THE LADY EVE (1941)

A trio of classy card sharks targets the socially awkward heir to brewery millions for his money, until one of them falls in love with him.

A trio of classy card sharks targets the socially awkward heir to brewery millions for his money, until one of them falls in love with him.

The Lady Eve is, indubitably, a classic comedy. It has one of Hollywood’s great writer-directors at the helm and two of its top stars in the lead roles. Trouble is, it’s just a tad too clever for its own good, with an almost novelistic approach that has a similar vibe to something Oscar Wilde might’ve penned. The dialogue is often as sharp-witted and its themes risqué, though intelligent enough to closely skirt what was permissible in its day without once crossing a line.

If you’re a fan of the screwball genre and already know the film, you won’t need any convincing. If this is new territory, you’re in for a treat so long as there’s some understanding of the context: it’s old, it’s dated, and it’s black-and-white. At the same time, its sensibilities are surprisingly modern. What was funny then still is today, and this new 4K digital restoration from Criterion beautifully retains authentic audio-visual textures, which only complements the frisson of nostalgia.

The themes of The Lady Eve are being set out during the fully-animated opening titles, credited to Leon Schlesinger, producer for both Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies, though it’s been suggested that Tex Avery also lent a hand. A happy snake weaves its way between the credits and assembles a set of three apples bearing the main title. The serpent. The apple. Eve. These Biblical motifs then weave their way through the entire film.

Charles Pike (Henry Fonda) is a naïve, socially awkward millionaire who’s more comfortable in the company of reptiles than socialites. We join him as he ends his year-long expedition up the Amazon River, boarding a little tugboat with his brash valet, Muggsy (William Demarest), and a new friend called Emma, a snake.

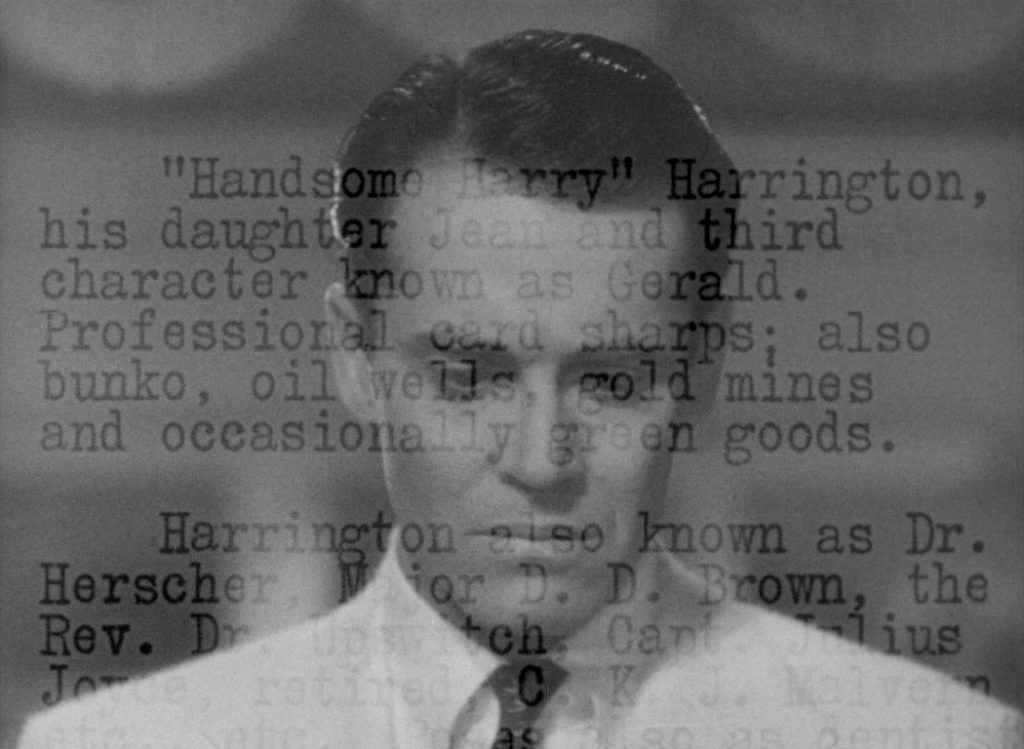

He attracts the attention of the passengers on an opulent ocean liner as it makes an unscheduled stop to allow him to board. Surely, he must be some sort of VIP. As he climbs the ladder, a part-eaten apple falls from above and bounces off his pith helmet. It’s been dropped by Jean Harrington (Barbara Stanwyck), a ruse to make him look up so she and her father, ‘The Colonel’ (Charles Coburn), can get a good look at his face. Why? Because their valet (Melville Cooper) has just checked the passenger roster and reports that Pike is the heir to an ale brewing fortune and a perfect mark for their card-shark confidence trickery.

And so, in a matter of minutes, the principal players are rapidly introduced and their characters outlined with beautifully crafted dialogue. This was a stellar cast for the time and, whilst they’re all well cast and competent, Barbara Stanwyck is the real star here.

Stanwyck turns in a wonderful, multi-layered performance throughout and, by the climax, she’s delivered a subtle and complex triple role. It’s a showcase of talent that ensured her a wide variety of parts over a six-decade career, taking in romantic leads, strong matriarchs in Westerns, and more classic comedies. She’d already received an Academy Award nomination for her role in Stella Dallas (1937) and, by the time she played the definitive femme fatale in Double Indemnity (1944), Stanwyck wasn’t only the most in-demand actress, but the highest-paid woman in America.

Here, she’s reunited with Henry Fonda, after they worked together in the noir spoof The Mad Miss Manton (1938). To cash-in on their shared success in The Lady Eve, they would be immediately paired once more in romantic leads for You Belong to Me (1941) another rom-com.

Fonda wasn’t well known for his comedy and his Charles Pike (or ‘Hopsie’ as Jean nicknames him) is little more than Stanwyck’s straight man. Having said that, he does it so well, demonstrating great restraint and a remarkable talent for physical acting. He masters the deadpan timing of the script and makes his many ‘pratfalls’, which could easily have reduced the cleverness to slapstick silliness, seem natural and even endearing.

The first half is pleasantly watchable and the super-slick dialogue, laced with double-entendre, is enough of a hook to keep you onboard through the first half. There’s also an edge of desperation and decadence in the party atmosphere pervading the decks of the ship. It’s not made explicit, but all these rich folks are en route back to America because the war in Europe was escalating and international waters were becoming unsafe. Their happy-go-lucky lifestyles were increasingly under threat, but no one knew, until later that year, the Pearl Harbour attack would bring the US into WWII.

Just when you think you have the measure of the movie, though, it abruptly shifts gear into a genuinely, laugh-out-loud comedy that tempers its sweetness with some delicious emotional torture. We have a change in supporting cast with the introduction of Hopsie’s father (Eugene Pallette) and one of the Colonel’s old conman pals, Sir Alfred (Eric Blore), and Barbara Stanwyck metamorphosis into Lady Eve. In effect, the first act is simply the set-up for the second, and by then, just like poor Hopsie, we’ve fallen for it.

Falling is a recurring motif. Not only the falling apple right at the start that reminds us of the original fall—of Adam and Eve—which complicated gendered interactions ever since and made rom-coms possible! People also fall for falsehoods, and they physically fall over. Characters in the film fall in, and out of, love. They fall for confidence tricks and false identities. Things fall on them. And we, the audience fall for them, too. As well as falling for the gags and the grand illusion of cinema.

Director Preston Sturges is one of the great larger-than-life figures from the Golden Age of Hollywood and is regarded as the country’s first auteur. He’d been writing plays for Broadway since the late-1920s and transitioned to screenwriting in the early-1930s. He was incredibly prolific and earned a reputation for churning out scripts with superb dialogue that were ready to shoot on delivery, saving the studios the time and expense of rewrites.

He used this leverage to wangle his first stint in the director’s chair for his own comedy, The Great McGinty (1940), selling the script for just $10 on the condition he was at the helm and took a cut of the profits. The film was a box office hit and won him an Oscar for ‘Best Original Screenplay’. This cunning deal, and the resulting success, established a template that would soon be exploited by other Hollywood writer-directors like Billy Wilder and John Huston.

Apparently, Sturges achieved the naturalistic flow of dialogue by refusing to actually write it down. It’s said he sometimes stood and played with a yo-yo as his dictated, to preserve the cadence of spontaneous speech and maintain a rhythm. I think his approach is most clearly evidenced in The Lady Eve, only his third movie as the director and still regarded as one of the best comedies of interwar Hollywood. Ironically, he’d based this story on an unproduced 19-page outline, ‘Two Bad Hats’, written by little known playwright Monkton Hoffe, that Paramount Pictures owned the rights for.

The screwball comedy genre dominated Hollywood during the latter half of the ’30s when audiences wanted escapism, but also needed to address the inequalities they saw all around them during the Great Depression. The main screwball signifiers include a battle of the sexes, usually involving a challenge to masculinity and an almost feminist portrayal of strong women. There’s nearly always some sort of role-reversal and an element of masquerade or mistaken identity. For the time, they tended to be a little edgy, having become popular in the pre-Hays Code era. They often tackled serious, even profound themes, such as differentiating our given and chosen identity, and how those identities related to the increasingly blatant class divide and outmoded gender roles.

I’m a sucker for a good screwball comedy (which are surprisingly few and far between) and thoroughly enjoyed The Lady Eve. The genre template had been laid-out by Frank Capra with It Happened One Night (1934) and consolidated by Gregory La Cava’s My Man Godfrey (1936), which, incidentally, also featured Eugene Pallette in an almost identical role to the long-suffering patriarch he plays in The Lady Eve. My favourite entry into the genre would be Ball of Fire (1941), written by Billy Wilder, directed by Howard Hawkes, and once again starring Barbara Stanwyck as Sugarpuss O’Shea—an even more vivacious variation of her part(s) in The Lady Eve.

USA | 1941 | 94 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Preston Sturges.

writer: Preston Sturges (based on ‘Two Bad Hats’ by Monckton Hoffe).

starring: Barbara Stanwyck, Henry Fonda, Charles Coburn, Eugene Pallette, William Demarest, Eric Blore, Melville Cooper, Janet Beecher, Martha O’Driscoll & Robert Greig.