HEARTS AND MINDS (1974)

Peter Davis's Academy Award-winning 1973 documentary is a passionate exposé of the war in Vietnam and its effects on ordinary people on both sides.

Peter Davis's Academy Award-winning 1973 documentary is a passionate exposé of the war in Vietnam and its effects on ordinary people on both sides.

While today’s streaming services and home video catalogues are full of World War II footage-based documentaries to meet the seemingly insatiable demand, we get much less of the Vietnam War on our screens. Ironic because, unlike its predecessor, it was a heavily televised conflict and the best-known visual representations (outside of fictionalised movies) are still photographs.

Much of the interest in Peter Davis’s Academy Award-winning 1974 documentary Hearts and Minds comes from simply witnessing the war and its effects: real things happening to real people, or being done by real people, in real places. 50 years later, with Vietnam now firmly classed as history rather than current affairs, that alone is valuable.

When the documentary was released, of course, audiences hardly needed reminding of its reality, and though Davis’s agenda is clearly anti-war he took a roundabout approach to expound it. Instead of packing the film with opponents of the US involvement in Indochina, he instead concentrated on those who had at least at some point supported it, or had taken part. (Here, some of the opponents are given more of a voice in the excellent outtakes section on Criterion’s Blu-ray.)

There is probably just enough explanation of the history, strategic concerns, and so on, to make it comprehensible to a novice in the 2020s, and aspects often overlooked today—such as the deep involvement of the US in Vietnam from the early01950s, long before troops were sent in large numbers—are brought home well. Even those who know a little about the war may be taken aback to learn that Ho Chi Minh, the North Vietnamese leader, expected the US to either not care about the country… or to come in on his side.

Davis presupposes some familiarity with the subject, however, and the film is more impressionistic than strictly chronological. This helped make it, at the time, as divisive as the war it covered. One interviewee, the presidential aide Walt Rostow, even managed to get distribution temporarily blocked, and there’s some validity in the criticism it can ignore other sides of the story. A tortured American ex-POW is presented as essentially a symbol of mindless patriotism, for example, yet the Viet Cong’s treatment of him is hardly mentioned, even while the American abuse of Vietnamese prisoners is laid bare.

Still, it’s not as if the official (pro-American and anti-Viet Cong) take on the war was unfamiliar in the early-1970s, so some corrective rhetoric can surely be excused. From today’s perspective, Hearts and Minds surely wouldn’t stand up as an objective factual history, but it’s not meant to be one; it’s ultimately not about political or military issues and more about American attitudes to the war, and the effects those had on individual people. There, history has found little to admire.

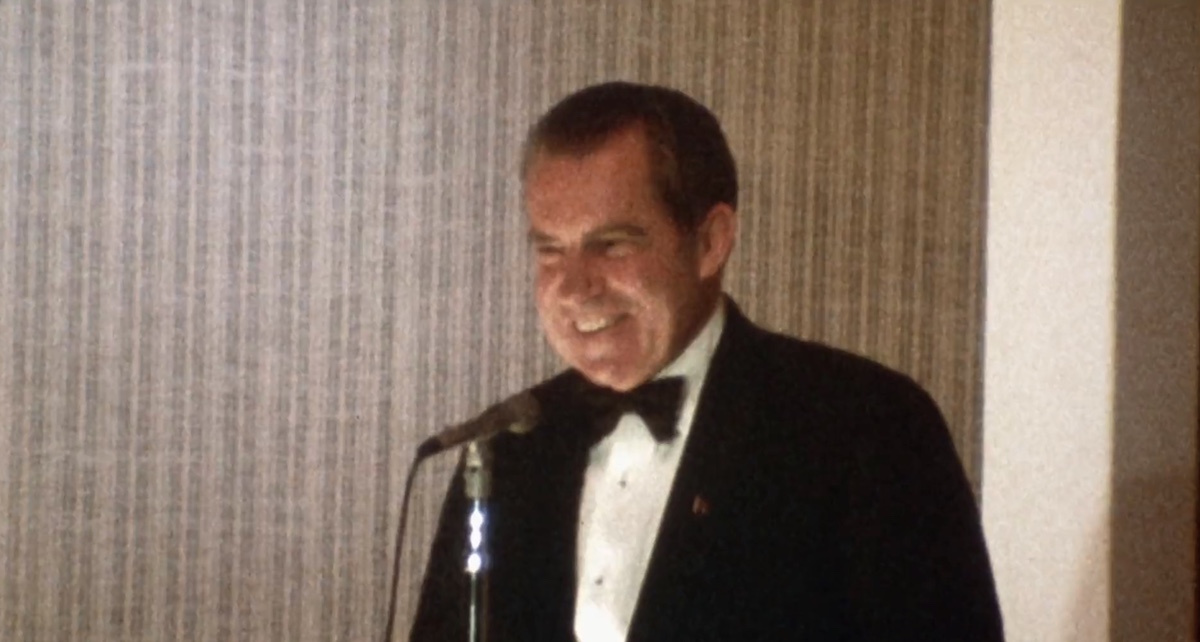

Davis mixes pre-existing footage with interviews very effectively. There’s all the relatively familiar material you might expect, like a montage of presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon speaking in succession, for example, and much coverage of American bombing raids (though none of the infantry combat). But, more importantly, there’s a great deal you wouldn’t expect…

While the film is far from dominated by people in positions of power, they do get some time. Clark Clifford, a former Secretary of Defense, is one who acknowledges US errors, but others, such as the notorious General William Westmoreland, commander in Vietnam from 1964 to 1968, are clearly not inclined to do so. Westmoreland’s calm observation that “the Oriental doesn’t put the same high price on life as does a Westerner” remains among the most shocking moments of the movie.

The emphasis, though, is on ordinary people. There is a long, silent shot of two elderly Vietnamese women who’ve lost everything; there’s a Vietnamese man whose daughters were out feeding the pigs when American B-52s dropped bombs that killed them. The pigs survived, as did one daughter’s shirt. “She will never wear the shirt again,” he says. “Throw the shirt in Nixon’s face.”

There is a factory turning out child-size coffins; there’s a young Vietnamese man being beaten, to the (added) soundtrack of “Johnny Get Your Gun”. But the Vietnamese in Hearts and Minds are not just the poor and the victimised: there are businessmen doing well out of the war, drinking at a Saigon country club; there are interviews with a former South Vietnamese cabinet minister and a former president.

Then there are two GIs exchanging banter with the Vietnamese prostitutes they’ve hired; there’s a deserter, Edward Sowders, giving testimony to Congress; there’s a vet trying on a prosthetic limb. There is, unexpectedly, even a Hollywood musical number reminiscent of Springtime for Hitler!

Back in the US, Davis also illustrates the breadth and depth of anti-communism (at least before public opinion turned against the war), both directly and by analogy. The cheerleaders at a high school football game in Ohio reach hysterical excitement in their support for the players; Davis cuts to Lyndon B. Johnson declaring “we are going to win.”

Flag-waving crowds and a brass band hail similarly greet the prisoner of war Lieutenant George Coker on his return to New Jersey in 1973 and we later see him on the lecture circuit, speaking to supportive crowds. At a White House dinner for ex-POWs, Bob Hope cracks a joke about his “captive audience”.

One of the most interesting interviewees is Daniel Ellsberg, who along with Anthony Russo (featured on the outtakes) leaked the Pentagon Papers to the media (and who later became a fascinating writer, notably in his 2018 book on nuclear deterrence, The Doomsday Machine). His upset and anger at the death of Robert Kennedy remind us that when the film was made these events were still new and raw; so does Davis’s trick, used more than once, of pulling back from a close-up to reveal that an American ex-serviceman has been permanently injured by Vietnam.

Hearts and Minds includes a brief sequence with Phan Thị Kim Phúc, the napalmed child in Nick Ut’s photo “The Terror of War”, possibly the most famous single image from the Vietnam conflict. But often in this film, it’s not what’s shown but what’s said which is most powerful. One of the most telling sequences—near the end of the documentary—features a reflective, articulate American ex-aviator, recalling how bombing Vietnam was for him just an “exercise of my technical expertise”, nothing to do with people on the ground.

But he doesn’t know how he’d react if his own kids were napalmed, he muses.

It’s moments like that stand out from Hearts and Minds. There’s insight from the high-level commentators (both pro and anti, and on the exceptionally good series of outtakes as well as in the film itself). There is some startling arrogance from the American establishment. But Davis’s greatest success is in bringing home the effect of conflict on many more innocent people, on both sides.

USA | 1974 | 112 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR • BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH • FRENCH • VIETNAMESE

director: Peter Davis.

editors: Lynzee Klingman & Susan Martin.