DHEEPAN (2015)

A Sri Lankan Tamil warrior flees to France and ends up working as a caretaker outside Paris.

A Sri Lankan Tamil warrior flees to France and ends up working as a caretaker outside Paris.

For those acquainted with Jacques Audiard’s filmography (and not just the polarising, controversy-attracting 2024 musical Emilia Pérez), his Palme d’Or-winning film Dheepan is a recognisable blend of the director’s usual genres, tones, and styles. Unlikely couples who first earn audience’s sympathy, then their admiration, can be found in Read My Lips (2001) and Rust and Bone (2012). The former is a gritty crime drama, the latter a constantly evolving story whose resonance dims somewhat under the weight of its many facets. Dheepan, too, has great aspirations, even if it maintains a veneer of modesty throughout much of its runtime. It is actually its soundtrack that first gives away this story’s grandeur, with this delicate but heartfelt immigrant tale suddenly imbued with the glory of an epiphany being realised when composer Nicolas Jaar gets the opportunity to strive for beauty in his compositions.

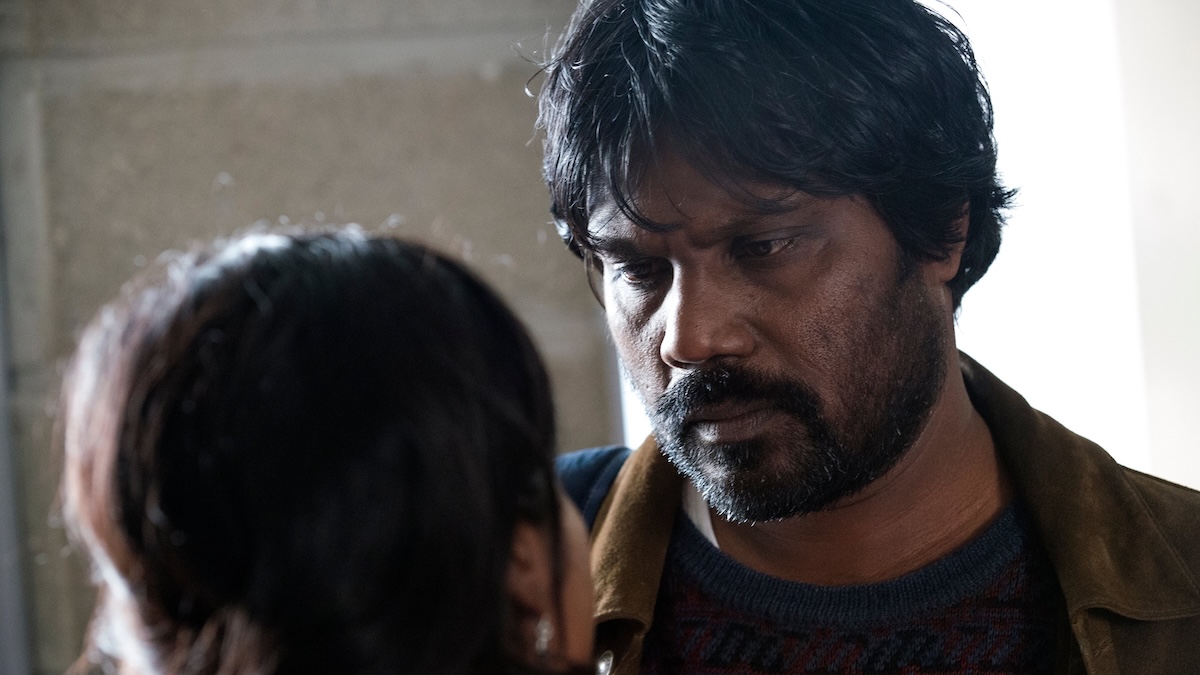

It’s an infrequent tactic, since this quality rarely presents itself in these characters’ lives. After Tamil Tiger soldier Dheepan Natarajan (Antonythasan Jesuthasan) sees his side lose in the Sri Lankan Civil War, he assumes the identity of a dead soldier and travels to France under this guise, accompanied by Yalini (Kalieaswari Srinivasan) and Illayaal (Claudine Vinasithamby), posing as his wife and daughter, respectively. This trio of strangers find themselves contending with an entirely new kind of warzone in a rough banlieue housing project, where the eponymous Dheepan works as a caretaker, Yalini cooks and cleans for drug lord Brahim’s (Vincent Rottiers) father, and Illayaal must reckon with the hostilities that abound at her new school. Everyday life is a battle for understanding and respect in a country that these characters are hopelessly adrift from, even as they slowly carve out a home—however precarious it may be—for themselves.

Dheepan treats this improvised family unit with so much tenderness that their trials and tribulations feel inextricably connected and urgent. Audiard has built an impressive career making us sympathise with criminals, whether they are a pair of young lovers committing one big heist to secure a better future, prizefighters earning their keep, or convicts forced to commit more crimes to survive in a hellish prison environment. Here he takes an even more overtly sympathetic approach to his characters, with this family unit forced to contend with violent gangsters while ensuring that they never become compromised by immorality. The trio hardly commit any crimes in the film, only doing so when they are pushed to such extremes that it is impossible not to also view their actions as a valid means of escaping dire circumstances.

Even when they have escaped the horrors of their native country, these characters still have to contend with unfair systems governing their immediate future, as well as the delicate balance on which their safety rests. The only respite from manipulation and fear is, ironically, a lack of understanding of all things French. Since the couple know next to nothing about French wages, or what to expect from life in Western Europe, they accept the meagre living conditions offered to them, even finding joy in them. Impressively, Audiard avoids the pitfall of treating these refugees as holier than thou, allowing them to retain their humanity even when he contorts this story to ensure the family unit is continually compromised by outside forces. It’s also worth emphasising that Dheepan would be an entirely different beast if Jaar was not helming the film’s score; his work is standard when exploring the everyday trials and tribulations of these characters, but soars when it conveys the love that blossoms between them.

Audiard slows life down in these tender moments, most of which take place in a squalid apartment. Even when this impromptu family are living in a run-down building occupied by thugs and and gangsters, they are still able to form something of a home together, exemplifying the beauty of the promise of a new life, the resilience of the human spirit, and one of the most earnest and loving depictions of the refugee / immigrant experience you will find in cinema in recent years.

The French director loves his gritty urban dramas, having made them a staple of his career before switching to more ambitious works (two of his most recent films, 2018’s The Sisters Brothers and Emilia Pérez, are English and Spanish language, respectively). At his worst, Audiard’s films become overcrowded, giving way to bloated affairs that turn their varied ingredients into a muddy soup of genres and tones. Each plot development or tonal rejigging hardly ever seems contrived on its own merits, but some of his films suffer when these lightly subversive elements keep occurring. By committing itself to this family and their turmoil in this housing development, Dheepan largely circumvents these narrative pitfalls. Instead, an equally frustrating flaw emerges: incuriosity.

When Yalini is tasked with looking after Brahim’s father Habib (Faouzi Bensaïdi), the smirks that are levelled by the man explaining her job description, and the interest that Brahim takes in this polite but withdrawn woman, suggests something more sinister at play. Then, when she engages in pleasant conversation with Brahim, who is relatively polite given his criminal ranking, there’s a suggestion of kinship between the pair. After smoking the end of a blunt left by the gangster and being spotted doing so, a giddy trepidation washes over Yalini.

Is she about to be taken advantage of in these exchanges, or would a sexual relationship between the two offer some much-needed relief to a woman forced to act as though she’s married to a man she hardly knows, all while raising a stranger’s child and questioning whether she even possesses a maternal instinct? Returning to the apartment that evening to see Dheepan and Illayaal practising French together, it is as if Yalini has stepped into the dependability of home life after a brief flirtation with danger at work. She might not technically be in a relationship, but it feels like cheating. She knows it, we know it, and Audiard knows that we know. He wisely chooses not to capitalise too much on this tension, leaving just enough room for chaos amidst a grounded narrative. It will all mean something in the end as the story builds to a crescendo, you are made to think. But it often doesn’t.

Few things are as depressing to witness as the ostracization of children, who are so often pushed around by other people and outside forces, lacking the agency, ability, or willpower to dictate their boundaries as they are being mercilessly prodded. Illayaal’s social exclusion at school is explored through one or two very brief scenes, which is enough to achieve their desired effect; when she attacks a classmate for harshly refusing her the opportunity to play with her peers, I could not help but silently cheer her on. When Yalini scolds the child for this behaviour in front of her teacher, the girl she attacked, and the girl’s mother, we watch this unfold from a distance. The shot is literally outside looking in, with Illayaal bowing her head in shame.

Should Yalini have slapped Yalini, incurring the teacher’s—or better yet, the other girl’s parent’s—pity and concern, the scene might have presented some thorny dilemmas to unpack. Instead, this instance of violence will occur later, in the privacy of their apartment, a moment of conflict near-instantaneously addressed and covered-up with a heavy-handed conversation that tells us about these characters instead of showing us anything real or urgent. Illayaal becomes something of a prop the longer she persists in this story, her troubles at school and inability to belong in this new environment largely forgotten about.

For a time Audiard loses track of where these characters are at emotionally. Escalating strife in the neighbourhood is artificially ramped up to add splashes of danger. The French director is clearly building up to something dramatic, but the malaise that settles over this story’s approach to its central characters is more pronounced than any of the plot developments. Growing lethargic, Audiard asks the audience to pity these poor souls even further, and the effect is contrived.

While it has already been mentioned here that Dheepan is quite predictable, the caveat to this statement is that it does not apply whatsoever to its intense third act. But not only is the action that unfurls surprisingly cheap-looking, the setup that precedes it is too contrived to take seriously. Part of that comes down to how little has been explored of Dheepan’s previous life as a soldier. Just like with Illayaal’s tough time at school, Dheepan’s connections to revolutionaries in Sri Lanka are introduced well but not capitalised on. Unlike the moving but overcrowded Rust and Bone, or the uneven, operatic mess that Emilia Pérez gradually devolved into, Dheepan represents the French director at his most undercooked.

Thankfully, there’s a feeling of authenticity in this feature that makes it easy to love at points. I cannot speak to the specifics of this world and how cleanly it maps onto reality, but Dheepan rarely condescends its characters. Jesuthasan has described this film as being roughly 50% autobiographical, and even lent insight to this director to make certain interactions more authentic. As for this leading actor, he, Srinivasan, and Vinasithamby provide performances just as tender and heartfelt as how Audiard and co-screenwriters Thomas Bidegain and Noé Debré treat these characters. Watching the trio attempt to carve out a space of healing for themselves amidst rocky circumstances is a beautiful, delicate thing. It is just a shame that so much of Dheepan’s plotting feels like an intriguing but unsatisfying first draft.

FRANCE | 2014 | 115 MINUTES | RATIO | COLOUR | TAMIL FRENCH ENGLISH

director: Jacques Audiard.

writers: Jacques Audiard, Thomas Bidegain & Noé Debré (story by Jacques Audiard and an uncredited Anthonythasan Jesuthasan).

starring: Antonythasan Jesuthasan, Kalieaswari Srinivasan, Claudine Vinasithamby, Vincent Rottiers, Faouzi Bensaïdi, Marc Zinga & Bass Dhem.