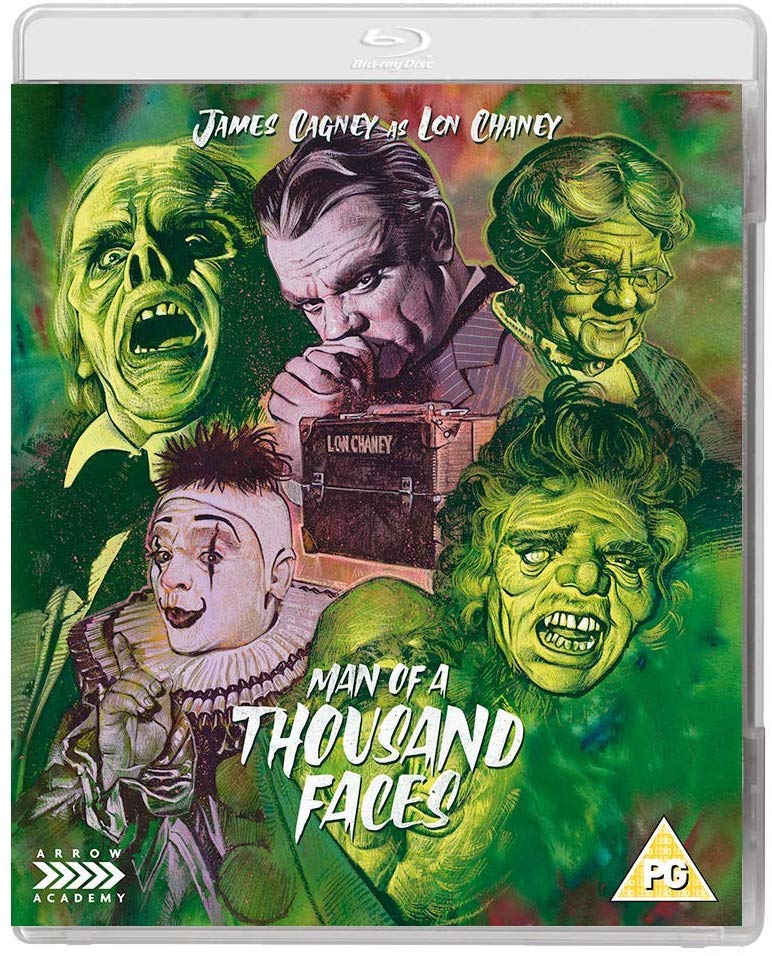

MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES (1957)

The life and career of vaudevillian and silent screen horror star Lon Chaney, including his contentious relationship with his neurotic wife and his premature death.

The life and career of vaudevillian and silent screen horror star Lon Chaney, including his contentious relationship with his neurotic wife and his premature death.

The two audiences Man of a Thousand Faces appeals to are fans of Jimmy Cagney (as this is the most interesting of his later roles) and film buffs (as this is the first time Hollywood produced a biopic about one of their own). Here we have one of the top actors of the ‘talkies’ playing one of the towering talents of the silent age, Lon Chaney.

The two problems Man of a Thousand Faces falls foul of are that biopics are generally predictable (especially if you know something about their subject) and they’re bound by the dominant attitudes of the times they portray, as well as the times in which they were made. Here we have a film that examines the prejudices of the 1910s through the lens of the uptight 1950s. It’s bound to seem very dated when viewed from a distance of 50 years!

An average person today will find its whole tone overly melodramatic and the pacing, at least for the first half, much too slow. I think it qualifies as a ‘potboiler’, a style that had already fallen out of fashion when it was made in 1957. If you can steel yourself and push on through to the mid-point your efforts will be rewarded. Like so many films about the lives of celebrities, it’s almost two films that collide somewhere in the middle: the first half covering the ‘before they were famous’ part of their life, before switching pace when they ‘make it big’ and their fame changes everything.

Considering there was no real template for the Hollywood biopic (which has been done so much better since), Man of a Thousand Faces is a brave and often clever attempt. It was more than a quarter-century after the death of the real Lon Chaney when writer, Ralph Wheelwright, faced the problem of researching a life veiled in mystery. Chaney was also billed as ‘the mystery man’ and never talked about his tumultuous private life. After all, he advised Greta Garbo that she’d be even more successful if she remained enigmatic and refused interviews, an approach that had worked for him!

Wheelwright couldn’t even find confirmation of what year Leonidas Frank Chaney was born… but just because Lon Chaney tried to keep his personal and screen personae separate, that didn’t mean the press of the time respected his privacy. There was plenty to be found about him in the public domain after 1913 when he first attracted public attention due to a scandal that ruined his stage career.

His first wife, Cleva, burst on stage during his act at Los Angeles’ Majestic Theatre and drank poison in front of a shocked audience. Her suicide attempt was not successful, though it did end her successful singing career. The ensuing divorce was, of course, played out in the courts so could be corroborated. So could Lon’s custody battle over their young son, Creighton, who would grow up to be better known as the actor Lon Chaney Jr.

It was this series of unfortunate events that forced Lon to find work in the fledgeling film business that was just establishing itself in Hollywood. He spent his first years taking pretty much any extra work that came his way, and if his looks didn’t match with the casting call he’d use make-up to ensure that they did!

So, Wheelwright’s script tends to focus on these aspects of the actor’s life and uses ‘dramatic license’ to fill in the rest. He showed his story outline to James Cagney on the set of These Wilder Years (1956), which he also wrote. Cagney leapt at the chance to portray one of his screen heroes. With his name attached, Wheelwright touted the script around the studios and ended up with both Paramount and Universal bidding against each other for the rights. The latter offered the most.

Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts had both worked on Cagney’s last great gangster movie, White Heat (1949), and were brought in to expand the story into a screenplay. This might give us a clue about the major failing of Man of a Thousand Faces. White Heat’s director, Raoul Walsh, had advised Cagney to walk away from that film which he felt was an overworked and turgid potboiler. Cagney had instead taken control and re-written the script himself with help from a couple of his actor friends. But that was a gangster noir, a genre that Cagney was very familiar with. It appears there was no such rewrite here.

The story is presented as a circular narrative. We start with a scene of Hollywood luminaries gathering in the famous Stage 28 Phantom of the Opera Theatre, which was built in 1924 for the classic film starring Lon Chaney. We’re led to believe that this is a memorial event to commemorate the actor upon his death in 1930. The Hollywood studios did indeed observe a two-minute silence to coincide with his funeral, but there was no such event. But here, Irving Thalberg (Robert Evans), the MGM studio boss and a friend of Chaney, takes to the stage and his eulogy introduces the film. He describes Chaney’s talent of illuminating “certain dark corners of the human spirit,” and praises him for showing to the world “the souls of those people who were born different from the rest.”

These lines inform our reading of the entire film as we flashback to see the young Lon Chaney (Jerry Hartleben) as an eight-year-old trotting home with a bloodied nose. He’s met with silence by his parents. This is anything but stern stony silence, though—actually quite the opposite. They are both deaf-mutes and communicate using sign language. His mother (Celia Lovsky) is sympathetic and supportive.

Having a mum and dad who were both different was enough to attract the attention of the neighbourhood bullies but, apparently, Lon used to pretend he was deaf also, in solidarity with his parents. These early scenes show us that his formidable acting prowess in silent movies stems from growing up using sign-language and mime to communicate. It’s also an insight into why he was later attracted to playing those people who were born different, how he let their humanity shine through and elicited sympathy for ‘monsters’.

It was the 25th film for director Joseph Pevney, who would later go on to direct many key episodes of classic Star Trek (1966-69), including my favourite “The Devil in the Dark”. Incidentally, he would work with Celia Lovsky again when she played Vulcan matriarch T’Pau in the episode “Amok Time”. He directs Man of a Thousand Faces in a solid and workmanlike way but doesn’t set it apart from many films of the ’50s.

The monochrome cinematography is beautifully handled by Russell Metty, a favourite collaborator of Douglas Sirk, who helped define melodrama. He had also worked with Orson Welles on The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), The Stranger (1946), and again on Touch of Evil (1958). He infamously fell-out with Stanley Kubrick whilst filming Spartacus (1960) but, nonetheless, the film won him an Academy Awards for ‘Cinematography’.

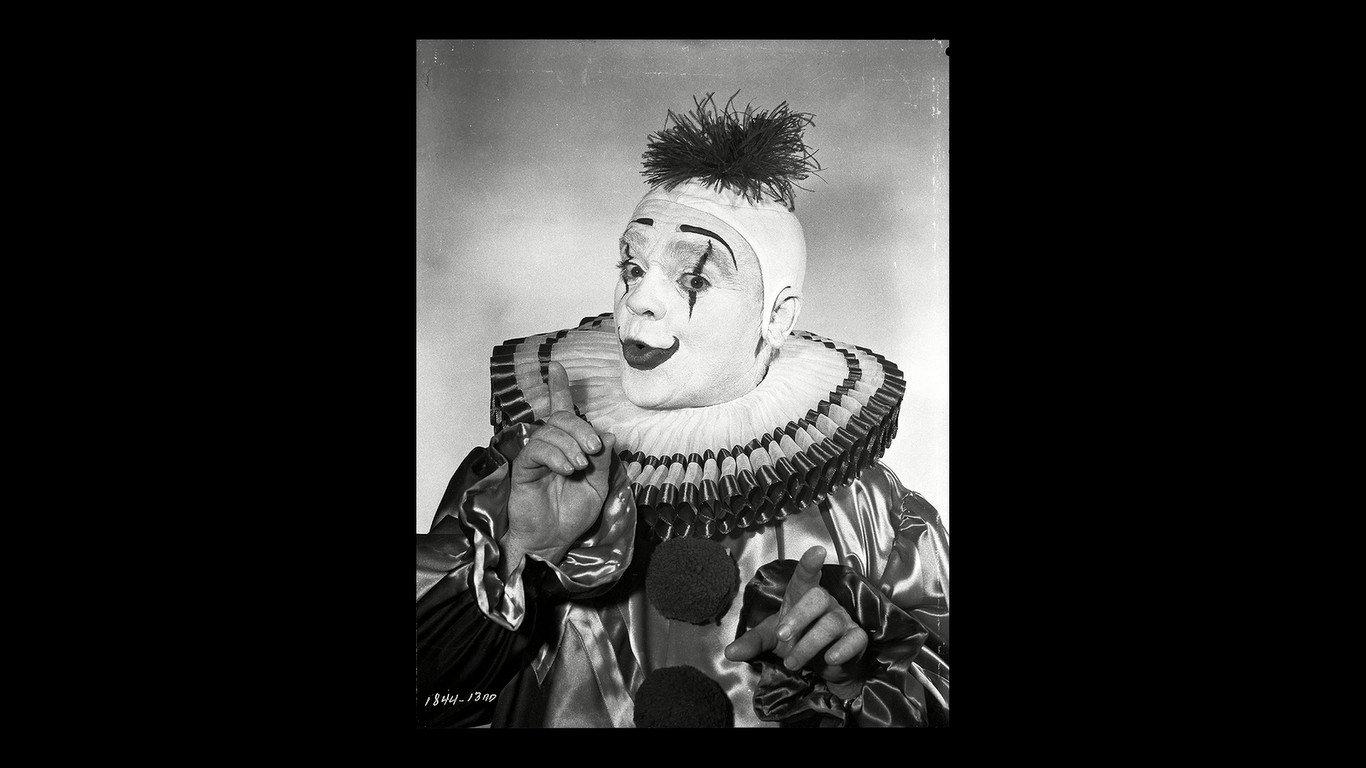

We meet the adult Lon Chaney (James Cagney) backstage at a run-down theatre with a visually interesting flooded basement. Cleva (Dorothy Malone) is rushing to her stage call when she falls into said floodwater and is unable to perform her act with Lon. He’s forced to perform solo, improvising a comedy dance routine with a mannequin instead of a real woman.

I use the term ‘comedy’ rather loosely here! I’m sure it’s quite authentic for what passed as side-splitting humour in the Vaudeville of the early-1900s but, to a modern eye… well, it’s just awkward and hard to push past. It does give Cagney a chance to showcase his talent for physical theatre, however. Just like Chaney, he started out on the Vaudeville stage.

Dorothy Malone was fresh from her Oscar-winning role for Douglas Sirk in the highly respected Written on the Wind (1956), and she brings with her the same melodramatic method playing Lon Chaney’s first wife Cleva. Back in the dressing room, she tells Lon that she’s pregnant and he seems delighted, yet Cagney manages to weave in a sense of unease. We soon learn this is because he feels he now has to introduce his young bride to his folks, and it seems he had neglected to let on about them both being deaf.

The earlier substitution of a shop-dummy instead of his wife is quite telling. The gender representations fall foul of the era’s accepted norms, but bear in mind the film is set decades earlier. Cleva wants a career, she came from poor beginnings and had to fend for herself until she met Chaney and they were married a few days later. In this version, the palpable tension between Cleva and the Chaney family stems solely from her prejudice of their disability that manifests as a full-blown phobia. She’s crippled by her dread that their baby might be born deaf or, as she puts it, “a dumb thing!”

Apparently, Chaney’s parents didn’t fully approve of her either, suspecting that the young girl, 17 when they married, was manipulating the older Lon, still only in his mid-twenties. They suspected her of using him as a way of getting away from her former life. This seems to be borne out later when she insists on finding her own job and starts to accept significant gifts from wealthy patrons and accompanying them on dates. She clearly found rich older men attractive! But when Chaney was eventually older and much, much richer, he didn’t want her back in his, or their son’s, life. It’s also nice to see James’s real-life sister Jeanne Cagney playing Lon’s grown-up sister Carrie, and this lends a realism to the screen time they briefly share.

The female leads are all fine, as far as their roles take them, but they’re women of the 1950s playing women from the 1910s and ’20s. Dorothy Malone gives a great multi-layered portrayal of the troubled Cleva, but there’s still little to latch onto or sympathise with. Her cry for help when she confronts Lon onstage and drinks the mercuric chloride does change the audience’s view of her. Surely, she’s in need of help, some sort of redemption, perhaps some unconditional love. She doesn’t seem to get any of those things.

Of course, we aren’t too far out of the Victorian era at this point in the story. Back then it didn’t take much for women to be dismissed as hysterical. For most of the film, she comes across as the villain, her ableism is underlined as a vile and evil trait. Which, of course, it is. In the interest of clarity, at a time when disability was widely misunderstood, the script makes it crystal clear, with no subtlety whatsoever, that her attitude is bad. I’m sure this is a genuine attempt to address social issues and injustices but again seems rather ham-fisted these days.

The other woman in Chaney’s life is Hazel (Jane Greer), a chorus girl whom Lon had met in his theatre days and later marries. Their marriage finally convinces the judges that there is now a stable home for his son to return to. Jane Greer’s performance is equally multi-layered, but Hazel’s a fairly standard 1950s version of the ideal woman who happily steps into housewife mode. When the men are out fishing, she waits patiently to return with their catch so she can cook dinner for them.

It’s a film of its time, trying hard to be faithful to the attitudes and sentiments of an earlier era whilst reinforcing those of its own. The script holds together but lacks the finesse to match the performances. The facts are bent and stretched to serve a clearer narrative. The chronology is anachronistic but, for the most part, remains within an acceptable dramatic license. The story’s tinged with a sadness throughout and the only real pleasure lies in those performances, particularly that of James Cagney who brings his great range to this portrayal, a hot favourite to win an Oscar but didn’t even get nominated.

For me, things pick up at the mid-point, when Chaney moves to L.A and gets involved with the newfangled movie business and eventually ‘makes it big’. I really enjoyed all the references to the classic movies of Lon Chaney, especially the re-enactments of truly iconic scenes from The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925). However, Cagney’s prosthetic masks are nowhere near as effectively chilling as Chaney’s transformations were.

Famously, Lon Chaney suffered for his art, using greasepaint, wires, and animal bones that allowed him full use of expression. Top make-up artists including Rick Baker (winner of the first Academy Award for ‘Best Makeup’, in 1981, for An American Werewolf in London), Dick Smith, and Tom Savini have all said it was Lon Chaney that first sparked their interest as youngsters.

I’m a fan of James Cagney and he’s great as Chaney, but I’m an even bigger fan of the real Lon Chaney and believe his Phantom of the Opera was possibly the best performance of the silent era. Man of a Thousand Faces does a fair job of telling his story, deferring to a poetic interpretation rather than the literal. But really, if you’re interested in Lon Chaney, then you’d be better off seeking out his surviving films, after all, the man himself once said: “between pictures, there is no Lon Chaney.”

director: Joseph Pevney.

writers: R. Wright Campbell, Ivan Goff, Ben Roberts & Ralph Wheelwright.

starring: James Cagney, Dorothy Malone, Jane Greer & Jim Backus.