, if not more than, any mainstream thrillers and genre fare. Now, more than three decades later, they are bigger than ever, with the Demon Slayer movie Kimetsu no Yaiba / Infinity Castle (2025) breaking US box office records, followed a month later by Chainsaw Man: Reze Arc (2025), which also débuted in the No.1 slot.

That cult following has well and truly exploded into the mainstream. Thus, this year’s theatrical re-release of Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue was timely and rekindled interest in this essential anime. Alas, it did not come to a cinema near me, but that’s not a problem because Anime Limited are also releasing the spotless restoration in a splendid 4K Ultra HD and Blu-ray Deluxe Edition with all the trimmings. So, let us briefly look back on how we got to this landmark release and consider some aspects of its lasting appeal.

After the positive reception of his 1984 short manga Toriko, Satoshi Kon came to the attention of Katsuhiro Ôtomo, who hired him as an assistant on his seminal Akira manga series from the mid-1980s and into the 1990s. Though he’s not credited with direct involvement with the 1988 anime feature, their collaborations continued, and he scripted Ôtomo’s live-action film World Apartment Horror (1991), also adapting the film as a manga. His own breakthrough into anime came when he and Katsuhiro Ôtomo co-directed three episodes of the first season of fan favourite JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure (1993–2002). Around the same time, Satoshi Kon collaborated with Koji Morimoto on the writing and animation for “Magnetic Rose”, the opening segment for the anthology Memories (1995), which was produced by Katsuhiro Ôtomo.

The novel Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis / パーフェクト・ブルー 完全変態 by Yoshikazu Takeuchi was first published in 1991 and promptly adapted into a script by the author. There was some interest in producing this live-action treatment, but funding never quite materialised, and the screenplay found its way into Satoshi Kon’s hands with a view to making it into an anime instead. Apparently, he was not captivated by the treatment and, without reading the original novel, he worked with scriptwriter Sadayuki Murai on a major overhaul that retained the title, central themes, and main characters, but changed so much of everything else that it was no longer considered an adaptation.

After a scene that could be from any number of generic anime series, featuring three colour-coded ‘Powertron’ rangers in clinging jump suits and helmets, we find ourselves at some sort of well-attended anime convention and drop into a narrative that’s already well underway. We know from the posters displayed as background details that the main attraction is the J-Pop trio CHAM! Dressed in typically doll-like attire, short skirt and baby pink frills, Mima Kirigoe (voiced by Junko Iwao), introduces the final number with the announcement that it will be their last song together, explaining that she is graduating from the idol group. She implores the fans to continue their support for CHAM! as well as following her new career as an actress.

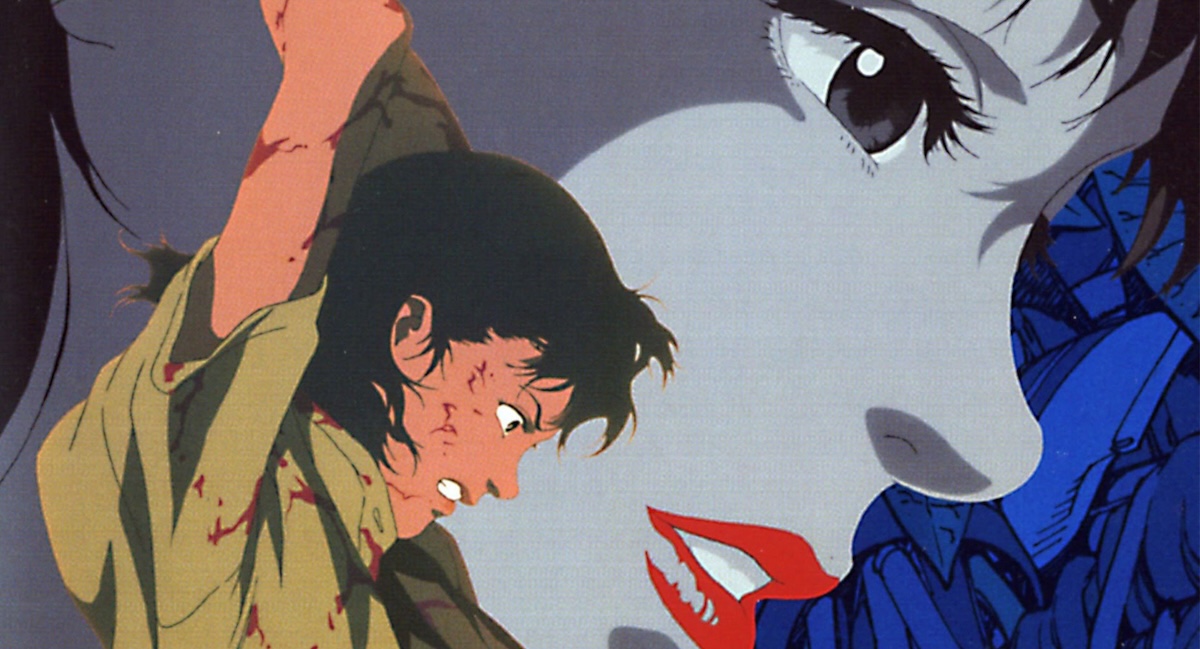

What at first could easily be taken for the opening of a mahō shōjo (magical girl) anime is immediately subverted by some bloody brutality as a bunch of hecklers try to disrupt the gig, and one of the security personnel, Mamoru Uchida (voiced by Masaaki Ōkura) intervenes, taking several punches without retaliation. There’s something about his ghoulish looks and dead-eyed stare that intimidates his attackers and effectively diffuses the situation.

Rumi Hidaka (voiced by Rica Matsumoto), who manages CHAM!, already has some minor television roles lined up for Mima. Though it’s not long before the producers are floating the idea of expanding her role with some decidedly raunchy scenes to capitalise on her sweet and innocent stage persona. What they ask of her escalates and, despite protest from Rumi, she agrees to an explicit rape scene in the serial killer crime series Double Bind to prove her acting chops and conclusively shed her idol image. Meanwhile, there is unrest in the fan community, with some accusing her of betraying her former bandmates, and this comes to a head when television producer Tadokoro (voiced by Shinpachi Tsuji) opens some fan mail addressed to Mima and is injured by a letter bomb.

Around the same time, news reaches Mima that one of the hecklers at her final CHAM! show is critically injured in a hit-and-run. On top of this, she begins glimpsing things that may not be quite real, such as her former-Idol self in mirrors and train window reflections. Mima’s voice sounds like a cutesy anime character when she is playing the part of her kawaii-costumed character but becomes more naturalistic as the film progresses and she takes on adult roles, literally finding her voice. Or could she be further losing herself within another constructed personality? She also sees Uchida in the background among crowds of onlookers during location shoots. Her grasp of reality seems to be eroding as she tries to leave one version of herself behind by taking acting roles in which she becomes someone else.

The celebrity that starts to believe the hype may be a well-worn stereotype, but how many of us are truly honest with ourselves, even when alone and without the pressure of fan expectations? When one is thinking, those thoughts are often formulated as words and imagined as a voice. So, who does that voice belong to and to whom is it speaking? This fractal structure of self is not too far removed from the fractured perceptions that Perfect Blue explores, which is why it remains relatable and why the elements of psychological horror resonate deeply within us.

Rumi decides that Mima needs to be online and brings a new thing known as a personal computer to her apartment, signing her up for online services and explaining the concepts of emails, websites, and fan forums. Yes, this was all cutting edge at the time. YouTube, which would explode the idol scene internationally, would not launch till eight years later, in 2005, with Japan’s equivalent, Nico Nico Douga, following in 2006 – the same year that Twitter was released for public use. So, the plot prominence given to internet influence and those who would one day be known as influencers is highly prescient.

Mima is morbidly fascinated, flattered and unnerved in equal measure by the “Mima’s Room” homepage, a fan-run site that shares intimate knowledge about her everyday activities. It not only reports on her whereabouts while filming, but where she goes shopping and tiny details such as which foot she led with as she stepped off the metro. She can’t understand how anyone can know such things and realises that the information must come from someone close to her or be the product of an assiduous stalker. The moderator of the site, who uses the handle ‘Mi-Mania’, a play on her idol name, claims that the ‘Real Mima’ emails daily updates with the information, differentiating her from ‘Actress Mima’, which the site implies is some sort of imposter. We are given a piece of the puzzle that Mima does not have when we see Uchida keying in the homepage content, with a glowing, angelic version of Mima leaning over his shoulder to read those emails aloud.

As we shift further from the era’s expectations of an animated movie, Shibuya (voiced by Yoku Shioya), the writer of Double Bind, is viciously murdered in a sequence worthy of any self-respecting giallo. Mima either imagines or dreams—maybe remembers—the details of this as if she witnessed it.

Creating a public persona is something most, to some extent all, celebrities do. In fact, don’t we all? Most of us assume subtly different personalities to suit different situations. For example, we may talk with our parents differently than we talk with our friends and may behave entirely differently in the company of close friends than with professional colleagues. How closely does our self-image match with how others think of us? If we are honest, we acknowledge there is a rift between those perceptions, so how much wider must that gap be for those in the spotlight of stardom?

Wanting to be something gets in the way of being oneself. This is never more tragically apparent than in careers that rely on youthful beauty or sporting prowess. Internally, we may still feel as we did in our youth; we may still have the same dreams and aspirations. Maybe we even achieved them. But holding on to them may not be so easy.

Some of us welcome the changes life brings us; we mature and celebrate our increasing knowledge and experiences, the friends and family we have made. Others, though, may focus on what is lost. They may grieve the passing of youth, the loss of family and friends; their experiences may no longer seem as sweet and they may become bitter, resentful of others who achieve what they wanted or even once had. This profound emotional territory is explored by one of Perfect Blue’s core narrative threads.

Perhaps because I recently revisited the work of Takashi Ishii, I was reminded very much of his assured akai thriller Angel Guts: Red Flash (1994), which I believe must have exerted its influence upon Perfect Blue and with which there are striking narrative parallels. This isn’t surprising as both Takashi Ishii and Satoshi Kon were instrumental in changing the trajectory of manga to appeal to mature readers, and the clean graphic aesthetic can be detected in their filmmaking.

I have seen both films dismissed as exploitation. Although they thematically explore various aspects of exploitation, I disagree that they fall into that category themselves, especially given their astute socio-political relevance, stylistic flourishes, and underlying intelligence. Storytelling conventions of manga had been informing Japan’s distinctive cinema since the 1960s, and this is never more apparent than in Perfect Blue because its illustrative visual identity is directly manga-informed. It may appear a little basic when compared with today’s top-tier anime, and some details such as faces are simplified, or absent in the case of the background ‘extras’ in street scenes. However, these faceless cut-outs add to the sense of mass anonymity where individuality is swamped and the city becomes impersonal. Also, this is following an established manga convention, and such stylistic choices are part of what makes it vitally relevant to understanding the evolution of both manga and anime.

I saw it many years ago on a worn-out rental VHS and remember I was very impressed though came away baffled by its ambiguous and surreal climax. Either I simply wasn’t paying attention back then, or the clarity of this beautiful new print allows deeper and direct engagement, because the intricate plot is superbly mapped out and everything falls into logical place during the final act, making perfect sense of all that happened.

It’s one of the tightest plots of any psychological thriller and can easily stand alongside such classics as Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), Sergio Martino’s The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (1971), or Dario Argento’s Tenebrae (1982)—all three of which also deal with similar rifts between private and public personae of central characters. And, yes, from Mima’s perspective that we share, there is a disjoint in reality, but there’s no loose end that cannot be explained once we learn who has been manipulating things behind the scenes, influencing fans and fellow performers by exploiting their monomania and paranoia to divert and ultimately pervert their desires. The finale is a spectacular chase across the rooftops and through the alleys of Tokyo as two characters fight for their sanity and grip on consensus reality. The outcome will rest on who has the strongest will and sense of self.

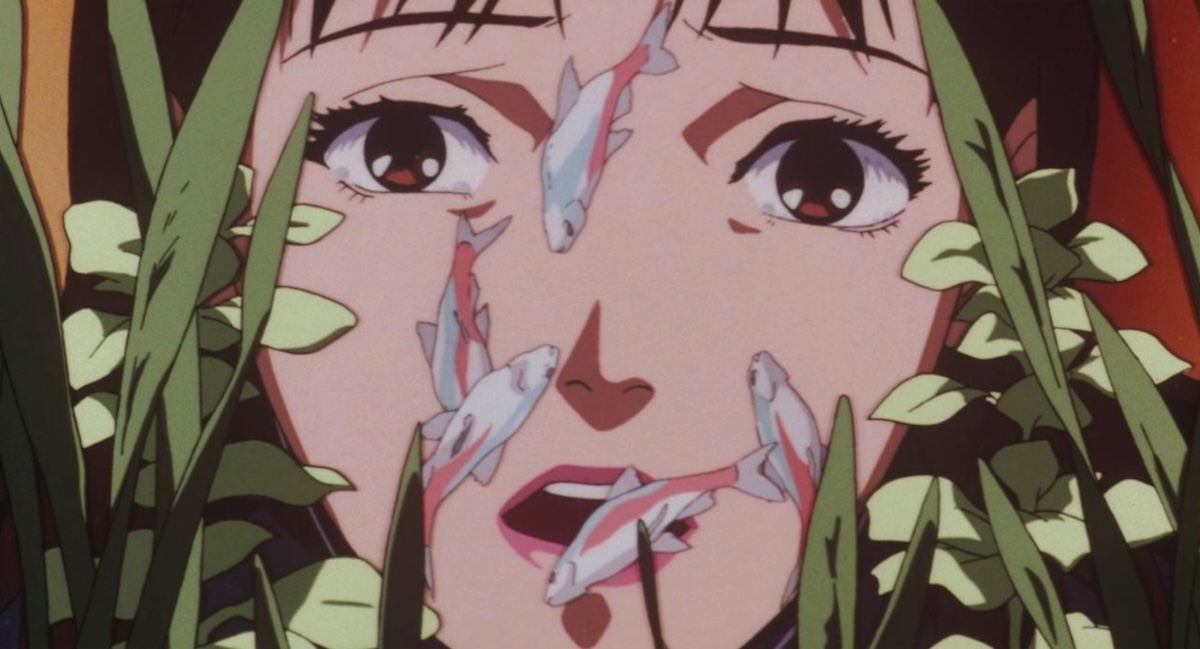

The use of urban settings throughout is a deliberate deployment of environment as an externalisation of psyche. Satoshi Kon chose to avoid the fantastical settings that anime was beginning to rely upon and grounded Perfect Blue in contemporary Tokyo, keeping things relatable while gradually influencing viewer responses to familiar, everyday spaces that become uncanny and dangerous. Mima’s apartment is a great example, as her ‘safe space’ is surveilled by an initially unidentified stalker and becomes increasingly sinister as she notices incongruities and subtle, unexplained changes: fish seem to return from the dead; a poster she remembers removing is back on her wall. Is she going mad, or is someone gaslighting her by changing things around while she is sleeping or absent? The final explanation of this strangeness is another example of Perfect Blue’s narrative elegance.

JAPAN | 1997 | 82 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE • ENGLISH

director: Satoshi Kon.

writer: Sadayuki Murai (based on the novel ‘Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis’ by Yoshikazu Takeuchi).

voices: Junko Iwao, Rica Matsumoto, Shiho Niiyama, Masaaki Okura, Shinpachi Tsuji & Emiko Furukawa.