KILL BILL: THE WHOLE BLOODY AFFAIR (2006)

After waking from a four-year coma, a former assassin wreaks vengeance on the hit squad who betrayed her.

After waking from a four-year coma, a former assassin wreaks vengeance on the hit squad who betrayed her.

You don’t need me to tell you that pop culture nostalgia has gotten out of hand in the last 10-15 years. I recently watched a review of the Steven Spielberg film Ready Player One (2018), itself based on the 2011 Ernest Cline novel of the same name, and the reviewer made the point that a parody song about its cringeworthy nostalgia-baiting (“Rejected Theme Song from READY PLAYER ONE”; sample lyrics: “Remember Akira? That’s from Japan. Remember Gallagher, and Mrs. Pac-Man?”) ended up having more cultural impact, despite the film’s huge success in the Chinese market. The plot of the movie and book dealt with Cline’s nerdish interests as a Gen X-er who never let go of his childhood, with a facile message tacked on at the end about how you should sometimes put down the GameBoy and, like, socialise with women.

Quentin Tarantino—born on the cusp between Boomers and Gen X-ers—is arguably not hugely dissimilar from Cline; his work also reflects pop cultural obsessions that were never put away with the proverbial childish things. The difference is that, whereas with Cline and the culture of the 2010s, nostalgia degenerated into empty pandering, Tarantino’s gift since the start of his career has been the elevation of homage and pastiche to a unique vision. Kill Bill is Ready Player One—the protagonist’s personal quest built around constant references to a prior era’s pop culture—except written and directed by a filmmaking genius. (Ready Player One had Spielberg, to be fair, though hardly in his prime.)

Tarantino arguably helped to usher in our current age of nostalgia, just as his early works in the pulp crime genre influenced pretenders to his throne for years. (There’s an amusing bit in On Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, a 2023 book by Claire Dederer about the art-versus-artist debate, where she discusses a period in the 1990s of film critics having to see dozens of films that copied Tarantino’s violence-and-cocky-dialogue model.)

Now we have The Whole Bloody Affair. Kill Bill tells the story of the Bride (Uma Thurman), conspicuously unnamed for most of the film (when characters say her name before Tarantino wishes to reveal it, it’s bleeped like a swear on TV). Four years before waking up from a coma, the Bride and her entire wedding party were gunned down by the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad, of which she was once a member. Her codename there was ‘Black Mamba’, and her jobs were overseen by Bill (David Carradine), a man whose name precedes him in the criminal underworld. Now the Bride is determined to take revenge on her former colleagues and, at last, her boss. Her confrontations with each mark the structure of the film, which utilises Tarantino’s early technique of non-linear narrative; after the more straightforwardly plotted Jackie Brown (1997), Kill Bill arguably provides a bridge between Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994) and the writer-director’s later, more linear work.

Tarantino also employs chapter headings and various digressions, à la the “McDonalds in France” conversation from Pulp Fiction, though done in the context of what is basically a comic-book movie as made by a filmmaking genius. When he was first making Kill Bill, he intended it to be a single film, but was told to release it in volumes by former producer and (as we now know) sex offender Harvey Weinstein. Even with his crimes aside, Weinstein was already known as a Philistine. Tarantino recalled in the wake of the producer’s exposure that he had had to remonstrate with him for loudly talking shop at a première.

Weinstein infamously put pressure on directors to shorten their work, perhaps anticipating the Philistine element of the moviegoing public. Things in that respect have hardly gotten better now, even if, in terms of length, the opposite is now pursued—to keep the audience’s eyeballs chained to streaming services; studios still always have the lowest common denominator in mind.

Who knows what a story as unique as Kill Bill‘s would have looked like in 2003 if its author were not such a big name? With absolute studio control, it might have just been an incoherent 90-minute mess with some memorable fight scenes, as opposed to the operatic masterpiece of pastiche and homage it became. Kill Bill is similar to Star Wars (1977) in how it takes the populist fiction of the creator’s youth and fashions a mythic narrative from its raw materials.

Tarantino said of its construction and the pressure put on him to remove the digressions:

“I’m talking about scenes that are some of the best scenes in the movie, but in this hurdling pace where you’re trying to tell only one story, that would have been the stuff that would have had to go. But to me, that’s kind of what the movie was, are these little detours and these little grace notes.”

Watching The Whole Bloody Affair, he’s obviously right. It’s well known that, in Volume 1, there’s an extended anime sequence describing the early life and career of O-Ren Ishii (Lucy Liu), the Bride’s first target, though the second to be shown, since the confrontation in the House of Blue Leaves involves the first half’s largest, longest set-pieces.

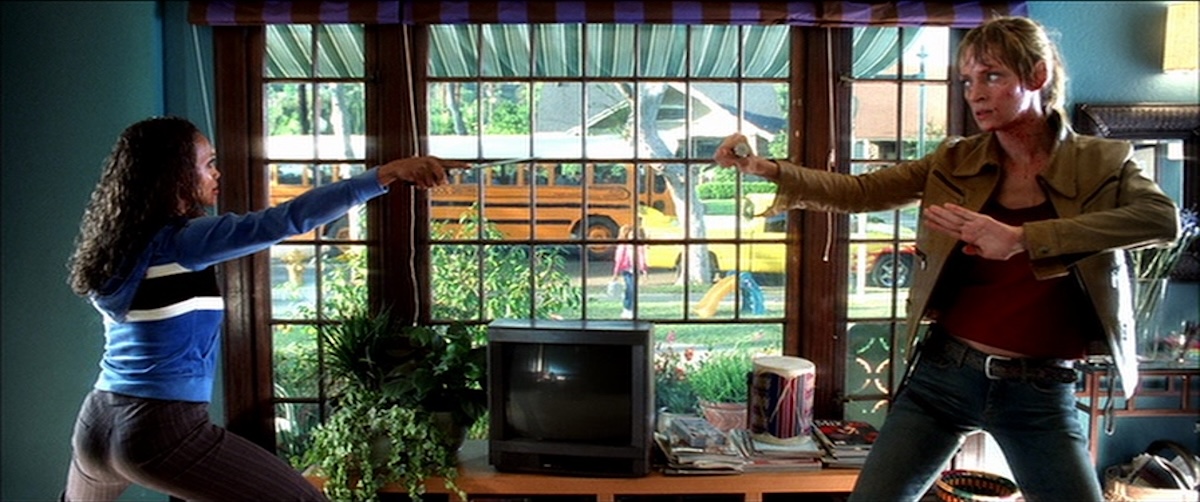

(By contrast, the Bride’s fight with Vivica A. Fox’s character Vernita Green is confined to a storybook suburban home, better suited to the film’s opening salvo. Could Tarantino have simply made Vernita the first target chronologically as well? Maybe, but that would have made the structure less interesting. We essentially start Chapter One in media res—following the black-and-white prologue—then go back to explain how the Bride reached that point.)

The anime sequence with O-Ren was of significant length in the original Volume 1 release. In The Whole Bloody Affair, it approaches 20 minutes, an extra 10 added to include O-Ren’s revenge against the chief lieutenant of the yakuza boss who murdered her parents. It occurred to me while watching this latest stitched-together version of Kill Bill that O-Ren gets more backstory than any other character in the film, including Bill, and let alone the Bride. We know something about Bill’s childhood from the exposition in Volume 2. The most that we get for the Bride, however, is a shot indicating that she went to a traditional elementary school, which is only there to finally confirm what her actual name is.

This is despite O-Ren, by contrast, being a fairly minor character so far as the overall plot is concerned. She’s the ‘Final Boss’ of Volume 1, sure. But if we strip the film back to its base elements, her function is really to provide an oriental flavour, setting, and tropes to the scene, allowing an entryway to the martial arts genre. Unlike the other members of the Deadly Vipers, she does not share much either thematically or personally with the Bride. She’s not a mother like Vernita, a blonde rival like Elle Driver (a gloriously vampish Daryl Hannah), nor even a potential sibling-in-law like Bud (Michael Madsen in scuzzy and saturnine mode), Bill’s brother.

I have seen people complain that the anime sequence is too long, though it’s not for me. It contains certain tropes of anime that I am not fond of, like its weird relationship with rape, misogyny, and paedophilia. As I recall, there was speculation, at the time that Volume 1 came out, that part of the reason the sequence was animated was to avoid censorship. Which makes sense, given how O-Ren lures the yakuza boss. The added material with the chief lieutenant certainly affects the pacing of Volume 1 even more than it already did, but it makes sense in the context of both volumes each comprising a film’s worth of material, with O-Ren as the prime antagonist of the first.

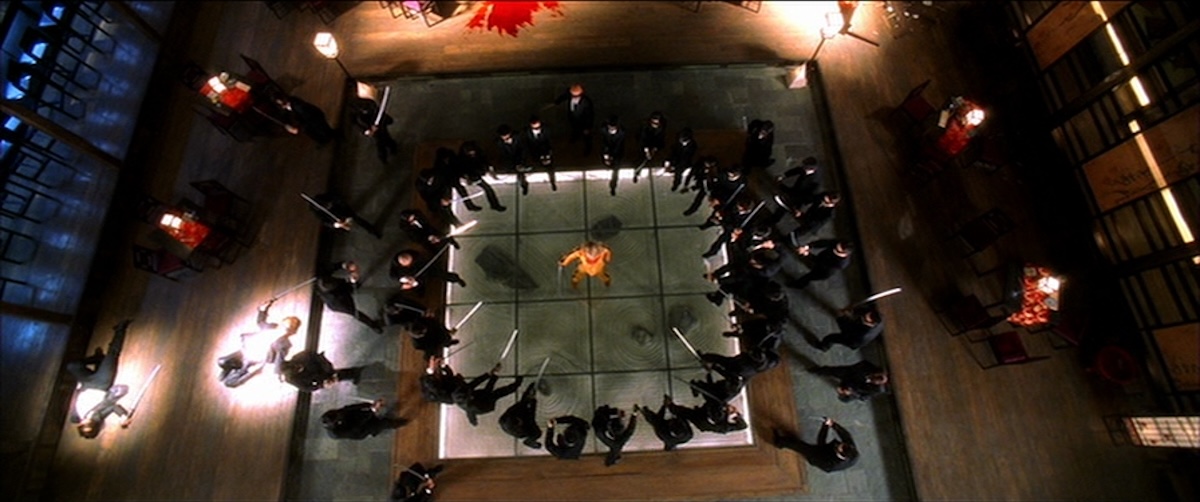

Regardless, as a whole, Kill Bill is one of my favourite films. It’s in the Top 10, and now I can say that about Kill Bill—instead of specifying Volume 2. The consensus, at least amongst younger viewers in the early-2000s, was that Volume 1 was the preferred half, because it was mostly non-stop action and culminated in the insane fight scene in The House of Blue Leaves, the restaurant to which O-Ren and her colleagues retire for what they hope will be a little R&R.

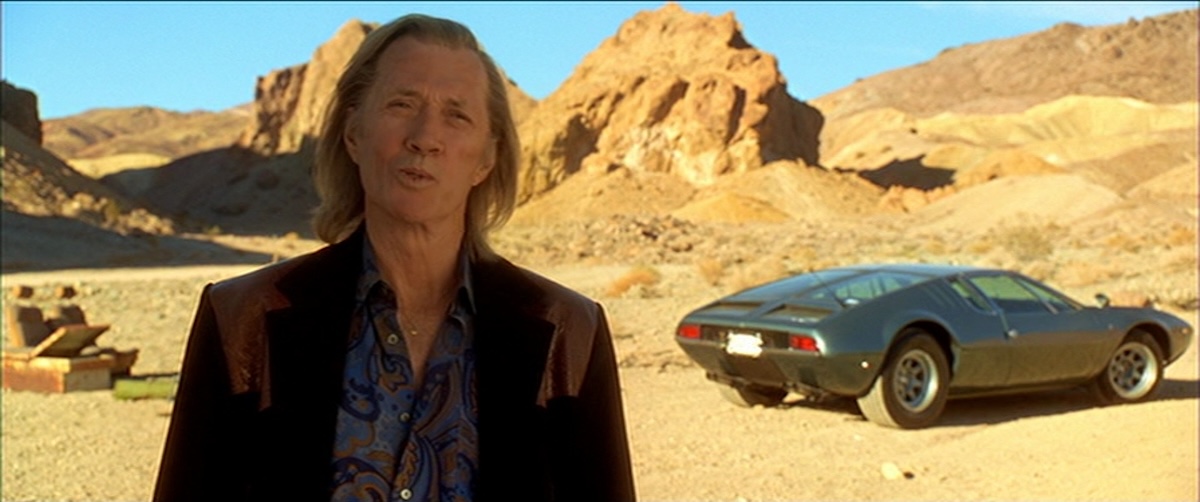

For me, however, the best was always Volume 2 because that’s the one with all the plot, and I liked the strange and tragic love story that unfolded between its leads. From the tale of Pai-Mei told beside a desert fire pit, to that startling and beautiful last confrontation, between Bill and the Bride that was never really his, as much as he needed her to be.

The acting is uniformly excellent. I don’t think that there’s a single bad performance in the piece, although Thurman and Carradine are, of course, the standouts. Perhaps just by dint of being a woman and a female character, Thurman and the Bride are allowed to be vulnerable instead of merely superhuman.

Her driving motivation is revenge, although this changes somewhat when she learns the secret kept from her until she bursts in on Bill in his hacienda. Revealing that the real truth all along was about the choices that she and Bill made regarding not just themselves, but those for whom they would bear responsibility. When the Bride fights Vernita in Volume 1, she learns that Vernita has a daughter. By the end of the film, we know what family means to the Bride, and that while she had to avenge herself against Vernita, her enemy’s motherhood weighed upon her.

Thurman and Carradine have wonderful chemistry. One of their best scenes shows them approaching one another on the porch of the chapel in El Paso, where the tragedy occurs. Tarantino has been mocked for his foot fetish, yet here the close-ups of their feet aren’t disposable and make perfect sense; the two predators move towards one another, tentatively, testing the ground between them. The female predator hopes that the male can restrain his baser impulses, for both their sakes, and that his finer self will rise above the purely animal. More fool her.

Aspects of the film continue to trouble me. I have always been uneasy about a scene towards the end of Volume 2, where the Bride goes to a South American pimp, Esteban (played by Michael Parks, in a dual role alongside the Texas sheriff who investigates the slaughtered wedding party in El Paso), for information about where she can find Bill.

The character is an ethnic archetype, and might qualify as a species of brownface given Parks’ tan and affectations. He opens and closes his eyes with the lazy predation of a lizard, and talks out of the side of his mouth a lot. It’s an excellent performance, I should say, so much so that I don’t think I realised until seeing The Whole Bloody Affair that it was Michael Parks.

What I find disturbing, though, is a moment that comes next. In a line that still gets something of a laugh—or did out of my audience—he remarks that Bill shot the Bride in the head, then says that he would have been much nicer. To illustrate this point, he summons a woman whose face has been cut to create an artificial hare-lip, and hands her a kerchief with which to soothe it.

Who is this woman, and what is her story? These aren’t questions that Tarantino cares to answer. They exist as a flourish, like Esteban himself, and many of the detours that for Tarantino were what the film was always about.

However, there is an argument to be made that despite its depiction of “strong” women, the film puts its female characters on a par with males as fighters and killers to justify the misogynistic, patriarchal world that they ultimately exist within. Esteban is not really judged by the film, not negatively. And the Bride’s opinion of him is oddly restrained; how does she feel about the woman whose face has been cut? Does she wonder if she, too, was pregnant? If that is why she “betrayed” Esteban, the same reason why the Bride fled Bill?

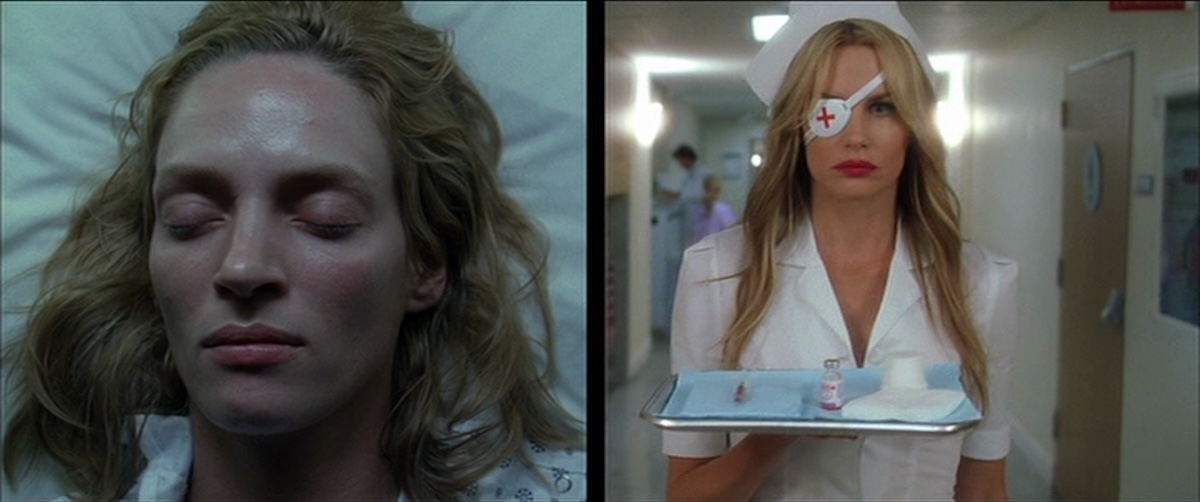

Again, just flourishes. Like O-Ren Ishii and her experiences with paedophilia. It’s a testament to Tarantino’s skill with pastiche and homage that the themes implied around gender-based violence don’t sink the film by any means, although they do remain a shadow on the lens, so to speak. Misogyny is Kill Bill’s implicit theme, in the way that racism was the explicit theme of Tarantino’s Django Unchained (2012). You also see the world’s patriarchal bent in how the orderly Buck manages to sell comatose women to be raped, despite obviously being a creep, and there being no great covertness to his scheme. No man who drives a bright yellow pick-up with ‘Pussy Wagon’ decaled on its rear is a Machiavelli, I would argue.

You can find misogyny present in the dialogue throughout the film, dealing as it does, you could say, with rough and most certainly unreconstructed men. Perhaps especially Volume 2, set mostly in either America or Pai Mei’s (Gordon Liu) house of pain. Pai Mei, the Bride’s Chinese tutor in the martial arts, is described by Bill as hating Americans and women. Yet he will see in his female pupil the seeds of worthiness. His tutelage is one of the best parts of a film made up of little except best parts, walking the line between comic and majestic via Tarantino’s style, homaging as well as parodying the tropes of martial arts cod-mysticism. (I especially like how he flicks his long white beard to underscore emotions.)

Another theme of The Whole Bloody Affair is ageing and trying to live a normal life. Of the Deadly Vipers, only O-Ren has really carried on in a similar career, as an underworld crime boss. The rest lead scattered and typically mundane lives. Vernita is a Pasadena homemaker, while Bud, as we see at length in the first act of Volume 2, leads a lonely and humiliating existence as a bouncer at a strip club where nobody respects him. It’s perhaps telling that O-Ren is the only one who is not American; she was able to retreat to her own world, as her colleagues were left in the wake of their crimes in El Paso to establish “regular” trajectories, and become citizens. The best monologue in the film is when Bill, using superhero comics as an allegory, discusses how hard it’s to run from who you are.

Kill Bill could be seen primarily as a triumph of music and editing. Its soundtrack and how the shots relate to one another are arguably where the storytelling lies, more than in specific dialogue and plot, excellent as those are. Tarantino is not pointing his camera at a story to capture the latter on film; he’s creating the story with the camera. Some great films feel like stage plays; Glengarry Glen Ross (1992), which was actually based on a play, My Dinner with Andre (1981), and a lot of the work of Woody Allen come to mind. Kill Bill isn’t one of these. In fact, it’s almost the antithesis. There are monologues and dialogue exchanges that you could put on a stage, and obviously, a martial arts film would need adaptation to work in live performance, but as a visceral experience, the majority is in the needle drops, close-ups, and so on.

The logic of the plot is completely ridiculous in any real-world sense. One of my favourite logical howlers is when the Bride kills two people in a hospital and retreats to the backseat of one of their cars, on which she spends thirteen hours (as stated by the film), regaining mobility in her feet and legs. I will leave aside the logistics of killing two people, noisily and bloody, before wheeling yourself to a car park undetected. How long would it take the police—presumably called in the more than half a day that elapsed—to investigate the hospital car park and check the relevant vehicle?

Yet this does not matter because the hyper-stylisation takes us into a world of unreality that still feels internally consistent. Sometimes Tarantino calls attention to artificiality, such as in a shot of a plane approaching a skyline that references the models-and-matte-paintings look of old B-movies. And also the themes of the film support its immersiveness. It typically annoys me in genre fiction when the bad guys have the hero in their clutches but don’t deliver the coup de grâce because then the story would have to end. (Think James Bond villains.)

Another logical howler: in Volume 1, Elle’s due to kill the Bride when she’s called by Bill and given a lecture on why she shouldn’t do that, literally as she’s about to pull the proverbial trigger. Thank goodness he didn’t pause to file his nails before dialling. There are a few moments like this. However, for me, they’re all justified by a single line from the Bride: “When fortune smiles on something as violent and ugly as revenge, it seems proof like no other that not only does God exist, you’re doing His will.”

Why does the Bride keep surviving? Why don’t her enemies seize their opportunities when they are presented to them on a silver platter? Because fortune has smiled on the Bride, and the God of her world is working His will through her.

USA | 2006 (2003, 2004; ORIGINAL RELEASES) | 275 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR • BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH • JAPANESE • MANDARIN • FRENCH • CANTONESE • SPANISH

writer & director: Quentin Tarantino.

starring: Uma Thurman, Lucy Liu, Vivica A. Fox, Daryl Hannah, Michael Madsen, Sonny Chiba, Julie Dreyfus, Chiaki Kuriyama, Gordon Liu, Michael Parks & David Carradine.