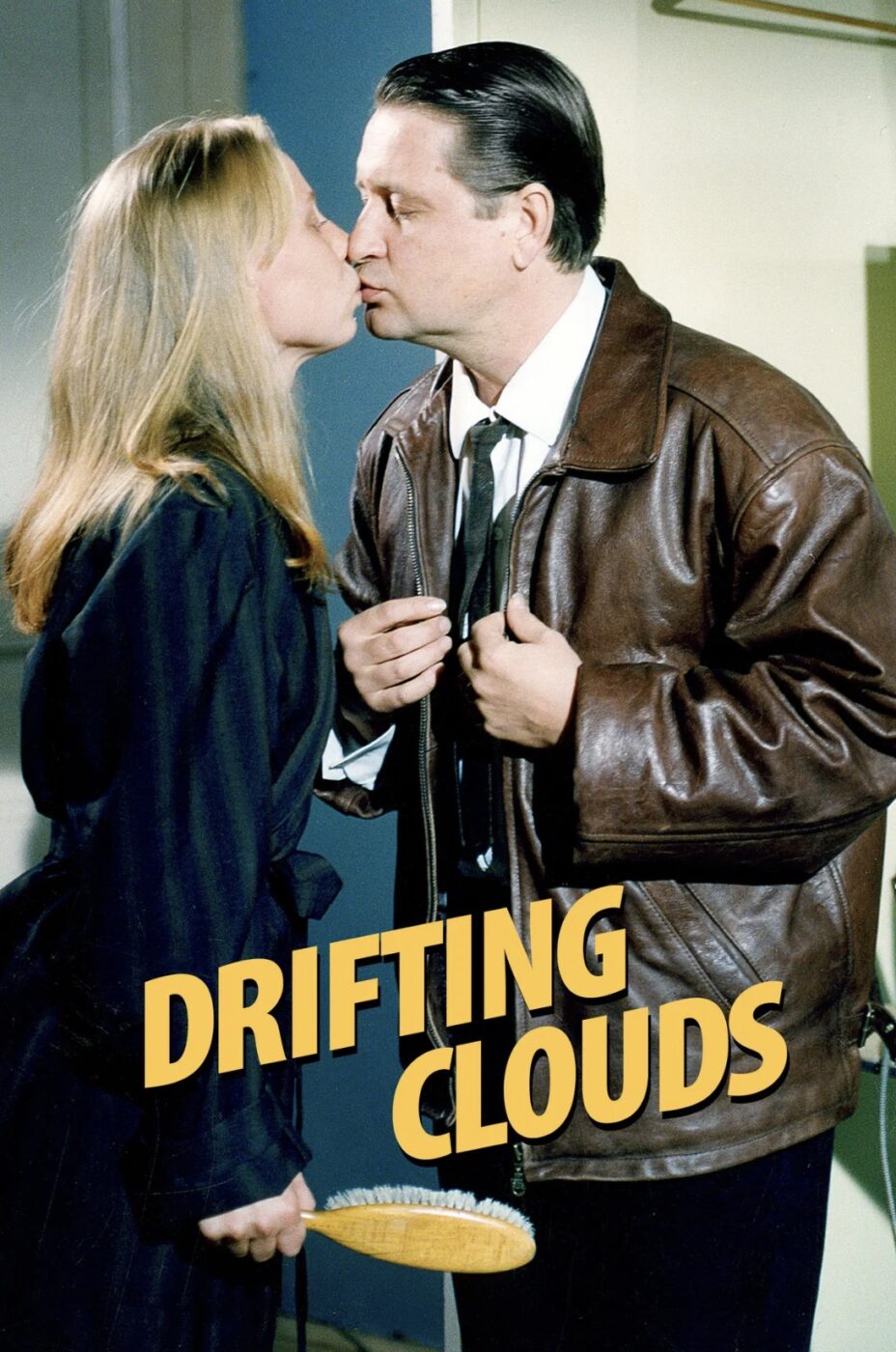

DRIFTING CLOUDS (1996)

The recession hits a couple in Helsinki.

The recession hits a couple in Helsinki.

Aki Kaurismäki may be one of the most repetitive filmmakers working today. His dry humour is an integral aspect of his filmography, leaking into a visual style that manages to be disaffected, poetic, and dreary all at once. His compositions are beautiful yet muted. His use of colour is second to none, but it serves to depict a world drained of life. His imagery evokes a relic lost in time, yet it isn’t saddled by sentimentality or nostalgia. And, of course, there’s a coldness to his films that one, whether rightly or wrongly, associates not only with the weather in his native Finland but also with the temperament of its people.

It’s easy to sum up his work by calling him the Scandinavian Wes Anderson, but that does both directors a disservice. Despite some similarities, Anderson’s oeuvre can be divided into distinct periods. Conversely, Kaurismäki doesn’t just like to retread old storytelling ground; he perfected his visual style long ago and has no interest in updating it.

It’s easy to see why. There’s an ageless bluntness to his humour that recalls the cinema of yesteryear, long before audiences ever heard a performer’s voice. Each of Kaurismäki’s actors is sharp enough to recognise the world they inhabit, offering deadpan deliveries that complement the director’s trademark wit. His sardonic punchlines are so visual that you wouldn’t even need dialogue for them to resonate; you could simply cut to an intertitle and back to the performer’s face, and the jokes would land perfectly.

That isn’t to say the Finnish director’s films are passionless. In his latest feature, the critically acclaimed, Academy Award-nominated Fallen Leaves (2023), romantic love may not be a solution to despair, but it helps heal the cracks formed by it. Joblessness was the primary struggle for that film’s protagonists—a recurring theme also explored in Drifting Clouds / Kauas pilvet karkaavat, where married couple Ilona (Kati Outinen) and Lauri (Kari Väänänen) struggle to make ends meet after losing their jobs.

The arbitrary nature of luck—or fate, if you feel compelled to give this cruel, farcical cycle meaning—isn’t without humour. In one scene, Lauri and his co-workers must draw cards to decide who will be fired. When he looks at his card, the world falls silent as the camera—usually so still in Kaurismäki’s work—pushes in on his face. Bang. He’s dead.

At least, that’s what must be on his mind as he watches the comfort of his immediate future crumble. The old-fashioned sets and production design of Drifting Clouds serve as a beautiful tribute to this cycle of change; the present becomes a relic before our eyes. In the restaurant where Ilona has been head waitress for years, a band plays a beautiful love song to close out her final night. She isn’t the only unlucky one; the restaurant has been sold to a chain, a modest business swallowed by an expanding corporation. What hope do ordinary working people have in an economic environment that bulldozes them with ease?

As Ilona listens to the music and watches her life hum to its moving tune, this bittersweet night suddenly appears as it has always been, though it couldn’t be appreciated before: a distant memory. It is so crisply realised through the film’s colour grading and disaffected camerawork that it might as well be an image on an old, forgotten postcard. Locked within these rigid stylistic and economic confines, even a simple zoom or close-up in Drifting Clouds transforms these scenes into heartfelt pleas for sympathy.

The “cuteness” of Kaurismäki’s droll style can be annoying; his characters often feel like cardboard cut-outs despite the focus on their problems. The fact that he recycles these dilemmas doesn’t help. His deadpan humour often lacks the element of surprise, much like a close-up of feet in a Tarantino film or excessive lens flare in a J.J Abrams picture. In this case, the familiar isn’t always comforting, especially when light experimentation would suit Kaurismäki’s style so well. Anderson is too wordy for silent films and, as suggested by his feature Asteroid City (2023), too invested in flaunting trickery to embrace a simpler style.

But imagine what Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin could’ve done in one of Kaurismäki’s films. At a time when silent film is practically non-existent, the director has a style tailor-made for the mould. It’s no wonder he praised them both as “the best of all time” in an interview, specifically noting the “pale silence of Keaton”. Instead, he continues to retread old ground, though Drifting Clouds holds an advantage over Fallen Leaves due to the nostalgic lens through which it views the couple’s former lives.

Joblessness creates a void, particularly for Ilona, while the absence of her specific vocation stings fiercely. The tragedy is twofold, elevating her from a glib construction to a real person. Even when her husband finds work, she remains unsatisfied, slowly falling to pieces at home. She misses him, but there’s a lurking jealousy there too, merging into a twin stream of paralysing helplessness.

Changing fortunes can be as swift as they are cruel. However, this film doesn’t give up on its characters, even if it seems the world has. They’re hemmed in by economic hardship and a deadpan style that dictates muted expressions. But beneath a layer of sullen dejectedness, those faces show signs of life through passion, self-pity, and tenderness. Outinen, who has starred in over half a dozen of Kaurismäki’s films, delivers an acting masterclass, as resilience and despair silently wage warfare across her features. If her face doesn’t betray this internal conflict, her eyes certainly speak volumes. Väänänen is also excellent, perhaps because the film plays to his strengths. He isn’t nearly as emotive as his co-star, but that works wonders.

He plays the man in the relationship, the one who must remain stoic at all costs. Drifting Clouds doesn’t adopt a chauvinistic outlook, but it isn’t foolish enough to deny how a middle-aged man might view his misfortune. The soundtrack and Väänänen’s physical presence tell this story better than words ever could. He puffs out his chest even as life fells his spirit. It’s one of those rare moments of kismet where a performer’s presumed limitations suit their role perfectly. If Lauri were to try to express himself, he would surely crumple into a mass of tears, sobs, and heaving shoulders. Matti Pellonpää, a frequent collaborator of Kaurismäki, was originally envisioned for the lead role, but his death from a heart attack in 1995 sent the project into freefall. The script was rewritten to focus on Ilona—a creative choice born of misfortune that, in retrospect, feels like the only way Drifting Clouds could’ve succeeded.

After Pellonpää’s death at just 44, it’s understandable why Kaurismäki considered scrapping the film entirely. As Drifting Clouds demonstrates, tragedy befalls us so easily. But just as essential to this bleak tale are the rays of hope lingering beneath the surface. They’re cruel reminders of better days, but they’re also the hands that reach out to us in moments of despair. They tilt our weary heads upwards, away from our dreary surroundings, until we are staring at the serene skyline of clouds drifting by.

FINLAND • GERMANY • FRANCE | 1996 | 96 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | FINNISH • SWEDISH • ENGLISH

writer & director: Aki Kaurismäki.

starring: Kati Outinen, Kari Väänänen, Elina Salo, Sakari Kuosmanen, Markku Peltola, Matti Onnismaa & Shelley Fisher.