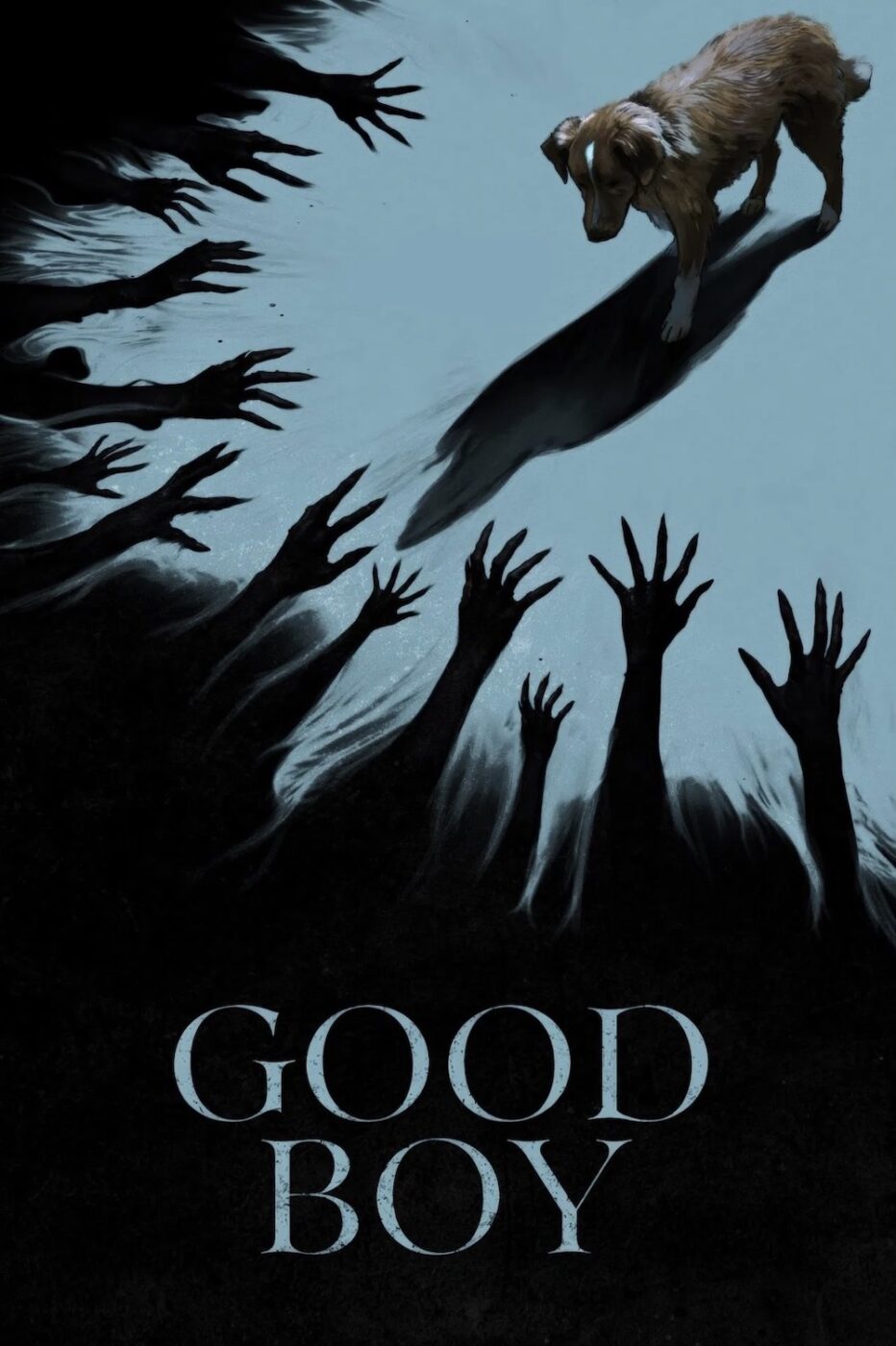

GOOD BOY (2025)

A loyal dog moves to a rural family home with his owner, only to discover supernatural forces lurking in the shadows.

A loyal dog moves to a rural family home with his owner, only to discover supernatural forces lurking in the shadows.

The hero of a horror movie isn’t always the easiest to root for. “Dumb protagonist syndrome” isn’t as common a tool for horror films as it once was, but there was a time when it was impossible to sit through one without someone in the theatre yelling at the screen in frustration. Luckily, the genre’s come a long way, and that’s certainly not the case in Good Boy. The premise is straightforward: a haunted house story told from a dog’s perspective. At a brisk 72 minutes, there isn’t a great amount of time to go into more detail. That runtime even includes a behind-the-scenes reel after the credits that explains the filming process.

The title character is played by Indy, a Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever and the real-life canine companion of director Ben Leonberg. In his feature film debut, the shoot took over 400 days, many of which were devoted to just a few seconds of screen time. That process isn’t noticeable to the audience, though. Each shot feels natural and authentic; a credit to the time devoted to the care put into each setup. The filmmakers capture Indy’s expressive brown eyes and edit the footage together to make it appear as if the dog has an uncanny knack for emotional timing. Without the help of voiceover or VFX trickery, the pooch’s range of emotions carries the entire film: suspicion, fear, love, protectiveness… even confusion.

Good Boy deploys a clever trick to avoid any possibility of falling victim to the dumb protagonist trope: cast a dog as the lead. Any bad choices will be ignored because a human will never hold a dog to their own standard. Instead, good decisions will be seen as impressive rather than expected. Unfortunately, the film isn’t devoid of all dumb characters.

Indy (also the dog’s name on screen) belongs to a human named Todd (Shane Jensen), who’s fallen ill. Not much is revealed about his sickness, and the audience is responsible for piecing together much of the plot on its own. But with the film shown from an animal’s POV, not understanding every detail all at once is to be expected, since the dog wouldn’t necessarily comprehend what’s going on around him. Just enough dialogue is given to allow viewers to figure out what’s happening, and that serves as a sufficient substitution for the keen intuition of a canine.

Todd and Indy’s backstory is provided by home videos going back to puppy days and bringing the audience up to the present day, when Todd’s being released from the hospital. From there, the duo end up at an old, abandoned farmhouse that Todd inherited from his grandfather (Larry Fessenden). However, from the moment they arrive, things feel wrong, and Indy quickly clues us into that. He hears sounds that shouldn’t be there. He stands at the top of the basement stairs, uncertain. He smells something’s not quite right…

For a low-budget horror film, the story is impressively carried by its technical filmmaking. The lighting plays a pivotal role. Clever camerawork is employed too, bringing Indy in and out of focus while something lurks in the shadows behind him. A carefully designed sound scheme is also used, tuning the audience into the things a dog might notice—the echo of a distant creak, a high-pitched whistle not audible to human ears, Indy sniffing for something foreign, the nervous rustle of fur against hardwood. The film has minimal dialogue, so its use of soundand atmosphere becomes deliberate and effective. The cinematography by Wade Grebnoel leans into muted browns and greys, evoking a sense of rural decay. The decision to shoot in natural light and often from knee-level height gives every room a claustrophobic quality. The editing mirrors a dog’s restless gaze—sharp cuts between close-ups and sudden, darting pans that create a sense of unpredictable awareness.

Through conversations with Todd’s sister, Vera (Arielle Friedman), we learn that the house is supposedly cursed. Much of the family was buried in a cemetery on the property, and Todd notes that many of them died at a young age, including their grandfather. While Todd tries to downplay his ever-worsening illness, Indy’s instincts—and, by extension, the audience’s—never settle.

Leonberg understands that the scariest part of this premise isn’t ghosts or jump scares. It’s powerlessness. Indy doesn’t understand what’s happening to his owner, nor can he warn him about the things he senses around the house. He can only watch, whimper, pace, and, in moments of eerie tension, stare off into corners at what Todd can’t see.

That ambiguity is one of the film’s strongest tools. Is Indy reacting to supernatural forces? Or is he responding to real-world cues of decay, illness, and isolation that Todd refuses to confront? Just as dogs are said to sense oncoming earthquakes or illness, Indy seems tuned into something bigger, but the film never spells it out. That choice allows Leonberg to maintain a sense of psychological unease while honouring the realism of the dog’s point of view.

Todd, for his part, is a hazy figure. Often shot from the torso down or obscured in shadow, he seems physically present but emotionally distant—not just to the audience, but to Indy. His illness is never explained, but its effects grow more pronounced. He watches old tapes of his grandfather, coughs sporadically, and grows increasingly erratic. He often makes decisions that the audience, as well as Indy, know are not the best. He ignores clear signs from both the house and from Indy. Is he dying? Losing his mind? Becoming possessed? It doesn’t matter to Indy, who stays by Todd’s side through every wheeze, every stumble, every strange encounter with neighbours who may or may not be what they seem. One wears full camouflage and moves like a wraith. Another resembles a mud-covered ghoul. Are they real? Manifestations? Dreams? The film refuses easy answers and is stronger for it.

To be clear, Good Boy doesn’t always maintain its momentum. The second act occasionally drags and some of the scares begin to repeat. Even with such a short runtime, exploring a canine nightmare is really only something that’s needed once. Everyone who has owned a dog has likely stirred them awake from a bad dream, so it’s interesting to get a chance to see inside one of those. Doing it a second time recalls a bad horror trope where a jump scare wakes the character from a dream. The house also gets a bit over-explored, and when a brief touch of CGI interrupts the climax, it’s more of a disruption than whatever the filmmakers are going for.

But even at its slowest ebb, the film’s commitment to tone and perspective never falters. And in its final 20 minutes, when Indy’s protectiveness boils into a race against time to save Todd, the film re-energises itself—poor CGI and all. It’s not just about ghosts any more, it’s about grief, and what it means to care for someone who’s slipping away.

When it’s firing on all cylinders, Good Boy doesn’t just make you scared of what’s in the dark. It makes you think about what your dog might see when they stare into it. And it reminds you how lucky we are to have animals who love us, even when they don’t understand us.

USA | 2025 | 72 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Ben Leonberg.

writers: Alex Cannon & Ben Leonberg.

starring: Indy, Shane Jensen, Arielle Friedman, Larry Fessenden & Stuart Rudin.