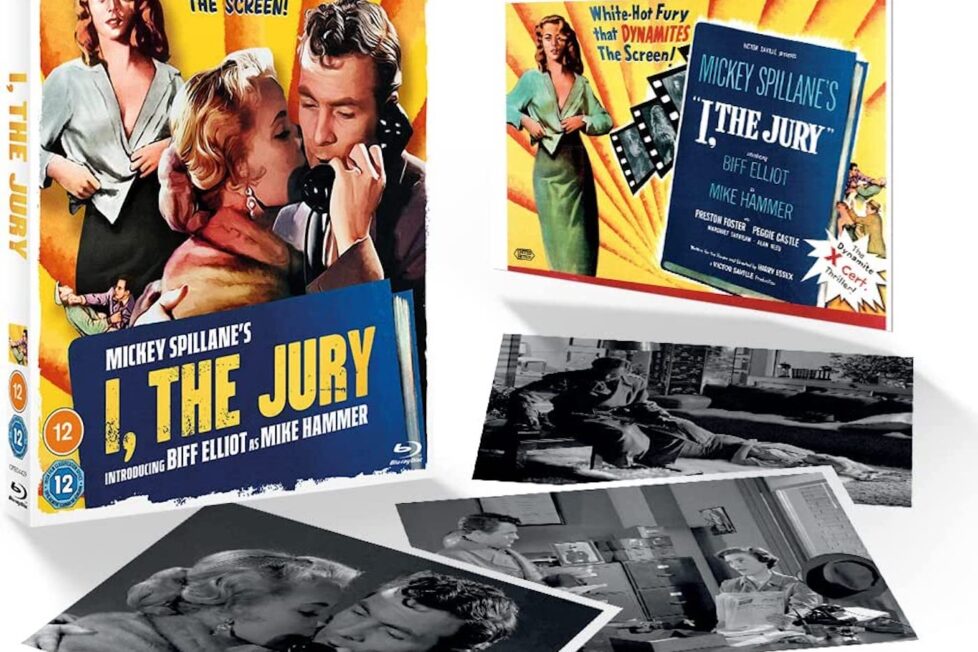

I, THE JURY (1953)

Detective Mike Hammer is faced with multiple suspects in his search for the killer of an old friend...

Detective Mike Hammer is faced with multiple suspects in his search for the killer of an old friend...

A chicken drumstick held aloft, a backscratcher coquettishly waved about by a potential femme fatale… some of the odder moments of I, the Jury are attributable to its origins as a 3D movie, filmed using the Dunning process during that brief period when black-and-white and 3D coexisted.

At other times the shots presumably intended to benefit from a third dimension will strike the modern, 2D audience as less weird and more impactful—a .45 slug in a palm, a photo in a View Master-like device that shows a woman pointing a gun.

And indeed, in this movie where the photography and direction are far superior to the writing and acting, a 3D opportunity must have been the prompt for the terrific opening sequence. Behind the credits a gunshot victim (Robert Swanger) crawls toward the camera, reaching out desperately; we eventually see he’s grasping for his own holster, hung on a chair that’s just come into view, and then an unseen hand belonging to someone implicitly located right next to the audience pulls the chair back out of reach, sealing his fate.

Much of film noir cinematographer John Alton’s work on I, the Jury continues to be thrilling as the film progresses, but unfortunately the same cam’t be said for the rest of it. The plot is convoluted and profoundly uninteresting, while the characters are lacking in depth and their motivations are often contrived or unclear. Even the exact nature of the principal villain’s criminal enterprise is vague (perhaps because the guardians of the Hays Code urged that it be changed from drug smuggling to…. well, something jewel-theft-related-ish).

The biggest problem with the movie, however, and one identified by many critics, is Biff Elliot in the lead role as Mike Hammer. Wooden in his voiceovers as well as onscreen, completely lacking in gravitas or any internal conflict, he comes across as a petulant, stupid bully. By the end of the movie, even his smirk is annoying.

It’s true that novelist Mickey Spillane’s Hammer was more rough-and-ready than Sam Spade, say, and it would have been unfaithful to the writer’s creation to portray him as a sophisticated, morally troubled sleuth. Many contemporary critics of the books made complaints about the character similar to those I’m making about Elliot’s performance, after all. But even if the general tenor of the performance is justifiable, the film also seems to be inviting us to empathise or identify with Hammer—yet at the same time, Elliot’s unlikeability makes it difficult to do so, while his lack of charisma prevents him from being appealingly unorthodox.

Though he had a long career as a character actor in movies and TV after I, the Jury, Elliot’s contract to portray Hammer in subsequent movies went nowhere and the three films featuring the detective that appeared soon after (1995’s Kiss Me Deadly, 1957’s My Gun is Quick, and 1963’s The Girl Hunters) featured three different actors in the role: Ralph Meeker, Robert Bray, and finally Spillane himself, who publicly criticised Elliot’s earlier acting.

It’s a pity because there are some decent if unspectacular performances in other roles—notably Peggie Castle as the psychoanalyst Charlotte, Margaret Sheridan as Hammer’s assistant Velda (another strong and intelligent woman), and, in more vulnerable ways, Frances Osborne as the distraught fiancée of the man killed in the opening sequence, and Mary Anderson as Eileen the dance instructor who almost certainly offers more than rhumba tuition in the private room where she teaches. (It was doubtless the Hays Code again which led I, the Jury to stop short of explicitly identifying the dance school as a brothel or drug den in disguise.) Among the male cast, the great noir stalwart Elisha Cook Jr. appears in an uncredited role as a boxer in a Santa Claus outfit.

None of them is given enough presence to rescue the film from Elliot, however, or from the screenplay by director Harry Essex (who around the same time co-wrote possibly the most famous of all 3D features, 1954’s Creature From the Black Lagoon). Essex’s script does the job of getting through the incessant twists and revelations efficiently enough, but perhaps too efficiently: it can seem hasty and more concerned with conveying plot points rather than giving the characters believable dialogue (maybe inevitable when there’s so much plot compressed into 87 minutes) and the language feels bare and functional, rather than picturesquely hard-boiled.

After Jack Williams (Swanger) is murdered at his New York home in that opening sequence, his old military pal Hammer (Elliot)—now a private detective—starts looking into the case. The police, led by Captain Chambers (Preston Foster), aren’t entirely pleased by his meddling but also see an opportunity to use him by placing a story in a city newspaper. A reporter has already called Hammer a “one-man police department”, after all, and they figure that if the media plays up his involvement in the investigation the killer might be tempted to target Hammer next, and thus be drawn into the open. The story duly appears under the headline I, the Jury.

Hammer, meanwhile, goes through suspects one at a time—many of the individuals introduced by Christmas card images to make up for the absence of seasonal street scenes—and comes to focus on the crime bigwig Kalecki (Alan Reed, later the voice of Fred Flintstone). He also seeks the help of and inevitably falls in love with the psychoanalyst Charlotte (Castle), but for much of the movie Kalecki and his art-student friend Hal Kines (Bob Cunningham) remain the most likely candidates. There are some hints of a gay relationship between them (Kines is referred to as Kalecki’s “pal and playmate”), much as between The Maltese Falcon’s Gutman and Wilmer (the latter played by Elisha Cook Jr.), but again we have the Code to thank for this going no further than a frisson.

Of course, the obvious suspects do not usually turn out to be the guilty parties in movies like this. And, of course, there are more bodies and narrow escapes for Hammer himself before it’s all over.

Such interest as I, the Jury has, however, does not come from this pretty routine and certainly over-frantic plot. Essex’s direction (unlike his screenplay) is replete with pleasing little touches—a plaintive dog at a vet’s, Hammer switching on a record as he leaves Eileen’s, a woman locking a door and Hammer promptly unlocking it again, all while they passionately kiss—but it is the full-on noir photography by Alton that really makes the film watchable. There is a real sense of depth even when seeing the movie in 2D, and a bird’s-eye shot of Hammer walking through the deserted streets by night is just one of many in I, the Jury that captures the tone of classic noir perfectly.

The Bradbury building in downtown Los Angeles, standing in for Hammer’s office, provides an architecturally rich backdrop for several scenes, and the always versatile Franz Waxman, fresh from double Academy Award wins, helps things along with a varied score including an effective jazz passage. (Although Waxman could and frequently did write perfectly well in the European Romantic idioms favoured by Hollywood at the time, one of his most acclaimed scores just a few years later—for 1956’s Crime in the Streets—would fully embrace jazz.)

I, the Jury is ultimately fatally harmed by Elliot’s hamfisted performance, and if Essex’s screenplay doesn’t actively damage the movie to the same extent it does it no favours either. As a whole, the film is a dud, but it does have some partially redeeming performances, displays some directorial imagination at times, and is beautifully shot—meaning that even if it can’t be recommended for broad entertainment value, it’s worth the impeccable restoration on this Blu-ray, and that alone will be of some interest to fans of noir. Those coming at it from a detective-fiction background will also relish the excellent commentary by Max Allan Collins.

USA | 1953 | 87 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Harry Essex.

writer: Harry Essex (based on the novel by Mickey Spillane).

starring: Biff Elliot, Preston Foster, Peggie Castle, Margaret Sheridan & Alan Reed.